Understanding the political processes in the history of a particular nation is impossible without understanding their economic causes. Any society depends on the economy, which dictates its ever-changing rules. The civilizations of the distant past were no different from the modern world in this - Ancient Sumer was the cradle of statehood and culture of mankind, and therefore many aspects of his life are still relevant today.

Sumer - the land of the gods

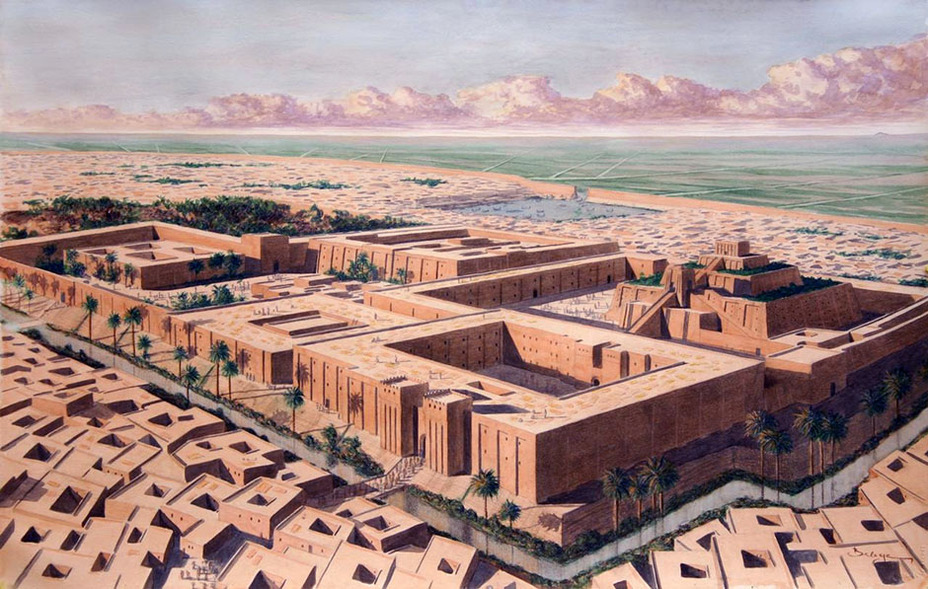

From the earliest period of formation and development of the Sumerian civilization at the beginning of the III millennium BC. e. the central place of the economic, political and cultural life of society was the temple. Each of the Sumerian communities (and then the Nome state formations) chose a patron deity for itself. If we consider the situation from the point of view of the Sumerians, then everything was exactly the opposite - the deity chose a place for himself where he wanted to live, and people had to take care of his house. Everything in the vicinity of this house, which we call the temple, belonged to a god or goddess: earth, water, animals, birds and, of course, people. All people, without exception, from the most inconspicuous member of the community to the leader, were only humble servants of the deity. The tasks of the servants were to build as many houses as possible for the divine lord or lady, fill them with beautiful things, and also praise the greatness of the god. For this, people could ask the heavenly patron for help in their affairs.

View of the temple complex in the city of Eredu. Archaeological reconstruction by the artist Balazs Balogh.

archeologyillustrated.com

Priests

In practice, this meant that all household work was led by priests. They also collected all the products produced in the storehouses of the temples, in order to then distribute it among the community members according to the value of this or that person. It is obvious that the value of a close servant of God (that is, a priest) is much higher than the value of an ordinary peasant or fisherman, which means that he should receive better food and clothing. "Close to God" were the children of the priests, who were supposed to inherit their parents' religious and economic functions, as well as privileges.

Most of their time, the "managers of the domain of god" and their assistants were engaged in organizing construction work, planning irrigation systems and accounting. A complex system of storage and distribution of grain, skins, wool, and tools of production gave rise to the need for strict fixation and a kind of accountability to the patron god. The simplest signs on clay tablets turned into a writing system in the form of the so-called cuneiform - the account was kept down to the grain.

Early documents record the relative equality of the distribution of products and things, but as new lands were developed, the population grew and its specialization deepened, the priests began to receive more and more rations. At a certain point, instead of being remunerated in kind for their work, the priests began to receive a land allotment, which the community members had to cultivate. Life became less and less fair, no one remembered the former equality.

View of the Sumerian city-state of Mari. Archaeological reconstruction by the artist Balazs Balogh.

View of the Sumerian city-state of Mari. Archaeological reconstruction by the artist Balazs Balogh.

archeologyillustrated.com

rulers

In the harsh climatic conditions of Sumer, it was extremely difficult for an individual or a small group of people to survive. On the other hand, organized collective labor provided not only guaranteed food, but also significant surpluses of agricultural products. These surpluses became not only the basis of civilization and progress, but also caused acute military and social conflicts. To force neighbors to pay tribute, it was necessary to fight. Armed conflicts became commonplace, and successful military leaders began to take most of the spoils for themselves. Even if the community did not wage wars of conquest, the threat of attack by enemies made people treat their war leaders in a special way, and they concentrated enough property and power in their hands to become important figures. During the war, the army of the city-state consisted of as many free men of the community as could be armed and fed - these men returned home as comrades in arms. Friendly ties between warriors served as the basis for the political influence of their leaders.

Politically, the Sumerian city-state was built in an unstable balance of power between the high priest with the title of ensi and the military leader with the title of lugal. Translated from the Sumerian language, “ensi” literally means “lord (or priest) of laying structures”, and “lugal” means “big (great) man (man)”. From an economic point of view, there were two households: the traditional community around the temple and the new palace around the lands appropriated by the Lugal dynasties. The power of the ensi, as a rule, did not go beyond the borders of their native nome, while the lugals claimed military superiority over several city-states or all of Sumer.

