"Best in nobility" or "First of the venerable"- female pharaoh of the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt from the XVIII dynasty - Maatkara Hatshepsut Henmetamon - Queen Hatshepsut

Queen Hatshepsut was the daughter of the third pharaoh of the XVIII dynasty, Thutmose I and Queen Ahmose, the granddaughter of the founder of the New Kingdom, Pharaoh Ahmose I. During the life of her father, Hatshepsut became the “Wife of God” - the high priestess of the Theban God Amun. Hatshepsut was the only female pharaoh in Egyptian history who managed to place the double crown of Lower and Upper Egypt on her head.

Hatshepsut was given all the secular and religious honors due to the pharaohs, she was depicted, as befits a real pharaoh, with the attributes of Osiris, with a beard tied under her chin. After the death of her father, Thutmose I, she married her half-brother Thutmose II. When he died at a fairly early age, his only heir was the young Thutmose III, the son of one of the pharaoh's younger wives. Hatshepsut ruled the state on his behalf for 22 years.

Egyptian pharaohs were considered the earthly incarnation of the god Horus and could only be men. When the female pharaoh Hatshepsut ascended the throne, a legend was invented to legitimize her power, according to which the god Amon himself descended to earth to conceive his daughter in the guise of Thutmose I.

In the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut - Djeser-Djeseru or “Holy of Holies” in Deir el-Bahri, built by her favorite and court architect Senmut, hieroglyphic inscriptions have been preserved, which are descriptions of the events associated with the birth of Hatshepsut, as well as ritual formulas . The translation of each inscription is preceded by a brief description of the relief image to which it refers. On one of the reliefs, Amon informs the gods (Montu, Atum, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris, Isis, Nephthys, Seth, Hathor) about the upcoming conception of a new “king” who will be given power in the country.

Amun's words to the gods:

“Behold, I loved the wife chosen by me, the mother of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkar, endowed with life, Khnumit-Amon Hatshepsut... I will be the protection of her flesh... Behold, I gave her all the countries of Egypt and all foreign countries... She will lead all living... I united for her both Earths in contentment... She will build your temples, she will sanctify your houses... she will make your altars prosperous...”

The reign of Hatshepsut marked unprecedented prosperity and rise in Egypt. Of all the areas of her state activity, Hatshepsut showed herself primarily as a pharaoh-builder. The queen restored many monuments destroyed by the Hyksos conquerors. Two obelisks of Hatshepsut, about 30 meters high, next to the pylon of the temple of Amun-Ra in Karnak were the tallest of all those built early in Egypt until they were laid with stone masonry by Thutmose III (one of them has survived to this day).

Hatshepsut was actively involved in the construction of temples: in Karnak, the “Red Sanctuary” of Hatshepsut was erected for the ceremonial boat of the god Amun. Her name is associated with a sea expedition to the distant country of Punt, also known as Ta-Necher - “Land of God”. The location of the country of Punt has not been precisely established; perhaps the northern coast of Somalia; according to other sources, India.

As Irina Darneva writes in her book “The Silence of the Sphinx,” these obelisks resemble Gates to Heaven, through which an invisible ray of distant worlds passes and pink granite gives them an unearthly state. The queen chose pink color not by chance, because pink pearls are considered a symbol of Venus and correspond to the dawn. “Light of the Dawn” - this is how Venus was addressed in ancient times.

Hatshepsut was considered the daughter of the Solar dynasty of pharaohs, as well as an ordained priestess with a high spiritual position, her destiny was known to the Priests of the Karnak Temple.

The greatest structures of the New Kingdom era were the temples, or “houses” of the gods, as the ancient Egyptians called them. The waters of the Nile divided Ancient Egypt into the Kingdom of the Living and the Kingdom of the Dead. On the eastern bank of the Nile, palaces of the pharaohs and huge temples glorifying the gods were erected; on the western bank, pyramids, tombs and mortuary temples were built in honor of the dead and deified pharaohs.

In Luxor, at the very foot of the Deir el-Bahri cliffs, there is the most unusual monument of ancient Egyptian architecture - the funeral temple of Queen Hatshepsut, dedicated to the goddess Hathor. The temple stands at the foot of the steep cliffs of the Libyan plateau; it was erected in the middle of the second millennium BC next to the funeral temple of Pharaoh Mentuhotep I, the founder of the dynasty to which Hatshepsut belonged.

Construction of the mortuary temple began during the lifetime of Queen Hatshepsut. Djeser-Djeseru or “Holy of Holies” is what Hatshepsut called her mortuary temple. On the border of the desert and irrigated land, a giant pylon was erected, from which a processional road, about 37 meters wide, led to the temple itself, which was guarded on both sides by sphinxes made of sandstone and painted in bright colors. Right in front of the temple there was a garden of strange trees and shrubs brought from the mysterious country of Punt. Two sacred lakes were dug here.

The temple itself was truly a marvel of ancient Egyptian engineering. Carved into limestone rocks, it consisted of three huge terraces, located one above the other. On each of the terraces there was an open courtyard, covered rooms with columns and sanctuaries extending into the thickness of the rock. This grandiose plan was embodied by the hands of the architect Senenmut, the queen’s favorite and teacher of her daughter Nefrur.

Almost three and a half thousand years have passed. The book of Daniel says, “And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth will awaken, some to everlasting life, others to everlasting contempt and disgrace.” Archaeologists managed to find a statue of Hatshepsut with an intact face. In 2008, it was officially announced that the mummy of Hatshepsut rested in the Cairo Museum.

HATSHEPSUT IS THE ONLY FEMALE PHARAOH OF EGYPT. OPENING OF THE CENTURY!

The pyramids of Ancient Egypt are rightfully considered one of the wonders of the world. They are as mysterious as they are majestic and unique. And whenever Egyptologists manage to shed light on at least one of the secrets of the ancient pyramids, it becomes a sensation. The discovery of the mummy of Queen Hatshepsut is one of the latter and has already been called one of the most important discoveries of our century.

The mummy of Hatshepsut was considered lost for a long time. But its discovery, according to the head of the Supreme Council for the Study of Antiquities of Egypt, doctor and, in fact, the author of the discovery, Zaha Hawass, today is comparable in importance only to the discovery of the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun by Carter in 1922. And although they are trying to challenge Hawass’s hypothesis, for connoisseurs of Egyptian culture, the latest work of the “antiquities hunter” has become a real gift. The Egyptologist, who gained fame as Indiana Jones, posted a detailed report on his discovery on the website guardians.net.

Dr. Hawass made an effort to identify the mummy of Queen Hatshepsut back in 2006, when he began identifying unidentified female mummies. Three of them were in the Cairo Museum. But the fourth is buried under the letter KV60 in the Valley of the Kings. Interestingly, this mysterious sarcophagus was discovered by Howard Carter in 1903. The tomb had already been robbed before, but Carter was still incredibly lucky. In total, he found two mummies. One of which belonged to a small woman. The second was to an extremely obese person who was lying next to the tomb. But Carter sealed the sarcophagus. Apparently due to the lack of treasures in it.

In 1906, the same tomb was explored by another prominent British Egyptologist, Edward Ayrton. He managed to read the name of the woman in the sarcophagus: her name was Sitre-In, and she was Hatshepsut's nurse. He sent the find to Cairo. But Airton could not identify the second mummy found on the floor. Many years later, in 1989, anthropologist Donald Ryan once again explored the tomb. But in the end, the mummy went to the museum nameless.

But why did Dr. Hawass decide that she was Hatshepsut? The key to solving this mystery was in the wooden box containing the regalia of her throne. It was there that, in addition to the canopic jars, the queen’s only molar tooth was found. The researcher suggested that following tradition, the embalmers placed Hatshepsut's tooth in a box as a ritually charged object.

Canopic jars are vessels with organs. It is known that organs removed during mummification were not thrown away or destroyed. They were also preserved. After extraction, they were washed and then immersed in special vessels with balm - canopic jars.

All unidentified female mummies and found objects, as well as the mummies of pharaohs Thutmose II and III, because the first is Hatshepsut's half-brother, and the second is her stepson, were subjected to a thorough examination. This was once not possible, but modern advances have allowed Egyptologists to make significant progress. CT scans and DNA analysis of the mummies left no doubt. The mummy of an obese 50-year-old woman with a missing molar is Hatshepsut.

