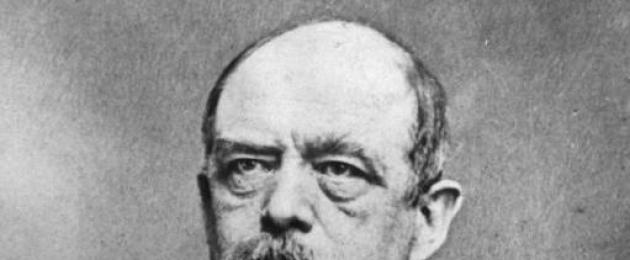

Otto Bismarck is one of the most famous politicians of the 19th century. He had a significant influence on political life in Europe and developed a security system. Played a key role in uniting the German peoples into a single national state. He was awarded many awards and titles. Subsequently, historians and politicians will have different assessments of who created

The biography of the chancellor is still between representatives of various political movements. In this article we will take a closer look at it.

Otto von Bismarck: short biography. Childhood

Otto was born on April 1, 1815 in Pomerania. Representatives of his family were cadets. These are the descendants of medieval knights who received lands for serving the king. The Bismarcks had a small estate and held various military and civilian posts in the Prussian nomenklatura. By the standards of 19th-century German nobility, the family had rather modest resources.

Young Otto was sent to the Plaman school, where students were hardened by hard physical exercises. The mother was an ardent Catholic and wanted her son to be raised in strict conservatism. By the time he was a teenager, Otto transferred to a gymnasium. There he did not establish himself as a diligent student. I couldn’t boast of any success in my studies either. But at the same time I read a lot and was interested in politics and history. He studied the features of the political structure of Russia and France. I even learned French. At the age of 15, Bismarck decides to associate himself with politics. But the mother, who was the head of the family, insists on studying in Göttingen. Law and jurisprudence were chosen as the direction. Young Otto was to become a Prussian diplomat.

Bismarck's behavior in Hanover, where he trained, is legendary. He did not want to study law, so he preferred a wild life to studying. Like all elite youth, he often visited entertainment venues and made many friends among the nobles. It was at this time that the hot temper of the future chancellor manifested itself. He often gets into skirmishes and disputes, which he prefers to resolve with a duel. According to the recollections of university friends, in just a few years of his stay in Göttingen, Otto participated in 27 duels. As a lifelong memory of his stormy youth, he had a scar on his cheek after one of these competitions.

Leaving the university

A luxurious life alongside the children of aristocrats and politicians was beyond the means of Bismarck's relatively modest family. And constant participation in troubles caused problems with the law and the management of the university. So, without receiving a diploma, Otto went to Berlin, where he entered another university. Which he graduated a year later. After this, he decided to follow his mother’s advice and become a diplomat. Each figure at that time was personally approved by the Minister of Foreign Affairs. After studying Bismarck's case and learning about his problems with the law in Hanover, he refused to give the young graduate a job.

After the collapse of his hopes of becoming a diplomat, Otto works in Anhen, where he deals with minor organizational issues. According to the recollections of Bismarck himself, the work did not require significant effort from him, and he could devote himself to self-development and relaxation. But even in his new place, the future chancellor has problems with the law, so after a few years he enlists in the army. His military career did not last long. A year later, Bismarck's mother dies, and he is forced to return to Pomerania, where their family estate is located.

In Pomerania, Otto faces a number of difficulties. This is a real test for him. Managing a large estate requires a lot of effort. So Bismarck has to give up his student habits. Thanks to his successful work, he significantly raises the status of the estate and increases his income. From a serene youth he turns into a respected cadet. Nevertheless, the hot temper continues to remind itself. The neighbors called Otto "mad."

A few years later, Bismarck's sister Malvina arrives from Berlin. He becomes very close to her due to their common interests and outlook on life. Around the same time, he became an ardent Lutheran and read the Bible every day. The future chancellor's engagement to Johanna Puttkamer takes place.

The beginning of the political path

In the 40s of the 19th century, a fierce struggle for power began in Prussia between liberals and conservatives. To relieve tension, Kaiser Friedrich Wilhelm convenes the Landtag. Elections are being held in local administrations. Otto decides to go into politics and without much effort becomes a deputy. From his first days in the Landtag, Bismarck gained fame. Newspapers write about him as a “mad cadet from Pomerania.” He speaks quite harshly about liberals. Compiles entire articles of devastating criticism of Georg Finke.

His speeches are quite expressive and inspiring, so Bismarck quickly becomes a significant figure in the camp of conservatives.

Confrontation with liberals

At this time, a serious crisis is brewing in the country. A series of revolutions are taking place in neighboring states. Inspired by it, liberals are conducting active propaganda among the working and poor German population. Strikes and walkouts occur repeatedly. Against this background, food prices are constantly rising and unemployment is growing. As a result, the social crisis leads to revolution. It was organized by patriots together with liberals, demanding that the king adopt a new Constitution and unite all German lands into one national state. Bismarck was very frightened of this revolution; he sent the king a letter asking him to entrust him with the army’s march on Berlin. But Frederick makes concessions and partially agrees with the demands of the rebels. As a result, bloodshed was avoided, and the reforms were not as radical as in France or Austria.

In response to the victory of the liberals, a camarilla is created - an organization of conservative reactionaries. Bismarck immediately joins it and conducts active propaganda through. By agreement with the king, a military coup takes place in 1848, and the right regains its lost positions. But Frederick is in no hurry to empower his new allies, and Bismarck is actually removed from power.

