At the end Russian-Swedish war 1808-1809 and the conclusion of peace with Sweden, Russian troops from the shores of Torneo and the Gulf of Bothnia moved to the banks of the Danube, where shortly before that the Russian-Turkish war flared up - a bloody battle, also inflamed by Napoleon back in 1806. Soon after the Austerlitz campaign, Napoleon entered into a close friendship with the Turkish Sultan Selim III and at the very beginning Prussian war gave orders to his ambassador in Constantinople, General Sebastiani, to arm the Porte against Russia in order to divert our forces from assisting Friedrich Wilhelm. The cunning Sebastiani managed to convince the Sultan that Russia intended to conquer Turkey. The Sultan began to show hostility towards us: contrary to the treaties, without the consent of our court, he replaced the Moldavian and Wallachian rulers loyal to us and locked the Dardanelles for Russian warships.

Russian-Turkish War 1806-1812. Map

The Russian-Turkish war became inevitable. Tsar Alexander I decided to warn the Turks and ordered General Michelson with an army of 80,000 to occupy Moldavia and Wallachia (end of 1806), meanwhile announce to the Sultan that Russia would not begin military operations if the Porte fulfilled the agreement, opened the Dardanelles and restored the rulers overthrown without any good reason . The British envoy to the Turkish court, Sir Arbuthnot, passionately supported the just demands of our court and called for help from the English squadron stationed near Tenedos: Admiral Duckworth with 12 ships and many fire ships entered the Dardanelles Strait (late January 1807), without harm passing the coastal fortifications, which were considered inaccessible, and suddenly appeared under the walls of Istanbul with a threat to destroy it if the Porte did not reconcile with the Russians. The frightened Turkish sofa was ready to give in; but the active Sebastiani encouraged him, advised him to extend the time with negotiations, meanwhile he armed the people, strengthened Constantinople, the Dardanelles, and in one week placed such batteries on the shores that Duckworth considered it best to retire to the Archipelago to save his squadron, which the Turks were already planning to exterminate in the Dardanelles Strait. The Porta announced a rupture to Russia.

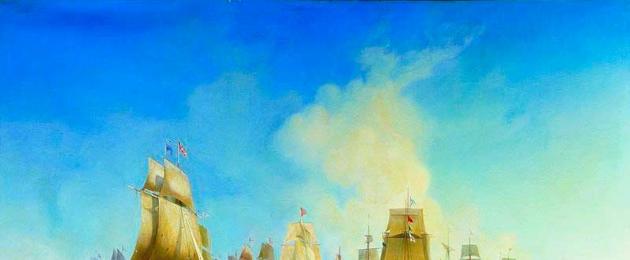

In the spring of 1807, the Russian-Turkish war began to boil at the same time on the Danube, beyond the Caucasus, in the Black Sea and in the Archipelago. Michelson established himself in Moldavia and Wallachia, capturing Bucharest; Gudovich defeated the Erzurum seraskir on the banks of the Arpachaya; admiral Senyavin won a brilliant victory over the Turkish fleet in the naval battle (June 1807) at Athos, reminding the Turks of the times of Chesme, and threatened to break through the Dardanelles Strait in order to terrify Constantinople itself, as the order was received to stop military operations against Turkey at sea and land, for conclusion of peace with the Porte through the mediation of France, on the basis of the Treaty of Tilsit concluded in the summer of 1807.

Russian-Turkish War 1806-1812. Naval battle of Athos, 1807. Painting by A. Bogolyubov, 1853

Mikhelson entered into negotiations with the Turkish commissioners, and in Slobodzeya agreed (August 1807) to suspend the Russian-Turkish war with an eight-month truce until a lasting peace was concluded; Meanwhile, Russian and Turkish troops had to clear Moldavia and Wallachia. The St. Petersburg cabinet did not approve the last article of the Slobodzeya Convention, foreseeing that the Turks would not leave Moldova alone, in which they were not mistaken: as soon as the Russian army moved away from the Danube bank, the enemy was in a hurry to occupy it. As a result, Field Marshal Prince Prozorovsky, appointed commander-in-chief after Mikhelson’s death, was ordered not to leave Moldova, however, refraining from breaking up.

The break in the Russian-Turkish war of 1806-1812 lasted more than a year and a half. Turkey, preoccupied with internal unrest, the uprising of the Serbs, the disobedience of the pashas, the riot of the Janissaries, willingly avoided fighting with Russia. Alexander I, preoccupied with the war with Sweden, wanted first of all to end the disputes in the north, so that he could act more decisively in the south; moreover, for him, on the basis of the Treaty of Tilsit, it was necessary to agree with Napoleon regarding the terms of peace with Turkey, and not before, as in personal their date in Erfurt(September 1808). This issue was resolved by the fact that Napoleon agreed not to oppose the expansion of Russia's borders on the banks of the Danube, to allow her to persuade her to that Port and refusing any mediation.

Upon returning from Erfurt, the Russian sovereign instructed Prince Prozorovsky to invite Turkish plenipotentiaries to Iasi to establish peaceful conditions. Congress opened in early 1809. The St. Petersburg cabinet demanded two conditions from Turkey: concessions to Moldavia and Wallachia and a break with England. The Porta refused both. The Russo-Turkish War resumed; however, until 1810 the war was carried out weakly and unsuccessfully. Prince Prozorovsky, an old general, burdened with illnesses, spent the whole summer besieging Zhurzhi and Brailov, could not take either fortress and allowed the Turks to establish themselves on the left bank of the Danube. After his death, Prince Bagration took over the main command over the army operating in the Russian-Turkish war. Fulfilling the orders of the court, he crossed the Danube on August 14, 1809 and besieged Silistria in September. The siege was unsuccessful. The vizier sent an army of thirty thousand to help the fortress, which was located several miles from the Russian camp, in a fortified camp. Bagration attacked her and was repulsed. The lack of food forced him to stop military operations beyond the Danube and return to Moldova.

In Bagration's place, a young general, but already famous for his brilliant exploits in Prussia and Sweden, Count Nikolai Mikhailovich Kamensky, was appointed commander-in-chief of the Moldavian army in 1810. With his appearance on the banks of the Danube, everything took on a different look: the Turks, who had hitherto disturbed Moldova itself, did not dare to show themselves in the field and hid in fortresses.