In addition, it turned out that the female pharaoh suffered from many diseases, including diabetes and even cancer - metastases were found in almost all the queen’s bones, and most likely it was one of the diseases that caused her death. Thus, the version that Hatshepsut died as a result of a violent death is completely refuted. As well as the fact that all the temples and monuments erected by the queen were destroyed by her stepson Thutmose III out of revenge.

Head of the Supreme Council of Antiquities of Egypt, Dr. Zahi Hawass: “When I started researching and searching for the mummy of Hatshepsut, I didn’t really think that I would be able to identify the queen’s mummy. I saw the experiment as an excellent opportunity to study unidentified female mummies from this particular dynasty. Modern scientific technology has never been used in their research before. There are many unidentified mummies of high status, found mainly in royal caches. This is a series of secret graves. And we must realize that in order to preserve the mummies and protect them from robbers, many bodies were hidden and moved by dedicated people to nearby graves. For example, we know from historical accounts that the mummy of Ramses II was initially moved from her tomb to the tomb of his father Seti I. This was a very important point and argument in the search for Hatshepsut's mummy. And the first thing I did was pay attention to the small, undecorated tomb of KV60 in front of the real tomb of the queen. I then studied all the mummies found in this burial and came to the conclusion that they actually moved. And at that moment I decided to go down to the original tomb of Hatshepsut - KV20. I don't think many people entered this grave. Even Egyptologists who worked in the Valley of the Kings escaped this because KV20 is one of the most difficult tombs in the valley."

Ancient Egypt. The reign of the XVIII dynasty of the pharaohs. By order of Pharaoh Thutmose III, inscriptions from the walls are violently knocked down, all evidence and references to the reign of Pharaoh Hatshepsut are destroyed. But why? Because this is a woman who proclaimed herself a pharaoh, wearing men's clothing and a false beard. It was unthinkable, but it happened. And she ruled for 23 years. And quite successfully. Many innovations, events, and, of course, many magnificent architectural monuments are associated with her name. Majestic famous obelisks, the stunningly beautiful temple in Deir el-Bahri, a number of buildings in Karnak. Truly an incredible woman who was able to achieve success against all odds!

But in order for the story about Hatshepsut to become more complete and understandable, we should go back a little in time in order to better understand the difficult period during which the queen ruled and what influenced her.

Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri

The period between the Middle and New Kingdoms turned out to be extremely difficult. Egypt was captured by the Hyksos. This led not only to political but also economic decline. The country again began to fall apart into separate nomes. There was no strength left for art; during this period everything comes to depersonalization and loss of individuality. Everything that was achieved by Senusret III and Amenemhet III is lost in the past. Old faceless canons appear on the stage. The whole reason was the lack of funds. There was nothing left to build architectural monuments and maintain art workshops. Therefore, both knowledge and skills were gradually lost. The Hyksos kings accepted the traditions of the Egyptians and preserved their culture, but still their works were very different from the Egyptian ones. The occupation lasted about 200 years. Liberation from the Hyksos began in Thebes. And nothing could stop the Egyptians in the fight for their lands and freedom. And after failures, the death of the pharaohs on the battlefields, the Egyptians completely liberated the Nile Valley and even, pursuing enemies outside their homeland, invaded Syria.

After liberation, it was in Thebes that art began to revive, under the reign of the 17th dynasty of pharaohs. And during this period some changes were made. In the art of weapons, something from the Hyksos was added, and with the development of trade, new trends came from Syria and Crete. In other areas, which did not have such close contact with the Hyksos or trade with other countries, the old traditions continue in full force. But everything related to monumental architecture continued the traditions of the Old Kingdom; it was an indicator of the continuity of the new dynasty to the previous one.

And one of the most interesting periods in the history of Egypt begins with the completion of victories over the Hyksos under the leadership of Ahmes I. The country achieves simply incredible power. After the capture of the capital of the Hyksos, Avaris, campaigns against Asia begin. Ahmes I fought in Syria, his son Amenhotep I reached the Euphrates, and Thutmose I already considers the Euphrates to be his northern border. And looking ahead a little, the campaigns of Thutmose III cemented Egypt’s role as a world power for a long time. And on this wave, chronicles and autobiographies of great figures appear. One of the most famous chroniclers of the annals was Januni, who accompanied Thutmose III on all his military campaigns. He made very vivid descriptions of all victories.

Changes in Egypt also affected religious views. The new political situation in Egypt also required one national main god, who became the Theban god Amun. After all, it was Thebes that advocated the unification of the country and was the capital of the victors. To give Amon an aura of antiquity, he was merged with the solar god Ra. God was given the appearance of a pharaoh. This is how the “king of all gods” appeared - Amon Ra. It was during this period that the most active construction began in Ancient Egypt - the construction of the Karnak Temple, which I already wrote about separately. The most prominent and talented architect was Ineni; the rise of architecture and the emergence of a whole school of talented architects began with him. Ineni himself built under five pharaohs. Under Thutmose I, Ineni was appointed chief architect at Karnak.

Sanctuary of Hatshepsut at Karnak

After the reign of Thutmose I, the female pharaoh Hatshepsut, the daughter of Thutmose I, was on the royal throne. During his lifetime, Hatshepsut was given in marriage to her half-brother Thutmose II.

Birth of Hatshepsut.

Queen Ahmose, mother of Hatshepsut, is led to the birthplace

But he was very weak and sickly, so he died early, leaving Hatshepsut with two daughters. She, of course, was of royal blood and, if she had been a man, would have taken the throne. But she is a woman and this was unacceptable. And Thutmose II also had a son from a concubine of a non-royal family, and was the only boy of all possible heirs. As a child, he was betrothed to his half-sister and declared pharaoh, but Hatshepsut was appointed regent.

Hatshepsut and Thutmose III

This practice was common among royal families over the centuries and in many countries. And time was counted from the beginning of the reign of Thutmose III, and in all images he is shown as a pharaoh, and behind him Hatshepsut was depicted with the attributes of a simple queen. But having achieved the favor and veneration of the priests, the love of the people, thanks to his wise rule, Hatshepsut independently ascends to the throne.

Hatshepsut. Drawing.

But not all the priests supported her in this and believed that she had seized the throne. But the number of adherents was high, both among those who had served her father and among younger ones. And this helped the queen become the true pharaoh of Egypt. Hatshepsut began to be portrayed as a full-fledged and sole pharaoh, albeit in male form. This story is about a woman who is capable of changing legislation and the rule of several dozen dynasties. About a woman who boldly declared her right to the throne and was capable of not only becoming one of the first female pharaohs, but also managing to achieve considerable success, especially in the field of construction. After all, it was under Hatshepsut that the most beautiful obelisks of incredible size were erected, and massive changes were made to the Karnak Temple.

Obelisk of Hatshepsut at Karnak

And, of course, one of the most magnificent temples of Ancient Egypt is the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut in the Valley of the Kings.

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

This woman deserves admiration even after 35 centuries. She did something incredible, even by today's standards. Defend the right to the throne in a world where it was unheard of, and hold out until your very last days.

Let's start with the obelisks. Their height exceeded the height of the obelisks built by her father and was equal to 30.7 m. All manufacturing and installation work took about 7 months. The inscription on the obelisk reads: “She made them as a monument to her father Amun, lord of Thebes, head of Karnak, erecting for him two great obelisks of eternal southern granite with tops from the best electra of all countries, which are visible on both banks of the Nile. Their rays flood Egypt when the sun rises between them, when it rises on the heavenly horizon.” The obelisks were installed in the northern part of one of the halls of the Karnak Temple, which had to be dismantled. But I think Hatshepsut did it with pleasure, because once upon a time it was in this hall that some of the courtiers chose Thutmose III as the only successor to the throne. While Hatshepsut herself was a legitimate queen on both her father’s and mother’s sides.

Obelisks of Hatshepsut. Photos taken from the Isis Project website

Fallen Obelisk

The names of several architects are associated with the monuments built under Hatshepsut - Hapuseneb, Senmut, Puimra, Amenhotep and Thuti. Puimra and Amenhotep supervised the production and installation of obelisks in the temple of Amun Ra. Hapuseneb was apparently already advanced in years when Hatshepsut came to power. He was from a noble priestly family and was therefore chosen for the position of high priest and chief architect. He led the construction of all the most important monuments during the early reign of the queen. Subsequently, all outstanding monuments are associated with the name of Senmut, the closest person to Hatshepsut. Despite his humble origins, he achieved incredible heights and became one of the most influential people in Egypt. Senmut was involved in the education of the queen, the heir of Nefrur, was the keeper of the seal, the head of the palace, the treasury, the house of Amun, the granaries of Amun, “all the works of Amon” and “all the works of the king.”

