Just recently one could say about Grigory Dashevsky - “a living classic”. A teacher of Latin and the history of Roman literature, a creator of poetic palimpsests, a brilliant translator and essayist, a literary observer and an unusually handsome man, died two months before his half-century anniversary. After him, four collections of poetry remained (one of which was completely included in the other, and another one was destroyed due to the presence in it of parallel texts on German), many brilliant translations from German, English, French, unique lectures posted on the Internet. But, perhaps, Dashevsky’s most important legacy is the uninterrupted relationship between education, philosophy and poetry.

Traditions of classical philology

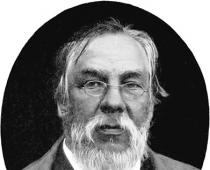

The biography of Grigory Dashevsky is laconic, like the inscriptions on ancient monuments, and could belong to the century before last. A native Muscovite (born February 25, 1963, died December 17, 2013), a graduate of the Faculty of Philology of Moscow State University. He first taught Latin, then the history of Roman literature to philology students of his alma mater, interned in Paris and Berlin, and until his death worked at the Department of Classical Philology of the Russian State University for the Humanities. Constant literary reviews in the far from philological Kommersant made it possible to rank Dashevsky among the most brilliant Russian critics. His discussions about the rights of people with disabilities caused heated debates in society, and video recordings of lectures and draft translations

Dov were transmitted among students. Dashevsky belonged to a rare type of poet in Russia, gravitating not to bohemian, but to university traditions, although he himself called himself a student of Timur Kibirov.

Literary scholars call Dashevsky's poems palimpsests. This ancient term literally meant parchment from which the old text had been erased and a new one written over it. Poetic palimpsests are a way of interaction between tradition and modernity, the highest manifestation of authorship. Palimpsests are not translations or direct quotations of the classics, they are its development and continuation, a kind of poetic roll call. In Dashevsky's poetry one can find elements of pop and intellectual banter, his poetic

These images erase the boundaries of eras and spaces - they are simultaneously from another dimension and from a neighboring courtyard, taking on the harsh significance of an ancient amphitheater, and the minted minimalism of Latin is organically transformed into street slang, raising it to the heights of the spirit.

Dashevsky's translations of philosophers and writers of the twentieth century speak, first of all, about the theme of interaction between the individual and the totalitarian system, which unexpectedly and paradoxically appeared in his poem "Henry and Semyon."

Last years Dashevsky was treated in the fight against a debilitating disease, but he complained only of decreased performance. Awards received during his lifetime included two shortlistings and one Andrei Bely Prize, the Maurice Maxwahe Prize

ra and Diploma from the Soros Institute. Dashevsky’s main legacy is his invaluable contribution to poetry and literary criticism and the uninterrupted tradition of the relationship between philosophy, poetry and education.

Love and death

Grigory Dashevsky cannot be classified as an idol whose names are well known. His poetry is not at all easy to understand, but it fascinates even readers brought up on literature of a completely different kind. In these poems there are no hypnotizing rhythms and musical harmonies, a flow of visual images and an appeal to common and generally understood truths. In addition, the meter of versification is unusual for Russian poetry, although it is quite trivial for its forgotten classical prototypes. At the heart of the title for Dashevsky's creativity

about the poem "Quarantine" ("Quiet Hour") - the poetry of Catullus, who, in turn, translated love lyrics Sappho. Sappho’s work describes the heroine’s state, blurring the line between love and death; in Catullus, through irony, you can hear the fading heartbeat, and Dashevsky’s hero is a teenager looking at the nurse with a mixture of lust and fear of reading a gloomy verdict in her eyes. The twin embryos included in the quote, who may be born girls, and they will be “not allowed to go to China,” the atmosphere of fantasy and the incorrectness of speech in “Martians in the General Staff,” the “Cheryomushkin neighbor” who stopped seeing what she saw, make one clearly feel the fine line between being and non-being, life and death, reality and illusion

y. Dashevsky's latest publication is an essay on Robert Frost and a translation of his iconic poem "Winter Forest", which reproduces with filigree precision both poetic form and deep content, especially "the most famous repetition of English poetry" in the finale, which brings together the interconnection of the desire for peace, sense of duty and the cold reality of existence.