Nikolai Mikhailovich Kamensky, hero of the Russian-Turkish war of 1806-1812. Portrait by F. G. Weich, 1807-1811

Kamensky wanted to end the Russian-Turkish war one summer with a decisive blow, which was all the more painful for Russia since political affairs in the West were again taking on a menacing aspect. He transferred all his forces, up to 80 thousand, to Bulgaria and, at one time besieging Rushchuk, Silistria and Pazardzhik with separate corps, in June 1810 he himself with the main corps moved to the Balkans to take possession of the key of Turkey, the impregnable Shumla, where the vizier had locked himself up, with most of his troops. The campaign was brilliant: Silistria surrendered (May 30) after a short siege; Pazardzhik was taken by storm on May 22; the entire space from the Danube to the Balkans was cleared of enemies. They held out only in Shumla, Rushchuk and Varna. The vizier expressed a desire to once again stop the Russian-Turkish war with a truce; Kamensky demanded a decisive peace so that the Danube would be the border between both empires, and, without receiving consent, approached Shumla on June 10, 1810.

Twelve Russian battalions, after incredible efforts, climbed to the heights surrounding the Turkish fortress from the north, and there, after a two-day battle, they established themselves. All that remained was to reinforce them and raise the guns to the heights to defeat the city. The commander-in-chief, due to the lack of siege weapons, considered it best to besiege the fortress and stop the supply of food supplies in the hope of forcing the vizier to surrender by starvation. This measure, however, did not have the desired success. The Russian army, before the Turkish one, felt a lack of food and retreated to Rushchuk, where things were also unsuccessful. The siege work was carried out unskillfully; the garrison did not think about surrender.

Kamensky decided to take Rushchuk by storm. The army, inspired by the words of its beloved leader, cheerfully launched an attack on July 22, 1810, but was unable to climb the high walls, defended by the desperate courage of a large garrison; the Turks made a successful sortie and upset our columns. The army was in confusion. In vain, the commander-in-chief sent regiments after regiments into a bloody battle and announced that he himself was going on an assault: the Russians were repulsed at all points with the loss of 8,000 people.

The Turkish vizier became emboldened and decided to put Kamensky in the same position in which he had placed Bagration the year before. Up to 40,000 Turks settled near Rushchuk at Batyn, in four fortified camps, under the command of a seraskir. But Kamensky was just waiting for the enemy to appear in an open field: he quickly attacked the seraskir and on August 26, 1810, completely defeated him. The consequences of the Batyn victory were very important for the course of the Russian-Turkish war of 1806-1812: Rushchuk, Zhurzha, Nikopol surrendered. The Russians were firmly entrenched on the right bank of the Danube.

The Sultan, however, did not express an inclination towards peace: secretly instigated by French agents, he decided to continue the Russian-Turkish war and prepared for it all the more zealously because the army of Alexander I on the Danube, from the very beginning of 1811, was reduced to half by the separation of five divisions to the shores Dniester on the occasion of the disagreements that arose then with France. Moreover, the storm of Turkey was gone: Kamensky fell into a serious illness and soon ended his glorious life.

General Kutuzov, appointed as his successor in the spring of 1811, was forced to act defensively in the war and did not reveal in the eyes of the Turks either the courage or determination of his predecessor. They were encouraged. The vizier left Shumla and with enormous forces moved towards the Danube to oust the Russians from the fortresses they occupied. In fact, Kutuzov cleared Rushchuk, Silistria, Nikopol, crossed to the left bank and settled down near the town of Slobodzeya. It was a net spread by the mind of the great commander for the enemy.

Portrait of M. I. Kutuzov. Artist J. Doe, 1829

Both the Russian and Turkish armies stood inactive for two months, one in full view of the other, separated only by the river. The vizier finally decided with his main forces to also cross the Danube, four versts above the Russian camp, met almost no resistance and established himself on the left bank, near Slobodzeya; but soon paid dearly for this success. Kutuzov immediately ordered redoubts to be built against the Turkish camp in a semicircle so that the enemy could not move forward a single step; Meanwhile, General Markov ordered a separate corps to quietly move to the right bank and cut off the communication between the vizier and Rushchuk. Markov carried out his assignment with brilliant success; on October 1, 1811 he attacked the Turks who were standing near Rushchuk by surprise, scattered them without difficulty, positioned himself directly opposite the Turkish camp, directed Turkish cannons at it and began a brutal cannonade. The vizier realized the full danger of his position and escaped captivity by secret flight to Bulgaria. His army, consisting of Janissaries and selected Turkish troops, mostly died at Slobodzeya from hunger and disease; the rest, numbering 12,000 people, with all the artillery, surrendered (November 23, 1811) to Kutuzov.

Such a cruel blow, depriving the Sultan of the means to continue the Russian-Turkish war, inclined him towards peace. By the Treaty of Bucharest (1812), Porta agreed to cede to Russia part of its possessions between the Dniester and the Prut, known as Bessarabia, with the fortresses of Khotin, Bendery, Akkerman, Kiliya and Izmail. The count's and soon afterwards the prince's dignity was Kutuzov's reward for his brilliant feat, crowned with the much-coveted peace. A rare treaty was as beneficial for Russia due to the circumstances of the time as the Treaty of Bucharest: it ended the painful Russian-Turkish war of 1806-1812 at the very time when the fatherland needed to concentrate all its forces on the western border to fight all of Europe. Turkey reconciled with us a month before Napoleon's invasion of Russia, and Alexander approved the treaty in Vilna, already on a campaign against a formidable enemy.

When writing the article, recycled materials were used from the book by N. G. Ustryalov “Russian History before 1855”

Petersburg's protest remained unanswered. Then Alexander I sent troops under the command of General Ivan Michelson into Moldavia and Wallachia. By this, the Russian emperor tried to prevent the possible appearance of French units in the Danube principalities, which at that time landed in Dalmatia. In response, Türkiye declared war on the Russian Empire in 1806.

Campnia 1807. At the beginning of 1807, the main forces of the Russians fought against the French in Prussia. On the Danube, Mikhelson had approximately 40 thousand people against the Turks. With these limited forces he had to operate on a thousand-kilometer Danube front. Therefore, Mikhelson was given a mainly defensive task - to hold the already occupied left bank of the Danube. Due to a lack of forces, the Russians were unable to capture the remaining fortresses of the Turks on the left bank of the Danube (Izmail, Brailov and Zhurzha). But the attempts of the Turkish command to seize the initiative on the left bank were repelled.

Battle of Obilesti (1807). At the beginning of the summer of 1807, the Turkish command planned to capture Bucharest and drive the Russians out of Moldavia and Wallachia. To do this, two large Turkish detachments (40 and 13 thousand people) moved towards Bucharest. At that time, a 4.5 thousand detachment led by General Mikhail Miloradovich was in Bucharest. He decided to act offensively and prevent the Turkish forces from uniting. Having spoken out against a 13,000-strong detachment under the command of Mustafa Pasha, Miloradovich attacked the Turks near the village of Obilesti on June 2, 1807 and inflicted a heavy defeat on them. In this battle, the Turks lost 3 thousand people, the Russians - 300 people. The defeat at Obilesti forced the Turkish troops to abandon the attack on Bucharest and retreat beyond the Danube. This was the largest victory of the Russian army in the 1807 campaign.

