Brief biography of Joseph Brodsky

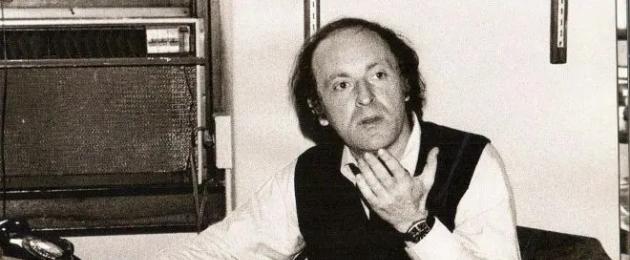

Joseph Alexandrovich Brodsky is an outstanding poet, translator, prose writer and playwright of the 20th century. Born on May 24, 1940 in Leningrad and was named Joseph in honor of Stalin. The father of the future writer was a fairly famous photojournalist, and his mother was an accountant. My childhood was spent in a small apartment in the house where Merezhkovsky and Gippius once lived. Alfred Nobel once studied at the school Brodsky attended. Much in the life of this extraordinary writer was symbolic. So, in adulthood he will become a Nobel Prize laureate.

Since childhood, Joseph Brodsky dreamed of becoming a poet and his dreams came true. However, before that, he went a long way in search of his calling. After graduating from eight-year school, he went to work at a factory, where he did hard work. He said about himself that he was a milling operator, a fireman, and an orderly. Later he participated in geological projects in Yakutia and the Tien Shan, while simultaneously studying English and Polish. Translation activities have fascinated Brodsky since the early 1960s. He was particularly interested in Slavic and English-language poetry. By the end of the 1960s, his name was already widely known in youth and informal literary circles.

In 1964, he was arrested and exiled to the Arkhangelsk region for five years. There he first worked on a collective farm, performing various feasible jobs, but due to health reasons he was released from it and appointed a photographer. Brodsky's first book, Poems and Poems, was published abroad in 1965. At the same time, thanks to petitions from such famous personalities as Akhmatova, Marshak, Shostakovich, the poet’s term of exile was shortened. In addition, his case has already received worldwide publicity. Returning to Leningrad, he wrote a lot, but they have not yet undertaken to publish it. Before his emigration, he was able to publish only some translations and 4 poems. In June 1972, the writer was forced to leave his homeland.

He emigrated to the USA, where he taught the history of Russian and English literature. Since 1973, he began publishing essays and reviews in English. In 1987, Brodsky became the fifth Russian to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 1989, the poet’s “case” was finally closed, and he was able to visit his homeland. The magazine "New World" undertook to publish a selection of poems by the already world-famous poet. Brodsky's massive publications followed. In the 1990s, the Pushkin Foundation published a collection of his works in 4 volumes. I. A. Brodsky died in January 1996 in New York.

When talking about the great poets of the 20th century, one cannot fail to mention the work of Joseph Brodsky. He is a very significant figure in the world of poetry. Brodsky had a difficult biography - persecution, misunderstanding, trial and exile. This prompted the author to leave for the USA, where he received public recognition.

Dissident poet Joseph Brodsky was born on May 24, 1940 in Leningrad. The boy's father worked as a war photographer, his mother as an accountant. When a “purge” of Jews took place among the officers in 1950, my father went to work as a photojournalist for a newspaper.

Joseph's childhood coincided with war, the siege of Leningrad, and famine. The family survived, like hundreds of thousands of people. In 1942, Joseph’s mother took him and evacuated to Cherepovets. They returned to Leningrad after the war.

Brodsky dropped out of school as soon as he entered the 8th grade. He wanted to help his family financially, so he went to work at a factory as an assistant milling machine operator. Then Joseph wanted to become a guide, but it didn’t work out. At one time he had a burning desire to become a doctor and even went to work in a morgue, but soon changed his mind. Over the course of several years, Joseph Brodsky changed many professions: all this time he voraciously read poetry, philosophical treatises, studied foreign languages, and even planned to hijack a plane with his friends to escape from the Soviet Union. True, things did not go further than plans.

Literature

Brodsky said that he began writing poetry at the age of 18, although there are several poems written at the age of 16-17. In the early period of his work, he wrote “A Christmas Romance”, “Monument to Pushkin”, “From the Outskirts to the Center” and other poems. Subsequently, the author’s style was strongly influenced by poetry, and they became the young man’s personal canon.

Brodsky met Akhmatova in 1961. She never doubted the talent of the young poet and supported Joseph’s work, believing in success. Brodsky himself was not particularly impressed by Anna Andreevna’s poems, but he admired the scale of the personality of the Soviet poetess.

The first work that alerted the Soviet Power dates back to 1958. The poem was called "Pilgrims". Next he wrote “Loneliness”. There Brodsky tried to rethink what was happening to him and how to get out of the current situation when newspapers and magazines closed their doors to the poet.

In January 1964, the same “Evening Leningrad” published letters from “indignant citizens” demanding that the poet be punished, and on February 13, the writer was arrested for parasitism. The next day he suffered a heart attack in his cell. Brodsky’s thoughts of that period are clearly discernible in the poems “Hello, my aging” and “What can I say about life?”

The persecution that began placed a heavy burden on the poet. The situation worsened due to a breakdown in relations with his beloved Marina Basmanova. As a result, Brodsky attempted to die, but was unsuccessful.

The persecution continued until May 1972, when Brodsky was given a choice - a psychiatric hospital or emigration. Joseph Alexandrovich had already been to a mental hospital, and, as he said, it was much worse than prison. Brodsky chose emigration. In 1977, the poet accepted American citizenship.

Before leaving his native country, the poet tried to stay in Russia. He sent a letter himself asking for permission to live in the country at least as a translator. But the future Nobel laureate was never heard.

Joseph Brodsky participated in the International Poetry Festival in London. Then he taught the history of Russian literature and poetry at the University of Michigan, Columbia and New York University. At the same time, he wrote essays in English and translated poetry into English. Brodsky's collection Less Than One was published in 1986, and the following year he received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In the period 1985-1989, the poet wrote “In Memory of the Father,” “Performance” and the essay “A Room and a Half.” These poems and prose contain all the pain of a person who was not allowed to see his parents off on their last journey.

When perestroika began in the USSR, Iosif Aleksandrovich’s poems were actively published in literary magazines and newspapers. In 1990, the poet’s books began to be published in the Soviet Union. Brodsky received invitations from his homeland more than once, but constantly delayed this visit - he did not want the attention of the press and publicity. The difficulty of returning is reflected in the poems “Ithaca”, “Letter to the Oasis” and others.

Personal life

Joseph Brodsky's first great love was the artist Marina Basmanova, whom he met in 1962. They dated for a long time, then lived together. In 1968, Marina and Joseph had a son, Andrei, but with the birth of the child, the relationship worsened. They separated that same year.

In 1990, he met Maria Sozzani, an Italian aristocrat with Russian roots on her mother’s side. That same year, Brodsky married her, and three years later their daughter Anna was born. Unfortunately, Joseph Brodsky was not destined to see his daughter grow up.

The poet is known as a famous smoker. Despite undergoing four heart surgeries, he never quit smoking. Doctors strongly advised Brodsky to give up the addiction, to which he replied: “Life is wonderful precisely because there are no guarantees, none ever.”

Joseph Brodsky also loved cats. He claimed that these creatures do not have a single ugly movement. In many photos, the creator is photographed with a cat in his arms.

With the support of the writer, the Russian Samovar restaurant opened in New York. The co-owners of the establishment were Roman Kaplan and. Joseph Brodsky invested part of the money from the Nobel Prize into this project. The restaurant has become a landmark of “Russian” New York.

Death

He suffered from angina pectoris even before emigration. The poet's health was unstable. In 1978, he underwent heart surgery, and the American clinic sent an official letter to the USSR asking that Joseph’s parents be allowed to travel to care for their son. The parents themselves submitted a petition 12 times, but each time they were refused. From 1964 to 1994, Brodsky suffered 4 heart attacks, he never saw his parents again. The writer's mother died in 1983, and a year later his father passed away. The Soviet authorities refused his request to come to the funeral. The death of his parents undermined the poet's health.

On the evening of January 27, 1996, Joseph Brodsky folded his briefcase, wished his wife good night and went up to his office - he had to work before the start of the spring semester. On the morning of January 28, 1996, the wife found her husband without any signs of life. Doctors declared death from a heart attack.

Two weeks before his death, the poet bought himself a place in a cemetery in New York, not far from Broadway. There he was buried, fulfilling the last will of the dissident poet, who loved his homeland until his last breath.

In June 1997, the body of Joseph Brodsky was reburied in Venice at the San Michele cemetery.

In 2005, the first monument to the poet was opened in St. Petersburg.