It is noteworthy that the last creation of Grigory Dashevsky, made, according to rumors, in the intensive care ward, was a translation of Elliott’s “Ash Wednesday” with a request to teach “pity and indifference,” in which the last two lines remained unfinished with a request to pray for us now and at the hour of death : "Pray for us now and at the hour of our death."

On December 17, Grigory Dashevsky, a poet, translator and literary critic, died in a Moscow hospital after a long and serious illness. Having achieved recognition in all these areas of literature, he remained a man of such extraordinary modesty that the deserved veneration sometimes seemed inappropriate. He was only 49 years old.

Grigory Mikhailovich Dashevsky, as happens with the best in culture, came from classical philology: he studied and taught a little at Moscow State University, and a lot at the Russian State University for the Humanities, whose graduates became spreaders of the fame of their brilliant teacher. Dashevsky remained an antique in his original poetic work, which is convenient to say in other people’s words: “ Most of Dashevsky’s poems are “translations” of Latin poems, accurate in meaning, but altered so that their language is certainly Russian, and not a translation, in which there is always an admixture of foreignness.”

In poetry, Grigory Dashevsky was not associated with any literary movement- perhaps because I wrote very little. Nevertheless, Dashevsky’s poetic voice was very recognizable: all his devoted readers and grateful critics unanimously speak about this. The thesis about recognition may seem paradoxical when applied to a poet, whose manner is based on the ability to master someone else's style and subtly parody it. However, this is not a unique case in Russian poetry: one of Dashevsky’s teachers can be called Timur Kibirov (the latter dedicated a poem to the younger poet, antithetically rhyming “Dashevsky Grisha” with “I hear from a simulacrum”). Only Kibirov’s soulful intonation, which wraps any borrowed line in a signature warmth, has turned into Dashevsky’s intimacy of a completely different kind - the intimacy of the ultimate state in which a person is alone with himself. Mastering these extreme mental manifestations, familiar to everyone, but special to everyone, Dashevsky made the lyrical characters of his poems a Cheryomushkin maniac, a teenager watching a nurse, or a lover, at the peak of an intimate frenzy, looking at himself with frightening detachment.

Dashevsky did not need post-Kibirov centon poetry in order to build a common emotion on the foundation of cultural closeness with his contemporary. As the poet himself said, analyzing the poems of Maria Stepanova, an author from a close poetic generation, “quotes do not serve as a password for some circle, but<...>therefore they require only the most fleeting and weak reaction - “oh, something familiar.” According to Dashevsky, in modern literature, “clinging to recognizable quotes, meters, images in popular poems comes largely from the fear of reality, from the fear of being among strangers, from the fear of admitting that one is already among strangers. There are no more quotations: no one has read what you have; and even if you read it, it doesn’t bring you closer.” The meaning of stylistic borrowings (in particular, ancient ones) from Dashevsky is to highlight with them that very ultimate experience. The focus of his attention is not on the general read - cozy and safe, but on the extremely personal felt - secret, forbidden, and therefore unsafe. The most intimate fragments of experience, conveyed in quotative language, became outwardly impersonal (the poet himself said that romantic - egocentric - poetry ended after Brodsky), and therefore general, like a collective unconscious. Reading Dashevsky’s poems, you feel with horror and trepidation of self-knowledge: the Cheryomushkin maniac is a little bit of you too.

It is paradoxical how, with such lyrical tension, which not everyone will be ready to share, and at the same time hermetic sophistication, designed for subtle connoisseurs, Dashevsky’s poetry was widely loved. Having overcome the quotation, she herself entered the quotation background, and any real reader of modern poetry knew Frau has twins inside who argue: What if China is behind the walls of the peritoneum? / What if we are girls? But they can't go to China. Or these sapphic stanzas:

The one braver than Sylvester Stallone or

his photos above the pillow,

who looks into the gray eyes of nurses

without asking or fear,

and we are looking for a diagnosis in these pupils

and we don’t believe that under the starched robe

almost nothing, what is there at most

bra and panties.

Quiet hour, oh boys, has exhausted you,

in a quiet hour you chew on the duvet cover,

during quiet times we check more thoroughly

There are bars in the windows.

