He became heir to the throne only at the age of 20, after the sudden death of his older brother. Began hasty preparation of Alexander Alexandrovich for this role. But, having received an army upbringing in childhood, the heir had a great inclination towards military sciences and was engaged in them with much greater enthusiasm than any other. The exception was Russian history, which he was taught by the famous scientist S. M. Solovyov. Alexander III headed the Historical Society, he had an excellent historical library.

In the autumn of 1866, he married the Danish princess Dagmar, who was named Maria Feodorovna at her marriage. Alexander III loved his wife very much, adored children. The emperor was fond of fishing, hunting, was distinguished by his huge growth, dense physique, possessed remarkable physical strength, wore a beard and a simple Russian dress.

Beginning of a new reign

The death of his father shocked Alexander Alexandrovich. When he looked at the bloody "tsar-liberator", who was dying in terrible agony, he vowed to strangle the revolutionary movement in Russia. The program of the reign of Alexander III contained two main ideas - the most severe suppression of any opponents of power and the cleansing of the state from "alien" Western influences, the return to the Russian foundations - autocracy, Orthodoxy, nationality.

On March 2, 1881, while receiving members of the State Council and courtiers who took the oath, the new tsar declared that, entering the throne at a difficult moment, he hoped to follow his father's precepts in everything. On March 4, in dispatches to Russian ambassadors, the emperor emphasized that he wanted to maintain peace with all powers and focus all attention on internal affairs.

Alexander III knew that his father had approved Loris-Melikov's project. The heir only had to formally approve it at a special meeting of senior officials and resolve the issue of publishing this draft in the press. M. T. Loris-Melikov was calm, believing that the will of the late sovereign was law for his heir. Among the government officials who gathered on March 8 for a meeting, the supporters of the project were in the majority. However, the unexpected happened. Alexander III supported the minority of opponents of the project, through whom K. P. Pobedonostsev spoke.

Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev (1827-1907) Born in the family of a professor of literature at Moscow University. He graduated from the School of Law and in 1859 was invited to the chair of civil law at Moscow University. Soon Pobedonostsev began to teach law to the sons of Alexander II. He developed a warm and trusting relationship with Alexander Alexandrovich.

Emperor Alexander II highly valued the professional and business qualities of Pobedonostsev and sought to use them on a state scale as well. Pobedonostsev held a number of responsible government positions, was a member of commissions for the development reforms in education and justice. And in April 1880 he was appointed chief prosecutor of the Synod and was soon introduced to the Committee of Ministers.

At first, Pobedonostsev was known as a moderate liberal, but then moved to a conservative position. Pobedonostsev disliked those "innovations" that were "written off" from Western European models. He believed that the foundations of European political life were unacceptable in general, and in Russia in particular.

In the very first hours after the assassination of Alexander II, Pobedonostsev made tremendous efforts to impose on the new emperor his own approaches to resolving the problems that had arisen. He wrote to the tsar: “You get Russia, confused, shattered, confused, eager to be led with a firm hand, so that the ruling power sees clearly and knows firmly what it wants and what it will not allow in any way.”

Encouraged by the emperor's support, Pobedonostsev, in secret from the rest of the ministers, compiled the text of the manifesto, with which on April 29, 1881, Alexander III addressed the people "to calm the minds." It followed from it that the tsar considers the main task of his reign to be the preservation of autocratic power "for the good of the people, from any encroachments on it." The hopes of liberal officials to introduce even some semblance of a constitution collapsed. Minister of Internal Affairs M.T. Loris-Melikov resigned. Together with him, the Minister of Finance A. A. Abaza and the Minister of War D. A. Milyutin left their posts.

Nevertheless, the manifesto of Alexander III was imbued with a spirit of respect for the reforms of the past reign.

Moreover, a desire was expressed to follow the reformist path further. This desire was even more clearly emphasized in the circular of the new Minister of Internal Affairs, N. P. Ignatiev, dated May 6, 1881. It stated that the government would work in close contact with representatives of social forces.

In June 1881, the first so-called "session of knowledgeable people" was convened, who were invited to take part in the development of a law to reduce redemption payments. And although "knowledgeable people" were not elected by the zemstvos, but were appointed by the government, among them were prominent liberal figures. The second "sessions of knowledgeable people", convened in September 1881, the question of resettlement policy was proposed.

Attempts to solve the peasant question

After the demonstrative resignation of the leading ministers, the new posts were by no means opposed to any reforms. Minister of the Interior N. P. Ignatiev, the former envoy of Russia in Constantinople, was a supporter of Slavophile ideas. Together with the prominent Slavophile I. S. Aksakov, he developed a project for convening a deliberative Zemsky Sobor. N. X. Bunge became Minister of Finance. He was reputed to be a very moderate, but liberal-minded politician, striving to alleviate the lot of the masses. The new ministers energetically took up the implementation of the bills developed under Loris-Melikov.