Bibliography

- 1965 – “Poems and Poems”

- 1982 – “Roman Elegies”

- 1984 – “Marble”

- 1987 – “Urania”

- 1988 – “Stop in the Desert”

- 1990 – “Fern Notes”

- 1991 – “Poems”

- 1993 – “Cappadocia. Poetry"

- 1995 – “In the vicinity of Atlantis. New poems"

- 1992-1995 – “Works of Joseph Brodsky”

Joseph Brodsky

short biography

Childhood and youth

Joseph Brodsky born May 24, 1940 in Leningrad. Father, captain of the USSR Navy Alexander Ivanovich Brodsky (1903-1984), was a military photojournalist, after the war he went to work in the photo laboratory of the Naval Museum. In 1950 he was demobilized, after which he worked as a photographer and journalist in several Leningrad newspapers. Mother, Maria Moiseevna Volpert (1905-1983), worked as an accountant. Mother's sister is an actress of the BDT and the Theater named after. V.F. Komissarzhevskaya Dora Moiseevna Volpert.

Joseph's early childhood was spent during the years of war, blockade, post-war poverty and passed without a father. In 1942, after the blockade winter, Maria Moiseevna and Joseph went for evacuation to Cherepovets, returning to Leningrad in 1944. In 1947, Joseph went to school No. 203 on Kirochnaya Street, 8. In 1950, he moved to school No. 196 on Mokhovaya Street, in 1953 he went to the 7th grade at school No. 181 on Solyanoy Lane and remained in the second year the following year. year. In 1954, he applied to the Second Baltic School (naval school), but was not accepted. He moved to school No. 276 on Obvodny Canal, house No. 154, where he continued his studies in the 7th grade.

In 1955, the family received “one and a half rooms” in the Muruzi House.

Brodsky's aesthetic views were formed in Leningrad in the 1940s and 1950s. Neoclassical architecture, heavily damaged during the bombing, endless vistas of the Leningrad outskirts, water, multiple reflections - motifs associated with these impressions of his childhood and youth are invariably present in his work.

In 1955, at less than sixteen years old, having completed seven grades and starting the eighth, Brodsky left school and became an apprentice milling machine operator at the Arsenal plant. This decision was related both to problems at school and to Brodsky’s desire to financially support his family. Tried unsuccessfully to enter submariner school. At the age of 16, he got the idea of becoming a doctor, worked for a month as an assistant dissector in a morgue at a regional hospital, dissected corpses, but eventually abandoned his medical career. In addition, for five years after leaving school, Brodsky worked as a stoker in a boiler room and as a sailor in a lighthouse.

Since 1957, he was a worker in geological expeditions of NIIGA: in 1957 and 1958 - on the White Sea, in 1959 and 1961 - in Eastern Siberia and Northern Yakutia, on the Anabar Shield. In the summer of 1961, in the Yakut village of Nelkan, during a period of forced idleness (there were no deer for a further hike), he had a nervous breakdown, and he was allowed to return to Leningrad.

At the same time, he read a lot, but chaotically - primarily poetry, philosophical and religious literature, and began to study English and Polish.

In 1959 he met Evgeny Rein, Anatoly Naiman, Vladimir Uflyand, Bulat Okudzhava, Sergei Dovlatov. In 1959-60 he became close friends with the young poets who had previously belonged to the “industrial committee” - a literary association at the Palace of Culture of the Industrial Cooperation (later the Leningrad City Council).

On February 14, 1960, the first major public performance took place at the “tournament of poets” in the Leningrad Gorky Palace of Culture with the participation of A. S. Kushner, G. Ya. Gorbovsky, V. A. Sosnora. The reading of the poem “Jewish Cemetery” caused a scandal.

During a trip to Samarkand in December 1960, Brodsky and his friend, former pilot Oleg Shakhmatov, considered a plan to hijack a plane in order to fly abroad. But they did not dare to do this. Shakhmatov was later arrested for illegal possession of weapons and reported to the KGB about this plan, as well as about another friend of his, Alexander Umansky, and his “anti-Soviet” manuscript, which Shakhmatov and Brodsky tried to give to an American they met by chance. On January 29, 1961, Brodsky was detained by the KGB, but two days later he was released.

At the turn of 1960-61, Brodsky gained fame on the Leningrad literary scene. According to David Shrayer-Petrov: “In April 1961, I returned from the army. Ilya Averbakh, whom I met on Nevsky Prospekt, said: “The brilliant poet Joseph Brodsky appeared in Leningrad. He is only twenty-one years old. He really writes for one year. It was opened by Zhenya Rein." In August 1961, in Komarov, Evgeniy Rein introduces Brodsky to Anna Akhmatova. In 1962, during a trip to Pskov, he met N.Ya. Mandelstam, and in 1963, at Akhmatova’s, with Lydia Chukovskaya. After Akhmatova’s death in 1966, with the light hand of D. Bobyshev, four young poets, including Brodsky, were often referred to in memoirs as “Akhmatova’s orphans.”

In 1962, twenty-two-year-old Brodsky met the young artist Marina (Marianna) Basmanova, daughter of the artist P.I. Basmanov. From that time on, Marianna Basmanova, hidden under the initials “M. B.”, many of the poet’s works were dedicated.

“Poems dedicated to “M. B.“, occupy a central place in Brodsky’s lyrics not because they are the best - among them there are masterpieces and there are passable poems - but because these poems and the spiritual experience invested in them were the crucible in which his poetic personality was melted.” .

The first poems with this dedication - “I hugged these shoulders and looked ...”, “No longing, no love, no sadness ...”, “A riddle to an angel” - date back to 1962. The collection of poems by I. Brodsky “New Stanzas for Augusta” (USA, Michigan: Ardis, 1983) is compiled from his poems of 1962-1982, dedicated to “M. B." The last poem with dedication “M. B." dated 1989.

On October 8, 1967, Marianna Basmanova and Joseph Brodsky had a son, Andrei Osipovich Basmanov. In 1972-1995. M.P. Basmanova and I.A. Brodsky were in correspondence.

Early poems, influences

According to his own words, Brodsky began writing poetry at the age of eighteen, but there are several poems dating from 1956-1957. One of the decisive impetuses was the acquaintance with the poetry of Boris Slutsky. “Pilgrims”, “Monument to Pushkin”, “Christmas Romance” are the most famous of Brodsky’s early poems. Many of them are characterized by pronounced musicality. Thus, in the poems “From the outskirts to the center” and “I am the son of the suburbs, the son of the suburbs, the son of the suburbs...” you can see the rhythmic elements of jazz improvisations. Tsvetaeva and Baratynsky, and a few years later Mandelstam, had, according to Brodsky himself, a decisive influence on him.

Among his contemporaries he was influenced by Evgeny Rein, Vladimir Uflyand, Stanislav Krasovitsky.

Later, Brodsky called Auden and Tsvetaeva the greatest poets, followed by Cavafy and Frost, and Rilke, Pasternak, Mandelstam and Akhmatova closed the poet’s personal canon.

Persecution, trial and exile

It was obvious that the article was a signal for persecution and, possibly, the arrest of Brodsky. However, according to Brodsky, more than the slander, the subsequent arrest, trial and sentence, his thoughts were occupied at that time by the break with Marianna Basmanova. During this period there was a suicide attempt.

On January 8, 1964, Vecherny Leningrad published a selection of letters from readers demanding that the “parasite Brodsky” be punished. On January 13, 1964, Brodsky was arrested on charges of parasitism. On February 14, he had his first heart attack in his cell. From that time on, Brodsky constantly suffered from angina pectoris, which always reminded him of a possible imminent death (which, however, did not prevent him from remaining a heavy smoker). This is largely where “Hello, my aging!” at 33 years old and “What can I say about life? What turned out to be a long time” at 40, with his diagnosis, the poet really wasn’t sure that he would live to see this birthday.

On February 18, 1964, the court decided to send Brodsky for a compulsory forensic psychiatric examination. Brodsky spent three weeks at “Pryazhka” (psychiatric hospital No. 2 in Leningrad) and subsequently noted: “... it was the worst time in my life.” According to Brodsky, in a psychiatric hospital they used a trick on him: “They woke him up in the dead of night, immersed him in an ice bath, wrapped him in a wet sheet and placed him next to the radiator. From the heat of the radiators, the sheet dried out and cut into the body.” The examination conclusion read: “He has psychopathic character traits, but is able to work. Therefore, administrative measures may be applied.” After this, a second court hearing took place.

Two sessions of the trial of Brodsky (judge of the Dzerzhinsky court Savelyeva E.A.) were noted by Frida Vigdorova and were widely disseminated in samizdat.

Judge: What is your work experience?

Brodsky: About...

Judge: We are not interested in “approximately”!

Brodsky: Five years.

Judge: Where did you work?

Brodsky: At the factory. In geological parties...

Judge: How long did you work at the plant?

Brodsky: Year.

Judge: By whom?

Brodsky: Milling machine operator.

Judge: In general, what is your specialty?

Brodsky: Poet, poet-translator.