Conflict with Austria

At this time, the German lands were greatly fragmented into large and small principalities, which in one way or another depended on Austria and Prussia. These two states waged a constant struggle for the right to be considered the unifying center of the German nation. By the end of the 40s, there was a serious conflict over the Principality of Erfurt. Relations deteriorated sharply, and rumors began to spread about possible mobilization. Bismarck takes an active part in resolving the conflict, and he manages to insist on signing agreements with Austria in Olmütz, since, in his opinion, Prussia was not able to resolve the conflict militarily.

Bismarck believes that it is necessary to begin long-term preparations for the destruction of Austrian dominance in the so-called German space.

To do this, according to Otto, it is necessary to conclude an alliance with France and Russia. Therefore, with the beginning of the Crimean War, he actively campaigned not to enter into the conflict on the side of Austria. His efforts bear fruit: there is no mobilization, and the German states remain neutral. The king sees promise in the plans of the “mad cadet” and sends him as ambassador to France. After negotiations with Napoleon III, Bismarck was suddenly recalled from Paris and sent to Russia.

Otto in Russia

Contemporaries say that the formation of the Iron Chancellor’s personality was greatly influenced by his stay in Russia; Otto Bismarck himself wrote about this. The biography of any diplomat includes a period of learning the skill. This is what Otto devoted himself to in St. Petersburg. In the capital, he spends a lot of time with Gorchakov, who was considered one of the most outstanding diplomats of his time. Bismarck was impressed by the Russian state and traditions. He liked the policies pursued by the emperor, so he carefully studied Russian history. I even started learning Russian. After a few years I could already speak it fluently. “Language gives me the opportunity to understand the very way of thinking and logic of the Russians,” wrote Otto von Bismarck. The biography of the “mad” student and cadet brought disrepute to the diplomat and interfered with successful activities in many countries, but not in Russia. This is another reason why Otto liked our country.

In it he saw an example for the development of the German state, since the Russians managed to unite lands with an ethnically identical population, which was a long-standing dream of the Germans. In addition to diplomatic contacts, Bismarck makes many personal connections.

But Bismarck’s quotes about Russia cannot be called flattering: “Never trust the Russians, for the Russians do not even trust themselves”; “Russia is dangerous because of the meagerness of its needs.”

Prime Minister

Gorchakov taught Otto the basics of an aggressive foreign policy, which was very necessary for Prussia. After the king's death, the "mad cadet" is sent to Paris as a diplomat. He faces the serious task of preventing the restoration of the long-standing alliance between France and England. The new government in Paris, created after the next revolution, had a negative attitude towards the ardent conservative from Prussia.

But Bismarck managed to convince the French of the need for mutual cooperation with the Russian Empire and the German lands. The ambassador selected only trusted people for his team. Assistants selected candidates, then Otto Bismarck himself examined them. A short biography of the applicants was compiled by the king's secret police.

Successful work in establishing international relations allowed Bismarck to become Prime Minister of Prussia. In this position, he won the true love of the people. Otto von Bismarck graced the front pages of German newspapers every week. The politician's quotes became popular far abroad. Such fame in the press is due to the Prime Minister’s love of populist statements. For example, the words: “The great questions of the time are decided not by speeches and resolutions of the majority, but by iron and blood!” are still used on a par with similar statements by the rulers of Ancient Rome. One of the most famous sayings of Otto von Bismarck: “Stupidity is a gift of God, but it should not be abused.”

Prussian territorial expansion

Prussia has long set itself the goal of uniting all German lands into one state. For this purpose, preparations were made not only in the foreign policy aspect, but also in the field of propaganda. The main rival for leadership and patronage of the German world was Austria. In 1866, relations with Denmark sharply worsened. Part of the kingdom was occupied by ethnic Germans. Under pressure from the nationalist-minded part of the public, they began to demand the right to self-determination. At this time, Chancellor Otto Bismarck secured the full support of the king and received expanded rights. The war with Denmark began. Prussian troops occupied the territory of Holstein without any problems and divided it with Austria.

Because of these lands, a new conflict arose with the neighbor. The Habsburgs, who were seated in Austria, were losing their position in Europe after a series of revolutions and coups that overthrew representatives of the dynasty in other countries. In the 2 years after the Danish War, hostility between Austria and Prussia grew in the first trade blockades and political pressure. But very soon it became clear that it would not be possible to avoid a direct military conflict. Both countries began to mobilize their populations. Otto von Bismarck played a key role in the conflict. Having briefly outlined his goals to the king, he immediately went to Italy to enlist her support. The Italians themselves also had claims to Austria, seeking to take possession of Venice. In 1866 the war began. Prussian troops managed to quickly capture part of the territories and force the Habsburgs to sign a peace treaty on terms favorable to themselves.

Land unification

Now all the ways for the unification of the German lands were open. Prussia set a course for creating a constitution for which Otto von Bismarck himself wrote. The Chancellor's quotes about the unity of the German people gained popularity in northern France. The growing influence of Prussia greatly worried the French. The Russian Empire also began to wait warily to see what Otto von Bismarck, whose short biography is described in the article, would do. The history of Russian-Prussian relations during the reign of the Iron Chancellor is very revealing. The politician managed to assure Alexander II of his intentions to cooperate with the Empire in the future.

But the French could not be convinced of this. As a result, another war began. A few years earlier, an army reform was carried out in Prussia, as a result of which a regular army was created.

Military spending also increased. Thanks to this and the successful actions of German generals, France suffered a number of major defeats. Napoleon III was captured. Paris was forced to agree, losing a number of territories.

On a wave of triumph, the Second Reich is proclaimed, Wilhelm becomes emperor, and Otto Bismarck becomes his confidant. Quotes from Roman generals at the coronation gave the chancellor another nickname - “triumphant”; since then he was often depicted on a Roman chariot and with a wreath on his head.