On December 28, 1881, a law on compulsory redemption was adopted, which had passed a preliminary discussion at a "session of knowledgeable people" peasants put on. Thus, the temporarily obligated state of the peasants was terminated. The same law included a provision on the widespread reduction of redemption payments by 1 ruble. Later, 5 million rubles were allocated for their additional reduction in some provinces. A preliminary discussion of the question of the distribution of this money between the provinces was left to the zemstvos.

The next reform gradually abolished the poll tax. During its preparation, Bunge experienced conflicting feelings. On the one hand, as Minister of Finance, he understood that with the abolition of the poll tax, the treasury would lose 40 million rubles annually. However, on the other hand, as a citizen, he could not help but see the whole injustice of the poll tax, its grave consequences - mutual responsibility, leading to restriction of the freedom of movement of peasants and the right to choose their occupations.

Bunge significantly streamlined the collection of taxes, which until then was carried out by the police often using the most unceremonious methods. The positions of tax inspectors were introduced, which were responsible not only for collecting money, but also for collecting information about the solvency of the population in order to further regulate taxation.

In 1882, measures were taken to alleviate the shortage of land among the peasants. Firstly, the Peasant Bank was established, which provided soft loans for the purchase of land by peasants; secondly, the lease of state lands was facilitated.

On the agenda was the issue of settling the resettlement policy. But its decision was delayed, as significant differences emerged in the approaches of the government and the specially convened "session of knowledgeable people". The law on resettlement appeared only in 1889 and actually included measures proposed by “knowledgeable people”: only the Ministry of the Interior gave permission for resettlement; settlers were provided with significant benefits - they were exempted for 3 years from taxes and military service, and in the next 3 years they paid taxes in half; they were given small amounts of money.

At the same time, the government of Alexander III sought to preserve and strengthen the peasant community, believing that it prevents the ruin of the peasants and maintains stability in society. In 1893, a law was passed that limited the possibility of peasants leaving the community. Another law narrowed the rights of the community to redistribute the land and assigned allotments to the peasants. According to the new law, at least 2/3 of the peasant assembly had to vote for the redistribution, and the period between redistributions could not be less than 12 years. A law was passed prohibiting the sale of communal lands.

Start of labor legislation

On June 1, 1882, a law was passed prohibiting the labor of children under 12 years of age. The same document limited the working day of children from 12 to 15 years old to 8 hours. A special factory inspectorate was introduced to supervise the implementation of the law. In 1885, the prohibition of night work for women and minors followed.

In 1886, under the direct influence of workers' uprisings, a law was passed on the relationship between employers and workers. He limited the amount of fines. All penalties imposed on the workers now went to a special fund used to pay benefits to the workers themselves. By law, it was forbidden to pay for work goods through factory shops. Special paybooks were introduced, in which the conditions for hiring a worker were entered. At the same time, the law provided for the severe responsibility of workers for participating in strikes.

Russia became the first country in the world to exercise control over the working conditions of workers.

The end of the "Ignatiev regime"

The new ministers continued the undertakings of Loris-Melikov on the issue of the reform of local self-government, including the peasant one. To summarize the material received from the zemstvos, N. P. Ignatiev created a special commission chaired by Secretary of State M. S. Kakhanov, who was Loris-Melikov's deputy. The commission included senators and representatives of zemstvos.

However, their work was soon stopped, as important changes took place in the Ministry of the Interior. They testified to changes in domestic politics. In May 1882, N.P. Ignatiev was dismissed from his post. He paid the price for trying to convince Alexander III to convene the Zemsky Sobor.

Count D. A. Tolstoy, who was dismissed in 1880 from the post of Minister of Public Education on the initiative of Loris-Melikov, was appointed to replace Ignatiev. From that moment on, new features began to appear more definitely in domestic politics, giving the reign of Alexander III a reactionary coloring.

Measures to combat "sedition"

The outlines of the new course were visible in the "Regulations on Measures for the Preservation of State Order and Public Peace" published on August 14, 1881. This document gave the right to the Minister of the Interior and the governors-general to declare any region of the country in an "exceptional position." Local authorities could expel undesirable persons without a court decision, close commercial and industrial enterprises, refer court cases to a military court instead of a civil one, suspend the publication of newspapers and magazines, and close educational institutions.