Judge: Who admitted that you are a poet? Who classified you as a poet?

Brodsky: Nobody. (No call). And who ranked me among the human race?

Judge: Did you study this?

Brodsky: To what?

Judge: To be a poet? Didn’t try to graduate from a university where they prepare... where they teach...

Brodsky: I didn’t think... I didn’t think that this was given by education.

Judge: And with what?

Brodsky: I think this... (confused) from God...

Judge: Do you have any petitions to the court?

Brodsky: I would like to know: why was I arrested?

Judge: This is a question, not a motion.

Brodsky: Then I have no petition.

Brodsky’s lawyer said in her speech: “None of the prosecution witnesses know Brodsky, have not read his poems; prosecution witnesses testify on the basis of some incomprehensibly obtained and unverified documents and express their opinions by making accusatory speeches.”

On March 13, 1964, at the second court hearing, Brodsky was sentenced to the maximum possible punishment under the Decree on “parasitism” - five years of forced labor in a remote area. He was exiled (transported under escort along with criminal prisoners) to the Konoshsky district of the Arkhangelsk region and settled in the village of Norinskaya. In an interview with Volkov, Brodsky called this time the happiest in his life. In exile, Brodsky studied English poetry, including the work of Winston Auden:

I remember sitting in a small hut, looking through a square window the size of a porthole at a wet, muddy road with chickens roaming along it, half believing what I had just read... I simply refused to believe that back in 1939 English the poet said: “Time... worships language,” but the world remained the same.

- “Bow to the Shadow”

Along with extensive poetic publications in emigrant publications (“Airways”, “New Russian Word”, “Posev”, “Grani”, etc.), in August and September 1965, two of Brodsky’s poems were published in the Konosha regional newspaper “Prazyv” .

The trial of the poet became one of the factors that led to the emergence of the human rights movement in the USSR and to increased attention abroad to the situation in the field of human rights in the USSR. The recording of the trial, made by Frida Vigdorova, was published in influential foreign publications: “New Leader”, “Encounter”, “Figaro Litteraire”, and was read on the BBC. With the active participation of Akhmatova, a public campaign was conducted in defense of Brodsky. The central figures in it were Frida Vigdorova and Lydia Chukovskaya. For a year and a half, they tirelessly wrote letters in defense of Brodsky to all party and judicial authorities and attracted people who had influence in the Soviet system to defend Brodsky. Letters in defense of Brodsky were signed by D.D. Shostakovich, S.Ya. Marshak, K.I. Chukovsky, K.G. Paustovsky, A.T. Tvardovsky, Yu.P. German and others. After a year and a half, in September 1965, under pressure from the Soviet and world community (in particular, after an appeal to the Soviet government by Jean-Paul Sartre and a number of other foreign writers), the term of exile was reduced to the time actually served, and Brodsky returned to Leningrad. According to Y. Gordin: “The efforts of the luminaries of Soviet culture did not have any impact on the authorities. Decisive was the warning of “friend of the USSR” Jean-Paul Sartre that at the European Writers’ Forum the Soviet delegation could find itself in a difficult position because of the “Brodsky case.”

Brodsky resisted the image of a fighter against Soviet power imposed on him, especially by the Western media. A. Volgina wrote that Brodsky “did not like to talk in interviews about the hardships he suffered in Soviet psychiatric hospitals and prisons, persistently moving away from the image of a “victim of the regime” to the image of a “self-made man.” In particular, he stated: “I was lucky in every way. Other people got it much more, had it much harder than me.” And even: “... I think that I actually deserve all this.” In “Dialogues with Joseph Brodsky” by Solomon Volkov, Brodsky says about Frida Vigdorova’s recording of the trial: “It’s not all that interesting, Solomon. Trust me,” to which Volkov expresses his indignation:

SV: You assess it so calmly now, in hindsight! And, forgive me, this trivializes a significant and dramatic event. For what?

IB: No, I’m not making this up! I say this the way I really think! And then I thought the same. I refuse to dramatize any of this!

Last years at home

Brodsky was arrested and sent into exile as a 23-year-old youth, and returned as a 25-year-old established poet. He was given less than 7 years to remain in his homeland. Maturity has arrived, the time of belonging to one circle or another has passed. Anna Akhmatova died in March 1966. Even earlier, the “magic choir” of young poets that surrounded her began to disintegrate. Brodsky's position in official Soviet culture during these years can be compared with the position of Akhmatova in the 1920-1930s or Mandelstam in the period preceding his first arrest.

At the end of 1965, Brodsky handed over the manuscript of his book “Winter Mail (poems 1962-1965)” to the Leningrad branch of the publishing house “Soviet Writer”. A year later, after many months of ordeal and despite numerous positive internal reviews, the manuscript was returned by the publisher. “The fate of the book was not decided by the publishing house. At some point, the regional committee and the KGB decided, in principle, to cross out this idea.”

In 1966-1967, 4 poems by the poet appeared in the Soviet press (not counting publications in children's magazines), after which a period of public muteness began. From the reader's point of view, the only area of poetic activity available to Brodsky remained translations. “Such a poet does not exist in the USSR,” declared the Soviet embassy in London in 1968 in response to an invitation sent to Brodsky to take part in the international poetry festival Poetry International.

Meanwhile, these were years filled with intense poetic work, the result of which were poems that were later included in books published in the USA: “Stopping in the Desert,” “The End of a Beautiful Era,” and “New Stanzas for Augusta.” In 1965-1968, work was underway on the poem “Gorbunov and Gorchakov” - a work to which Brodsky himself attached great importance. In addition to infrequent public appearances and readings at friends’ apartments, Brodsky’s poems were distributed quite widely in samizdat (with numerous inevitable distortions; copying equipment did not exist in those years). Perhaps they received a wider audience thanks to songs written by Alexander Mirzayan and Evgeny Klyachkin.

Outwardly, Brodsky’s life during these years was relatively calm, but the KGB did not ignore its “old client”. This was also facilitated by the fact that “the poet is becoming extremely popular with foreign journalists and Slavic scholars who come to Russia. They interview him, invite him to Western universities (naturally, the authorities do not give permission to leave), etc.” In addition to translations - work on which he took very seriously - Brodsky earned extra money in other ways available to a writer excluded from the “system”: as a freelance reviewer for the Aurora magazine, as random “hack jobs” in film studios, and even acted (as the secretary of the city party committee ) in the film "Train to Distant August".

Outside the USSR, Brodsky's poems continue to appear both in Russian and in translation, primarily in English, Polish and Italian. In 1967, an unauthorized collection of translations “Joseph Brodsky. Elegy to John Donne and Other Poems / Tr. by Nicholas Bethell. In 1970, “Stop in the Desert,” Brodsky’s first book compiled under his supervision, was published in New York. Poems and preparatory materials for the book were secretly exported from Russia or, as in the case of the poem “Gorbunov and Gorchakov,” sent to the West by diplomatic mail.

Partially, this book by Brodsky included the first (Poems and Poems, 1965), although at the insistence of the author, twenty-two poems from the earlier book were not included in Stop. But about thirty new pieces were added, written between 1965 and 1969. Stopover in the Desert featured Max Hayward's name as the publisher's editor-in-chief. They considered me to be the actual editor of the book, but we... decided that it was better not to mention my name, since starting in 1968, mainly because of my contacts with Brodsky, the KGB took note of me. I myself believed that Brodsky was the real editor, since it was he who selected what to include in the book, outlined the order of the poems and gave names to the six sections.

George L. Kline. A tale of two books

In 1971, Brodsky was elected a member of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts.

In exile

Departure

The suitcase with which Joseph Brodsky left his homeland forever on June 4, 1972,

The suitcase with which Joseph Brodsky left his homeland forever on June 4, 1972,

taking away a typewriter, two bottles of vodka for W. Hugh Auden and a collection of John Donne's poems.

American office of Joseph Brodsky in the Anna Akhmatova Museum in the Fountain House.

Photo of 2014

On May 10, 1972, Brodsky was summoned to the OVIR and given a choice: immediate emigration or “hot days,” which a metaphor in the mouth of the KGB could mean interrogations, prisons and mental hospitals. By that time, twice already - in the winter of 1964 - he had to undergo “examination” in psychiatric hospitals, which, according to him, was worse than prison and exile. Brodsky decides to leave. Having learned about this, Vladimir Maramzin suggested that he collect everything he had written to prepare a samizdat collection of works. The result was the first and, until 1992, the only collected works of Joseph Brodsky—typewritten, of course. Before leaving, he managed to authorize all 4 volumes. Having chosen to emigrate, Brodsky tried to delay the day of departure, but the authorities wanted to get rid of the unwanted poet as quickly as possible. On June 4, 1972, deprived of Soviet citizenship, Brodsky flew from Leningrad on an “Israeli visa” and along the route prescribed for Jewish emigration - to Vienna. 3 years later he wrote:

Blowing into the hollow pipe that is your fakir,

I walked through the ranks of Janissaries in green,

feeling the cold of their evil axes with your eggs,

like when entering water. And so, with salty

the taste of this water in my mouth,

I crossed the line...