Heritage

Constant wars and internal political squabbles seriously undermined the politician’s health. He went on vacation several times, but was forced to return due to a new crisis. Even after 65 years, he continued to take an active part in all political processes in the country. Not a single meeting of the Landtag took place unless Otto von Bismarck was present. Interesting facts about the life of the chancellor are described below.

For 40 years in politics, he achieved enormous success. Prussia expanded its territories and was able to gain superiority in German space. Contacts were established with the Russian Empire and France. All these achievements would not have been possible without a figure like Otto Bismarck. The photo of the chancellor in profile and wearing a combat helmet became a kind of symbol of his unyieldingly tough foreign and domestic policy.

Disputes surrounding this personality are still ongoing. But in Germany, every person knows who Otto von Bismarck was - the iron chancellor. There is no consensus on why he was called that. Either because of his hot temper, or because of his ruthlessness towards his enemies. One way or another, he had a huge influence on world politics.

- Bismarck began his mornings with physical exercise and prayer.

- While in Russia, Otto learned to speak Russian.

- In St. Petersburg, Bismarck was invited to participate in the royal fun. This is bear hunting in the forests. The German even managed to kill several animals. But during the next sortie, the detachment got lost, and the diplomat received serious frostbite on his legs. Doctors predicted amputation, but everything worked out.

- In his youth, Bismarck was an avid duelist. He took part in 27 duels and received a scar on his face in one of them.

- Otto von Bismarck was once asked how he chose his profession. He replied: “I was destined by nature to become a diplomat: I was born on the first of April.”

As a result of the defeat of the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, the French Emperor Napoleon III was captured, and Paris had to go through another revolution. And on March 2, 1871, the difficult and humiliating Treaty of Paris was concluded for France. The territories of Alsace and Lorraine, the kingdoms of Saxony, Bavaria and Württemberg were annexed to Prussia. France should have paid 5 billion indemnities to the winners. Wilhelm I returned to Berlin in triumph, despite the fact that all the credit for this war belonged to the chancellor.

Victory in this war made possible the revival of the German Empire. Back in November 1870, the unification of the southern German states took place within the framework of the United German Confederation, transformed from the Northern one. And in December 1870, the Bavarian king made a proposal to restore the German Empire and German imperial dignity, which were once destroyed by Napoleon Bonaparte. This proposal was accepted, and the Reichstag sent a request to Wilhelm I to accept the imperial crown. On January 18, 1871, Otto von Bismarck (1815 - 1898) proclaimed the creation of the Second Reich, and Wilhelm I was proclaimed Emperor (Kaiser) of Germany. At Versailles in 1871, when writing the address on the envelope, Wilhelm I indicated "Chancellor of the German Empire", thus confirming Bismarck's right to rule the created empire.

The “Iron Chancellor,” acting in the interests of absolute power, ruled the newly formed state in 1871-1890, from 1866 to 1878, with the support of the National Liberal Party in the Reichstag. Bismarck carried out global reforms in the field of German law, and he also did not ignore the system of management and finance. The implementation of educational reform in 1873 gave rise to a conflict with the Roman Catholic Church, although the main reason for the conflict was the growing distrust of German Catholics (who made up almost a third of all the country's inhabitants) towards the Protestant population of Prussia. In the early 1870s, after these contradictions manifested themselves in the work of the Catholic Center Party in the Reichstag, Bismarck was forced to take action. The fight against the dominance of the Catholic Church is known as the Kulturkampf (struggle for culture). During this struggle, many bishops and priests were placed under arrest, and hundreds of dioceses were left without leaders. Subsequently, church appointments had to be coordinated with the state; Church officials were not allowed to hold official positions in the state apparatus. Schools were separated from the church, the institution of civil marriage was created, and the Jesuits were completely expelled from Germany.

In constructing his foreign policy, Bismarck was based on the situation that arose in 1871 thanks to the victory of Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War and the acquisition of Alsace and Lorraine, which turned into a source of continuous tension. Using a complex system of alliances that made it possible to ensure the isolation of France, the rapprochement of the German state with Austria-Hungary, as well as maintaining good relations with the Russian Empire (the alliance of three emperors: Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1873 and 1881; the existence of the Austro-German alliance in 1879 year; the conclusion of the “Triple Alliance” between the rulers of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy in 1882; the “Mediterranean Agreement” of Austria-Hungary, Italy and England in 1887, as well as the conclusion of the “reinsurance treaty” with Russia in 1887), Bismarck supported peace throughout Europe. During the reign of Chancellor Bismarck, the German Empire became one of the leaders in the international political arena.

When building his foreign policy, Bismarck made a lot of efforts to consolidate the gains gained as a result of the signing of the Frankfurt Peace in 1871, sought to ensure the diplomatic isolation of the French Republic and tried by any means to prevent the formation of any coalition if it could become a threat to German hegemony. He preferred not to take part in discussions of claims against the weakened Ottoman Empire. Despite the fact that the “Triple Alliance” was concluded against France and Russia, the “Iron Chancellor” was firmly convinced that a war with Russia could be extremely dangerous for Germany. The existence of a secret treaty with Russia in 1887 - a “reinsurance treaty” - shows that Bismarck was not above acting behind the backs of his own allies, Italy and Austria, in order to maintain the status quo both in the Balkans and in the Middle East.