Battle of the Dardanelles (1807). A little earlier, the Russian squadron in the Mediterranean under the command of Admiral Dmitry Senyavin (10 battleships, 1 frigate) also achieved a significant victory. In February she set sail from her base in the Ionian Islands to the Dardanelles. Senyavin planned to begin a blockade of the straits in order to deprive the capital of Turkey of food supplies from the Mediterranean Sea. On March 6, 1807, the Russian squadron blocked the Dardanelles. After two months of blockade, the Turkish fleet under the command of Kapudan Pasha Seyit Ali (8 battleships, 6 frigates and 55 smaller ships) left the strait on May 10 and tried to defeat Senyavin. On May 11, the Russian squadron attacked Turkish ships, which, after a hot battle, again took refuge in the strait. On May 11, the Senyavin squadron burst into the strait. Despite the fire from coastal batteries, she tried to destroy the 3 lagging damaged Turkish battleships, but they still managed to escape. On the same day, Senyavin returned to his original positions and again moved to blockade the strait.

Battle of Athos (1807). In June, Senyavin, with a demonstrative retreat, lured the Seyit-Ali squadron (9 battleships, 5 frigates and 5 other ships) from the strait, and then, with a skillful maneuver, cut off its retreat routes. On June 19, 1807, Senyavin forced Seyit-Ali to fight near the Athos Peninsula (Aegean Sea). First of all, the Russians concentrated fire on 3 Turkish flagships. Senyavin took into account the psychology of Turkish sailors, who usually fought steadfastly as long as the flagship was in the ranks. In the direction of the main attack, Senyavin managed to create superiority in forces. Five Russian ships blocked the path of 3 Turkish flagships, surrounded them in a semicircle and attacked from a short distance. Attempts by other Turkish ships to come to the aid of their flagships were thwarted by an attack by other groups of Russian ships. In the afternoon, the Turkish fleet began a disorderly retreat. He lost 3 battleships and 4 frigates. The Russian squadron had no losses in ships. The victory in the Battle of Athos led to the dominance of the Russian fleet in the Aegean Sea and forced Turkey to accelerate the signing of an armistice with Russia.

Battle of Arpacz (1807). At the same time, in the Caucasian theater of military operations, on the banks of the Arpachay River (Armenia) on June 18, 1807, a battle took place between the Turkish army under the command of Yusuf Pasha (20 thousand people) and the Russian army under the command of General Ivan Gudovich (7 thousand . people). Having concluded a truce with the Persians, Gudovich moved against the Turks in three detachments to Kara, Poti and Akhalkalaki. However, the dispersion of forces led to the fact that the Russian onslaught was repelled from everywhere. After this, the Turks launched a counteroffensive. Gudovich managed to gather his troops and retreated with them to the area of the Arpachay River, where he gave battle to the army of Yusuf Pasha. Despite their triple numerical superiority, the Turks were defeated and retreated. For the victory at Arpachai, Gudovich received the rank of field marshal.

Truce (1807). Thus, in June 1807, Turkey suffered defeats both on both land fronts and at sea. That same month, her hopes for French assistance also vanished. After the Peace of Tilsit, Napoleon became an ally of Russia and mediated the Russian-Turkish truce in August 1807. On the Russian side, a truce was concluded by General Meyendorff, who replaced the deceased Michelson. According to the terms of the truce, Russian troops left the Danube principalities, and the Turkish army retreated to the Adrianople area. However, Alexander I was dissatisfied with these conditions and ordered the withdrawal of Russian troops from Moldavia and Wallachia to be suspended. After the end of the war with France, Russian troops on the Danube were increased to 80 thousand people. They were led by 76-year-old Field Marshal Alexander Prozorovsky.

Campaign of 1808-1809. The year 1808 passed in Russian-Turkish negotiations. In September, a meeting between the Russian and French emperors took place in Erfurt. There, Napoleon, who was experiencing serious difficulties in Spain, agreed to the annexation of Moldavia and Wallachia to Russia in exchange for the support of Alexander I in a possible fight between France and Austria. The consent of the largest continental power to Russia's freedom of action in Turkey freed the hands of the Russian emperor. In 1809, military operations on the Danube were resumed. But despite the favorable international situation, Alexander I was unable to do so in 1809-1810. defeat Turkey and achieve their territorial goals. There are three important reasons here. Firstly, the Russian command did not have a single clear plan of action beyond the Danube. During these two years, three commanders changed in this theater, each of whom led in his own way. Secondly, the traditional specificity of this region affected, where problems of supply, protection from heat, epidemics, knowledge of the area, etc. came to the fore. All these serious difficulties could not be adequately overcome. Thirdly, it is necessary to note the fighting qualities of the Turkish army. Despite the defeats, she did not stop fighting and did not give the Russians the opportunity to achieve an overwhelming advantage.

In the spring of 1809, Prozorovsky's army acted mainly against Turkish fortresses along the Danube. In August, Prozorovsky died and General Pyotr Bagration became commander. On August 14, he crossed the Danube and occupied Dobruja. But the Russians were unable to capture the fortress of Silistria, the siege of which dragged on. Taking advantage of the diversion of Bagration's forces in Dobrudja, the Turks crossed to the left bank of the Danube at Zhurzhi and began an attack on Bucharest with large forces (up to 40 thousand people). But on August 29, they were repulsed at Frasino by a much smaller Russian detachment of General Langeron and retreated across the Danube. Nevertheless, the activity of the Turks forced Bagration to scatter his forces over a large territory - from Serbia to the port of Varna. As in his time, Rumyantsev and Bagration near Silistria suffered from the same ailments - lack of fodder and uniforms, diseases. When in October a 50,000-strong Turkish army moved from Rushchuk to the rescue of Silistria, Bagration did not take risks, lifted the siege and crossed to the left bank of the Danube. This year brought the Russians only the capture of a number of fortresses along the left bank - Tulcha, Isakchi, Izmail and Brailov. In 1810, instead of Bagration, the young general Nikolai Kamensky 2nd was appointed commander-in-chief. Taking advantage of the fact that the main forces of the Turks were in Serbia at that time, the new commander decided to defeat the Turkish troops in northern Bulgaria before reinforcements approached them. In May, he and his brother Kamensky 1st crossed the Danube. Kamensky 2nd moved with a 25,000-strong detachment to Silistria. Kamensky 1st with an 18,000-strong detachment went south, to Bazardzhik, to stop the movement of Turkish troops to the rescue of Silistria.