Senmut with daughter Hatshepsut

Senmut with daughter Hatshepsut

There is an assumption that Senmut and Hatshepsut were lovers. Senmut himself characterizes his position in the following words: “I was the greatest of the greats in the whole country. I was the keeper of the king's secrets in all his palaces, a private adviser at the right hand of the ruler; constant in favor and one having audiences, loving truth, impartial, one whom judges listened to and whose silence was eloquent. I was the one on whose words his master relied, whose advice the Lady of the Two Lands was satisfied, and the heart of the god’s wife was full. I was a nobleman who was listened to, for I conveyed the king’s word to his retinue. I was the one whose steps were known in the palace, the true adviser to the ruler, entering in love and leaving in mercy, gladdening the heart of the ruler daily. I was useful to the king, faithful to God and blameless before the people. I was the one who was entrusted with the flood, so that I could direct the Nile; to whom the affairs of the Two Lands were entrusted. Everything that the South and North brought was under my seal, the work of all countries was under my jurisdiction. I had access to all the writings of the prophets and there was nothing from the beginning of time that I did not know.”

Image of Senmut

Senmut enjoyed enormous power, so he had very good opportunities to realize all his creative ideas. In Egypt, there was such a practice - the architect erected his statue near the objects he built. From here we can judge what was built by Senmut.

Unfortunately, many of the buildings of Senmut have not reached us and we cannot judge them fully. But on the other hand, one of the greatest creations of Ancient Egypt has reached us - the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahri, which screams about the genius of the architect who created it. And on the other hand, it makes us regret that other works of this talented architect have not reached us.

Reconstruction of the temple

Reconstruction of the temple complex. Temple of Hatshepsut, Mentuhotep II and Thutmose III

Hatshepsut built a lot in Karnak, but later Thutmose III destroyed all her inscriptions or replaced them with the names of his father Thutmose II, who was generally completely faceless.

Image in the Karnak Temple. Amon - Ra crowns Hatshepsut

Also at Karnak, Thutmose III built a temple to Amun so as to completely cover the buildings of Hatshepsut. He erased all her names from the pylons and everything began to look like his father had built it. But, despite all his efforts, the world still knows about the great woman - Pharaoh Hatshepsut.

Reliefs of Hatshepsut destroyed by Thutmose III

Images of Thutmose II, father of Thutmose III

The name of Thutmose II in the Temple of Hatshepsut.

Mortuary temples played an important place in the architecture of the New Kingdom. A major change was the separation of the temple from the tomb itself. The temples were built on the border between the desert and fertile land, and the tombs themselves were built in rock gorges. Of the surviving such temples, the temple of Amenhotep I and Queen Nefertiri is known. To the south of it stood a temple - a prayer house, from which there was a road to Deir el-Bahri, to the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut. To the south stood the temples of Thutmose III, Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III. Thus, the mortuary temples of the Eighteenth Dynasty were located from north to south in the order in which the pharaohs ruled and lived.

On the right in the photo is the Temple of Hatshepsut

On the left is a complex of mortuary temples

Road from the Temple of Hatshepsut

It is not for nothing that Ineni is considered a great architect, because it was he who came up with the idea of a new layout for the royal burials. He talks about the construction of the royal tomb in his autobiographical inscription: “I alone watched as the rock tomb of His Majesty was carved out and no one saw and no one heard... I stayed awake in search of what was excellent. This was the kind of work that our ancestors did not do.” Most likely, this refers to the construction of the temple of Amenhotep I. But although the temples received a new appearance, the layout remained the same, because it was necessary for rituals and the premises had to correspond to them. At first, the rock tombs were small and decorated modestly. But gradually the size increased, the corridors lengthened, the halls became larger, and the number of utility rooms also increased. Architectural design also developed. The number of columns and their location began to depend on the size. And now in the tomb of Hatshepsut there are already 3 columns in the burial hall and one in the room in front of the burial hall.

Mortuary temples gradually became monumental structures with long avenues of sphinxes, massive pylons and statues of pharaohs standing in front of them. But due to the fact that much has not been preserved or has come to us in an already poor condition, we cannot analyze everything in detail. The temple of Amenhotep III, which has not survived, is especially upsetting. Judging by its remains, it was a magnificent structure. What remains from it are the sphinxes located in the alleys, and the colossal royal statues that once stood in front of the pylon, and now tower alone in the middle of the plain.

Statues of Amenhotep III, known as the Colossi of Memnon

But, of course, of all that has survived, the temple of Hatshepsut stands out. This temple had a special design. It was built next to the famous sanctuary of Mentuhotep II, and it was built according to his model. Mentuhotep was especially revered by the Egyptians, because it was with him that the Theban dynasty of pharaohs began, his temple was a family sanctuary.

Temple of Hatshepsut. Nearby is the ruined temple of Mentuhotep II.

And next to such a place Hatshepsut erects his temple, thereby emphasizing his belonging to the dynasty and the right to occupy the throne of Egypt, once conquered by Mentuhotep. This was to strengthen their position on the throne, where women were not allowed to enter. And this was so unusual for Ancient Egypt that the famous researcher Jean-Francois Champollion, the first person to decipher Egyptian writing, was confused. In the temple of Hatshepsut, he saw two names side by side - Thutmose III and Hatshepsut. The two of them were depicted as men - in men's clothing, with a beard and with the attributes of the power of a pharaoh. But the main catch was that everything about Pharaoh Hatshepsut was written in the feminine gender. Champollion was confused and could not understand what was going on. They portray a man, but write as a woman. And only later, thanks to research, archaeologists found out that it was a female pharaoh. She dared to claim the throne. After all, of all the children, only she outlived her father. Therefore, the temple that she erected spoke to everyone around about her greatness and power. That she is a worthy successor to her father Thutmose I.

The temple also became the largest among all the temples built before it. Hatshepsut built it high in the mountains and was connected by a long road to the prayer house located in the valley. Along this road there were sphinxes with the head of Hatshepsut.

Sphinx Hatshepsut

The southern wall of the large courtyard in front of the temple was decorated with pilasters with alternating images of a falcon in a double crown and a uraeus. Below were carved the names of Hatshepsut and schematic images of the facade of the palace. The western side of the courtyard was occupied by a portico with two rows of columns - twenty-two in each. The columns of the first row at the front were decorated in the same way as the pilasters of the south wall. On the inside, the columns had eight sides, like the proto-Doric columns of the second row. Above the architrave there was a cornice with a balustrade and drains for water.

The southern wall of the large courtyard in front of the temple was decorated with pilasters with alternating images of a falcon in a double crown and a uraeus. Below were carved the names of Hatshepsut and schematic images of the facade of the palace. The western side of the courtyard was occupied by a portico with two rows of columns - twenty-two in each. The columns of the first row at the front were decorated in the same way as the pilasters of the south wall. On the inside, the columns had eight sides, like the proto-Doric columns of the second row. Above the architrave there was a cornice with a balustrade and drains for water.

Protodoric columns

From the south and north, the portico was decorated with statues of Hatshepsut in the image of the god Osiris and reached 8 meters in height.

There were various painted reliefs on the walls of the portico. The Egyptians depicted how they brought obelisks and presented them to the god Amun, how they brought captives from Nubia, a parade of warriors and various cult scenes. On the walls on the other side was Hatshepsut herself in the form of a sphinx, defeating enemies and making sacrifices to Amon. The portico is divided in the middle by a large monumental staircase that leads to the first terrace of the temple. Trees grew on both sides of the stairs, and nearby there were ponds with thickets of papyrus. From the very gate to the stairs there were two sphinxes every 10 meters. The figures of lions on the side walls seemed to guard the entrance. The second courtyard, on the lower terrace on the north side, was not completed. The unfinished colonnade remained there. On the western side, the courtyard was closed by a portico with two rows of tetrahedral columns, separated by a staircase leading to the second terrace. Here the walls are decorated with the most famous reliefs - the coronation of Hatshepsut, her birth by mother Ahmes from Amun himself. In the southern part, an expedition to Punt, from where incense and exotic animals were brought.