When building his foreign policy, Bismarck made a lot of efforts to consolidate the gains gained as a result of the signing of the Frankfurt Peace in 1871, sought to ensure the diplomatic isolation of the French Republic and tried by any means to prevent the formation of any coalition if it could become a threat to German hegemony. He preferred not to take part in discussions of claims against the weakened Ottoman Empire. Despite the fact that the “Triple Alliance” was concluded against France and Russia, the “Iron Chancellor” was firmly convinced that a war with Russia could be extremely dangerous for Germany. The existence of a secret treaty with Russia in 1887 - a “reinsurance treaty” - shows that Bismarck was not above acting behind the backs of his own allies, Italy and Austria, in order to maintain the status quo both in the Balkans and in the Middle East.

And Bismarck did not clearly define the course of colonial policy until 1884; the main reason for this was friendly relations with England. Among other reasons, it is customary to cite the desire to preserve public capital by minimizing government expenses. The first expansionist plans of the “Iron Chancellor” were met with energetic protest from every party - Catholics, socialists, statists, as well as among the junkers who represented him. Despite this, it was during the reign of Bismarck that Germany became a colonial empire.

In 1879, Bismarck broke with the liberals, subsequently relying only on the support of a coalition of large landowners, the military and state elite, and industrialists.

At the same time, Chancellor Bismarck managed to get the Reichstag to adopt a protective customs tariff. Liberals were forced out of big politics. The direction of the new course of economic and financial policy of the German Empire reflected the interests of large industrialists and farmers. This union managed to occupy a dominant position in the sphere of public administration and political life. Thus, there was a gradual transition of Otto von Bismarck from the Kulturkampf policy to the beginning of the persecution of socialists. After the attempt on the life of the sovereign in 1878, Bismarck passed through the Reichstag an “exceptional law” directed against the socialists, since it prohibited the activities of any social democratic organization. The constructive side of this law was the introduction of a state insurance system in case of illness (1883) or injury (1884), as well as old-age pensions (1889). But even these measures were not enough to alienate the German workers from the Social Democratic Party, although it distracted them from revolutionary ways of solving social problems. However, Bismarck strongly opposed any version of legislation that would regulate the working conditions of workers.

During the reign of Wilhelm I and Frederick III, who ruled for no more than six months, not a single opposition group managed to shake Bismarck's position. The self-confident and ambitious Kaiser was disgusted by the secondary role, and at the next banquet in 1891 he declared: “There is only one master in the country - I, and I will not tolerate another.” Shortly before this, Wilhelm II made a hint about the desirability of Bismarck's resignation, whose application was submitted on March 18, 1890. A couple of days later, the resignation was accepted, Bismarck was granted the title of Duke of Lauenburg and awarded the rank of Colonel General of the Cavalry.

Having retired to Friedrichsruhe, Bismarck did not lose interest in political life. The newly appointed Reich Chancellor and Minister-President, Count Leo von Caprivi, was especially eloquently criticized by him. In Berlin in 1894, a meeting took place between the emperor and the already aging Bismarck, organized by Clovis Hohenlohe, Prince of Schillingfürst, Caprivi's successor. The entire German people took part in the celebration of the 80th anniversary of the “Iron Chancellor” in 1895. In 1896, Prince Otto von Bismarck had the opportunity to attend the coronation of Russian Emperor Nicholas II. Death overtook the “Iron Chancellor” on July 30, 1898 at his Friedrichsruhe estate, where he was buried.

Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck (1815–1898) came from Pomeranian Junkers, a noble family whose founder was a foreman of a patrician merchant guild. The Bismarcks were monarchists, but independent and even obstinate. Otto studied law at the universities of Göttingen and Berlin. During his student years, in three semesters, he managed to have twenty-seven duels and acquired several scars. Served in the army as a volunteer. I did housework and read a lot. Bismarck was a deputy of the Prussian Diet, a member of the Chamber of Deputies, Prussian envoy to the German Diet, ambassador to Russia and France. In 1862, he headed the Prussian government and began to solve pressing problems using “true Prussian” methods, “iron and blood.” Bismarck was considered a clever and flexible politician.

“A hero in appearance, always cheerful and tireless, resourceful and frankly unceremonious, imbued with a sense of personal independence, free from prejudices, conventional formulas and templates, with a flexible and courageous mind, with an extraordinary memory, with a remarkable ability to grasp the essence of each phenomenon or issue and determine with his apt word or image, he turned out to be created for a creative historical role.” After the accession of Wilhelm II, Bismarck, who did not want to put up with the limitation of his powers, resigned in 1890. For the last eight years he has lived on his estate.

Bismarck, like many other outstanding statesmen, is known for his statements, many of which became popular and turned into aphorisms. “The great questions of the time are decided not by speeches or decisions of the majority, but by iron and blood,” he said in his famous speech in the Landtag in 1862. Bismarck became Minister-President (Prime Minister) of Prussia and set about fulfilling the main task that had arisen in German society. It was he who “with iron and blood” completed the unification of the German lands around Prussia into a single state - Germany.

Everything was done in a fairly short period of time. First, Bismarck completed military reform and strengthened the German army. In 1864, Denmark was quickly defeated, from which, with the support of Austria, the southern regions of Schleswig and Holstein were taken away. In 1866, Austria was defeated in a short war. She recognized Prussia's right to create the North German Confederation, which united twenty-one German states. Then there was a victory over France. On January 18, 1871, the Prussian king was proclaimed Emperor of the German Reich. This was the so-called Second Reich. The First Reich was considered the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation, and the Third Reich in the 30s. XX century was proclaimed Hitler. Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck became the first Chancellor of the German Empire and went down in the history of this country as one of its most prominent figures.

However, it would be wrong to talk about the exclusively “anti-people”, “reactionary” nature of Bismarck’s policies. He enjoyed enormous authority, was a recognized leader - the Iron Chancellor, and the German lands quickly rallied, forming a strong national unity. The country was on the rise.