In the future, the political system of the Russian Empire began to acquire all the new features of a police state. In the 80s. there were Departments for the maintenance of order and public security - "Okhranka". Their task was to spy on the opponents of the authorities. The amount allocated to the police to pay secret agents increased. All these measures destroyed the foundations of legality, proclaimed during the reforms of the 60-70s.

Education and press policy

Having become the Minister of the Interior, D. A. Tolstoy decided to complete what he did not have time in the previous reign - to “put things in order” in the Ministry of Public Education. In 1884, the new Minister of Public Education, I. I. Delyanov, introduced a university charter, according to which the universities were deprived of autonomy, and the ministry got the opportunity to control the content of education in them. Tuition fees have almost doubled. It was decided to take students into "hedgehogs" by banning any student organizations. Those who showed open discontent were given to the soldiers.

Being engaged in secondary school, Delyanov "became famous" by the order of June 5, 1887, which received from the liberals the name of the law on "cook's children." Its meaning was to make it difficult for children from the lower strata of society to enter the gymnasium in every possible way. It was proposed to accept in the gymnasium "only such children who are in the care of persons who provide sufficient guarantee of proper home supervision over them and in providing them with the amenities necessary for their studies." This was done in order to “free themselves from the admission of the children of coachmen, footmen, cooks, laundresses, small shopkeepers and similar people into them, whose children, with the exception of perhaps gifted with extraordinary abilities, should not at all be taken out of the environment to which they belong. ". For the same reason, tuition fees have increased. In gymnasiums, the number of lessons devoted to the study of religious subjects and ancient languages was increased.

Pobedonostsev also made his contribution to the school business. He spoke out against zemstvo schools, believing that the children of peasants did not need the knowledge they received there, which was cut off from real life. Pobedonostsev contributed to the spread of parochial schools, obliging each parish to have them. The only teacher in such a school was the parish priest. However, the poorly educated, financially unsecured local clergy were not particularly happy about this additional burden. Teaching in most parochial schools was at an extremely low level. In 1886, at the insistence of Pobedonostsev, the Higher Women's Courses were closed.

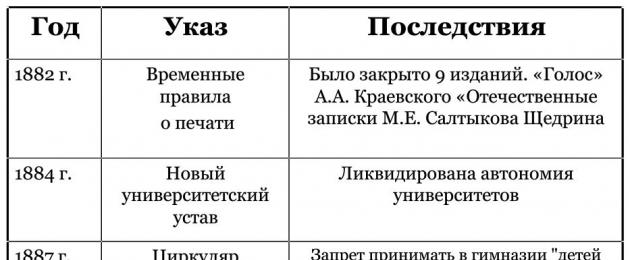

Prohibitive measures were also taken in relation to the press. In 1882, the Conference of the Four Ministers was formed, endowed with the right to prohibit the publication of any printed organ. Only in 1883-1885. by decision of the Meeting, where Pobedonostsev played the first violin, 9 publications were closed. Among them were the popular magazines "Voice" by A. A. Kraevsky and "Notes of the Fatherland" by M. E. Saltykov-Shchedrin.

The year 1884 brought another “novelty”: for the first time in Russia, a “cleansing” of libraries was carried out. 133 titles of individual books, collected works and journals previously allowed by censorship were considered "inadmissible for circulation" in public libraries and public reading rooms.

Strengthening the position of the nobility. Attack on local self-government

The appointment of D. A. Tolstoy as Minister of the Interior evoked approval from the conservative-minded nobles, who now hoped to restore their former position in society. In 1885, the opening of the Noble Bank took place. Its task was to provide soft loans to support the landowners' farms. In the manifesto on this occasion, the wish was expressed that henceforth "the Russian nobles retain their leading place in military leadership, in matters of local government and the court, in spreading by example the rules of faith and fidelity and the sound principles of public education."

On July 12, 1889, a law on zemstvo district chiefs was issued. He abolished positions and local institutions based on non-estate and elective principles: peace mediators, district presences for peasant affairs and the world court. In 40 provinces of Russia, 2,200 zemstvo sections were created. They were headed by zemstvo chiefs, who had broad powers, which were previously exercised by the institutions listed above. The zemstvo chief controlled the communal self-government of the peasants, instead of a magistrate, he considered minor court cases, approved the sentences of the volost peasant court, resolved land disputes, etc. Only nobles could occupy the positions of zemstvo chiefs.

This law solved several important tasks for the authorities at once. Subordinating peasant self-government to zemstvo chiefs, he strengthened the position of the local government and provided the nobles with the opportunity for prestigious service. The power of zemstvo chiefs became a kind of similarity to the pre-reform power of the landowners. The peasants, in fact, were placed in personal dependence on the zemstvo chiefs, who received the right to subject them to punishment without trial, including corporal punishment.