Cape Cod Lullaby (1975)

Brodsky recalled what followed with considerable ease, refusing to dramatize the events of his life:

The plane landed in Vienna, and Karl Proffer met me there... he asked: “Well, Joseph, where would you like to go?” I said, “Oh my God, I have no idea”... and then he said, “How would you like to work at the University of Michigan?”

These words are given a different perspective by the memoirs of Seamus Heaney, who knew Brodsky closely, in his article published a month after the poet’s death:

“Events of 1964-1965. made him something of a celebrity and guaranteed fame at the very moment of his arrival in the West; but instead of taking advantage of his victim status and going with the flow of “radical chic,” Brodsky immediately began work as a teacher at the University of Michigan. Soon his fame was no longer based on what he managed to accomplish in his old homeland, but on what he did in his new one.”

Seamus Heaney. The Singer of Tales: On Joseph Brodsky

Two days after his arrival in Vienna, Brodsky went to meet W. Auden, who lived in Austria. “He treated me with extraordinary sympathy, immediately took me under his wing... undertook to introduce me to literary circles.” Together with Auden, Brodsky took part in at the International Poetry Festival in London. Brodsky was familiar with Auden’s work from the time of his exile and called him, along with Akhmatova, a poet who had a decisive “ethical influence” on him. At the same time in London, Brodsky met Isaiah Berlin, Stephen Spender, Seamus Heaney and Robert Lowell.

Life line

In July 1972 Brodsky moved to the USA and accepted the post of “guest poet” (poet-in-residence) at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he taught, intermittently, until 1980. From that moment on, Brodsky, who completed incomplete 8 grades of high school in the USSR, led the life of a university teacher, holding professorships over the next 24 years in a total of six American and British universities, including Columbia and New York. He taught the history of Russian literature, Russian and world poetry, the theory of verse, and gave lectures and poetry readings at international literary festivals and forums, in libraries and universities in the USA, Canada, England, Ireland, France, Sweden, and Italy.

“Taught” in his case needs clarification. For what he did was little similar to what his university colleagues, including poets, did. First of all, he simply did not know how to “teach.” He had no personal experience in this matter... Every year out of twenty-four, for at least twelve weeks in a row, he regularly appeared before a group of young Americans and talked to them about what he loved most in the world - about poetry... What was the name course, was not so important: all his lessons were lessons in slow reading of a poetic text...

Lev Losev

Over the years, his health steadily deteriorated, and Brodsky, whose first heart attack occurred during his prison days in 1964, suffered four heart attacks in 1976, 1985 and 1994. Here is the testimony of a doctor who visited Brodsky in the first month of Norino exile:

“There was nothing acutely threatening in his heart at that moment, except for mild signs of so-called cardiac muscle dystrophy. However, it would be surprising to see them absent given the way of life he had in this timber industry... Imagine a large field after clearing a taiga forest, on which huge stone boulders are scattered among numerous stumps... Some of these boulders exceed the height of a person. The work consists of rolling such boulders with a partner onto steel sheets and moving them to the road... Three to five years of such exile - and hardly anyone today has heard of the poet... because his genes, unfortunately, were prescribed to have early atherosclerosis heart vessels. But medicine learned to fight this, at least partially, only thirty years later.”

Brodsky’s parents submitted an application twelve times asking for permission to see their son; congressmen and prominent US cultural figures made the same request to the USSR government, but even after Brodsky underwent open-heart surgery in 1978 and needed care, his parents was denied an exit visa. They never saw their son again. Brodsky's mother died in 1983, and his father died a little over a year later. Both times Brodsky was not allowed to come to the funeral. The book “Part of Speech” (1977), the poems “The Thought of You Moves Away, Like a Disgraced Servant...” (1985), “In Memory of the Father: Australia” (1989), and the essay “A Room and a Half” (1985) are dedicated to the parents.

In 1977, Brodsky accepted American citizenship, in 1980 he finally moved from Ann Arbor to New York, and subsequently divided his time between New York and South Hadley (English) Russian, a university town in Massachusetts, where since 1982 for the rest of his life he taught in the spring semesters at the Five Colleges consortium. In 1990, Brodsky married Maria Sozzani, an Italian aristocrat who was Russian on her mother's side. In 1993, their daughter Anna was born.

Poet and essayist

Brodsky's poems and their translations have been published outside the USSR since 1964, when his name became widely known thanks to the publication of a recording of the poet's trial. Since his arrival in the West, his poetry regularly appears on the pages of publications of the Russian emigration. Almost more often than in the Russian-language press, translations of Brodsky’s poems are published, primarily in magazines in the USA and England, and in 1973 a book of selected translations appeared. But new books of poetry in Russian were published only in 1977 - these are “The End of a Beautiful Era,” which included poems from 1964-1971, and “Part of Speech,” which included works written in 1972-1976. The reason for this division was not external events (emigration) - the understanding of exile as a fateful factor was alien to Brodsky's work - but the fact that, in his opinion, in 1971/1972 qualitative changes were taking place in his work. “Still Life”, “To a Tyrant”, “Odysseus to Telemachus”, “Song of Innocence, also known as Experience”, “Letters to a Roman Friend”, “Bobo’s Funeral” are written on this turning point. In the poem “1972,” begun in Russia and completed abroad, Brodsky gives the following formula: “Everything that I did, I did not for the sake of / fame in the era of cinema and radio, / but for the sake of my native speech, literature...”. The title of the collection - “Part of Speech” - is explained by the same message, lapidarily formulated in his Nobel lecture: “everyone, but a poet always knows that it is not language that is his instrument, but he is the means of language.”

In the 1970s and 1980s, Brodsky, as a rule, did not include poems included in earlier collections in his new books. An exception is the book “New Stanzas for Augusta”, published in 1983, composed of poems addressed to M. B. Marina Basmanova. Years later, Brodsky spoke about this book: “This is the main work of my life, it seems to me that in the end “New Stanzas for Augusta” can be read as a separate work. Unfortunately, I did not write The Divine Comedy. And, apparently, I will never write it again. And here it turned out to be a kind of poetic book with its own plot...” “New Stanzas for Augusta” became the only book of Brodsky’s poetry in Russian, compiled by the author himself.

Since 1972, Brodsky has been actively turning to essay writing, which he does not abandon until the end of his life. Three books of his essays are published in the United States: Less Than One in 1986, Watermark in 1992, and On Grief and Reason in 1995. Most of the essays, included in these collections, was written in English. His prose, at least as much as his poetry, made Brodsky's name widely known to the world outside the USSR. The American National Board of Book Critics recognized the collection “Less Than One” as the best literary critical book in the United States for 1986. By this time, Brodsky was the owner of half a dozen titles of member of literary academies and honorary doctorates from various universities, and was the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship in 1981.

The next large book of poems, “Urania,” was published in 1987. In the same year, Brodsky won the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was awarded to him “for an all-embracing authorship, imbued with clarity of thought and poetic intensity.” The 47-year-old Brodsky began his Nobel speech, written in Russian, in which he formulated a personal and poetic credo:

“For a private person who has preferred this particularity all his life to some public role, for a person who has gone quite far in this preference - and in particular from his homeland, for it is better to be the last loser in a democracy than a martyr or ruler of thoughts in a despotism - to find himself suddenly on this podium there is great awkwardness and testing.”

In the 1990s, four books of new poems by Brodsky were published: “Notes of a Fern,” “Cappadocia,” “In the Vicinity of Atlantis,” and the collection “Landscape with a Flood,” published in Ardis after the poet’s death and which became the final collection.

The undoubted success of Brodsky's poetry both among critics and literary critics, and among readers, probably has more exceptions than would be required to confirm the rule. The reduced emotionality, musical and metaphysical complexity - especially of the “late” Brodsky - also repel some artists. In particular, one can name the work of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, whose reproaches to the poet’s work are largely ideological in nature. He is echoed almost verbatim by a critic from another camp: Dmitry Bykov in his essay about Brodsky after the opening: “I’m not going to repeat here the common platitudes that Brodsky is ‘cold’, ‘monotonous’, ‘inhuman’...”, further does just that: “In the huge corpus of Brodsky’s works there are strikingly few living texts... It is unlikely that today’s reader will finish reading “Procession”, “Farewell, Mademoiselle Veronica” or “Letter in a Bottle” without effort - although, undoubtedly, he cannot help but appreciate “Part speeches", "Twenty Sonnets to Mary Stuart" or "Conversation with a Celestial": the best texts of the still living, not yet petrified Brodsky, the cry of a living soul, feeling its ossification, glaciation, dying."