Unlike poetry, Dashevsky was prolific in translations and journalism, which became not only separate areas of application of his talent, but also the poet’s bread (for which we cannot but thank the Kommersant Publishing House). As an author of periodicals, Dashevsky was extremely responsible: you will not find notes or reviews from him without an independent and clear thought - thanks to which Dashevsky easily became the best modern Russian literary critic. The same applied to translations, which he seemed to choose not at all on a poetic whim, but based on the criterion of intellectual equality. Dashevsky translated Brodsky's essays, Nabokov's literary lectures, the biographical work of Aldous Huxley (together with Viktor Petrovich Golyshev), and the stories of Truman Capote. Not only in journalism, but also in Dashevsky’s translations, high degree social responsibility, which is not characteristic of every writer. Dashevsky translated Hannah Arendt, a prominent post-war thinker famous for her analysis of the origins and nature of totalitarianism and fascism. And Arendt Dashevsky criticized other people’s bad translations precisely for intellectual negligence, which alone was capable of changing the meaning of a sharp text to the opposite.

The favorite author of the translator Grigory Dashevsky was the French philosopher and anthropologist Rene Girard (still alive, he is 89 years old). At the same time an academician and a rebel, Girard managed to become a bone in the throat even of his rebellious generation: he developed the ideas of structuralism to criticize the structuralists, and turned leftist ideology in a conservative direction so suddenly that he shocked the French left. Dashevsky translated two of Girard's main books: Violence and the Sacred and The Scapegoat; both develop the philosopher's main idea that the tradition of sacrifice - collective violence against an individual - lies at the basis of all human culture. Girard shows that the same mechanisms that triggered the persecution of Jews in our era also underlay archaic myths: when something is unsettled in a group, you need to find an extreme person to take out your fears on him - and then (in the case of a myth) and deify him, thanking him for his salvation from troubles, purchased at the cost of his life.

The biography of Grigory Dashevsky is laconic, like the inscriptions on ancient monuments, and could belong to the century before last. A native Muscovite (born February 25, 1963, died December 17, 2013), a graduate of the Faculty of Philology of Moscow State University. He first taught Latin, then the history of Roman literature to philology students of his alma mater, interned in Paris and Berlin, and until his death worked at the Department of Classical Philology of the Russian State University for the Humanities. Constant literary reviews in the far from philological Kommersant made it possible to rank Dashevsky among the most brilliant Russian critics. His discussions about the rights of people with disabilities caused heated debates in society, and video recordings of lectures and draft translations were transmitted among students. Dashevsky belonged to a rare type of poet in Russia, gravitating not to bohemian, but to university traditions, although he himself called himself a student of Timur Kibirov.

Literary scholars call Dashevsky's poems palimpsests. This ancient term literally meant parchment from which the old text had been erased and a new one written over it. Poetic palimpsests are a way of interaction between tradition and modernity, the highest manifestation of authorship. Palimpsests are not translations or direct quotations of the classics, they are its development and continuation, a kind of poetic roll call. In Dashevsky’s poetry one can find elements of pop and intellectual banter, his poetic images erase the boundaries of eras and spaces - they are simultaneously from another dimension and from a neighboring courtyard, acquiring the harsh significance of an ancient amphitheater, and the minted minimalism of Latin is organically transformed into street slang, raising it to the heights of the spirit.

Dashevsky's translations of philosophers and writers of the twentieth century speak, first of all, about the theme of interaction between the individual and the totalitarian system, which unexpectedly and paradoxically appeared in his poem "Henry and Semyon."

Dashevsky's last years were spent fighting a debilitating disease, but he complained only of decreased performance. Awards received during his lifetime included two shortlistings and one Andrei Bely Prize, the Maurice Maxvacher Prize and the Soros Institute Diploma. Dashevsky’s main legacy is his invaluable contribution to poetry and literary criticism and the uninterrupted tradition of the relationship between philosophy, poetry and education.