The economic interests of an individual nome never required extensive conquest. The Lugals, on the other hand, could maintain and increase their strength only by continuously fighting. The maintenance of a permanent professional core of the army and garrisons in the defeated cities was very expensive, so the lugals did not have enough of their own funds and the tribute received. The religious worldview and the strength of the Sumerian tradition were so strong that even such a “worldly” matter as war had a deep mythological justification. Since each of the city-states belongs to a god, then the gods also wage wars among themselves, and people are only an instrument of this ongoing conflict. Victory is possible only if a powerful heavenly patron wants to help the army of his city - and whose victory is the prey. Thus, a significant part of the war trophies settled in the temple economy. This strengthened the temples and priests and prevented the dynasties of generals from becoming the sole rulers of their nome. For the same reason, any conquests were short-lived, and the wars in Mesopotamia did not stop for centuries.

The Lugali did not want to put up with this state of affairs and tried to use their influence in order to arrange their relatives as high priests and through them gain access to the resources of the temples. Hereditary temple nobility in every way prevented this.

The river harbor of the Sumerian city of Ur. Archaeological reconstruction by the artist Balazs Balogh.

The river harbor of the Sumerian city of Ur. Archaeological reconstruction by the artist Balazs Balogh.

archeologyillustrated.com

community members

Under such a system of power, ordinary people (in Sumerian - “black-headed”) could rarely express their opinion. Usually the "will of the people" was expressed through spontaneous uprisings, usually following catastrophic military defeats. Another example of communal democracy is the election of a new high priest-ensi or tsar-lugal in the event of the suppression of the previous dynasty. In normal times, the community members were subjected to new taxes and duties, and their best representatives died in the war or sought their fortune in the lugal squad.

The most enterprising of the lugal's entourage took an example from their leader and did their best to get rich as quickly as possible. To do this, they used a banal, but incredibly effective abuse of power and position. Managing the royal estates, trading affairs or artisans, the courtiers appropriated the allowances and property of ordinary people. There were frequent cases when the townspeople were forced to sell their property to officials at a reduced price. Another way for a courtier to improve his position was to force free or dependent community members to work for him (this did not cancel the usual duties of a worker to the community and the temple). It was also possible to take advantage of hard times like war or natural disaster to lend the local community some grain until better times, and in case of non-payment of the debt and interest on it, take away part of the land.

The kings and their entourage took away the land from the temples. Of course, this could be formalized as a temporary concession in connection with the costs of service, but over time, such land began to be inherited. Thus, a whole class of landowners appeared who had their own allotments and passed them on to their descendants.

View of the center of the Sumerian city of Uruk. Archaeological reconstruction by the artist Balazs Balogh.

View of the center of the Sumerian city of Uruk. Archaeological reconstruction by the artist Balazs Balogh.

archeologyillustrated.com

Earth, water and people

A natural question arises why the main value in Sumer was precisely the land. The answer lies in the way it is processed. The truly valuable land was a strip several kilometers wide along the Tigris, Euphrates and their tributaries. To increase the area of these fertile lands, the Sumerians built an extensive network of drainage and irrigation canals. Taking into account the constant growth of the population, it was enough to own precious land, and there will be enough who want to feed from it. With such a system of management, the farmer could not simply leave to cultivate free lands outside the zone of natural and artificial irrigation, and, therefore, he was forced to endure the oppression of "big people". Forced stability to this society was given by the protective power of religion and fear of neighboring enemies, who could easily capture their native nome during political turmoil in it.

Stepped temple (ziggurat) in the city of Ur. Archaeological reconstruction by the artist Balazs Balogh.

Stepped temple (ziggurat) in the city of Ur. Archaeological reconstruction by the artist Balazs Balogh.

archeologyillustrated.com

From community to state

From the 28th century BC e., when the Sumerians began to build their statehood, and until the XXIV century BC. e. they have come a long way from a monolithic communal world with relative equality to a society torn apart by property stratification and social conflicts. The palace administration and the old temple nobility challenged each other for power, and no one wanted to give in this dispute. The rapidly impoverished disenfranchised population could only watch this fight.

Literature:

- Dyakonov I. M. Ways of history. M., 1994

- History of the Ancient East. Part I Mesopotamia. Ed. Dyakonova I. M. M., 1983

- Emelyanov V. V. Ancient Sumer. Essays on culture. Petersburg Oriental Studies, 2001

- Gulyaev V.I., Shumer. Babylon. Assyria: 5000 years of history. M.: Aletheya, 2004. ISBN 5–89321–112-X: 1000

- Weinberg IP Man in the culture of the ancient Near East. M.: Science. Main edition of oriental literature publishing house, 1986

- Mellart James. Ancient Civilizations of the Near East. "Science" M., 1982

- Diakonov I. M. Ancient Mesopotamia: Socio-economic History. Sandig Reprint Verlag, 1987

- Robert McAdams. An Interdisciplinary Overview of a Mesopotamian City and its Hinterland, 2008. ISSN 1540–8779.

- Samuel Noah Kramer. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press, 1971. ISBN-10: 0226452387 ISBN-13: 978–0226452388.

- Leonard Woolley. The Sumerians, 1965. ISBN-10: 1566196663 ISBN-13: 978–1566196666.

- In contact with 0

- Google+ 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0