The last book, compiled during the poet’s lifetime, ends with the following lines:

And if you don’t expect thanks for the speed of light,

then the general, maybe, armor of non-existence

appreciates attempts to turn it into a sieve

and will thank me for the hole.

- “I was reproached for everything except the weather...”

Playwright, translator, writer

Brodsky wrote two published plays: “Marble”, 1982 and “Democracy”, 1990-1992. He also translated the plays of the English playwright Tom Stoppard “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead” and the Irishman Brendan Behan “Speaking of Rope.” Brodsky left a significant legacy as a translator of world poetry into Russian. Among the authors he translated, we can name, in particular, John Donne, Andrew Marvell, Richard Wilbur, Euripides (from Medea), Konstantinos Cavafy, Constant Ildefons Galczynski, Czeslaw Milosz, Thomas Wenclow. Brodsky turned to translations into English much less often. First of all, these are, of course, self-translations, as well as translations from Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva, Wislawa Szymborska and a number of others.

Susan Sontag, an American writer and close friend of Brodsky, says: “I am sure that he saw his exile as the greatest opportunity to become not only a Russian, but a world poet... I remember Brodsky saying, laughing, somewhere in 1976-1977: “Sometimes it’s so strange for me to think that I can write whatever I want, and it will be published." Brodsky took full advantage of this opportunity. Since 1972, he has plunged headlong into social and literary life. In addition to the three above-mentioned books, essays , the number of articles, prefaces, letters to the editor, reviews of various collections written by him exceeds one hundred, not counting numerous oral presentations at evenings of creativity of Russian and English-language poets, participation in discussions and forums, magazine interviews. In the list of authors whose work he gives a review, the names of I. Lisnyanskaya, E. Rein, A. Kushner, D. Novikov, B. Akhmadulina, L. Losev, Y. Kublanovsky, Y. Aleshkovsky, V. Uflyand, V. Gandelsman, A. Naiman, R. Derieva, R. Wilber, C. Milos, M. Strand, D. Walcott and others. The largest newspapers in the world publish his appeals in defense of persecuted writers: S. Rushdie, N. Gorbanevskaya, V. Maramzin, T. Ventslov, K. Azadovsky. “In addition, he tried to help so many people,” including through letters of recommendation, “that recently there has been a certain devaluation of his recommendations.”

Relative financial well-being (at least by emigration standards) gave Brodsky the opportunity to provide more material assistance. Lev Losev writes:

Several times I participated in collecting money to help needy old acquaintances, sometimes even those for whom Joseph should not have sympathy, and when I asked him, he began to hastily write out a check, not even allowing me to finish.

Here is the testimony of Roman Kaplan, who knew Brodsky since Russian times, the owner of the Russian Samovar restaurant, one of the cultural centers of Russian emigration in New York:

In 1987, Joseph received the Nobel Prize... I had known Brodsky for a long time and turned to him for help. Joseph and Misha Baryshnikov decided to help me. They contributed money, and I gave them some share of this restaurant... Alas, I did not pay dividends, but I solemnly celebrated his birthday every year.

The Library of Congress elects Brodsky as Poet Laureate of the United States for 1991-1992. In this honorable, but traditionally nominal capacity, he developed active efforts to promote poetry. His ideas led to the creation of the American Poetry and Literacy Project, which since 1993 has distributed more than a million free poetry books to schools, hotels, supermarkets, train stations, and more. According to William Wadsworth, who served from 1989 to 2001. post of director of the American Academy of Poets, Brodsky’s inaugural speech as Poet Laureate “caused a transformation in America’s view of the role of poetry in its culture.” Shortly before his death, Brodsky became interested in the idea of founding a Russian Academy in Rome. In the fall of 1995, he approached the mayor of Rome with a proposal to create an academy where artists, writers and scientists from Russia could study and work. This idea was realized after the poet's death. In 2000, the Joseph Brodsky Scholarship Fund sent the first Russian poet-scholar to Rome, and in 2003, the first artist.

English-language poet

In 1973 The first authorized book of translations of Brodsky's poetry into English is published - "Selected poems" (Selected poems) translated by George Cline and with a foreword by Auden. The second collection in English, A Part of Speech, was published in 1980; the third, “To Urania” (To Urania), - in 1988. In 1996, “So Forth” (So on) was published - the 4th collection of poems in English, prepared by Brodsky. The last two books included both translations and auto-translations from Russian, as well as poems written in English. Over the years, Brodsky trusted other translators less and less to translate his poems into English; at the same time, he increasingly wrote poetry in English, although, in his own words, he did not consider himself a bilingual poet and argued that “for me, when I write poetry in English, it’s more of a game...”. Losev writes: “Linguistically and culturally, Brodsky was Russian, and as for self-identification, in his mature years he reduced it to a lapidary formula, which he repeatedly used: “I am a Jew, a Russian poet and an American citizen.”

In the five-hundred-page collection of Brodsky's English-language poetry, published after the author's death, there are no translations made without his participation. But if his essayism evoked mostly positive critical responses, the attitude towards him as a poet in the English-speaking world was far from unambiguous. According to Valentina Polukhina, “The paradox of Brodsky’s perception in England is that with the growth of Brodsky’s reputation as an essayist, attacks on Brodsky the poet and translator of his own poems intensified.” The range of assessments was very wide, from extremely negative to laudatory, and a critical bias probably prevailed. The role of Brodsky in English-language poetry, the translation of his poetry into English, and the relationship between the Russian and English languages in his work are discussed, in particular, in Daniel Weissbort’s essay-memoir “From Russian with love.” He has the following assessment of Brodsky’s English poems:

In my opinion, they are very helpless, even outrageous, in the sense that he introduces rhymes that are not taken seriously in a serious context. He tried to expand the boundaries of the use of female rhyme in English poetry, but as a result his works began to sound like W. S. Gilbert or Ogden Nash. But gradually he got better and better, and he really began to expand the possibilities of English prosody, which in itself is an extraordinary achievement for one person. I don't know who else could have achieved this. Nabokov couldn't.

Return

Perestroika in the USSR and the concurrent awarding of the Nobel Prize to Brodsky broke the dam of silence in his homeland, and soon the publication of Brodsky’s poems and essays began to pour in. The first (besides several poems leaked to print in the 1960s) selection of Brodsky’s poems appeared in the December 1987 issue of Novy Mir. Until this moment, the poet’s work was known in his homeland to a very limited circle of readers thanks to lists of poems distributed in samizdat. In 1989, Brodsky was rehabilitated following the 1964 trial.

In 1992, a 4-volume collected works began to be published in Russia. In 1995, Brodsky was awarded the title of honorary citizen of St. Petersburg. Invitations to return to their homeland followed. Brodsky postponed his visit: he was embarrassed by the publicity of such an event, the celebration, and the media attention that would inevitably accompany his visit. My health didn’t allow it either. One of the last arguments was: “The best part of me is already there - my poems.”

Death and burial

On Saturday evening, January 27, 1996, in New York City, Brodsky was preparing to travel to South Hadley and packed a briefcase with manuscripts and books to take with him the next day. The spring semester began on Monday. Having wished his wife good night, Brodsky said that he still needed to work, and went up to his office. In the morning, on the floor in the office, his wife discovered him. Brodsky was fully dressed. On the desk next to the glasses lay an open book - a bilingual edition of Greek epigrams.

Joseph Aleksandrovich Brodsky died suddenly on the night of January 27-28, 1996, 4 months before his 56th birthday. The cause of death was sudden cardiac arrest due to a heart attack.

On February 1, 1996, a funeral service was held at the Grace Episcopal Parish Church in Brooklyn Heights, not far from Brodsky's home. The next day, a temporary burial took place: the body in a coffin lined with metal was placed in a crypt in the cemetery at the Trinity Church Cemetery, on the banks of the Hudson, where it was kept until June 21, 1997. The proposal sent by telegram from the deputy of the State Duma of the Russian Federation G.V. Starovoytova to bury the poet in St. Petersburg on Vasilyevsky Island was rejected - “this would mean deciding for Brodsky the issue of returning to his homeland.” A memorial service was held on March 8 in Manhattan at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist. There were no speeches. Poems were read by Czeslaw Milosz, Derek Walcott, Seamus Heaney, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Lev Losev, Anthony Hecht, Mark Strand, Rosanna Warren, Evgeniy Rein, Vladimir Uflyand, Thomas Venclova, Anatoly Naiman, Yakov Gordin, Maria Sozzani-Brodskaya and others. The music of Haydn, Mozart, and Purcell was played. In 1973, in the same cathedral, Brodsky was one of the organizers of the memorial service in memory of Wisten Auden.

In his widely quoted memoirs dedicated to Brodsky's last will and funeral, the poet and translator Ilya Kutik says:

Two weeks before his death, Brodsky bought himself a place in a small chapel in a New York cemetery next to Broadway (this was his last will). After this, he drew up a fairly detailed will. A list was also compiled of people to whom letters were sent, in which Brodsky asked the recipient of the letter to sign that until 2020 the recipient would not talk about Brodsky as a person and would not discuss his private life; it was not forbidden to talk about Brodsky the poet.