Love and death

Grigory Dashevsky cannot be classified as an idol whose names are well known. His poetry is not at all easy to understand, but it fascinates even readers brought up on literature of a completely different kind. In these poems there are no hypnotizing rhythms and musical harmonies, a flow of visual images and an appeal to common and generally understood truths. In addition, the meter of versification is unusual for Russian poetry, although it is quite trivial for its forgotten classical prototypes. The title poem for Dashevsky’s work, “Quarantine” (“Quiet Hour”), is based on the poetry of Catullus, who, in turn, adapted the love lyrics of Sappho. Sappho’s work describes the heroine’s state, blurring the line between love and death; in Catullus, through irony, you can hear the fading heartbeat, and Dashevsky’s hero is a teenager looking at the nurse with a mixture of lust and fear of reading a gloomy sentence in her eyes. The twin embryos included in the quote, who may be born girls, and they will be “not allowed to go to China,” the atmosphere of fantasy and the incorrectness of speech in “Martians in the General Staff,” the “Cheryomushkin neighbor” who stopped seeing what she saw, make one clearly feel the fine line between being and non-being, life and death, reality and illusion. Dashevsky's latest publication is an essay on Robert Frost and a translation of his iconic poem "Winter Forest", which reproduces with filigree precision both poetic form and deep content, especially "the most famous repetition of English poetry" in the finale, which brings together the interconnection of the desire for peace, sense of duty and the cold reality of existence.

It is noteworthy that the last creation of Grigory Dashevsky, made, according to rumors, in the intensive care ward, was a translation of Elliott’s “Ash Wednesday” with a request to teach “pity and indifference,” in which the last two lines remained unfinished with a request to pray for us now and at the hour of death : "Pray for us now and at the hour of our death."

Translator of Nabokov and Brodsky died after a long illness

On the morning of December 17, the poet, translator and one of the best literary critics in Russia, Grigory Dashevsky, died in therapy after a serious liver disease. In the fall of 2013, he was admitted to the hospital; blood was needed for the operation, as the poet’s friends and colleagues wrote on Facebook. But at the end of November, doctors admitted that the operation was impossible. The poet did not live to see his anniversary for only two months.

Grigory Dashevsky

Grigory Mikhailovich Dashevsky would have turned 50 on February 25. He was born in Moscow and graduated from the Faculty of Philology of Moscow State University in 1988. Patient by nature, Dashevsky taught at school for two years Latin language, later taught a course on the history of Roman literature at his native philological department. Grigory Dashevsky lived in France for some time, and in the mid-90s he trained in Berlin.

The first book of his poems, “Papier-mâché,” appeared in 1989, then “Change of Poses,” “Henry and Semyon,” and “The Duma of Ivan-Tea” were published. Dashevsky translated from English, French and German, taught Latin and ancient Roman literature. In his translations, the world saw books by Nabokov, Brodsky, Huxley and Warren. For the translation of "The Scapegoat" French philosopher Rene Girard Grigory Dashevsky received the Maurice Waxmacher Prize in 2010, and in 2011 he was awarded the independent Andrei Bely Prize. Grigory Mikhailovich also managed to be a publicist - he worked as a columnist for the Kommersant newspaper and was the editor of the Necessary Reserve magazine. Dashevsky was rightfully considered one of the best Russian critics in literature. “Dashevsky, in his criticism, seems to be trying to answer the question of how poetry is possible if the word poet itself “sounds too sublime, absurd, archaic,” and by calling himself a poet, a person either tells us that “he has no place in the world.” , or that he lives in a vanished world,” writes Alexander Zhitenev about his manner.

Dashevsky translated everything - prose, journalism and poetry. One of his most striking works is a translation of Robert Frost's most popular poem in Great Britain, “Stopping by a Wood on a Snowy Evening.” The first quatrain in translation sounds like this:

Whose forest do I think I know:

Its owner lives in the village.

He won't see how snowy

I stand and look at the forest.

Grigory Dashevsky created this masterpiece literally a month before his death - in October 2013.

When Ilya Segalovich died in July of this year, Dashevsky wrote on Facebook: “I am now reading responses to the death of Ilya Segalovich (whom I am very sorry that I was not acquainted with) - and there is no difference from what I heard about him before, when he was alive. It seems that even during his lifetime he was visible to people as clearly as a person is usually shown to us only by the funeral aggravation of feelings.” Now we are saying the same thing about Grigory Dashevsky.