Porticoes of the temple

Wall reliefs of the Temple of Hatshepsut

Sacrificial animals

Hatshepsut's march to Punt

Khnum and Hekate lead the pregnant Queen Ahmose, Hatshepsut's mother, to the birthplace

On both sides of the portico of the lower terrace there were prayer houses for the god Anubis and the goddess Hathor. The right chapel, carved into the rock, consisted of a hall with 12 fluted columns, behind which was the sanctuary of Anubis. The sanctuary of Hathor was large. The first hall had 32 columns with capitals in the form of Hathor's head. Behind this hall there was a small hall with two columns, from which side doors led into niches, and the middle door into a sanctuary of two rooms.

Sanctuary of Anubis

Sanctuary of Hathor. View from above.

Sanctuary of Hathor

The staircase was decorated very interestingly. At the bottom of the railing were cobras whose tails snaked up the railing. On the back of each snake sat a falcon. This was a tandem of the gods of northern Egypt, the cobra Buto, and the god of northern Egypt, the falcon Behudti, which symbolized the unity of the entire country. In front of the stairs were sphinxes made of red Aswan granite.

Falcon Behudti

The layout of the upper terrace was more complex. This entire part of the temple was intended for performing main rites, and therefore it was accessible only to a narrow circle of people. This explains the peculiar design of the terrace portico, in front of which stood the Osiric statues of Hatshepsut. These 5.5 meter statues are visible even from afar. The main part of the terrace is surrounded on all sides by a colonnade, and entry into it was through a massive granite door. There are chapels adjacent to the terrace on the southern and northern sides. One of the southern chapels is dedicated to the cult of Hatshepsut's father, Thutmose I. In other chapels there were images of processions of priests, and there was an altar along which you had to climb steps.

Temple pylon

Temple pylon

10 large and 8 small niches were carved into the depths of the central terrace. In the large ones there were Osirian statues of the queen, 3.35 m high. Small niches were closed with doors, and on their walls they depicted Hatshepsut in front of the sacrificial table. In the middle of the wall was the main chapel, which contained a marble statue of Hatshepsut.

Entrance to the sanctuary. On the walls are niches with Osiric statues of Hatshepsut

Entrance to the sanctuary

Thus, the temple of Hatshepsut was a monument of grand scale and superbly decorated, striking in its severity and geometric lines and shapes. The façade solution was constructed by alternating the horizontals of the terraces with the verticals of the colonnades. The inclined planes of the stairs perfectly connect these horizontal and vertical lines into one whole, and if you consider that the road smoothly flows into the stairs, you get the impression of rising up. And the entire monumental monument looks light and slender.

Despite the similarity between the temples of Hatshepsut and Mentuhotep II, they have significant differences. They are characterized by geometricity and strict lines, but the temple of Hatshepsut is more diverse and has a lush decorative effect.

Plan of the Temple of Hatshepsut. On the left is a plan of the entire temple complex at Deir el-Bahri

Plan of the Temple of Hatshepsut

Section of the Temple of Hatshepsut

And the striking difference is the sculptures, of which there are over 200. In the temple itself there were at least 22 sphinxes, 40 Osiric statues and 28 statues depicting the queen sitting or kneeling. And about 120 more sphinxes decorated the courtyards and the road. During the 18th Dynasty, the role of sculpture greatly increased.

Hatshepsut statue

The head of the treasury and the head of the royal workshops, Hatshepsut, who supervised the work in the Deir el-Bahri temple, talks about the temple in the inscription on the mortuary wall of his tomb. He writes that "External the doors of the temple were made of black copper with electra inlays, and all the interior doors were made of real cedar with bronze details. Floor, according to Thuti, at least in one of the parts of the temple, was made of gold and silver, and its beauty was like the horizon of the sky.”

The temple was decorated in abundance with ornaments. Above the cornices of doors and niches there were most often in the form of alternating symbols of Osiris and Isis, or in the form of a kind of “secret” rebus images of the name Hatshepsut. In the prayer house of Hathor, lions were depicted on reliefs. Their motley striped manes, made in the form of conventional concentric circles on the shoulders, are very indicative of the ornaments of the Hatshepsut temple. Subsequently, all this pomp and decorativeness was actively developed by subsequent dynasties of pharaohs.

The temple at Deir el-Bahri was the most important during the reign of Hatshepsut. And Senmut’s attention was drawn specifically to him. And he even risked depicting himself on one of the walls of the temple. But these images were always positioned so that they would later be hidden behind doors. Obviously they were not intended for public viewing. And Senmut did an even more daring act - excavations discovered a secret tomb that Senmut had made for himself under the first courtyard of the temple. Moreover, the tomb of Senmut had been known for a long time, and therefore the discovery of the second tomb, and even in the temple of Hatshepsut, came as a surprise to researchers. The shape of this tomb is close to that of the royal tombs. Therefore, Senmut stands out from all the nobility and nobles. Particularly indicative is the inscription in the first hall of the tomb, made in large hieroglyphs along the very central part of the ceiling along its entire length: “ Long live Horus the following is the full title of Hatshepsut, king of Upper and Lower Egypt, beloved of Amon, living and keeper of the seal, chief of the house of Amon Senmut, conceived by Rames and born by Hatnefret.” The construction of such a semi-royal tomb and such an inscription was an unusually courageous act. And there is a version that this was the cause of Senmut’s death. Senmut's secret tomb was left unfinished, and there are no traces of burials, either in it or in the official tomb. This is the story of the creator of the temple at Deir el-Bahri, the magnificent architect and favorite of Hatshepsut, Senmut.

Drawing by artist Mikhail Potapov

Subsequently, Hatshepsut's daughter, heir to the throne, Nefrura, also dies.

The Temple of Hatshepsut did not retain its beautiful appearance for long. After the death of the queen, Thutmose III came to power, and not immediately, but after several years of reign, he ordered the destruction of all the statues of Hatshepsut, which interfered with his independent rule.

Hatshepsut. Drawing by Mikhail Potapov

Thutmose III. Drawing by Mikhail Potapov

Thutmose III. One of the greatest pharaoh warriors of Ancient Egypt.

Numerous temple sculptures were broken into pieces and buried nearby, where they were discovered by excavations.

Broken statue of Hatshepsut

Studies of Hatshepsut's mummy showed that she died of disease at the age of 40-50 years.

The reign of Hatshepsut marked unprecedented prosperity and rise in Egypt. She also proved herself to be a pharaoh-builder. The queen restored many monuments destroyed by the Hyksos conquerors. In addition, she herself actively led the construction of temples.

Thutmose III, the adopted son of Hatshepsut, ordered the destruction of all images, references, and altars of Hatshepsut to get rid of the power of his stepmother. By his order, all official chronicles were rewritten, the name of the queen was replaced with the names of this ruler and his predecessors; all the deeds and monuments of the queen were henceforth attributed to Hatshepsut’s successor.

(from Wikipedia)

She was depicted as a man. She was considered a usurper. She was erased from history. Her mummy was considered lost. And only today we begin to penetrate the secrets of Hatshepsut.

Regent for an adult pharaoh. In the summer of the year before last, sensational news spread around the world: the mummy of Hatshepsut, the first woman in history who could be called famous, had been found. Finding her was the solution to the greatest mystery, a mixture of thrilling adventure in the spirit of Indiana Jones and crime drama.

In Ancient Egypt, royal power was transferred in a rather original way: inheritance went through the female line - but the pharaohs were men. That is, the king became the son-in-law of the pharaoh, the husband of the princess - the daughter of the main royal wife (also, in turn, a bearer of royal blood). That is why the sons of the pharaohs were forced to marry their sisters - in order to inherit the throne. Through marriage, a dignitary or commander could also become a pharaoh. So power was passed on through daughters - but bypassing daughters, since tradition and religion stated that women could not rule. Therefore, the story of Hatshepsut, the woman who became pharaoh, is completely unique.

Hatshepsut's grandfather, probably (there are still many blank spots in the history of the New Kingdom, and therefore it is difficult to say anything for sure), was the founder of the 18th dynasty, Ahmose I, who expelled from Egypt the formidable Hyksos, who two centuries earlier had captured the north of the Nile Valley. The son of Ahmose Amenhotep I had no sons, and therefore the next pharaoh was a certain military leader Thutmose, who married Princess Ahmose, probably the daughter of Ahmose I. From this marriage Thutmose had a daughter, Hatshepsut, and from his second wife, Queen Mutnofret (possibly also the royal daughters) - heir to Thutmose II.