On June 12, 1890, the “Regulations on provincial and district zemstvo institutions” were published. In it, zemstvo self-government was considered as part of state administration, a grassroots cell of power. When zemstvos were elected, the estate principles were strengthened: the landowning curia became purely noble, the number of vowels from it increased, and the property qualification decreased. The electoral qualification for the city curia increased sharply, and the peasant curia practically lost independent representation, since peasants were now allowed to elect only candidates at volost meetings, who were then approved by the governor.

On June 11, 1892, a new city regulation was issued. It significantly increased the electoral qualification, formalized the practice of government interference in the affairs of city government. Mayors and members of councils were declared to be in the civil service.

National and religious policy of Alexander III

One of the main tasks of the national and religious policy of Alexander III was the desire to preserve the unity of the state. The way to this was seen primarily in the Russification of the national outskirts.

Not without the influence of Pobedonostsev, the Russian Orthodox Church was placed in an exceptional position. Those religions that he recognized as "dangerous" for Orthodoxy were persecuted. The chief prosecutor of the Synod showed particular severity towards sectarians. Often, children were even taken away from sectarian parents.

Buddhists (Kalmyks and Buryats) were also persecuted. They were forbidden to build temples, to conduct divine services. Particularly intolerant was the attitude towards those who were officially listed as converted to Orthodoxy, but in fact continued to profess the former religion.

The government of Alexander III showed a harsh attitude towards adherents of Judaism. According to the Provisional Rules of 1882, the Jews were deprived of the right to settle outside cities and towns, even within the Pale of Settlement; they were forbidden to acquire real estate in the countryside. In 1887, the Pale of Settlement itself was reduced. In 1891, a decree was issued on the eviction of Jews who illegally lived in Moscow and Moscow province. In 1887, it was determined what percentage of the total number of students in educational institutions could be Jews (percentage rate). There were restrictions on certain types of professional activities, such as advocacy. All these oppressions did not extend to Jews who converted to the Orthodox faith.

Catholic Poles were also subjected to persecution - they were denied access to government positions in the Kingdom of Poland and in the Western Territory.

At the same time, the Muslim religion and Muslim courts were left intact in the lands of Central Asia annexed to the Russian Empire. The local population was granted the right of internal self-government, which turned out to be in the hands of the local elite. But the Russian authorities managed to win over the working strata of the population, by lowering taxes and limiting the arbitrariness of the nobility.

Alexander III refused to continue the liberal reforms begun by his father. He took a firm course in preserving the foundations of autocracy. Reformatory activity was continued only in the field of economics.

The reign of Alexander III and the counter-reforms of 1880 - 1890s

As you already know, from this topic, that after the murder of his father, his son Alexander III came to the throne. The death of Alexander II shocked his son so much that at the beginning of his reign he began to fear various revolutionary trends, and therefore it was difficult for him to decide on a political course. But in the end, Alexander III succumbed to the influence of such reactionary ideologists as K.P. Pobedonostsev and P.A. Tolstoy decided to preserve autocracy and dislike for liberal reforms in the empire.

And since, after the brutal assassination of Alexander II, the public lost faith in the Narodnaya Volya with their terror and police repressions, the society changed its views towards conservative forces and counter-reforms.

Literally a month after the assassination of the emperor, Alexander III publishes the Manifesto "On the inviolability of autocracy." In the published Manifesto, Alexander III declares that he decided to preserve the foundations of autocracy in the state. With this Manifesto, he practically revived the order of Nicholas I, thereby strengthening the regime of the police state.

First of all, the Emperor dismisses M. Loris-Melikov, who was the main reformer during the reign of his father, and also replaces all liberal rulers with more cruel supporters of the chosen course.

K.N. became the main ideologist in the development of counter-reforms. Pobedonostsev, who believed that the liberal reforms of Alexander II did not lead to anything good, but, on the contrary, only caused upheavals in society. In this regard, he called for a return to the more traditional canons of national existence.

To further strengthen the autocracy, changes were made to the system of zemstvo self-government. After that, the zemstvo chiefs received unlimited power over the peasants.

By issuing the "Regulations on Measures to Preserve State Security and Public Peace", Alexander III expanded the powers of the governors and thereby allowed them to declare a state of emergency, expel without trial or investigation, bring them to a military court, close educational institutions and fight in the liberal or revolutionary movement. . Severe censorship was also introduced and all major liberal publications were closed.

All city self-government bodies and state institutions were under strict control.

The emperor also made his changes to the peasant communities, thereby forbidding the sale and pledge of peasant lands, which nullified the successes of his father's rule.