Battle of Bazardzhik (1810). On May 22, 1810, near Bazardzhik (Pazardzhik), a battle took place between the detachment of General Kamensky 1st and the Turkish corps under the command of Pelivan Pasha (10 thousand people). The Turks suffered a severe defeat and retreated, surrendering Bazardzhik. Russian losses amounted to 1.6 thousand people. The Turks lost 5 thousand people. (including 2 thousand prisoners). In honor of this victory, a special gold cross “For excellent courage during the capture of Bazardzhik” was issued to the officers participating in the battle. This success of the Russians decided the fate of Silistria. On May 30, its garrison capitulated.

Siege of Shumla and Rushchuk (1810). After the capture of Silistria, Kamensky 2nd, without wasting any time, moved at the head of an army of 35,000 to the Turkish fortress of Shumla. This Turkish stronghold in Bulgaria was defended by large forces (up to 40 thousand people). Having reached Shumla on June 10, Kamensky the next day, virtually without preparation, stormed this stronghold. The attack was repelled. In July, Kamensky, having lost hope of quickly capturing such powerful fortifications and fearing a possible attack by a large Turkish landing force from Varna, lifted the siege. The Russian commander retreated north to Rushchuk (now the Bulgarian city of Ruse). This strong Turkish fortress on the right bank of the Danube was defended by a 20,000-strong garrison under the command of Commandant Bosniak Aga. On July 22, 1810, Kamensky stormed Rushchuk. This attack was characterized by great brutality and bloodshed. The besieged did not limit themselves to passive defense. They resolutely counterattacked the attackers in the ditch, preventing them from climbing the rampart. Despite heavy losses, Kamensky stubbornly threw more and more forces into the battle, turning the attack into a merciless massacre. The assault ended in complete failure. The troops sent to attack (17 thousand people) failed to take the fortress, losing more than half of their strength under its walls.

Battle of Batyn (1810). At the beginning of August 1810, Turkish troops in northern Bulgaria, having received reinforcements, went on the offensive and moved from both sides to the rescue of the Rushchuk fortress, besieged by Kamensky. An army under the command of Osman Pasha (60 thousand people) was advancing from the Shumla region, and the army of Seraskir Kushakchi (30 thousand people) was advancing from the Yantra River. Kamensky 2nd did not passively wait for the connection of Turkish forces. With a 21,000-strong army, he decisively set out to meet the smaller troops of Kushakchi and on August 26, in the Batyn area, inflicted a crushing defeat on them. Russian losses amounted to 1.4 thousand people. The Turks lost (killed, wounded and captured) 10 thousand people. The Batyn victory had a decisive influence on the course of the 1810 campaign. After this battle, the Turks stopped offensive operations. The Batyn victory also decided the fate of Rushchuk. On September 15, 1810, its garrison, having lost hope of outside help, capitulated. By the end of the year, Kamensky cleared the northern part of Bulgaria from the Turks, but did not dare to move through the Balkans due to a lack of fodder and the onset of cold weather. Leaving three divisions on the right bank at the crossings, Kamensky took the remaining six to Wallachia for the winter. The following year, the young commander was preparing for a campaign in the Balkans, but in the winter he became seriously ill and was sent to Odessa, where he died in the spring.

Campaign of 1811. General Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov became the new commander. By that time, the international situation had already changed significantly. Due to the threat of war with Napoleon, half of the Russian forces were transferred from the Danube theater of operations to the western borders. Kutuzov had only 46 thousand people left. A cautious and prudent commander, Kutuzov abandoned the Balkan campaign and began to act in his usual manner, when success was achieved through the mistakes of the enemy who had gained the initiative. In order not to disperse his forces, Kutuzov even left a number of fortresses (for example, Silistria), having previously destroyed them. He concentrated his main troops in the most important strategic direction at Ruschuk, through which the main road to Bucharest ran. Here the Russian commander began to wait for further actions of the Turks. Kutuzov secured his far right flank at the Danube crossing near the Vidin fortress by purchasing all the crossing means from the Vidin Pasha, and for greater reliability he sent a 6,000-strong detachment of General Zass there for defense.

Ruschu-Slobozeya operation (1811). Kutuzov's passivity and the general weakening of Russian forces on the Danube pushed the Turkish command to take active action. At the beginning of summer, a 60,000-strong army under the command of Vizier Akhmet Pasha moved from Shumla to Ruschuk. On June 22, 1811, she attacked Kutuzov’s army (15 thousand people) near Rushchuk. But the Russians repelled the onslaught with artillery fire and counterattacks. The Turks lost 5 thousand people, the Russians - 500 people. Akhmet Pasha retreated and began to dig in, expecting Kutuzov's attack. But the Russian commander, not wanting to take risks, soon retreated with his small army to the left bank of the Danube, blowing up the Rushuk fortifications. On August 28, encouraged, Akhmet Pasha crossed with part of his forces (36 thousand people) after the Russians and on August 31 set up camp in Slobodzeya. Knowing the previous failures of the Turkish offensive on the left bank, Akhmet Pasha decided to wait until the Russians themselves attacked him. To do this, he strengthened his camp, giving the initiative to Kutuzov. He also had another plan - to cut off the Turks from communication with Rushchuk.

On a dark autumn night, General Markov’s detachment (7.5 thousand people) secretly crossed back to the right bank of the Danube and with a surprise attack on October 2 completely defeated the Turkish army at Rushchuk, which did not expect an attack. The Russians defeated an army of 20,000, most of which were captured or fled. In addition, a huge camp with all its food supplies and weapons was captured. The Russians lost only 9 people during the attack. killed and 40 wounded. After this, the Slobodzeya camp of the Turks on the left bank was blocked by the troops of Kutuzov, who summoned 2 divisions from northern Moldova that had not yet had time to go west. Akhmet Pasha fled to Ruschuk, leaving his soldiers to their fate. Kutuzov did not interfere with his escape, because he knew that according to Turkish law, the vizier could not negotiate peace while surrounded. After the vizier crossed to the right bank of the Danube, Kutuzov’s adjutant soon arrived, who congratulated the Turkish commander on his successful rescue and offered to begin peace negotiations. The Slobodzeya camp lost hope of outside help and was completely surrounded. Deprived of the supply of ammunition and food, the Turkish army in Slobodzeya suffered severe hardships. It suffered heavy losses from hunger, disease and artillery shelling. On November 23, 1811, Akhmet Pasha signed the act of surrender of the remnants of his army in Slobodzei. By that time it had decreased to 12 thousand people.

Peace of Bucharest (28 May 1812). Kutuzov’s Rushchuk-Slobodzeya maneuver decided the outcome of the war. After the loss of an entire army in the area of Rushchuk and Slobodzeya, Turkey entered into negotiations, which ended with the signing of a peace treaty (1812). According to its terms, the area between the Prut and Dniester rivers (Bessarabia) went to Russia. The treaty was signed on May 16 and ratified by Emperor Alexander I on June 11, the day before Napoleon's troops invaded Russia. The timely completion of the war with Turkey made it easier to repulse the Napoleonic invasion. In this war with Turkey, the number of deaths in the Russian army reached 100 thousand people. (of these, more than two thirds were those who died from disease).