Most of the claims made by Kutik are not supported by other sources. At the same time, E. Shellberg, M. Vorobyova, L. Losev, V. Polukhina, T. Ventslova, who knew Brodsky closely, issued refutations. In particular, Shellberg and Vorobyova stated: “We would like to assure you that the article about Joseph Brodsky, published under the name of Ilya Kutik on page 16 of Nezavisimaya Gazeta dated January 28, 1998, is 95 percent fiction.” Lev Losev expressed his sharp disagreement with Kutik’s story, who testified, among other things, that Brodsky did not leave instructions regarding his funeral; I didn’t buy a place in the cemetery, etc. According to the testimony of Losev and Polukhina, Ilya Kutik was not present at the funeral of Brodsky that he described.

The decision on the final resting place of the poet took more than a year. According to Brodsky’s widow Maria: “The idea of a funeral in Venice was suggested by one of his friends. This is the city that, apart from St. Petersburg, Joseph loved most. Besides, selfishly speaking, Italy is my country, so it was better that my husband was buried there. It was easier to bury him in Venice than in other cities, for example in my hometown of Compignano near Lucca. Venice is closer to Russia and is a more accessible city.” Veronica Schilz and Benedetta Craveri agreed with the Venetian authorities about a place in the ancient cemetery on the island of San Michele. The desire to be buried on San Michele is found in Brodsky’s 1974 comic message to Andrei Sergeev:

Although the unconscious body

equally decay everywhere,

devoid of native clay, it is in the alluvium of the valley

Lombard rot is not averse. Ponezhe

its continent and the same worms.

Stravinsky sleeps on San Michele...

On June 21, 1997, the reburial of the body of Joseph Brodsky took place at the San Michele cemetery in Venice. Initially, it was planned to bury the poet’s body in the Russian half of the cemetery between the graves of Stravinsky and Diaghilev, but this turned out to be impossible, since Brodsky was not Orthodox. The Catholic clergy also refused burial. As a result, they decided to bury the body in the Protestant part of the cemetery. The resting place was marked by a modest wooden cross with the name Joseph Brodsky A few years later, a tombstone by the artist Vladimir Radunsky was erected at the poet’s grave.

On the back of the monument there is an inscription in Latin - a line from the elegy Propertius Latin. Letum non omnia finit- Not everything ends with death.

When people come to the grave, they leave stones, letters, poems, pencils, photographs, Camel cigarettes (Brodsky smoked a lot) and whiskey.

Family

- Mother - Maria Moiseevna Volpert (1905-1983)

- Father - Alexander Ivanovich Brodsky (1903-1984)

- Son - Andrey Osipovich Basmanov (born 1967), from Marianna Basmanova.

- Daughter - Anastasia Iosifovna Kuznetsova (born 1972), from ballerina Maria Kuznetsova.

- Wife (since 1990) - Maria Sozzani (born 1969).

- Daughter - Anna Alexandra Maria Brodskaya (born 1993).

Addresses in St. Petersburg

- 1955-1972 - apartment building of A.D. Muruzi - Liteiny Prospekt, building 24, apt. 28. The administration of St. Petersburg plans to buy the rooms where the poet lived and open a museum there. Exhibits of the future museum can be temporarily seen in the exhibition of the Anna Akhmatova Museum in the Fountain House.

- 1962-1972- Mansion of N.L. Benois - Glinka Street, building 15. Apartment of Marianna Basmanova.

In Komarov

- August 7, 1961 - in “Budka”, in Komarov, E.B. Rein introduces Brodsky to A.A. Akhmatova.

- At the beginning of October 1961, I went to Akhmatova in Komarovo together with S. Schultz.

- June 24, 1962 - on Akhmatova’s birthday, he wrote two poems “A.A. Akhmatova” (“The roosters will crow and crow ...”) from where she took the epigraph “You will write about us obliquely” for the poem “The Last Rose”, as well as “For churches, gardens, theaters..." and a letter. In the same year he dedicated other poems to Akhmatova. Morning mail for Akhmatova from the city of Sestroretsk (“In the bushes of immortal Finland...”).

- Autumn and winter 1962-1963 - Brodsky lives in Komarov, at the dacha of the famous biologist R.L. Berg, where he works on the cycle “Songs of a Happy Winter”. Close communication with Akhmatova. Meeting Academician V.M. Zhirmunsky.

- October 5, 1963 - in Komarov, “Here I am again hosting the parade...”.

- May 14, 1965 - visits Akhmatova in Komarov.

For two days he sat opposite me on the chair on which you are now sitting... After all, our troubles are not without reason - where has this been seen, where has this been heard, that a criminal would be released from exile for a few days to stay in his hometown?.. Inseparable from his former one lady. Very good-looking. You can fall in love! Slender, ruddy, skin like a five-year-old girl... But, of course, he won’t survive this winter in exile. Heart disease is no joke.

- March 5, 1966 - death of A.A. Akhmatova. Brodsky and Mikhail Ardov spent a long time looking for a place for Akhmatova’s grave, first in the cemetery in Pavlovsk at the request of Irina Punina, then in Komarov on their own initiative.

She just taught us a lot. Humility, for example. I think... that in many ways I owe my best human qualities to her. If not for her, it would have taken them longer to develop, if they had appeared at all.

Heritage

According to Andrei Ranchin, professor at the Department of History of Russian Literature at Moscow State University, “Brodsky is the only modern Russian poet who has already been awarded the honorary title of classic. Brodsky's literary canonization is an exceptional phenomenon. No other modern Russian writer has been honored to become the hero of so many memoir texts; so many conferences have never been dedicated to anyone.”

With regard to Brodsky’s creative heritage, the following can be confidently stated today: at the moment, all editions of Brodsky’s works and archival documents are controlled, in accordance with his will, by the Joseph Brodsky Estate Fund, headed by his assistant (since 1986) Anne Schellberg, whom Brodsky appointed as his literary executor, and his widow Maria Sozzani-Brodskaya. In 2010, Anne Schellberg summarized the situation with the publication of Brodsky's works in Russia:

The foundation cooperates exclusively with the Azbuka publishing group, and today we do not intend to publish Brodsky’s collections with commentaries in competing publishing houses. An exception is made only for the “Poet's Library” series, in which a book with comments by Lev Losev will be published. Pending a future academic meeting, this book will fill the empty space of the available annotated edition

Shortly before his death, Brodsky wrote a letter to the manuscript department of the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg (where the poet's archives until 1972 are mainly stored), in which he asked that access to his diaries, letters and family documents be closed for 50 years. The ban does not apply to manuscripts and other similar materials, and the literary part of the St. Petersburg archive is open to researchers. Another archive, mainly from the poet's American period, is freely available (including most of the correspondence and drafts) at the Beinecke Library, Yale University, USA. The third most important archive (the so-called “Lithuanian”) was acquired by Stanford University in 2013 from the Katilius family, friends of Brodsky. For full or partial publication of any archival documents, permission from the Estate Fund is required. The poet's widow says:

Joseph's instructions cover two areas. First, he requested that his personal and family papers be sealed in the archives for fifty years. Secondly, in the letter attached to the will, as well as in conversations with me about how these issues should be resolved after his death, he asked not to publish his letters and unpublished works. But, as far as I understand, his request allows for the publication of individual quotations from unpublished items for scientific purposes, as is customary in such cases. In the same letter, he asked his friends and family not to take part in writing his biographies.

It is worth mentioning the opinion of Valentina Polukhina, a researcher of Brodsky’s life and work, that at the request of the Inherited Property Fund, “writing a biography is prohibited until 2071...” - that is, for 75 years from the date of the poet’s death, “all Brodsky’s letters, diaries, drafts, and so on are closed... " On the other hand, E. Schellberg states that there is no additional prohibition, apart from the above-mentioned letter from Brodsky to the Russian National Library, and access to drafts and preparatory materials has always been open to researchers. Lev Losev, who wrote the only literary biography of Brodsky to date, was of the same opinion.

Brodsky’s position regarding his future biographers is commented on by the words from his letter:

“I have no objection to philological studies related to my art. works - they are, as they say, the property of the public. But my life, my physical condition, with God’s help belonged and belongs only to me... What seems to me the worst thing in this undertaking is that such works serve the same purpose as the events described in them: that they degrade literature to the level of political reality. Willingly or unwittingly (I hope unwittingly) you simplify for the reader the idea of my mercy. You, forgive the harshness of the tone, are robbing the reader (as well as the author). “Ah,” the Frenchman from Bordeaux will say, “everything is clear.” Dissident. For this, these anti-Soviet Swedes gave him the Nobel. And he won’t buy “Poems”... I don’t care about myself, I feel sorry for him.”