He translated from German, English, French, Latin; his translations included texts by Hannah Arendt, Robert Penn Warren, Aldous Huxley, Catullus, Joseph Brodsky, Vladimir Nabokov, Karl Barth, and many others. He didn’t just translate from one language to another, he overcame the chronological distance and created a linguistic bridge between eras. Winner of the Maurice Waxmacher and Andrei Bely awards.

Literary critic is not only modern literature, sharp, clear, convincing. In the program “School of Scandal,” he, among other things, talks about Northerner and his lace, which never established itself in the cultural field, and tragically turned into self-parody.

And here important quote from a program text on how to read modern poetry:

“The correct reader of poetry is a paranoid one. This is a person who is constantly thinking about some important thing for him - like someone who is in prison and is thinking about escaping. He looks at everything from this point of view: this thing can be a tool for digging, this window can be climbed out, this guard can be bribed. And if he goes there as an inspector, he will see something else, say, a violation of order, and if as an idle tourist, he will see only what differs from his previous ideas, or what is shown to him. A reader who does not perceive what seems to us to be the treasures of poetry is simply a person without his own, paranoid and almost aggressive thought about something personally most important to him - like, say, the thought about the fate of the state for the reader of Horace or the thought about his Self for the reader of romantic poetry. The stronger this thought is in a person, the more he is ready to see the answer to it in texts that are far from him, it is unclear what they are talking about or seem to be talking about something completely wrong. We are all familiar with this from critical moments in life: when we are waiting for an answer to a vital question from a doctor or from a loved one, we see signs in everything: yes or no. The more intensely we think about it, the more clues we see, and for an indifferent person the answer will only be a letter from the doctor himself. So, modern poetry is designed for people with a lot of different burning questions that were not agreed upon in advance between the author and the reader.”

**About Grigory Dashevsky

Mikhail Aizenberg, poet:**

This was one of the the best people that I have seen in my life. And one of the most smart people in the country. This combination seems unrealistic, but it is true. We who knew him were incredibly lucky. The more terrible the loss.

From his personal selection of Dashevsky's poems, Eisenberg cited three:

Neither yourself nor people

no here, doesn't happen.

The commandment illuminates

snot, burdock, mosquito.

A faint singing whines,

invisible saw:

as if a villain is sawing,

and the innocent suffer

turning white.

But the law is without people

shines in the desert:

there is no evil or patience here,

no face - just flickering

mosquito wing.

NESCUCHNY GARDEN (3)

1

We'll go out into the air

we'll talk there.

Air, you are invisible,

like someone else's heart,

and faithful to the grave.

At least you

you'll be glad to warm up

in my voice.

2

You in early spring

in the emptiness of spring,

how is it, wounded

needles of dawn

or bare branches

and moving

several shadows

from rare passersby,

for example, mine.

3

Who is cruel, who is pathetic,

number of someone's shadow -

conscience, someone's - passion.

Willy-nilly,

remorse, sting

if the shadow pierces

heart is an impression,

that she's just

part, his own part.

4

Cloudy in the bedrooms

only kitchen frames

we were enlightened at once

in our inhabited

stone advertising

happiness or evil.

My life was kept

not in mine, but in the distance

heart like a needle.

5

And about the one who cries,

saying for so long:

intercede, have mercy,

I said that means:

at least my needle

blunt it, break it.

But not you, transparent one,

and neona lived,

blink letters.

AT THE METRO

- Look if it flashed Yes

in the always late eyes?

- No, there’s a brown sunset, sometimes

light brown fear.

- Let her silent tears pass,

phrases, pauses, wait,

like not those who rose there,

missed, skip.

- But it hasn’t sounded yet

and until I met him,

from the wrong ones, from silence, from tears

can I tell the difference?

- That’s why don’t take her away,

as if from a staircase, piercing eyes:

won't it sparkle in the middle?

pouring in from below?

- You seem to mean

that the oath swears to come

in the heart of the one who promised I'll come

about nine.

- For me and for the lingering vows

there is no sweeter heart:

so a more diligent, more pitiful look:

I'll see her with them.

- But having gotten used to forever, To forever,

They don’t even mind wasting their lives:

nice - not nice, what is a person for them,

sighs or sadness?

- Waiting and living is just an excuse

to challenge someone unknown,

so that you can stay with her

the eyes of their immortal ones.