Shefov N.A. The most famous wars and battles of Russia M. "Veche", 2000.

"From Ancient Rus' to the Russian Empire." Shishkin Sergey Petrovich, Ufa.

In the autumn of 1806, the Russian-Turkish war began. Its initiator was Ottoman Turkey. Within two months, the Russian army captured the most important cities in the Danube lowland (Iasi, Bendery, Akkerman, Chilia, Galati, Bucharest) and reached the banks of the Danube. However, Russian troops soon began to go on the defensive. The Danube Army, numbering only about 35 thousand people, did not receive new reinforcements, since at the same time Russia was conducting military operations in East Prussia.

After the conclusion of the Peace of Tilsit, the Russian government entered into negotiations with Turkey. In August 1807, a truce was concluded, which Turkey very soon violated, which led to the resumption of hostilities. The siege of the fortresses of Zhurzha and Brailov began.

In the spring of 1809, Russian troops failed near Brailov. This strong fortress was captured only in the fall, when P.I. Bagration took command of the Russian army. By winter, Bagration withdrew his troops to Moldavia and Wallachia.

In the spring of 1810, hostilities resumed. General N.M. Kamensky was appointed commander-in-chief; under his leadership, Russian troops captured Silistria, Turtukai and Bazardzhik and approached the Shumla fortress. Despite the successes achieved, Kamensky withdrew his troops deep into Wallachia to winter quarters. Meanwhile, Russia's relations with France became increasingly tense. War was coming. It was necessary to end the war with Turkey, which had already lasted for the fifth year, as quickly as possible, forcing it to conclude a peace beneficial to Russia, depriving Napoleon of the opportunity to use Turkey as an ally.

In March 1811, M.I. Kutuzov was appointed commander-in-chief of the Moldavian army. On April 1, 1811, he arrived at the army. The situation was very difficult. In connection with the looming threat of invasion by Napoleonic troops, half of the Moldavian army was transferred to the western borders. Kutuzov had only four divisions, several Cossack regiments and the Danube flotilla at his disposal, a total of 46 thousand people. The Turkish army of 80 thousand people was preparing for the offensive. Kutuzov decided to use completely new tactics in waging war against the Turks. He abandoned the siege of fortresses. His plan was to force the enemy to leave the strong fortress of Shumla to Rushchuk, draw the Turks to the northern bank of the Danube and defeat them there. On July 4, 1811, 4 km south of Ruschuk, on the southern bank of the Danube, a fierce battle broke out. 15 thousand Russian soldiers fought against 60 thousand Turks. After a 12-hour battle, having lost 4 thousand people, the Turks fled all the way to Shumla. For strategic reasons, four days later Kutuzov withdrew his army from Rushchuk to the left bank of the Danube, having previously blown up the fortress. The withdrawal of Russian troops from Rushchuk, as Kutuzov expected, was regarded by the Turkish command as a weakness of the Russians. The vizier occupied the fortress abandoned and destroyed by Russian troops with his troops.

On the night of September 10, Turkish troops numbering 40 thousand people began crossing the Danube to the left bank. By mid-September, they transferred most of their troops across the Danube, leaving a 20,000-strong reserve on the right bank. Kutuzov developed an operation to encircle the main enemy forces and on October 13, 1811, he ordered a 7.5 thousand-strong detachment of infantry and cavalry under the command of General Markov to secretly cross to the right bank of the Danube. On October 20, the detachment suddenly attacked the Turkish camp in Rushchuk, defeated it and turned its guns against the Turkish troops on the left bank. At the same time, the encirclement of the main enemy forces began. There were fierce battles and continuous artillery shelling of the encircled Turkish army for ten days. In these battles the Turks lost more than two-thirds of their strength. Defeated and deprived of its army, Turkey made peace with Russia on May 28, 1812 (the Peace of Bucharest).

Many Decembrists took part in the Russian-Turkish war.

As part of the 13th artillery brigade, Lieutenant A.K. Berstel in 1809, “from September 8 to 14 August, was at the blockade and conquest of the Izmail fortress, where, during a sortie from the fortress to the battery, from September 10 he was in actual battle, for which and awarded the Order of St. Anna of the 4th degree".

Since 1810, the headquarters captain was on the Russian-Turkish front under the commander-in-chief of the Danube Army, General N.M. Kamensky. From June 4 to June 11, he took part in the siege and capture of Silistria, attacked by the Russian army and the Danube flotilla. Volkonsky participated in negotiations on the surrender of Silistria. “When the terms were concluded,” he “was sent to Silistria to receive the keys of the city and military banners.” In June, he was “near the city of Shumla and in many other affairs at this fortress”, he fought in a separate detachment of Lieutenant General A.L. Voinov. Participated in expeditions to the Balkan Mountains, in the battle of Eskistanbul. In July, he fought against Turkish troops under the command of Kushanets Pasha, who dug in on the right bank of the Yantra, near Batin. The battle ended in the complete defeat of the Turkish corps. Then Volkonsky was again at the siege of the Rushchuk fortress. In 1811, for military service, he was promoted to captain and awarded the title of aide-de-camp.

With the appointment of Kutuzov to the post of commander-in-chief, Volkonsky “was under the commander-in-chief of the Danube Army, infantry general Golenishchev-Kutuzov.” He was sent to the most dangerous combat missions. On October 13, as part of the corps of Lieutenant General Markov, he took part in the crossing of the Danube, and on October 14, in the battle of Slobodzeya. The Turkish troops were surrounded, the vizier's camp was stormed, and the vizier himself fled.

Staff captain of the 32nd Jaeger Regiment A.G. Nepenin had been on the Russian-Turkish front since the end of 1809. He participated in many military operations. On June 3, 1810, he was during the assault on the Bazardzhik fortress. For his distinction in this matter, he “received the highest favor and a gold badge on the St. George’s Ribbon.” On July 12-30, Nepenin was among the troops besieging the Varna fortress. “During this time, he was sent with a company through the Black Sea estuary to the mountains to cross communications with the 6th fortress from Shumla and was daily in a skirmish with the Turks, participated in the blockade of Shumla.”

As part of the 37th Jaeger Regiment, ensign K. A. Okhotnikov took part in the siege and then in the capture of the fortress of Silistria on June 11, 1810. Then he was continuously in battles near the city of Shumla, and then during the siege and assault of Rushchuk. He was awarded the rank of second lieutenant. In the campaign of 1811, he took part in the battle on February 12 near the town of Lovchi in the vanguard under the command of General Saint-Prix. On the night of September 9-10, he fought “while crossing the enemy to the left bank of the Danube River, where he received a concussion” in the head. He took part in the siege of the “Turkish camp under the leadership of the Supreme Vizier himself,” and then was “in the capture of all Turkish troops under the protection of Russia,” that is, with the complete surrender of the Turks on December 5, 1811.