By marrying his sister Hatshepsut, Thutmose II gained the right to the throne. And she seemed to repeat the fate of her mother - the royal couple had only a daughter, while the second wife of Pharaoh Isis gave birth to an heir.

But then this story, until now quite traditional, ceases to be so. For a long time it was believed that when Thutmose II left this world (from heart problems, as determined thousands of years later by a computer tomograph), his heir Thutmose III was still very young. And therefore, Queen Hatshepsut, according to tradition, became regent for the child. However, today it is known from ancient inscriptions: even during the life of his father, Thutmose III was already a priest of Amun-Ra in the Karnak Temple in Thebes. That is, when the pharaoh died, the heir was unlikely to be a child. However, his stepmother somehow mysteriously managed to become a regent under the probably young, but no longer a minor, king.

Her Majesty the King. This was just the beginning - then traditions began to collapse like a house of cards. At first, Hatshepsut still ruled on behalf of her stepson - but soon the reliefs began to depict how the regent performed purely royal functions: offering gifts to the gods, ordering obelisks made of red granite. And a few years later she officially becomes a pharaoh.

Thutmose III was relegated to the status of co-ruler and, it seems, was not allowed to reach real power. Hatshepsut was the full-fledged mistress of Egypt for no less than 21 years. What made the Egyptian woman abandon the traditional role of regent? A crisis? Will of Amon-Ra? Thirst for power? It is difficult to understand her motives today. But it is no less difficult to understand how Hatshepsut managed for twenty years to prevent her adult stepson from coming to power, who had an undeniable advantage over his stepmother from the point of view of the ancient Egyptians - gender.

It seems unlikely that Hatshepsut usurped the throne by force. Although Thutmose III did not take part in state affairs, it was he who was “thrown” into resolving military conflicts. And it is unlikely that the queen would have risked putting at the head of the army someone from whom she had taken away power against her will.

This situation could be explained by the weakness and passivity of the opponent - but no! After the death of his stepmother, Thutmose III proved himself to be an unusually active ruler; he actively erected monuments and fought so successfully that he was later nicknamed the ancient Egyptian Napoleon. Over 19 years, Thutmose III conducted 17 military campaigns, including defeating the Canaanites at Megiddo, in what is now Israel - an operation that is still studied in military academies!

So, most likely, peace and harmony reigned between the stepson and stepmother - but one can only guess how Hatshepsut managed to make her defeated rival her ally. This woman was probably excellent at getting along with people, manipulating them, and intriguing them. And her talents, willpower and motivation were certainly extraordinary.

“No one knows what she was like,” says Egyptologist Katharina Roehrig. “I think she was an excellent strategist and knew how to pit people against each other so as not to destroy them, and not to die herself.” One way or another, Hatshepsut solved the problem with her co-ruler, but a more serious problem remained. Tradition and religion unanimously asserted that the pharaoh is always a man, and this probably made the queen’s position very precarious. Pharaoh Hatshepsut tried to resolve this issue in different ways.

PR campaign like a king. In written texts, the pharaoh did not hide her gender - we see many feminine endings. But in the images she clearly tried to combine the images of the queen and the king. On one seated statue made of red granite, Hatshepsut's body shape is female, but on her head there are symbols of male kings: a nemes - a striped headdress and a uraeus - a forehead figurine of a sacred cobra. On some reliefs, Hatshepsut appears in a traditional strict dress below the knees, but with legs spread wide apart - this is how kings were depicted in a walking pose. Hatshepsut planted visual images of a female pharaoh, as if accustoming the Egyptians to such a paradox.

But either the method did not bring the desired results, or Hatshepsut was convinced - one way or another, over time she changed her tactics. The pharaoh began to demand that she be depicted in a male guise: in a pharaoh's headdress, a pharaoh's loincloth, with a royal false beard - and no feminine features. Trying to justify her strange position, the female pharaoh calls on... the gods as allies. On the reliefs of the mortuary temple, Hatshepsut says that her accession to the throne is the fulfillment of a divine plan and that her father Thutmose I not only wanted his daughter to become king, but was even able to attend her coronation!

The reliefs also tell how the great god Amun appears before the mother of Hatshepsut in the guise of Thutmose I. He turns to the creator god Khnum, who creates a man from clay on a potter’s wheel: “So create her better than all other gods, blind her for me, this is my daughter, begotten by me.” Khnum echoes Amun: “Her image, when she takes the great post of king, will be worshiped more than the gods...” - and immediately gets to work. It is interesting that on Khnum's potter's wheel baby Hatshepsut is clearly a boy.

Pharaoh Hatshepsut became a great builder. Everywhere, from Sinai to Nubia, she erected and restored temples and shrines. Under her rule, masterpieces of architecture were created - four granite obelisks in the huge temple of the god Amun-Ra in Karnak. She commissioned hundreds of her own statues and immortalized in stone the history of the entire family, her titles, the events of her life, real and fictional, even her thoughts and aspirations. Her statement, carved on one of the obelisks in Karnak, is striking in its sincerity and poignancy: “My heart trembles at the thought of what people will say. What will those who look at my monuments say about my deeds years later?

But who was this powerful propaganda aimed at? For whom did the pharaoh write her sincere confessions and create myths? For priests? Nobles? Military? Officials? Gods? The future?

Humanist and vandal. One of the possible answers is suggested by Hatshepsut’s habit of referring to the lapwing, an inconspicuous swamp bird. In ancient Egypt, the lapwing was called "rehit", which in hieroglyphic texts usually means "common people". They, ordinary as lapwings on the Nile, were not taken into account by any of the pharaohs and did not influence politics in any way, although the word is often found in inscriptions. But Kenneth Griffin from the University of Swansea in Wales noticed that Hatshepsut used it much more often than other pharaohs of the 18th dynasty. A unique phenomenon, the scientist believes. Hatshepsut often used the form “my rekhit”, turning to ordinary people for support... Saying that her heart trembled at the thought of what people would say, the queen may have meant just rekhit - ordinary mortals.

After the death of Hatshepsut, her stepson came to power. And he did not only engage in conducting successful military campaigns. Thutmose III suddenly became interested in methodically erasing the reign of his stepmother from history. Almost all images of Hatshepsut and even her name were systematically chipped off from temples, monuments and obelisks. The pharaoh attacked the traces of the existence of King Hatshepsut no less zealously than he attacked the Canaanites in Megiddo. Its inscriptions on obelisks were covered with stones (which had an unplanned result - the texts were perfectly preserved).

At Deir el-Bahri on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Luxor, is the funeral temple of Hatshepsut Djeser Djeseru - “the holiest of the sacred.” The three-level structure, porticoes, wide terraces connected by ramps, the alley of sphinxes that have not reached us, T-shaped pools with papyrus and myrrh trees creating shade - all this makes Djeser Djesera one of the most beautiful temples in the world and the best building of Hatshepsut. According to the design of the architect (probably Senmut, supposedly Hatshepsut's favorite), the temple was to become the central place of cult of the queen. But under Thutmose III, her statues were broken here and thrown into a pit.

It would seem that Thutmose III acted in full accordance with the popular ancient Egyptian tradition of erasing the names of unloved predecessors from monuments. Well, how can we not recall the version about the unfortunate orphan who was bullied by his evil stepmother for many years? And historians succumbed to temptation - the hypothesis that Thutmose III exterminated the memory of Hatshepsut in revenge for her unscrupulous usurpation of royal power became very popular for many years. Conclusions about the personality of Hatshepsut herself were drawn accordingly. In 1953, archaeologist William Hayes wrote: "Soon... this vain, ambitious, unscrupulous woman would show herself in her true colors."

Who was bothered by the dead queen? However, in the 1960s, the heartbreaking story of family squabbles ceased to seem indisputable. It was established that the persecution of Pharaoh Hatshepsut began at least twenty years after her death! Such anger is somewhat strange - twenty years of endurance!