September 1990

***

Victor Sonkin, translator and journalist:

I searched for a long time and could not find a fragment from an online discussion where someone - it seemed to me that Sergei Kuznetsov - was having a regular conversation about the Russian nineties, with the usual poles (from “the era of freedom” to “the era of shame”). I almost never could get hold of anything in such discussions, because every now and then, as if it were everyday life, they started talking about things that I, who lived in Russia in the nineties, not only had never seen, but also had no idea about their existence. And in this discussion Grisha Dashevsky appeared and said that it was a time of such fragmentation of society and public consciousness, that there cannot be a single picture - everyone has their own nineties.

This amazing, transcendental look without arrogance, a look that could shame those arguing and teach real, not ostentatious, but intellectual humility - that quality that we are terribly lacking, and now, without Dashevsky, will be missed even more.

My favorite poem of his is “Mana is not zero”; I don’t quote it, it’s long, but it’s easy to search for. This is a translation from Propertius, precisely a translation, but not only from Latin into Russian, but also from the 1st century BC. e. into the 21st century. There were many such attempts, but only a few successful ones.

And he was perhaps the only critic of translation in our literary environment - a person who was interested in this problem not on a superficial level, but conceptually, and who at the same time knew how to tell the reader about it.

Here is a recording of Grigory Dashevsky’s meeting with students of our translation seminar. Basically - an analysis of one poem by Catullus.

Kirill Ospovat, philologist:

Grigory Dashevsky was my university teacher, Grigory Mikhailovich, he once read Horace with us. His non-academic talk about the most different texts also sounded like a characteristic combination of friendliness towards those not entirely initiated with full responsibility for accumulated knowledge and developed thought - a combination thanks to which the most demanding science has been reproduced since the time of Socrates. Sometimes the almost physically felt genius of his speech, like the strength of an athlete, was the effect of the visual execution of a thought in a movement that was at once skillfully purposeful and fleetingly unpredictable. There is no language to talk about his illness, but against its background he seemed to be an example of the sovereignty of mind and will.

Oleg Lekmanov, philologist:

Grisha Dashevsky was one of the best people I knew. Placed by external circumstances in very, very difficult conditions, he never complained, but he never pretended that his life was easy. He joked, drank, read carefully, mocked, was indignant, admired, was indignant again, and it was impossible not to admire him, his beautiful face, shimmering like the best portraits of Van der Weyden. One could disagree with Grisha’s critical assessments, but one could not ignore them. But he was also a wonderful poet, translator, expert on antiquity, and teacher. It’s hard to write, tears are blurring my eyes, what a terrible word “was.” Forgive us, Grisha!

Sasha Finogenova, student of the Russian State University for the Humanities, 1992-1997.

translator, editor:

Dashevsky...

Those who, like me, recognized Grigory Mikhailovich, Grisha, at the very beginning of their adult life - at about 18 years old - will never forget this feeling of light and a huge world suddenly opening up, arising from one of his exact words. And sometimes even a glance. He is very special, this look, look at any photo.

He taught us, history students of the Russian State University for the Humanities, Latin in 1992-1997. Since then, our communication has not stopped, only the degree has changed a little. To a friendly one. And this Latin of his, Dashevsky, revealed to us a dazzling and so airy, clear ancient poetry, not at all similar to the frozen, multi-toned marble lines of translations of the 19th century. He brought to life all the words and concepts to which he turned his attention, that's it.

I think his influence on people precisely as a teacher-friend, and not only on his students, but on everyone who found himself in his orbit, is immeasurable. His thoughtful questions about your doubts or experiences, as well as his surprisingly consistent interest in your first texts, works, poems - each has its own - can only be explained by this unique gift, to discern and love a person, simply. I can’t remember him talking to anyone formally, without “turning on.” This is immediately noticeable in any of his texts, critical or artistic. The absence of cliches, the aversion to them, is such a rare, priceless trait of Grishcha.

His advice and thoughts about people, first of all - in literature, politics, love, friendship, religion - live in us, his friends and colleagues, they constantly pulsate, haunt us, encourage us to new thoughts and actions.

No, I can’t believe he’s leaving at all.

...And we never switched to “you.”

- In contact with 0

- Google+ 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0