Lieutenant of the Moscow Grenadier Regiment I. S. Povalo-Shveikovsky fought “in Moldova, Wallachia and Bessarabia against the Turks” from 1808. The formal list testifies to his extraordinary courage. In April - May 1809 he took part in the blockade of Brailov. On April 28, he was “in the hunters with the Cossacks against the enemy, who made a sortie from the fortress.” On September 10, he voluntarily went on a raid with the Cossacks in the vicinity of the Zhurzhi fortress. Then he fought in the vanguard of the Russian troops under the command of the Cossack colonel Grekov against the Turks under the command of Bishnyak Aga at the village of Deifosiya. In September he was under the fortress of Silistria. On October 10, his unit crossed the Danube to Moldova, where on December 3 he took part in the capture of Brailov. On June 3, 1810, Povalo-Shveikovsky fought in the daylight assault and capture of the Bazardzhik fortress. He was the first to break into the rampart “and thereby contributed to the capture of the city.” For excellent courage he was awarded the Order of Vladimir, 4th degree with a bow. From June 23 to August 4, he took part in the blockade of the Shumla fortress and “the defeat of the enemy corps of 30,000 who made a sortie from the fortress.” For his bravery he was promoted to staff captain.

Povalo-Shveikovsky became famous throughout the army for his bravery. Commander-in-Chief N.M. Kamensky, as a sign of favor, sent him to Alexander I “with a report of victory.”

In 1811, during the assault and capture of the city of Lovchi (February 12), Povalo-Shveikovsky was wounded. “For his distinction he was promoted to captain” and appointed divisional adjutant of the 2nd Grenadier Division. In February and March 1811, he “was sent with two companies” to the Balkan Mountains with the task of observing the enemy in order to prevent him from connecting with reinforcements. On March 12, after this expedition, he crossed the Danube River at the Nikopol fortress in Khotyn, and in September 1811 he was recalled “to his borders to the cantonary quarters in the Kamenets-Podolsk province.”

Lieutenant of the Mingrelian infantry regiment in the Danube Army in May 1810 participated in the siege of Silistria, and in July fought near the city of Shumla. From July 12 to July 22, he was at the siege of Rushchuk, on July 29-30, “during the defeat of the Turks at the Yantra River,” and on September 27, during the assault on the Rushchuk fortress. In 1811 he was in Lesser Wallachia, where he took part in numerous military affairs. For storming the batteries on the island against the Lom Palanka fortress on August 8, Tiesenhausen was promoted to captain. For military services on September 19 in the battle near the village of Kalafat, he was awarded the Order of Vladimir, 4th degree with a bow.

As part of the Kostroma Musketeer Regiment, Staff Captain I. N. Khotyaintsev took part in the siege of the Shumla fortress in April - June 1810, and from July 9 - in the blockade and then the assault on the Rushchuk fortress. For distinction he was promoted to captain.

In the wars of 1805-1811. The older generation of Decembrists participated. They began their combat military career at a very young age, 15-20 years old. This did not stop them from distinguishing themselves in battles, showing extraordinary courage, receiving high awards and promotions, and performing special tasks. Some of them, thanks to their military deeds, became personally known to the high command of the Russian army. Many of them already at that time began to be interested in political problems and be critical of what was happening in Russia. A new generation of patriots, who sought to prove their love for the Motherland with their blood, was preparing to join the older generation that had matured in battle. They understood the inevitability of a clash with Napoleonic France and prepared for it. Hard battles still lay ahead.

One of them was A. N. Muravyov. In 1810, he was accepted into the retinue of the quartermaster unit, which was later transformed into the General Staff. Already at this time he became close to M.F. Orlov, and, that is, with those who later entered the first secret society in Russia.

In 1811, in Moscow, in the house of A.N. Muravyov’s father, N.N. Muravyov Sr., the Mathematical Society met, and then a school of column leaders was opened. Students of the school and members of the Mathematical Society were A. N. Muravyov, M. N. Muravyov, I. G. Burtsov, Pyotr and Pavel Koloshin. They were all friends with each other and showed interest in political problems.

In 1810-1811 In Moscow, a secret circle “Youth Fellowship” was organized - an early pre-Decembrist organization, headed by 16-year-old warrant officer N. N. Muravyov, brother of the Decembrist. Its goal was to organize a new republican society on some remote island, such as Sakhalin. Muravyov wanted to “take reliable comrades with him, educate the inhabitants of the island and form a new republic, for which the comrades ... pledged to be (his) assistants.” He composed the laws of this society, the purpose of which was to create true, free citizens from the inhabitants of the island and to form a republic there on the basis of equality of people. The “Youth Fellowship” included Artamon Muravyov, Matvey Muravyov-Apostol, Lev and Vasily Perovsky. Friends convened meetings, read and discussed the composed laws of their partnership, and developed secret conventional signs that were exchanged between members of the fellowship during meetings. This circle ended its existence with the outbreak of the War of 1812.

Young Vladimir Raevsky and, studying in the 2nd Cadet Corps, “spent whole evenings in patriotic dreams, for the terrible era of 1812 was approaching.” As Batenkov later showed during the investigation, they “developed free ideas for each other,” hated the fruntomania of the Tsar and Tsarevich Konstantin, and dared to speak “about the Tsar as if he were a person and condemn the actions of the Tsarevich.” “Going to war,” Raevsky wrote, remembering Batenkov, “we parted as friends and promised to get together so that when we matured, we would try to put our ideas into action.”

In 1811, in St. Petersburg, he again organized a circle of young officers of the Izmailovsky regiment to study military sciences.

He subsequently recalled: “Two unsuccessful wars with Napoleon, the third, which threatened... the independence of Russia, forced (young) Russian patriots to devote themselves exclusively to military rank. The nobility, patriotically sympathizing with the decline of our military glory in the wars with France of 1805-1807. and foreseeing a quick break with her, he hurried to join the ranks of the army ready to meet Napoleon. All decent and educated young people, despising civil service, joined the military.”

In the answers to the Commission of Inquiry he wrote: “Upon entering service before the War of 1812, I turned all my attention to military sciences.”

History of the Russian army. Volume two Zayonchkovsky Andrey Medardovich

Russo-Turkish War 1806–1812

Pavel Markovich Andrianov, Lieutenant Colonel of the General Staff

The situation before the war

The forces of the warring parties? Theater of war? Prerequisites for the deployment of military operations by Russia and Turkey

During the brilliant century of the reign of Catherine II, Russia for the first time shook the power of the Turkish Empire.