This was facilitated by fairly decisive reforms, the German revolution from above. In the first half of the 70s. XIX century a single gold currency replaced numerous banknotes of individual kingdoms and principalities. A unified postal system emerged and an imperial bank was formed. A uniform set of criminal laws for the entire country came into force. Administrative reform limited the local power of the Junkers, but Prussian-German spirit of militarism spread throughout the country. The peacetime army grew to 400 thousand people. According to the law on the septennate, military expenditures were approved by the Reichstag for seven years in advance.

Agriculture developed according to the so-called the Prussian way. Large Junker (landowner) landownership remained, the position of German wealthy peasants (grossbauers, “large peasants,” or kulaks in the Russian version) strengthened, but two-thirds of all farms by the end of the century remained dwarf (less than 2 hectares). Landless and land-poor peasants were dependent on large landowners.

Over the next twenty years, fundamental changes occurred in the economic and political life of the country. The Industrial Revolution was over, and industrialization was unfolding using the most advanced technology. played a big role indemnity 5 billion francs, which had to be paid to defeated France, as well as the development of the iron ore reserves of Alsace and Lorraine, taken from this country. Over the past twenty years, steel production in Germany has increased eleven times, potassium salt production four times, and coal production two and a half times. By the beginning of the 90s. XIX century Over 50% of the population was employed in industry, transport and trade.

In Germany, as in the USA, on the basis of the concentration of production and financial capital, there was monopolization of production in metallurgy, coal, chemical and electrical industries. By the end of the century, the financial sector was dominated by six major banks. Businessmen such as Kirdorff, Krupp, Stupp, Hansemann and others gained increasing influence on the government's domestic and foreign policy. High duties were introduced on imported goods, which saved monopolists from competition.

German product manufacturers themselves widely used dumping, that is, they sold goods abroad at bargain prices and conquered new markets.

The interests of the industrial bourgeoisie and the Junkers were defended by the German state. According to the constitution of 1871, the German emperor could only be Prussian king. He approved and rejected bills, convened and dissolved Reichstag- Imperial Parliament, led the armed forces. Responsible to the emperor imperial chancellor(Minister-President of Prussia), who was the only all-German minister.

The Reichstag was elected on the basis universal suffrage for men over the age of twenty-five. Women, military personnel and men under this age did not have the right to vote. The Reichstag dealt with legislation and budget approval. His rights were limited by the actions of the upper house - the Union Council, as well as the enormous powers of the emperor, to whom the government was subordinate.

In Soviet times, it was not customary to say that it was Bismarck who took the first steps towards creating social state. On the one hand, he banned the activities of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which was rapidly increasing its influence on the working masses. At the same time, important laws were adopted that regulated the sphere of social relations. “The cornerstone of the concept of the welfare state was laid by Bismarck in 1883... Bismarck's extensive reforms marked a turn in the development of public policy and the assumption of responsibility in this area... In 1871, Bismarck passed a law obliging employers to pay financial compensation for industrial accidents ... Bismarck considered every social problem from the point of view of the interests and security of the state. He was against private sector participation in social insurance because such participation, in his opinion, could bring with it motives of material abuse and profiteering (more like economic speculation as opposed to his own political speculations). Moreover, it could make workers loyal to the enterprise in which they work rather than to the state. The Chancellor believed that workers should therefore turn to the state for help,” a lot of interesting things can be learned from a modest book by a Norwegian author, which is practically unknown even among Russian readers.

The fact remains that Bismarck managed to start a big game on the opponent’s field. There is reason to believe that Bismarck was one of those who began to build “capitalism with a human face.” Over the next hundred and fifty years, much has been done in this direction. And in the USSR, for some reason, socialism ended precisely when the first calls were made to create “socialism with a human face.”

The Prussian government eventually obtained from parliament the opportunity to implement the policy of its prime minister, Bismarck, aimed at ensuring Prussian hegemony in German affairs. This was also facilitated by the circumstances that arose in the international arena in the early 60s.

It was precisely at this time that a cooling began between France and Russia, since the French government, contrary to its obligations, did not raise the issue of revising the articles of the Treaty of Paris of 1856, which were unfavorable and humiliating for Russia after the defeat in the Crimean War. At the same time, due to the struggle for colonies, deterioration of relations between Russia, Great Britain and France. Mutual contradictions diverted the attention of the largest European powers from Prussia, which created a favorable environment for the implementation of the policy of Prussian Junkerism.

Given the great international influence in the Russian region, Bismarck set as his goal the improvement of Prussian-Russian relations. During the Polish uprising in 1863, he proposed to Alexander II a draft agreement on the joint struggle of Russia and Prussia against the Polish rebels. Such an agreement was concluded in February 1863 (the so-called Alvensleben Convention). Although it remained unratified and was not implemented in practice, its signing contributed to the improvement of relations between Prussia and Russia. At the same time, the contradictions between Great Britain and France, on the one hand, and Russia, on the other, became heated. In addition, the first, in connection with the American Civil War, were busy with American affairs.

Bismarck took advantage of these contradictions among the European powers, primarily to tear away Schleswig and Holstein, which belonged to Denmark, from Denmark. These two provinces, located at the junction between the Baltic and North Seas, have long attracted the German military and the bourgeoisie with their advantageous economic and strategic position. A significant part of the population of these provinces was of German origin and gravitated toward Germany, which Bismarck also exploited.

In November 1863, the Danish king Frederick VII died and his heir Christian IX ascended the throne. Bismarck decided to use this moment to attack Denmark. Taking advantage of the good disposition of the Russian Emperor (an important circumstance was the fact that Tsar Alexander II was the nephew of the Prussian King William 1) and having agreed with the Emperor of Austria Franz Joseph, the Prime Minister of Prussia began to look for a reason to declare war.

