Towards the end of the Hundred Years' War, the torment that the French people endured from unemployed mercenaries reached its maximum. Naturally, the first steps were taken in France military reform. A brilliant statesman, a representative of the bourgeoisie that was just beginning to emerge, Jacques Coeur, in 1439, at a meeting of the States General in Orleans, proposed and carried out the following measure: take the best half of the robbing gangs for pay, turn them into standing troops and with their help destroy the other, most debauched and criminal. But the medieval system did not know permanent troops, except for a few bodyguards of the sovereign; the medieval state, which did not collect taxes, did not have the means to maintain a standing army.

Jacques Coeur, proposing to grant the king the right to maintain a standing army and the right to collect taxes from the population for its maintenance, dealt a severe blow to the medieval system and laid the foundation for new centuries, and with them - absolutism royalty. Fear of mercenaries forced him to agree with Jacques Coeur; in 1445, ordinances appeared that legalized the existence of 15 companies. These 15 ordinance (i.e., existing by royal order) companies received an organization responsible medieval tactics; each company consisted of 100 spears, 4 soldiers and 2 servants each (horse and foot together); the former bandit captain (head) who stood at the head of the company began to be called the royal captain.

Each province in which the ordinance company was stationed had to supply it with food. Each spear was supplied monthly with 2 rams and half a cattle carcass; once a year - 4 pigs. In addition, each spear eater received 2 barrels of wine and 11? packs of grain; for each horse there were 4 loads of hay and 12 loads of oats per year; for welding and lighting, each eater received 20 livres per month from the province.

Mercenary was the highest level compared to the feudal militia; but from the internal contradictions of mercenaryism, mobilized only for war, the first standing army of 9 thousand soldiers was born. And the first task of the standing army, born with the advent of peace, was the internal front: the enemy is not external, but internal. Ordinance companies are only the initial stage of the institution of a standing army; it received full development only two hundred years later, in the 17th century, when the European economy rose to the highest level.

Broken spears

While the mounted ordinance companies were a permanent existing unit, all infantry continued to be hired only in case of war, since the state did not yet have the funds to maintain at least infantry cadres in peacetime. The cavalry unit was therefore called at the end of the 15th century “ordinaries”, and the infantry - “extraordinaries”.

It was very difficult to use the bands of French adventurers, due to their lack of discipline and their tendency to riot and robbery. The command of the gangs was entrusted to the most famous, popular, authoritative and experienced knights: for example, the command of 1000 adventurers was entrusted to Bayard - “a knight without fear and reproach”; the latter modestly declared that commanding such a thousand-strong detachment exceeded his strength, and asked to be left in charge of only 500 adventurers. Louis XII at the beginning of the 16th century, he made an attempt to socially strengthen this infantry by assigning 12 poor nobles to each company for double pay. These were the so-called “broken spears” of “Lancia spezzada” - that is, impoverished, disembodied knights who no longer represented real spears.

A spear is a piercing or throwing (total length from 1.5 to 5 m) long-shafted weapon. The weight of the spear is about 4 kg. History, this spear appeared in the Paleolithic era (ancient stone Age) and was originally a pointed stick, later a shaft with a tip. The spear is one of the most ancient types of weapons. Its heyday begins in the Bronze Age, when the advent of metal led to the expansion and diversity of tip shapes. At first, the tip was tied on the outside of the shaft by the shank, later the tip was either worn like a glove and, if there were external ring-shaped ears, it was tightly tied with a cord passed through the ears located in the lower part of the tips. Sometimes he would wedge the shaft himself. Even in the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates, where ancient city-states arose, the military forces consisted of free community members. And the core of this army consisted of adult, respectable husbands, heads of families. They united in a phalanx of several ranks of foot spearmen, covered with shields and advancing shoulder to shoulder. Their blow was irresistible. IN Ancient Rus' the spear was the most common type of weapon. The spearman was the backbone of the Russian army. An experienced warrior threw a spear very accurately. To do this, he needed to practice a lot with targets. The flight range of a spear thrown by hand was 30-40 m.

Destination of copies

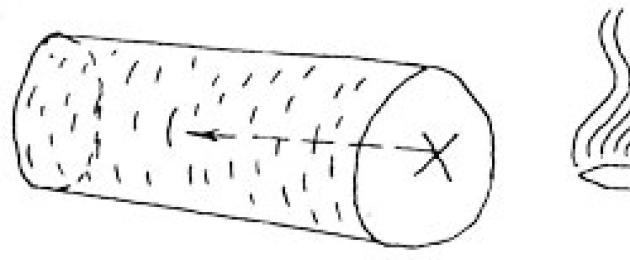

The purpose of the spears largely depended on the shape of their blades. The spear consists of a shaft, a guard, sometimes also called a sword, and an iron or damask tip, which in turn consists of a feather, i.e. blade, tube, or crown into which the shaft is inserted; the neck, the thinnest part between the tule and the feather, and in later copies the apple, the expansion on the neck (Fig. 12). The iron forging in the form of a spear at the end of the shaft, which served to rest on the ground, is called a podtok. To fasten the rod with the tip, two round holes were usually made in the tulle, into which nails were driven. More ancient spears of the XI-XIV centuries. were extremely varied in size and shape: from flat, leaf-shaped to narrow, long, tri- and tetrahedral like a sting.