Ya. Gordin. The Knight and Death, or Life as a Plan: About the Fate of Joseph Brodsky. M.: Vremya, 2010

Among the posthumous editions of Brodsky’s works, one should mention the book of poems “Landscape with Flood”, prepared during the author’s lifetime, ed. Alexander Sumerkin, translator of Brodsky’s prose and poetry into Russian, with whose participation most of the poet’s Ardis collections were published. In 2000, the republication of these collections was undertaken by the Pushkin Foundation. In the same publishing house in 1997-2001. "The Works of Joseph Brodsky: 7 volumes" was published. Brodsky's children's poetry in Russian is collected under one cover for the first time in the book “Elephant and Maruska”. The English children's poem Discovery was published with illustrations by V. Radunsky in Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1999. Brodsky the translator is most fully represented in the book “Expulsion from Paradise,” which includes, among other things, previously unpublished translations. In 2000, New York's Farrar, Straus & Giroux published a collection of English-language poetry by Brodsky and his poems translated (largely by the author himself) into English: “Collected Poems in English, 1972-1999.” Translations of Brodsky's English-language poems into Russian were undertaken, in particular, by Andrei Olear and Victor Kulle. According to A. Olear, he managed to discover more than 50 unknown English-language poems by Brodsky in the Beinecke archive. Neither these poems nor their translations have been published to date.

Lev Losev is the compiler and author of the notes of the commented edition of Brodsky’s Russian-language poetry, published in 2011: “Poems and Poems: In 2 volumes,” which includes both the full texts of the six books published by Ardis, compiled during the poet’s lifetime, and some poems not included in them, as well as a number of translations, poems for children, etc. The fate of the academic edition of Brodsky’s works mentioned in print is currently unknown. According to Valentina Polukhina, it is unlikely to appear before 2071. In 2010, E. Shellberg wrote that “at present, textual research at the Russian National Library as part of the preparation of the first volumes of a scientific publication is carried out by philologist Denis Nikolaevich Akhapkin. His work is also supported by the American Council for International Education." A significant body of Brodsky’s Russian-language literary heritage is freely available on the Internet, in particular on the websites Maxim Moshkov Library and Poetry Library. It is difficult to judge the textual reliability of these sites.

Currently, the Joseph Brodsky Literary Museum Foundation operates in St. Petersburg, founded with the goal of opening a museum in the poet’s former apartment on Pestel Street. The temporary exhibition “The American Study of Joseph Brodsky,” including items from the poet’s home in South Hadley, is located at the Anna Akhmatova Museum in the Fountain House in St. Petersburg.

Editions

in Russian

- Poems and poems. - Washington; New York: Inter-Language Literary Associates, 1965.

- Stopping in the desert / preface. N.N. (A. Naiman). - New York: Publishing house named after. Chekhov, 1970.- 2nd ed., revised: Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1988

- The end of a beautiful era: Poems 1964-1971. - Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1977. - Russian edition: St. Petersburg: Pushkin Foundation, 2000

- Part of speech: Poems 1972-1976.- Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1977.- Russian edition: St. Petersburg: Pushkin Foundation, 2000

- Roman Elegies. - New York: Russica Publishers, 1982.

- New stanzas for Augusta (Poems for M.B., 1962-1982). - Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1983. - Ros. ed.: St. Petersburg: Pushkin Foundation, 2000.

- Marble. - Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1984.

- Urania. - Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1987. - 2nd ed., revised: Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1989.

- Fern notes. - Bromma (Sweden): Hylaea, 1990.

- Joseph Brodsky, original size: [Collection dedicated to the 50th anniversary of I. Brodsky] / comp. G. F. Komarov. - L.; Tallinn: Publishing house of the Tallinn center of the Moscow headquarters of MADPR, 1990.

- Poems / comp. J. Gordin. - Tallinn: Eesti raamat; Alexandra, 1991.

- Cappadocia. Poems. - St. Petersburg: Supplement to the almanac Petropol, 1993.

- In the vicinity of Atlantis. New poems. - St. Petersburg: Pushkin Foundation, 1995.

- Landscape with flood. - Dana Point: Ardis, 1996. - Russian edition. (corrections and additions): St. Petersburg: Pushkin Foundation, 2000

- Works of Joseph Brodsky: In 4 volumes / comp. G. F. Komarov. - St. Petersburg: Pushkin Foundation, 1992-1995.

- Works of Joseph Brodsky: In 7 volumes / ed. Ya. Gordin. - St. Petersburg: Pushkin Foundation, 1997-2001.

- Expulsion from Paradise: Selected Translations / ed. Ya. Klots. - St. Petersburg: Azbuka, 2010.

- Poems and poems: In 2 volumes / comp. and note. L. Loseva. - St. Petersburg: Pushkin House, 2011.

- Elephant and Maruska / ill. I. Ganzenko. - St. Petersburg: Azbuka, 2011.

in English

- Joseph Brodsky. Selected poems.- New York: Harper & Row, 1973.

- Joseph Brodsky. A Part of Speech. - New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1980.

- Joseph Brodsky. Less Than One: Selected Essays. - New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1986.

- Joseph Brodsky. To Urania.- New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1988.

- Joseph Brodsky. Marbles: a Play in Three Acts / translated by Alan Myers with Joseph Brodsky. - New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1989.

- Joseph Brodsky. Watermark.- New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; London: Hamish Hamilton, 1992.

- Joseph Brodsky. On Grief and Reason: Essays. - New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1995.

- Joseph Brodsky. So Forth: Poems. - New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1996.

- Joseph Brodsky. Collected Poems in English, 1972-1999 / edited by Ann Kjellberg. - New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000.

- Joseph Brodsky. Nativity Poems / Bilingual Edition. - New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2001.

Radio plays and literary readings

- 1988 - Joseph Brodsky - Stop in the Desert (Melodiya Publishing House)

- 1996- Joseph Brodsky. Early poems (Sintez publishing house)

- 2001- Joseph Brodsky. From nowhere with love (publishing house "Stradiz-Audiobook")

- 2003- Joseph Brodsky. Poems (State Literary Museum Publishing House)

- 2004- My love, Odessa (Melodiya publishing house)

- 2007- Joseph Brodsky. Space of language (publishing house "Stradiz-Audiobook")

- 2008- Classics and contemporaries. Poems and poems. Part 6 (Radio Culture Publishing House)

- 2009- Joseph Brodsky. The Sound of Speech (Citizen K Publishing)

Memory

- In 1998, the Pushkin Foundation published a book of poems by L. Losev, “Afterword,” the first part of which consists of poems related to the memory of Brodsky.

- In 2003, the I. Brodsky Estate Fund and the poet's widow Maria Brodskaya (nee Sozzani) transferred items from Brodsky's house in South Hadley to Russia to create a museum in his homeland. A library, photographs of people dear to Brodsky, furniture reminiscent of what was in his parents' house (desk, secretary, armchair, sofa), table lamp, posters related to Italian trips, a collection of postcards are in the American office of Joseph Brodsky in the Fountain House .

- In 2004, Brodsky's close friend, Nobel Prize-winning poet Derek Walcott, wrote a poem, "The Prodigal", in which Brodsky is mentioned numerous times.

- Since 2004, the Konosha Central District Library has been named after Brodsky, of which the poet was a reader during his period of exile.

- In November 2005, in the courtyard of the Faculty of Philology of St. Petersburg University, according to the design of Konstantin Simun, the first monument to Joseph Brodsky in Russia was erected.

- Konstantin Meladze, Elena Frolova, Evgeny Klyachkin, Alexander Mirzayan, Alexander Vasiliev, Svetlana Surganova, Diana Arbenina, Pyotr Mamonov, Victoria Polevaya, Leonid Margolin and other authors wrote songs based on the poems of I.A. Brodsky.

- On May 21, 2009, a memorial plaque in honor of the poet Joseph Brodsky by sculptor Georgy Frangulyan was unveiled on the “Promenade of the Incurable” in Venice.

- In Moscow, on Novinsky Boulevard in 2011, a monument to the poet was erected by sculptor Georgy Frangulyan and architect Sergei Skuratov.

- The poem “From Nowhere with Love” is included in the title of the film “From Nowhere with Love, or Merry Funeral,” a film adaptation of Lyudmila Ulitskaya’s story “Merry Funeral.” The film features the ballad “From Nowhere with Love” performed by Gennady Trofimov.

- In 2009, the film “One and a Half Rooms, or a Sentimental Journey to the Homeland”, directed by Andrei Khrzhanovsky, was released, based on the works and biography of Joseph Brodsky. The poet was performed by Evgeny Oganjanyan in childhood, by Artyom Smola in his youth, and by Grigory Dityatkovsky in adulthood.

- Name "I. Brodsky" carries an A330 aircraft (tail number VQ-BBE) of Aeroflot.