The reason was the new Danish constitution, which infringed on the rights of Schleswig. In January 1864, Prussian troops, together with Austrian troops, attacked Denmark. The war lasted 4 months: such a small and weak country as Denmark, from which both Great Britain and France turned their backs at that moment, was unable to resist two strong opponents. By the peace treaty Denmark was forced to give up Schleswig and Holstein; Schleswig with the seaport of Kiel came under the control of Prussia, Holstein - Austria. Denmark retained the small territory of Lauenburg, which a year later for 2.5 million thalers in gold became the final possession of Prussia, which played an important role in subsequent events.

Having successfully completed the war with Denmark, Prussia immediately began to prepare for war against its recent ally, Austria, in order to weaken it and thus eliminate its influence in Germany. The Prussian General Staff, under the leadership of General Helmuth Karl von Moltke, and the War Ministry, headed by General von Rosn, were actively developing plans for the decisive battle.

At the same time, Bismarck waged an active diplomatic war against Austria, aimed at provoking a conflict with it and at the same time ensuring the neutrality of the great powers - Russia, France and Great Britain. Prussian diplomacy achieved success in this. The neutrality of Tsarist Russia in the war between Prussia and Austria turned out to be possible due to the deterioration of Austro-Russian relations; the tsar could not forgive Austria for its policies during the Crimean War of 1853 - 1856. Bismarck achieved the neutrality of Napoleon III with the help of vague promises of compensation in Europe (to which the Emperor of France still did not agree). Britain was caught up in a diplomatic struggle with France. Bismarck also managed to secure an alliance with Italy: the latter hoped to take Venice from Austria.

To ensure that the great powers (primarily France) did not have time to intervene in the conflict, Bismarck developed a plan for a lightning war with Austria. This plan was as follows: Prussian troops defeat the main forces of the enemy in one, maximum two battles, and, without putting forward any demands for the seizure of Austrian territories, they seek the main thing from the Austrian emperor - so that he refuses to interfere in German affairs and does not interfere with the transformation of the powerless German Empire. union into a new union of German states without Austria under Prussian hegemony.

As a pretext for war, Bismarck chose the issue of the situation in the Duchy of Holstein. Having found fault with the actions of the Austrian governor, Bismarck brought Prussian troops into the duchy. Austria, due to the remoteness of Holstein, could not transport its troops there and submitted a proposal to the all-German parliament, sitting in Frankfurt, to condemn Prussia for aggression. The Austrian proposal was also supported by a number of other German states: Bavaria, Saxony, Württemberg, Hanover, Baden. Bismarck's crude provocative policy set them against Prussia; the great-power plans of the Prussian military clique frightened them. The Prussian prime minister was accused of provoking a fratricidal war.

Despite everything, Bismarck continued to pursue his policy. June 17, 1866 war began. Prussian troops invaded the Czech lands of Austria. At the same time, Italy moved against Austria in the south. The Austrian command was forced to divide its forces. An army of 75 thousand was moved against the Italians, and 283 thousand people were deployed against the Prussians. The Prussian army numbered 254 thousand people, but was much better armed than the Austrian one; in particular, it had the most advanced needle gun for that time, loaded from the breech. Despite the significant numerical superiority and good weapons, the Italian army was defeated at the first meeting with the Austrians.

Bismarck found himself in a difficult position, because conflicts over the declaration of war had not been resolved between him, the Landtag and the king. Bismarck's position and the outcome of the entire war were saved by the talented strategist General Moltke, who commanded the Prussian army. On July 3, in the decisive battle of Sadovaya (near Königgrätz), the Austrians suffered a severe defeat and were forced to retreat.

In the circles of Prussian militarists, intoxicated by the victory, a plan arose to continue the war until the final defeat of Austria. They demanded that the Prussian army triumphantly enter Vienna, where Prussia would dictate peace terms to defeated Austria, providing for the separation of a number of territories from it. Bismarck strongly opposed this. He had serious reasons for this: two days after the Battle of Sadovaya, the government of Napoleon III, greatly alarmed by the unforeseen victories of Prussia, offered its peaceful mediation. Bismarck considered the danger of immediate armed intervention by France on the side of Austria, which could radically change the existing balance of forces; in addition, Bismarck's calculations did not include excessive weakening of Austria, since he intended to get closer to her in the future. Based on these considerations, Bismarck insisted on a speedy conclusion of peace.

On August 23, 1866, a peace treaty was signed between Prussia and Austria. Bismarck won another victory - Austria had to renounce its claims to a leading role in German affairs and withdraw from the German Confederation. Four German states that fought on the side of Austria - the kingdom of Hanover, the Electorate of Hesse-Kassel, the Duchy of Nassau and the city of Frankfurt am Main - were included in Prussia, and thus the stripes that separated the western and eastern possessions of the Prussian monarchy were eliminated. Austria also had to give Venice to Italy. New Italian attempts at Trieste and Triente failed.

5. North German Confederation

After new territorial conquests, Prussia became the largest German state with a population of 24 million people. Bismarck's government achieved the creation of the North German Confederation, which included 22 German states located north of the Main River. The Constitution of the North German Confederation, adopted in April 1867, legally consolidated Prussian hegemony in German territories. The Prussian king became the head of the North German Confederation. He had the supreme command of the armed forces of the union. In the Federal Council, which included representatives of the governments of all allied states, Prussia also occupied a dominant position.