There is another mystery - for some reason the “avenger” did not touch those images where Hatshepsut appears as the king’s wife. But all those where she declares herself to be a pharaoh, his workers went through with chisels. This is neat, targeted vandalism. “The destruction was not carried out under the influence of emotions. It was a political calculation,” said Zbigniew Szafranski, head of the Polish archaeological mission in Egypt, who has been working at the Hatshepsut mortuary temple since 1961. Indeed, today it seems more logical to assume that Thutmose III acted based on political interests. Perhaps it was necessary to confirm the legal right of his son Amenhotep II to the throne, which was also claimed by other members of the royal family. Descendants of Hatshepsut? Women?

Escaped Mummy. In 1903, the famous archaeologist Howard Carter discovered in the twentieth tomb from the Valley of the Kings (number KV20) two sarcophagi with the name Hatshepsut - apparently, from among the three that the queen herself had prepared in advance for herself. However, there was no mummy there.

But in a small tomb next door, KV60, Carter saw “two heavily exposed female mummies and several mummified geese.” One mummy, a smaller one, lay in the sarcophagus, the other, a larger one, lay right on the floor. Carter took the geese and closed the tomb.

Three years later, the mummy from the sarcophagus was transported to the Cairo Museum, having established that the inscription on the coffin indicated the nanny of Hatshepsut. And the second mummy remained on the floor. She seemed to be a simple slave - too uninteresting to be placed anywhere. KV60a (under this number the mummy was entered into the registries) set off on an eternal journey, having neither a coffin, nor clothes, nor figurines of servants, nor a headdress, nor jewelry, nor sandals - nothing that a noble woman should take.

Arm bent at the elbow. Years passed, everyone completely forgot about the mummy left on the floor, and even the road to the KV60 tomb was lost. It was found again in 1989 by scientist Donald Ryan, who came to study several small, undecorated graves. He also included the KV60 in the application.

Having descended into the tomb, the scientist immediately realized that in ancient times it had been barbarically plundered. “We found a broken fragment of a coffin with a face and a grain of gold that had all been scraped off,” he recalls. That is, thieves could easily take away the sarcophagus and all the decorations of the mummies, if any. And in the next room, Ryan discovered a huge heap of fabric and a pile of “edible mummies” - food folded into bundles, which was given to the deceased with him on his journey through eternity. But what interested Ryan most was the mummy's left hand, still lying on the floor. The arm was bent at the elbow - and some scientists believe that only royalty was buried this way during the 18th Dynasty. And the longer Ryan studied the mummy, the more convinced he became that it was an important person. “She was mummified to perfection,” he recalls. “But there were no clues to somehow identify her.”

And yet, it seemed wrong to the scientist to leave the mummy, whoever it was, lying on the floor in a heap of rags. Ryan and his colleague cleaned up the tomb, ordered a modest coffin from a carpenter, lowered the stranger into a new box and closed the lid. The mummy spent almost two more decades in the tomb and in obscurity - until a new study began on the secret of Hatshepsut.

It's all about the tooth. The study was launched by Zahi Hawass, director of the program for the study of Egyptian mummies and secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities of Egypt. First, Hawass collected all the unidentified female mummies of the 18th Dynasty, presumably related to the royal family. There were four of them, among them both inhabitants of the tomb KV60. The scientist, however, was sure that the KV60a mummy had absolutely nothing to do with it. She did not have a regal posture at all and, as the archaeologist wrote, “her huge breasts hung down” - rather, she could have been a nurse. But nevertheless, she, along with others, was examined on a CT scanner, establishing her age and cause of death.

Dentists determined that it was a second molar that was missing part of the root. And the large mummy from the floor of tomb KV60 had a root without a tooth in the upper jaw on the right. Measurements were taken - the root and tooth were completely consistent with each other!

Today the KV60a mummy is on display in the Cairo Museum. The tablet is written in Arabic and English that this is Hatshepsut, Her Majesty the King, who has finally been reunited with her large family - the pharaohs of the New Kingdom. In the era of the XXI dynasty, around 1000 BC, her body could have been transferred to the nanny’s tomb by the high priests of Amun in order to protect the mummy from thieves - members of the royal family were often hidden in secret graves.

CT scanners have already refuted the hypothesis that Hatshepsut was killed by her stepson. A large woman, KV60a, died from an acute and severe infection caused by an abscess in her tooth; in addition, she probably suffered from bone cancer and possibly diabetes.

What if the tooth from the box did not belong to Hatshepsut? The first DNA tests are still inconclusive. But new research should provide a more definitive verdict.

Against the backdrop of deserted hills in Deir el-Bahri stands the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut - one of the most beautiful and majestic temples in the world. They tried to destroy the reliefs on its porticos - but today they tell us about the reign of a female pharaoh.

Scene on the wall at Deir el-Bahri: a man drags a myrrh tree to the Egyptian ships that sailed along the Red Sea to the country of Punt (about which little is still known). Around 1470 BC, Hatshepsut sent traders there.

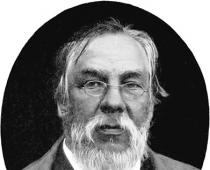

The woman pharaoh Hatshepsut spent her whole life “searching for her image” - deciding in what form she would appear before the people and descendants. In the photo she is wearing a pharaoh's headdress, but the slight roundness and graceful chin indicate that she is a woman (an early version).

In the guise of a sphinx, she already looks more like a man - with a lion's mane and a royal false beard.

Stepson of Hatshepsut Thutmose III.

Having seized power, Hatshepsut assigned a minor role to her stepson Thutmose III - this is evidenced by the reliefs on the walls of the Red Sanctuary at Karnak. In a scene depicting a religious celebration, Hatshepsut stands before Thutmose III, both dressed as pharaohs, but the titles above describe them as one person.

Red Sanctuary at Karnak.

The mortuary temple of Hatshepsut is framed by the steep hills of the Western Desert. Behind the highest ridge a giant chasm begins. This is the Valley of the Kings - the cemetery of the pharaohs, where the entrance to the tomb of Hatshepsut is located. Her father, apparently, was the first of the pharaohs to establish his final refuge in the valley. The tradition he established lasted for more than four centuries.

Nurse of Hatshepsut.

Hatshepsut.

Where did Hatshepsut's mummy go? A century ago, two unidentified female mummies were discovered in a small tomb. Probably the priests hid them from thieves. Recent tests have shown that a tooth found in a box bearing the name Hatshepsut exactly matches a socket in the jaw of a larger mummy. It looks like the Pharaoh's secret is almost solved.

Recent tests have shown that a tooth found in a box bearing the name Hatshepsut exactly matches a socket in the jaw of a larger mummy. It looks like the Pharaoh's secret is almost solved.

In the temple of the god Amon-Ra in Karnak, tourists can personally see that after the death of Hatshepsut (at least twenty years later), her images in the guise of a pharaoh began to be destroyed everywhere. Who did the queen begin to interfere with two decades after her death? Perhaps the children of the new pharaoh - if the direct descendants of Hatshepsut lay claim to the throne.

The Obelisk of Hatshepsut, made from a single piece of granite, rises thirty meters above the ruins of Karnak. Defying all attempts to erase the queen from history, the majestic monument survived and today is the tallest monument of its kind in Egypt.

Hatshepsut (1490/1489-1468 BC, 1479-1458 BC or 1504-1482 BC) - female pharaoh of the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt from the XVIII dynasty. Before her accession, she bore the same name (Hatshepsut, that is, “Who is in front of the noble ladies”), which was not changed upon accession to the throne. She remained in history as a builder, a good military leader and a smart politician.

Hatshepsut completed the restoration of Egypt after the Hyksos invasion and erected many monuments throughout Egypt. She is one of the first famous women in world history, and, along with Thutmose III, Ramesses II, Akhenaten, Tutankhamun and Cleopatra VII, one of the most famous Egyptian rulers. Besides Hatshepsut, only four women can be found among the sovereign rulers before the conquest by Alexander the Great - Merneit (Meritneit), Nitokris (Neitikert) at the end of the Old Kingdom, Nefrusebek (Sebeknefrura) at the end of the Middle Kingdom and Tausert at the end of the 19th Dynasty. Unlike Hatshepsut, they all came to power at critical periods in Egyptian history.

According to a quote from an Egyptian priest-historian of the 3rd century BC. e. Manetho, according to Josephus, she ruled for 21 years and 9 months, but Sextus Julius Africanus gives the same quote, which states that Hatshepsut ruled for all 22 years. In the surviving excerpts from the Annals of Thutmose III, the chronicle of the court military chronicler Tanini, Thutmose III's first campaign as sole ruler (during which the famous Battle of Megiddo took place) refers to the spring of the 22nd year of the nominal reign of the pharaoh, which clearly confirms the information of Manetho .