To educate the intelligentsia obedient to the authorities, the university counter-reform was also adopted. Strict discipline was introduced in all universities. For admission to the university, it was necessary to provide recommendations on the political reliability of students. In addition, people pleasing to the government were appointed to all significant university positions.

A Decree was also issued under the title "On Cook's Children". According to this Decree, it was forbidden to accept children, lackeys, laundresses, coachmen and other people who belonged to the lower class in the gymnasium.

Changes were made to factory legislation that prohibited workers from asserting their rights.

In addition, the policy towards the peasants was also tightened. They were canceled any benefits related to the redemption of land, and peasant allotments were limited in size.

During the reign of Alexander III, they tried in every possible way to stop admiration for the West, the ideas of a special Russian path and the identity of Russia were planted. In addition, the term tsar was returned and the cult of the monarch and the monarchy was spread everywhere.

The fashion of those times dictated the wearing of caftans, bast shoes and a beard.

And if we sum up the results of the counter-reforms carried out by the policy of Alexander III, then it can be considered rather contradictory. On the one hand, under his rule, the country experienced an industrial boom and a peaceful existence without wars from outside. But on the other hand, discontent among the population grew, tension appeared in society and social unrest intensified.

Questions and tasks

1. What circumstances had a decisive impact on the domestic policy of Alexander III?

2. Highlight the main directions of the domestic policy of Alexander III.

3. Compare the domestic policy of Alexander II and Alexander III. Where do you see the fundamental differences? Can you find commonalities?

4. What innovations of the previous reign were subjected to revision by Alexander III and why?

5. Give an assessment of the social policy of Alexander III. What do you see as its advantages and disadvantages?

6. Give an assessment of the national policy of Alexander III.

7. Do you agree with the statement that the period of the reign of Alexander III was a period of counter-reforms, that is, a period of liquidation of the reforms of the previous reign?

The documents

From the note of Count N.P. Ignatiev to M.T. Loris-Melikov. March 1881

No matter how criminal the actions of fanatics may be, the fight against any even fanatical opinion is possible and successful only when it is not limited to one impact of material force, but when the right thought is opposed to error, to this destructive idea - the idea of a correct state order. The most stubborn, most persistent, most energetic pursuit of sedition by all the police and administrative means at the disposal of the government is undoubtedly the urgent need of the moment. But such persecution, being a cure for the inner side of the disease, is hardly a fully effective means of struggle. The achievement of the ultimate goal and the eradication of evil is conceivable only under the indispensable condition - simultaneously with such a persecution - of the steady and correct direction of the state on the path of peaceful development by continuing the reforms and undertakings of the last reign ... Now ... is the most convenient moment to call for assistance to the government of the zemstvo people and offer to them for a preliminary discussion all those draft reforms that all of Russia is looking forward to with such impatience.

What is the Constitution? Western Europe gives us the answer to this. The constitutions that exist there are the instrument of any untruth, the instrument of all intrigues... And this falsehood, according to the Western model, unsuitable for us, they want, to our misfortune, to our destruction, to introduce in our country. Russia was strong thanks to the autocracy, thanks to unlimited trust and close ties between the people and their tsar ... But instead of that they propose to set up a talking shop for us ... We already suffer from talking ...

In such a terrible time ... one must think not about the establishment of a new one, in which new corrupting speeches would be made, but about deeds. We need to act.

Document questions:

1. What was the essence of the programs of Ignatiev and Pobedonostsev?

2. Which of them was adopted by Alexander III? Why?

Expanding vocabulary

Inspector- an official who checks the correctness of someone's actions.

Sedition- conspiracy, rebellion, something forbidden.

Resettlement policy- the movement of the population for permanent residence in the sparsely populated outlying regions of Russia - in Siberia, the southern Urals, the North Caucasus, Novorossia, the Lower Volga region, and free lands.

police state- a characteristic of the political system, in which the suppression of internal opponents is practiced by the methods of political violence, surveillance and investigation by law enforcement forces. In such a state, there is control over the location, movement, behavior of citizens, information is being collected about obvious and probable opponents of the authorities.

Reaction- the policy of active resistance to progressive changes in society.

sectarians- members of religious groups that do not recognize the teachings of the main church.

Circular- order of the authority to subordinate institutions.

Pale of Settlement- the territory on which it was allowed in 1791-1917. permanent residence of Jews in Russia. Covered 15 provinces.

Danilov A. A. History of Russia, XIX century. Grade 8: textbook. for general education institutions / A. A. Danilov, L. G. Kosulina. - 10th ed. - M.: Enlightenment, 2009. - 287 p., L. ill., maps.

- In contact with 0

- Google Plus 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0