Prussian Minister-President Bismarck became the Allied Chancellor. The Prussian General Staff actually became the highest military body of the entire North German Confederation. The all-Union parliament - the Reichstag - was to hold elections on the basis of universal (for men over 21 years of age) and direct (but not secret) voting, the majority of seats belonged to deputies from Prussia. However, the Reichstag enjoyed only minor political influence, since its decisions were not valid without the approval of the Federal Council, and, according to the law, the Bismarck government was not accountable to the Reichstag.

After the end of the Austro-Prussian War, Bavaria, Bürttemberg, Baden and Hesse-Darmstadt were forced to conclude agreements with Prussia to transfer the armed forces of these four southern German states under the control of the Prussian general staff.

Thus, Bismarck, having achieved the creation of the North German Confederation, in which the leadership indisputably belonged to Prussia, prepared Germany for a new war with France for the final completion of its unification.

The Franco-Prussian War was the result of the imperial policy of the moribund French Second Empire and the new aggressive state - Prussia, which wanted to assert its dominance in the center of Europe. The French ruling circles hoped, as a result of the war with Prussia, to prevent the unification of Germany, in which they saw a direct threat to the predominant position of France on the European continent, and, moreover, to seize the left bank of the Rhine, which had long been the object of desire of French capitalists. The French Emperor Napoleon III, in a victorious war, also sought a way out of a deep internal political crisis, which in the late 60s assumed a threatening character for his empire. The favorable outcome of the war, according to the calculations of Napoleon III, was supposed to strengthen the international position of the Second Empire, which had been greatly shaken in the 60s.

The Junkers and the major military industrialists of Prussia, for their part, sought war. They hoped, by defeating France, to weaken it, in particular, to capture the iron-rich and strategically important French provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. Bismarck, who already considered a war with France inevitable since 1866, was looking only for a favorable reason to enter into it: he wanted France, and not Prussia, to be the aggressive party that declared war. In this case, it would be possible to provoke a nationwide movement in the German states to accelerate the complete unification of Germany and thereby facilitate the transformation of the temporary North German Confederation into a more powerful centralized state - the German Empire under the leadership of Prussia.

At the age of 17, Bismarck entered the University of Göttingen, where he studied law. While a student, he gained a reputation as a reveler and brawler, and excelled in duels. In 1835 he received a diploma and was soon hired to work at the Berlin Municipal Court. In 1837 he took the position of tax official in Aachen, a year later - the same position in Potsdam. There he joined the Guards Jaeger Regiment. In the fall of 1838, Bismarck moved to Greifswald, where, in addition to performing his military duties, he studied animal breeding methods at the Elden Academy. His father's financial losses, together with an innate aversion to the lifestyle of a Prussian official, forced him to leave the service in 1839 and take over the leadership of the family estates in Pomerania. Bismarck continued his education, taking up the works of Hegel, Kant, Spinoza, D. Strauss and Feuerbach. In addition, he traveled in England and France. Later he joined the Pietists.

After his father's death in 1845, family property was divided and Bismarck received the estates of Schönhausen and Kniephof in Pomerania. In 1847 he married Johanna von Puttkamer. Among his new friends in Pomerania were Ernst Leopold von Gerlach and his brother, who were not only at the head of the Pomeranian Pietists, but also part of a group of court advisers. Bismarck, a student of the Gerlachs, became famous for his conservative stance during the constitutional struggle in Prussia in 1848–1850. Opposing the liberals, Bismarck contributed to the creation of various political organizations and newspapers, including the Neue Preussische Zeitung (New Prussian Newspaper). He was a member of the lower house of the Prussian parliament in 1849 and the Erfurt parliament in 1850, when he opposed the federation of the German states (with or without Austria), because he believed that this unification would strengthen the revolutionary movement that was gaining strength. In his Olmütz speech, Bismarck spoke in defense of King Frederick William IV, who capitulated to Austria and Russia. The pleased monarch wrote about Bismarck: “An ardent reactionary. Use later."

In May 1851, the king appointed Bismarck as Prussia's representative in the Union Diet in Frankfurt am Main. There, Bismarck almost immediately came to the conclusion that Prussia’s goal could not be a German confederation with Austria in a dominant position and that war with Austria was inevitable if Prussia took a dominant position in a united Germany. As Bismarck improved in the study of diplomacy and the art of statecraft, he increasingly moved away from the views of the king and his camarilla. For his part, the king began to lose confidence in Bismarck. In 1859, the king's brother Wilhelm, who was regent at that time, relieved Bismarck of his duties and sent him as envoy to St. Petersburg. There, Bismarck became close to the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Prince A.M. Gorchakov, who assisted Bismarck in his efforts aimed at diplomatic isolation of first Austria and then France.

Minister-President of Prussia.

In 1862, Bismarck was sent as envoy to France to the court of Napoleon III. He was soon recalled by King William I to resolve differences in the issue of military appropriations, which was heatedly discussed in the lower house of parliament. In September of the same year he became head of government, and a little later - minister-president and minister of foreign affairs of Prussia. A militant conservative, Bismarck announced to the liberal majority of parliament, consisting of representatives of the middle class, that the government would continue collecting taxes in accordance with the old budget, because parliament, due to internal contradictions, would not be able to pass a new budget. (This policy continued from 1863–1866, allowing Bismarck to carry out military reform.) At a parliamentary committee meeting on September 29, Bismarck emphasized: “The great questions of the time will not be decided by speeches and majority resolutions—that was the blunder of 1848 and 1949—but by iron.” and blood." Since the upper and lower houses of parliament were unable to develop a unified strategy on the issue of national defense, the government, according to Bismarck, should have taken the initiative and forced parliament to agree with its decisions. By limiting the activities of the press, Bismarck took serious measures to suppress the opposition.