The long and middle chronologies of ancient Egyptian history common in scientific literature date the reign of Hatshepsut to 1525-1503 BC, respectively. e. and 1504-1482 BC. e. The short chronology accepted in modern research dates the reign of Queen Hatshepsut to 1490/1489-1468 BC. e. or 1479-1458 BC e. The difference of 10 years is explained by the fact that the reign of Thutmose II in the royal lists is estimated at 13/14 years, but is practically not reflected in material monuments, on the basis of which its duration is reduced to 4 years (accordingly, the period of time between the ascension to the throne of Thutmose I and Hatshepsut can be estimated at 25 or 14 years old).

Queen Hatshepsut was the daughter of the third pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, Thutmose I, and Queen Ahmes (Ahmose). Thus, she was the granddaughter of the founder of the New Kingdom, Pharaoh Ahmose I. During the life of her father, Hatshepsut became the “Wife of God” - the high priestess of the Theban god Amon.

Hatshepsut had only one full sister, Nephrubiti, as well as three (or four) younger half-brothers, Uajmose, Amenmose, Thutmose II and, possibly, Ramos, the sons of her father Thutmose I and Queen Mutnofret. Wajmose and Amenmose, Hatshepsut's two younger brothers, died in infancy. Therefore, after the death of Thutmose I, she married her half-brother Thutmose II (the son of Thutmose I and the minor queen Mutnofret), a cruel and weak ruler who ruled for only less than 4 years (1494-1490 BC; Manetho counts as many as 13 years his reign, which is most likely wrong). Thus, the continuity of the royal dynasty was preserved, since Hatshepsut was of pure royal blood. Experts explain the fact that Hatshepsut subsequently became a pharaoh by the rather high status of women in ancient Egyptian society, as well as by the fact that the throne in Egypt passed through the female line. In addition, it is generally believed that such a strong personality as Hatshepsut achieved significant influence during the lifetime of his father and husband and could, in fact, rule in place of Thutmose II.

Thutmose II and Hatshepsut had as their main royal wife a daughter, Nefrura, who bore the title of "God's Consort" (high priestess of Amun) and was depicted as the heir to the throne, and possibly Merythra Hatshepsut. Some Egyptologists dispute that Hatshepsut was the mother of Merythra, but the opposite seems more likely - since only these two representatives of the 18th dynasty bore the name Hatshepsut, it may indicate their blood relationship. Images of Nefrura, whose tutor was Hatshepsut's favorite Senmut, with a false beard and curls of youth are often interpreted as evidence that Hatshepsut was preparing an heiress, a “new Hatshepsut.” However, the heir (and later co-ruler of Thutmose II) was still considered the son of her husband and concubine Isis, the future Thutmose III, married first to Nefrur, and after her early death - to Merythra.

After ascending the throne, Hatshepsut was proclaimed pharaoh of Egypt under the name Maatkara Henemetamon with all the regalia and the daughter of Amun-Ra (in the form of Thutmose I), whose body was created by the god Khnum himself. The power of the queen, which relied primarily on the priesthood of Amun, was legitimized with the help of the legend of theogamy, or “divine marriage,” during which the god Amun himself allegedly descended from heaven to the earthly queen Ahmes in order to, taking the form of Thutmose I, conceive “his daughter” Hatshepsut. In addition, the ceremonial inscriptions stated that the queen was chosen as heir to the Egyptian throne during the lifetime of her earthly father, which was not true. Subsequently, official propaganda constantly used the legend of Hatshepsut's divine origin to justify her stay on the throne.

Having accepted the title of pharaoh, Hatshepsut began to be depicted wearing a hat hat with a uraeus and a false beard. Initially, statues and images of Hatshepsut represented her with a female figure, but in male clothing, and in later analogues her image was finally transformed into a male one. The prototype of such images of Hatshepsut can be considered the few surviving statues of Queen Nefrusebek, which are also characterized by a combination of male and female canons. Nevertheless, in the inscriptions on the walls of the temples, the queen continued to call herself the most beautiful of women and refused one of the royal titles - “Mighty Bull”.

Since the pharaoh in Egypt was the incarnation of Horus, he could only be a man. Therefore, Hatshepsut often wore men's clothes and an artificial beard at official ceremonies, but not necessarily: individual statues of the queen, like those exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, continue to depict her in her previous form - in tight-fitting women's clothing, but in a nemes cape and without a false beard.

Woman - Pharaoh - Builder

The reign of Hatshepsut marked unprecedented prosperity and rise in Egypt. Of all the areas of her state activity, Hatshepsut showed herself primarily as a pharaoh-builder. Only Ramses II Meriamon built more than it (who, by the way, put his name on the monuments of his predecessors). The queen restored many monuments destroyed by the Hyksos conquerors. In addition, she herself actively led the construction of temples: the so-called. Hatshepsut's "Red Sanctuary" for the ceremonial boat of the god Amun; relief images on the walls of the sanctuary, recently completely restored from scattered blocks, are dedicated to the co-rule of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, as well as the legitimization of her sole power. Here, in Karnak, by order of the queen, giant granite obelisks were installed, the VIII pylon was erected in the temple of Amon, the sanctuary of Amun-Kamutef was built, and the temple of Amon’s wife, the goddess Mut, was significantly expanded. The two obelisks of Hatshepsut (29.56 m high) next to the pylon of the Temple of Amun-Ra in Karnak were the tallest of all those built early in Egypt until they were laid with stone masonry by Thutmose III (one of them has survived to this day).

Still, the most famous architectural monument of Hatshepsut’s time is the beautiful temple at Deir el-Bahri in the remote western part of Thebes, which in ancient times bore the name Djeser Djeseru - “The Most Sacred of the Sacred” - and was built over the course of 9 years - from the 7th (presumably 1482 BC) to the 16th (1473 BC) year of the queen's reign. Its architect was Senmut (?), and although the temple largely replicated the nearby temple of the Middle Kingdom pharaoh Mentuhotep I, its majestic columns amaze the imagination even today. At one time, this temple was unique in many ways, demonstrating the impeccable harmony of the architectural complex 1000 years before the construction of the Parthenon in Athens.

Djeser Djeseru consisted of three large terraces, decorated with porticoes with snow-white limestone proto-Doric columns. The temple terraces in the center were divided by massive ramps leading upward to the temple sanctuary; they were decorated with numerous brightly painted Osiric pilasters of the queen, her kneeling colossal statues and sphinxes, many of which are kept in the collections of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. A long alley of polychrome sandstone sphinxes of the queen, lined with myrrh trees brought from Punt, led to the first of the terraces. The sphinxes were located on both sides of a road approximately 40 meters wide, leading from the lower terrace of the temple to the border of the desert and irrigated fields of the Nile Valley, where the giant pylon was erected.

In addition to the queen herself, the complex at Deir el-Bahri was dedicated to Amun-Ra, the deified father of Hatshepsut Thutmose I, the guide to the afterlife Anubis and Hathor Imentet - the mistress of the necropolises of Western Thebes and the great protector of the dead. In front of the temple itself, a garden of exotic trees and shrubs was laid out, and T-shaped pools were dug.

The unique reliefs of the temple in Deir el-Bahri, stunning with the highest level of their execution, tell the story of the main events of the reign of Hatshepsut. Thus, on the walls of the portico of the lower terrace, the delivery of the obelisks of the queen from Aswan to Karnak and ritual scenes associated with the idea of unifying Upper and Lower Egypt are depicted. The reliefs of the second terrace tell about the divine union of Hatshepsut's parents - the god Amun and Queen Ahmes and about the famous military-trading expedition to the distant country of Punt, equipped by the queen in the 9th year of her reign. The idea of the unity of both lands is found once again on the railings of the ramp connecting the second and third terraces of the temple. The lower bases of this staircase are decorated with sculptures of a giant cobra - the symbol of the goddess Wadjet - whose tail rose up the top of the railing. The head of the snake, personifying the patroness of Lower Egypt, Wadjet, is framed with its wings by the falcon Horus of Bekhdet, the patron god of Upper Egypt.