At the beginning of the 19th century. Russia, as part of a coalition of European states, was passionate about the fight against Napoleon. As a far-sighted and skillful politician, Napoleon sought to weaken Russia, in which he saw his most dangerous enemy, and made every effort to disrupt its peaceful relations with Turkey. The brilliant Austerlitz victory raised Napoleon's prestige and shook the political importance of his enemies. Considering Russia weakened by the fight against Napoleon, Turkey in 1806 sharply changed the course of its policy. Dreaming of the return of Crimea and the Black Sea lands, Turkey is hastily preparing for a new war with Russia, no longer hiding its clearly hostile intentions. Emperor Alexander I, passionate about the fight against Napoleon, understood that a new war with Turkey was untimely for Russia. However, after unsuccessful attempts to force Turkey to fulfill its obligations arising from previously concluded peace treaties, Alexander I had to break the peace. In the fall of 1806, while saving Prussia on the Vistula from its final defeat by Napoleon, Russia was simultaneously forced to become involved in a long and stubborn struggle on the southern front in order to protect its violated interests.

The forces of the warring parties. To fight Turkey, Russia could deploy only a small part of its regular army. The bulk of Russian troops were concentrated in the western region and East Prussia. In October 1806, a 35,000-strong army was moved to Bessarabia under the command of cavalry general Michelson. This small Russian army was distinguished by its excellent fighting qualities. In the ranks of the troops one could count many veterans - participants in Suvorov's campaigns. The previous wars with the Turks served as an excellent combat school for Russian troops. Rational methods of fighting against a unique enemy were developed. The reforms of Emperor Paul did not eradicate in the troops those real combat techniques of warfare and combat, which were acquired by soldiers not during parades and parades, but in difficult campaigns and in the bloody battles of Rumyantsev and Suvorov.

Turkey, as during previous wars with Russia, did not have a permanent regular army. The large corps of Janissaries continued to play a leading role as the country's armed force. The political influence of the Janissaries at this time was very great. The unlimited rulers of the faithful - the Turkish padishahs - had to take into account the mood of the Janissaries in all their affairs in governing the country and even in foreign policy. With their growing political influence, the Janissaries lost those exceptional fighting qualities that at one time gave them the glory of invincibility and made them a threat to the Christian peoples of Southern Europe. Lack of training, lack of unity in action and passivity were noted in previous wars, when the Janissaries had to face a new formidable enemy on the northern front. Nevertheless, even with the indicated shortcomings, the Janissary corps was the core, the basis of the Turkish army. Around the corps of the Janissaries in times of disaster, at the call of the Sultan, an army was gathered, consisting of untrained militias, dashing riders, semi-wild nomads, who appeared at the call of their master from remote places in Asian countries. This crowd was excellent military material, but without the necessary training, without discipline, too susceptible to all military failures and of little use for large offensive operations. In addition to the central army, which came under the jurisdiction of the grand vizier, the rulers of the regions and the commandants of the fortresses had at their disposal troops almost completely independent of the central government. The training, equipment and armament of these provincial troops depended entirely on the talents of their commanders. These troops were extremely heterogeneous, had no cohesion among themselves and acted exclusively to protect regional interests.

As a common feature common to all Turkish troops, it should be noted their exceptional ability to defend both in the field trenches and behind the fortress walls, where they always show stubborn resistance. In a short time, the troops erected masterful engineering fortifications, created artificial barriers in front of the front, etc.

In all periods of the war, the Turkish army significantly outnumbered the Russian army, which could not compensate for the lack of training and the lack of proper unity in management and actions.

Theater of War. The theater of military operations was Bessarabia, which constituted a Turkish province, Moldavia and Wallachia, the so-called Danube principalities, which recognized the supreme power of the padishah, and Danube Bulgaria. The vast theater of military operations was limited in the east by the Dniester River and the Black Sea coast, in the north by the lands of the Hungarian crown, in the west by the Morava River and in the south by the Balkan Range. The terrain is steppe and flat throughout. Only in the north of Wallachia do the spurs of the Transylvanian Mountains rise, and to the south of the Danube not far away do the foothills of the Balkans begin. The only obstacles for the Russian army advancing from the northeast were large rivers: the Dniester, the Prut, the Danube. When moving south of the Danube, the harsh Balkan ridge grew along the way. During the rainy season, dirt roads were covered with a thick layer of stubborn mud. Villages and towns were rarely encountered along the way. Fertile fields provided good harvests, and the troops could count on abundant food supplies. Unhygienic living conditions in populated areas, and at the same time the abundance of earthly fruits, often caused widespread epidemics of dysentery and typhoid.

Theater of military operations in 1806

Owning the region and living among the conquered peoples, the Turks built many fortresses. The Dniester line was covered on the flanks by the fortresses of Khotyn and Bendery. The Danube flowed between a number of fortresses: on its left bank were Turno, Zhurzhevo, Brailov, Izmail and Kilia; on the right - Vidin, Nikopol, Rakhovo, Rushchuk, Turtukai, Silistria, Girsovo, Tulcea, Machin, Isakcha. The key to the Western Balkans was the strong fortress of Shumla, and the western Black Sea coast was strengthened by the fortresses of Kyustendzhi and Varna.

The sympathies of the population in almost the entire theater of war were on the side of the Russian army, the very appearance of which supported in the local residents a joyful hope for a better future, when, with the help of Russia, the heavy chains of slavery would fall.

Plans of the parties. Starting the war only out of necessity, under the pressure of Turkey’s defiant behavior, Russia designated the Danube principalities as the immediate target of action for its army. The capture of the principalities brought Russia closer to the Danube, which Emperor Alexander considered the natural border of the Russian Empire in the southwestern corner.

Turkey, counting on the assistance of Napoleon, hoped to return the Black Sea coast and restore the borders of its possessions to the extent that it occupied before Catherine’s wars. Thus, both sides were preparing to act offensively. With such plans, possession of the Danube River line was especially important for both sides. It was at this great milestone that the bloody events of the coming war took place.

From the book The Truth about Nicholas I. The Slandered Emperor author Tyurin AlexanderWar of 1806–1812 Peace of Bucharest After Napoleonic envoy General Sebastiani obtained from the Porte a ban on the passage of Russian ships through the Black Sea Straits - in direct violation of the Iasi Treaty - a new Russian-Turkish war broke out.