For their part, the liberals sharply criticized Bismarck for proposing to support the Russian Emperor Alexander II in suppressing the Polish uprising of 1863–1864 (Alvensleben Convention of 1863). Over the next decade, Bismarck's policies led to three wars, which resulted in the unification of the German states into the North German Confederation in 1867: the war with Denmark (Danish War of 1864), Austria (Austro-Prussian War of 1866) and France (Franco-Prussian War of 1870). –1871). On April 9, 1866, the day after Bismarck signed a secret agreement on a military alliance with Italy in the event of an attack on Austria, he presented to the Bundestag his project for a German parliament and universal secret suffrage for the country's male population. After the decisive battle of Kötiggrätz (Sadowa), Bismarck managed to achieve the abandonment of the annexationist claims of Wilhelm I and the Prussian generals and offered Austria an honorable peace (Prague Peace of 1866). In Berlin, Bismarck introduced a bill to parliament exempting him from liability for unconstitutional actions, which was approved by the liberals. Over the next three years, Bismarck's secret diplomacy was directed against France. The publication in the press of the Ems Dispatch of 1870 (as revised by Bismarck) caused such indignation in France that on July 19, 1870, war was declared, which Bismarck actually won through diplomatic means even before it began.

Chancellor of the German Empire.

In 1871, at Versailles, Wilhelm I wrote on the envelope the address “to the Chancellor of the German Empire,” thereby confirming Bismarck’s right to rule the empire that he created and which was proclaimed on January 18 in the hall of mirrors at Versailles. The “Iron Chancellor,” representing the interests of the minority and absolute power, ruled this empire from 1871 to 1890, relying on the consent of the Reichstag, where from 1866 to 1878 he was supported by the National Liberal Party. Bismarck carried out reforms of German law, government and finance. The educational reforms he carried out in 1873 led to a conflict with the Roman Catholic Church, but the main reason for the conflict was the growing distrust of German Catholics (who made up about a third of the country's population) towards Protestant Prussia. When these contradictions manifested themselves in the activities of the Catholic Center Party in the Reichstag in the early 1870s, Bismarck was forced to take action. The struggle against the dominance of the Catholic Church was called the Kulturkampf (struggle for culture). During it, many bishops and priests were arrested, hundreds of dioceses were left without leaders. Church appointments now had to be coordinated with the state; clergy could not serve in the state apparatus.

In the field of foreign policy, Bismarck made every effort to consolidate the gains of the Frankfurt Peace of 1871, contributed to the diplomatic isolation of the French Republic and sought to prevent the formation of any coalition that threatened German hegemony. He chose not to participate in the discussion of claims against the weakened Ottoman Empire. When at the Berlin Congress of 1878, chaired by Bismarck, the next phase of the discussion of the “Eastern Question” ended, he played the role of an “honest broker” in the dispute between the rival parties. The secret treaty with Russia in 1887—the “reinsurance treaty”—showed Bismarck's ability to act behind the backs of his allies, Austria and Italy, to maintain the status quo in the Balkans and the Middle East.

Until 1884, Bismarck did not give clear definitions of the course of colonial policy, mainly due to friendly relations with England. Other reasons were the desire to preserve German capital and minimize government spending. Bismarck's first expansionist plans aroused vigorous protests from all parties - Catholics, statists, socialists and even representatives of his own class - the Junkers. Despite this, under Bismarck Germany began to transform into a colonial empire.

In 1879, Bismarck broke with the liberals and subsequently relied on a coalition of large landowners, industrialists, and senior military and government officials. He gradually moved from the Kulturkampf policy to the persecution of socialists. The constructive side of his negative prohibitive position was the introduction of a system of state insurance for sickness (1883), in case of injury (1884) and old-age pensions (1889). However, these measures could not isolate German workers from the Social Democratic Party, although they distracted them from revolutionary methods of solving social problems. At the same time, Bismarck opposed any legislation regulating the working conditions of workers.

Conflict with Wilhelm II.

With the accession of Wilhelm II in 1888, Bismarck lost control of the government. Under Wilhelm I and Frederick III, who ruled for less than six months, none of the opposition groups could shake Bismarck's position. The self-confident and ambitious Kaiser refused to play a secondary role, and his strained relationship with the Reich Chancellor became increasingly strained. The most serious differences appeared on the issue of amending the Exclusive Law against Socialists (in force in 1878–1890) and on the right of ministers subordinate to the Chancellor to a personal audience with the Emperor. Wilhelm II hinted to Bismarck about the desirability of his resignation and received a resignation letter from Bismarck on March 18, 1890. The resignation was accepted two days later, Bismarck received the title of Duke of Lauenburg, and he was also awarded the rank of Colonel General of the Cavalry.

Bismarck's removal to Friedrichsruhe was not the end of his interest in political life. He was especially eloquent in his criticism of the newly appointed Reich Chancellor and Minister-President Count Leo von Caprivi. In 1891, Bismarck was elected to the Reichstag from Hanover, but never took his seat there, and two years later he refused to stand for re-election. In 1894, the emperor and the already aging Bismarck met again in Berlin - at the suggestion of Clovis of Hohenlohe, Prince of Schillingfürst, Caprivi's successor. In 1895, all of Germany celebrated the 80th anniversary of the “Iron Chancellor”. Bismarck died in Friedrichsruhe on July 30, 1898.

Bismarck's literary monument is his Thoughts and memories (Gedanken und Erinnerungen), A Big politics of European cabinets (Die grosse Politik der europaischen Kabinette, 1871–1914, 1924–1928) in 47 volumes serves as a monument to his diplomatic art.

- In contact with 0

- Google+ 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0