Along the edges of the second terrace are the sanctuaries of Anubis and Hathor. Both sanctuaries consist of 12-column hypostyle halls located on the terrace and interior spaces going deep into the rock. The capitals of the columns of the sanctuary of Hathor were decorated with gilded faces of the goddess, directed to the west and east; On the walls of the sanctuary, Hatshepsut herself is depicted drinking divine milk from the udder of the sacred cow Hathor. The upper terrace of the temple was dedicated to the gods who gave life to Egypt, and to Hatshepsut herself. On the sides of the central courtyard of the third terrace are the sanctuaries of Ra and Hatshepsut's parents - Thutmose I and Ahmes. At the center of this complex is the sanctuary of Amun-Ra, the Holy of Holies, the most important and most intimate part of the entire Deir el-Bahri temple.

Near Deir el-Bahri, also west of Thebes, Hatshepsut ordered the construction of a special sanctuary in Medinet Abu on the site of the sacred hill of Djeme, under which the serpent Kematef, the embodiment of the creative energy of Amon-Ra, rested at the beginning of time. However, Hatshepsut was actively building temples not only in Thebes, but throughout Egypt.

Famous are the rock temple erected by the queen in the future Speos Artemidos in honor of the lion-headed goddess Pakhet, as well as the temple of the goddess Satet on the island of Elephantine; in addition, architectural fragments with the name of the queen were discovered in Memphis, Abydos, Armant, Kom Ombo, El-Kab, Hermopolis, Kus, Hebenu. In Nubia, by order of the queen, temples were erected in the Middle Kingdom fortress of Buhen, as well as in a number of other points - in Sai, Dhaka, Semne and Qasr Ibrim, while many of the monuments of Hatshepsut may have been damaged during the sole reign of Thutmose III.

Military campaigns of Queen Hatshepsut

Under Hatshepsut, Egypt flourished economically. Classic slave relations were established and active trade was carried out. Around 1482/1481 BC e. it equipped an expedition of 210 sailors and five ships under the command of Nekhsi to the country of Punt, also known as Ta-Necher - “Land of God”. The location of the country of Punt has not been precisely established (most likely, the coast of East Africa in the Horn of Africa - the modern peninsula of Somalia). Contacts with Punt were interrupted during the Middle Kingdom, but they were vital, since Punt was the main exporter of myrrh wood. During the expedition, the Egyptians purchased ebony wood, myrrh wood, various incense, including incense (tisheps, ichmet, hesait), black eye paint, ivory, tame monkeys, gold, slaves and the skins of exotic animals from Punt. The reliefs of the temple at Deir el-Bahri present all the details of this campaign. The artists depicted in detail the fleet of Hatshepsut, the features of the landscape of Punt with forests of fragrant trees, exotic animals and houses on stilts. Also on the walls of the temple is a scene of recognition by the rulers of Punt (King Parehu and Queen Ati) of the formal authority of Hatshepsut.

For a long time it was believed that Hatshepsut, as a woman, could not conduct military campaigns, and her reign was extremely peaceful, which allegedly caused discontent in the army. However, the latest research has proven that she personally led one of the two military campaigns carried out during her reign in Nubia, and also controlled the Sinai Peninsula, the Phoenician coast, southern Syria and Palestine. In particular, the conduct of military campaigns by the queen is confirmed by the inscription in Tangur - a victory report carved on a rock in the area of the Second Cataract of the Nile. Moreover, Hatshepsut may have commanded Egyptian troops in a number of campaigns against rebellious Syrian and Palestinian cities. It is known that Hatshepsut admitted her stepson Thutmose to military service, which opened the way for him to become the first great warrior in history.

Death of Pharaoh Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut died around 1468 BC. e. Since she had not yet reached old age, versions of both the natural death and the violent death of the queen were put forward. However, a 2007 analysis of a mummy identified as Hatshepsut showed that she was approximately 50 years old at the time of death and died solely from illness (bone and liver cancer, exacerbated by diabetes)

There are two tombs belonging to Hatshepsut, but the queen's mummy was not found in either of them. It was long believed that Hatshepsut's mummy was either destroyed or moved to another burial site during the final years of the Ramesside reign, when tomb looting became widespread and the mummies of prominent New Kingdom rulers were reburied by priests led by Herihor.

Work on the first tomb of the queen began when she was the main royal wife of Thutmose II. The queen's early tomb is located in the rocks of Wadi Sikkat Taqa el-Zeid, south of the temple at Deir el-Bahri. However, she could not accommodate Hatshepsut, who became pharaoh, so work on it stopped, and the main tomb of Hatshepsut, KV20, was carved into the rocks of the Valley of the Kings. It was discovered in 1903 by Howard Carter. The queen's original plan, apparently, was to connect the tomb with the funeral temple at Deir el-Bahri with a grandiose tunnel, but due to the fragility of the limestone rocks, this idea was abandoned. However, the workers had already begun work on the passage, which was later turned into a vast burial chamber, where the mummy of the queen’s father, Thutmose I, was transferred from tomb KV38.

We do not know whether the queen herself was ever buried in the magnificent quartzite sarcophagus, which was found empty in this tomb. Thutmose III returned his grandfather's mummy to its original burial place, and it is believed that he may have moved his stepmother's mummy as well. Fragments of a wooden gilded sarcophagus, possibly belonging to Hatshepsut, were discovered in 1979 among scraps of shrouds and the remains of funerary goods in the unfinished tomb of the last pharaoh of the 20th dynasty, Ramesses XI (KV4).

In March 2006, at a lecture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, one of the leading experts in modern Egyptology, Dr. Zahi Hawass, said that the queen's mummy was discovered on the third floor of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, where it had been for several decades. This mummy, one of two found in a small tomb in the Valley of the Kings (KV60) and taken to Cairo in 1906, was until recently considered to be the mummy of a woman named Sat-Ra (Sitre), the queen's nurse, but not herself. Indirect evidence that the mummy belonged to a female pharaoh is the throne discovered in the tomb of Sat-Ra, the board game senet and ushabti with the name Hatshepsut.

Another contender for Hatshepsut's mummy was the mummy of an unknown queen of the New Kingdom, found in 1990 in tomb KV21. A wooden canopic box containing the entrails of Queen Hatshepsut was discovered in 1881 in an opened cache of royal bodies at Deir el-Bahri. Its ownership of the queen of the 18th dynasty is also disputed, since it could also have belonged to a noble woman of the 21st dynasty, whose name also sounded like Hatshepsut.

By order of Zaha Hawass, a genetic laboratory was placed near the museum in 2007, in which scientists from around the world had to test assumptions about which of the mummies really belonged to Queen Hatshepsut. As a result of a DNA analysis of mummies carried out by Cairo scientists, on June 26, 2007, the mummy from the tomb of Sat-Ra was officially identified as the body of Hatshepsut. Selecting from the abundance of surviving mummies of representatives of the 18th dynasty (for example, the mummy of the nephew and stepson of Queen Thutmose III was clearly identified), scientists settled on Hatshepsut’s grandmother Ahmose Nefertari, whose genetic material was compared with DNA from the mummy of her granddaughter.

The findings of the DNA analysis were confirmed by tomographic scanning, which proved that the tooth previously found in a small wooden box with a cartouche of Hatshepsut was precisely the missing tooth from the jaw of the KV60 mummy. This discovery was declared "the most important in the Valley of the Kings since the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb."

Persecution after the death of Queen Hatshepsut

It is a well-established idea that Thutmose III, setting out on a campaign against Syria and Palestine, which had withdrawn from submission to Egypt three years earlier, in 1472 BC. e., ordered the destruction of all information about the late Hatshepsut and all her images in revenge for the deprivation of his power, so for a long time practically nothing was known about this queen. In particular, the huge gilded obelisks at Karnak were covered with masonry or simply covered with sand, many images of the queen from the temple at Deir el-Bahri were destroyed or buried nearby, even the name Hatshepsut itself was excluded from the official temple lists of the pharaohs of Egypt. The name Hatshepsut was cut out from the cartouches and replaced with the names of Thutmose I, Thutmose II and Thutmose III, which was tantamount to a curse for the ancient Egyptian. Similarly, the pharaohs of the early 18th Dynasty erased all inscriptions belonging to the period of the hated Hyksos kings, Akhenaten persecuted names including the name of Amun (excluding the name of the god even from the cartouches of his own father Amenhotep III), and Horemheb, in turn, destroyed the name of the “Apostate of Akhetaten."