- In the fall of 2011, the United States Postal Service unveiled stamp designs dedicated to the great American poets of the 20th century, planned for release in 2012. Among them are Joseph Brodsky, Gwendolyn Brooks, William Carlos Williams, Robert Haydn, Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bishop, Wallace Stevens, Denise Levertov, Edward Estlin Cummings and Theodore Roethke. On the reverse side of the stamp sheet are quotes from the works of each poet. The stamp features a photograph of Joseph Brodsky taken in New York by American photographer Nancy Crampton.

- Song by Andrei Makarevich “In Memory of Joseph Brodsky”.

- On December 1, 2011, in the courtyard of house No. 19 on Stakhanovtsev Street in St. Petersburg, a memorial sign to Joseph Brodsky was erected in the form of a huge boulder from Karelia, on which lines from the poem “From the Outskirts to the Center” are carved: “So I again ran through Malaya Okhta a thousand arches."

- On April 8, 2015, a museum opened in a restored hut in the village of Norinskaya, where Brodsky lived in exile.

- In May 2015, V.P. Polukhina’s book “Of those who have not forgotten me” was published. Joseph Brodsky. In memoriam" is an anthology of poetic and prose dedications to the poet, written by almost two hundred domestic and foreign authors.

Postage Stamp

Postage Stamp

“75 years since the birth of I.A. Brodsky”

- On May 22, 2015, a postage stamp “75 years since the birth of I.A. Brodsky” went into circulation in Russia. In addition, an envelope was printed with a picture of the poet's house-museum in the village of Norinskaya.

- On May 24, 2015, the film “Brodsky is not a poet” by Anton Zhelnov and Nikolai Kartozia was released, telling about the work of Joseph Brodsky

- March 30, 2016 at London's largest bookstore Waterstones Piccadilly The opening of a bronze bust of Joseph Brodsky by the young Russian sculptor Kirill Bobylev took place. The bust will be displayed in the bookshop until it is moved to a permanent location at Keele University in Staffordshire, UK.

- On the occasion of the poet’s 76th birthday, Brodsky Days were held in May 2016 at the Yeltsin Center in Yekaterinburg.

Documentaries

- 1989- Brodsky Joseph. Interview in New York (dir. Evgeniy Porotov)

- 1991- Joseph Brodsky: continuation of water (dir. N. Fedorovsky, Harald Lüders)

- 1992- Joseph Brodsky. Bobo (dir. Andrey Nikishin) - concert film

- 1992- Performance (dir. Dmitry Dibrov, Andrey Stolyarov) - video poem-collage

- 1992- Joseph Brodsky. Poet about poets (Swedish and Moscow television) - film-discussion

- 1999- Marble (dir. Grigory Dityatkovsky) - tragicomic parable

- 2000- Walking with Brodsky (dir. Elena Yakovich, Alexey Shishov)

- 2000 - Brodsky - And my path will lie through this city... (dir. Alexey Shishov, Elena Yakovich)

- 2002- Joseph Brodsky (dir. Anatoly Vasiliev)

- 2002- Biblical story: Presentation. Joseph Brodsky (TV channel "Neophyte")

- 2005- Walking with Brodsky: Ten years later (dir. Elena Yakovich, Alexey Shishov)

- 2005 - Duet for voice and saxophone (dir. Mikhail Kozakov, Pyotr Krotenko) - musical and poetic performance

- 2006- Geniuses and villains of the passing era: Joseph Brodsky. Escape story (dir. Yulia Mavrina)

- 2006- One and a half cats, or Joseph Brodsky (dir. Andrei Khrzhanovsky)

- 2006- Angelo-mail (dir. Olesya Fokina)

- 2007- The end of a wonderful era. Brodsky and Dovlatov (dir. Evgeny Porotov, Egor Porotov)

- 2007- Stars of the sounding word. Alla Demidova - Poets of the 20th century: from Blok to Brodsky - literary readings

- 2007- Captured by angels. Letter in a Bottle (dir. Evgeniy Potievsky)

- 2009- One and a half rooms or a sentimental journey to the Motherland (dir. Andrei Khrzhanovsky)

- 2010 - Point of no return. Joseph Brodsky (dir. Natalya Nedelko)

- 2010- Joseph Brodsky. Return (dir. Alexey Shishov, Elena Yakovich)

- 2010- An island called Brodsky (dir. Sergei Braverman)

- 2010- Joseph Brodsky. Conversation with a Celestial (dir. Roman Liberov)

- 2010- Joseph Brodsky. On the influence of classical music on Brodsky’s poetry (TV channel “Culture”)

- 2010- Because the art of poetry requires words... (dir. Alexey Shemyatovsky) - literary and theatrical evening dedicated to the poetry of Joseph Brodsky on the Small Stage of the Moscow Art Theater. Chekhov

- 2011- Eight evenings with Veniamin Smekhov. I came to you with poems... (dir. Anastasia Sinelnikova) - creative evening

- 2012- Life of remarkable people: Joseph Brodsky (dir. Stanislav Marunchak)

- 2014- Observer. Joseph Brodsky (TV channel "Culture") - intellectual talk show

- 2015- Cult of Personality. Joseph Brodsky (Radio Liberty TV channel) - talk show

- 2015- Joseph Brodsky. From Nowhere with Love (dir. Sergei Braverman)

- 2015- Brodsky is not a poet (dir. Nikolai Kartozia, Anton Zhelnov)

Joseph Brodsky was born May 24, 1940 in Leningrad. Father, captain of the USSR Navy Alexander Ivanovich Brodsky (1903-1984), was a military photojournalist, after the war he went to work in the photo laboratory of the Naval Museum. In 1950 he was demobilized, after which he worked as a photographer and journalist in several Leningrad newspapers. Mother, Maria Moiseevna Volpert (1905-1983), worked as an accountant. Mother's sister is an actress of the BDT and the Theater named after. V.F. Komissarzhevskoy Dora Moiseevna Volpert.

Joseph's early childhood was spent during the years of war, blockade, post-war poverty and passed without a father. In 1942 after the blockade winter, Maria Moiseevna and Joseph went for evacuation to Cherepovets, returned to Leningrad in 1944. In 1947 Joseph went to school No. 203 on Kirochnaya Street, 8. In 1950 moved to school No. 196 on Mokhovaya Street, in 1953 I went to the 7th grade at school No. 181 in Solyany Lane and stayed for the second year the following year. In 1954 applied to the Second Baltic School (naval school), but was not accepted. He moved to school No. 276 on Obvodny Canal, house No. 154, where he continued his studies in the 7th grade.

In 1955 the family receives "one and a half rooms" in the Muruzi House.

In 1955, at less than sixteen years old, having completed seven grades and starting the eighth, Brodsky dropped out of school and became an apprentice milling machine operator at the Arsenal plant. This decision was related both to problems at school and to Brodsky’s desire to financially support his family. Tried unsuccessfully to enter submariner school. At the age of 16, he got the idea of becoming a doctor, worked for a month as an assistant dissector in a morgue at a regional hospital, dissected corpses, but eventually abandoned his medical career. In addition, for five years after leaving school, Brodsky worked as a stoker in a boiler room and as a sailor in a lighthouse.

Since 1957 was a worker in geological expeditions of NIIGA: in 1957 and 1958- on the White Sea, in 1959 and 1961- in Eastern Siberia and Northern Yakutia, on the Anabar shield. Summer 1961 in the Yakut village of Nelkan, during a period of forced idleness (there were no deer for a further campaign), he had a nervous breakdown, and he was allowed to return to Leningrad.

At the same time, he read a lot, but chaotically - primarily poetry, philosophical and religious literature, and began to study English and Polish.

In 1959 meets Evgeniy Rein, Anatoly Naiman, Vladimir Uflyand, Bulat Okudzhava, Sergei Dovlatov.

February 14, 1960 The first major public performance took place at the “tournament of poets” in the Leningrad Gorky Palace of Culture with the participation of A.S. Kushner, G.Ya. Gorbovsky, V.A. Sosnory. The reading of the poem “Jewish Cemetery” caused a scandal.

During a trip to Samarkand in December 1960 years, Brodsky and his friend, former pilot Oleg Shakhmatov, were considering a plan to hijack a plane in order to fly abroad. But they did not dare to do this. Shakhmatov was later arrested for illegal possession of weapons and reported to the KGB about this plan, as well as about another friend of his, Alexander Umansky, and his “anti-Soviet” manuscript, which Shakhmatov and Brodsky tried to give to an American they met by chance. January 29, 1961 Brodsky was detained by the KGB, but was released two days later.

In August 1961 in Komarov, Evgeny Rein introduces Brodsky to Anna Akhmatova. In 1962 during a trip to Pskov he meets N.Ya. Mandelstam, and in 1963 Akhmatova - with Lydia Chukovskaya. After Akhmatova's death in 1966 With the light hand of D. Bobyshev, four young poets, including Brodsky, were often mentioned in memoirs as “Akhmatov’s orphans.”