From the book Pictures of the Past Quiet Don. Book one. author Krasnov Petr NikolaevichWar with Turkey 1806-1812 In those difficult years, when Russia was at war with both the Swedes and the Turks, a song was formed on the Don: The Turkish Sultan writes, writes to the White Tsar, And the Turkish Sultan wants to take the Russian land: “I will take away all the Russian land, Stand in Moscow

From the book Non-Russian Rus'. Millennial Yoke author Burovsky Andrey MikhailovichRussian-Turkish War The Russian-Turkish War of 1878–1882 led to new victories for Russian weapons. Plevna and Shipka are no less famous and glorious names than Preussisch-Eylau and Borodino. 1878 - Russian troops defeat the Turks, they are ready to take Constantinople. But

From the book The Whole Truth about Ukraine [Who benefits from the split of the country?] author Prokopenko Igor StanislavovichRussian-Turkish War In the 13th century, the first Mongols appeared on Crimean soil, and soon the peninsula was conquered by the Golden Horde. In 1441, with the creation of the Crimean Khanate, a short period of independence began. But literally a few decades later, in 1478, the Crimean

From the book History of the Russian Army. Volume three author Zayonchkovsky Andrey MedardovichRusso-Turkish War 1877–1878 Konstantin Ivanovich Druzhinin,

author Platonov Sergey Fedorovich§ 134. Russian-Turkish War 1768-1774 At a time when the attention of Empress Catherine was turned to pacifying the Polish confederates and the Haydamak movement, Turkey declared war on Russia (1768). The pretext for this was the border robberies of the Haidamaks (who ravaged

From the book Textbook of Russian History author Platonov Sergey Fedorovich§ 136. Russian-Turkish War of 1787–1791 and Russian-Swedish War of 1788-1790 The annexation of Crimea and major military preparations on the Black Sea coast were directly dependent on the “Greek project”, which Empress Catherine and her collaborator were keen on in those years

From the book Textbook of Russian History author Platonov Sergey Fedorovich§ 152. Russian-Persian War 1826–1828, Russian-Turkish War 1828–1829, Caucasian War In the first years of the reign of Emperor Nicholas I, Russia waged great wars in the east - with Persia (1826–1828) and Turkey (1828–1829). Relations with Persia became cloudy at the beginning of the 19th century, due to

From the book An Artist's Life (Memoirs, Volume 2) author Benois Alexander NikolaevichChapter 6 RUSSIAN-TURKISH WAR The approach of war began to be felt long before its announcement and, although I was in that blissful state when they do not yet read newspapers and do not have political convictions, nevertheless, the general mood was reflected quite clearly on me. author Chernyshev Alexander

War with Turkey 1806–1812 Despite the defeats suffered in the Russian-Turkish wars of the second half of the 18th century, Turkey did not give up hopes of regaining Crimea and the Northern Black Sea region and restoring its dominant position in the Caucasus. Emboldened by Russia's defeat and

From the book History of Georgia (from ancient times to the present day) by Vachnadze MerabRussian-Iranian (1804–1813) and Russian-Turkish (1806–1812) wars and the issue of annexing the historical territories of Georgia. Since the beginning of the 19th century, Russian-Iranian and Russian-Turkish contradictions entered a new phase. Western European countries were not interested in Russia's exit

From the book The Influence of Sea Power on the French Revolution and Empire. 1793-1812 by Mahan Alfred author Vorobiev M N4. 1st Russian-Turkish War The war began, but it was not necessary to fight immediately, because the troops were far away. Then there were no trains or vehicles, the troops had to walk, they had to be collected from different points of the huge country, and the Turks were also swinging

From the book Russian History. Part II author Vorobiev M N2. 2nd Russian-Turkish War Preparing for a war with Turkey, Catherine managed to negotiate a military alliance with Austria. This was a major foreign policy success because the problems that had to be solved became much simpler. Austria could put up quite a

During the second year Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812) The squadron of Rear Admiral Semyon Afanasyevich Pustoshkin captured on May 11, 1807 the Turkish fortress of Anapa, located at the junction of the Greater Caucasus and the Taman Peninsula.

The capture of a well-fortified Turkish fortress marked the beginning of Russia's development of the Black Sea strip of the Caucasus, a future resort pearl.

Anapa Fortress was the northernmost fortification of the vast Turkish possessions on the eastern coast of the Black Sea.

For the Port, Anapa was not just a point on the map of the vast Ottoman Empire, not one of the many fortified port cities, but a strategically significant point in the Black Sea basin.

From the port of Anapa, Turkish ships went on predatory campaigns and raids on the lands of the Kuban coast that belonged to Russia.

Experienced in the art of intricate intrigues of eastern diplomacy, the Ottoman Empire skillfully incited the Caucasus mountaineers to forays and attacks on the Russian border territories.

The appearance of a powerful Russian squadron on the Anapa roadstead from 15 ships of the Russian Black Sea Fleet led by the flagship 110-gun ship "Ratny" came as a surprise to the Turks.

The aggressively-minded Turks of the Anapa fortress did not allow the Russian envoy to even approach the walls of the fortress to present an ultimatum of surrender. Considering this as a refusal of the Turks to surrender, the Russians began shelling the Anapa fortress from the sea; soon a fire broke out in the fortress and the entire Turkish garrison quickly fled from the city engulfed in flames. Even the Circassians who came to the rescue did not help the Ottomans - their cavalry attack was repulsed by the Russian landing force.

The winners of the battle for Anapa received rich trophies, including two merchant ships stationed in the port, about a hundred cannons and a lot of ammunition. At that time, Russia did not yet have enough forces and means to hold the occupied territory, and in order to eliminate the support base of Turkish rule on the Black Sea coast, the sailors blew up the Anapa fortress.

The lightning capture of Anapa by Russian sailors is a glorious episode during the first Russian-Turkish War in the 19th century (1806 - 1812). Istanbul's connection with the Caucasian mountaineers, who were hostile to the Russian Empire by the Turks, was severed.

A little more than two decades remained before the final annexation of Anapa to Russia (1829). With the entry of Anapa, a former Ottoman fortress, into Russia the dangerous banditry and slave-owning center near the southern borders of our country was eliminated. Thus, the prerequisites were formed for the peaceful development of the lands that became part of Russia and the future transformation of the region into a modern Caucasian resort city.

Treaty of Bucharest 1812.

May 16, 1812 A peace treaty was signed in Bucharest, under the terms of which Russia was to return the Anapa fortress to the Porte, a key point of Turkish possessions in the region.

According to the terms of the Bucharest Peace " All prisoners of war, both male and female, whatever their nationality and condition, located in both empires, must, soon after the exchange of ratifications of this peace treaty, be returned and handed over without the slightest ransom or payment."

The Treaty of Bucharest in 1812 improved the strategic position of Russia, which Bessarabia with the fortresses of Khotyn, Bendery, Akkerman, Kiliya and Izmail.

The Russian-Turkish border was established from now on along the Prut River and the Kiliya channel. Russia has left behind significant territories in Transcaucasia, received the right of commercial navigation along the entire course of the Danube.

Moldavia and Wallachia were returned to Turkey, which, in turn, restored to them all the privileges granted Treaty of Jassy in 1792. Serbia gained autonomy in matters of internal self-government.

- In contact with 0

- Google+ 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0