Rice. 12. Spear.

Long faceted spears became widespread in Russia in the 16th century. due to the reinforcement of the chain mail on the chest and back with solid metal plates - mirrors, which require a stronger blow to defeat. In Novgorod, tetrahedral armor-piercing spears were used in the 14th century. A spear of a transitional shape, already narrow and tetrahedral, but still almost diamond-shaped, was used in the 13th century. From the XIV-XV centuries. An apple also appears, usually absent from spears of the 11th-13th centuries. In the 16th century From the body of the spear, strings or strings begin to extend, reinforcing the shaft of the spear in the upper part. They especially increased in the 17th century, when the spear entered service with the spear companies of the new system. The shape of the tips itself was very diverse. Several types of spear tips can be distinguished. The simple elongated, sting-shaped shape of the tip was most widespread, along with the triangular shape. The tip was put on the shaft and served as its natural and reinforcing continuation. The sting-shaped tips, intended for inflicting deep penetrating wounds, usually had a tetrahedral shape, and a spear with such tips was a common weapon for infantry in regular combat formations. In addition to the tip, the spears had a plume - a colored tail fluttering in the wind, usually made of horsehair, which was attached near the tip and served not only for decoration, but also to absorb and retain blood pouring from the enemy’s wound onto the shaft. The shaft, stained with blood, would slip in the hands, preventing an accurate and powerful blow. The same purpose - to protect the hand from sliding along the shaft - was served by a protrusion located in the center of gravity of the spear and contributing to a more stable hold of the spear during battle.

Another very common tip shape was leaf-shaped.

Such tips had two strongly pronounced flat symmetrical cutting surfaces, smoothly expanding at the beginning and slowly tapering towards the tip like an elongated isosceles triangle. To strengthen the tip and give it greater strength, an additional stiffening rib was stretched along it towards the tip. Wounds inflicted by a spear with a triangular tip were more dangerous - they were wide and caused severe bleeding. At the same time, the tip had less strength and was not intended for piercing armor. Wounds caused by a triangular tip were more dangerous. As we move from bronze weapons to metal ones, the specific weight of spears with such tips increases, because the stronger iron tip compensated for the weakening due to expansion. Diamond-shaped tips were a logical continuation of the idea of expanding the tip blade. Such tips were widely used when hunting wild animals, as well as in the fight between infantrymen and cavalrymen and horsemen against infantry. To inflict a wound with such a spear required significant force, which was developed by a horseman at full gallop, or by an infantryman who rested one end of the shaft on the ground, and pointed the tip at the charging cavalryman’s horse. Often the spears were equipped with a thicker shaft than usual, capable of not breaking off under the weight of the leaning body. In contrast to spears with an expanded diamond-shaped tip and a reinforced shaft, designed for fighting an infantryman with a horseman, a version of a spear with an elongated tip appeared. The dagger-shaped straight blade was especially convenient for cavalrymen who inflicted deep penetrating wounds and were able to use such a spear at a long distance like a sword. From a weapon used for straight piercing movements, the spear gradually transformed into a multifunctional, flexible device for long-range combat using circular, rotational, spiral and other movements, blocks and feints. Since the rider could pierce through the enemy with such a dagger tip, in order to prevent the blade from getting stuck in the body, a limiter was often located immediately behind it, separating the blade from the shaft. To give the tip greater strength, a stiffening rib ran through its center, towards which the blade gradually thickened.

A very interesting type of dagger-shaped blade was a curved blade in the shape of a tapering wave.

The use of a wavy blade has its own characteristics. First of all, the tip is always directed at a certain angle to the horizontal, which allows it to bend around hard surfaces under force and slide off them. For example, a dagger blade, hitting a plaque or a button on clothing, will not go further. The wave-shaped blade will slide off such an obstacle and pass by it, hitting the enemy near the button. Attempts to combine the advantages of jagged or wavy edges with a broad bladed tip have led to numerous variants of spears having two, three or more bulges on wide, leaf-shaped tips. However, unlike wave-shaped blade tips, such jagged tips are more difficult to penetrate deep into the enemy’s body, and once inside, they often get stuck in it. Spears with such tips were preferred to be used for throwing, and riders often tied a strap or rope to the shaft, allowing them to pull the spear back in case of a miss and use the spear again.

Another type of tip that was widespread in medieval Europe was the horn-shaped tip.

This natural form fully met the requirements of strength and reliability. The spear could have a thickened second end, which made it possible to use it as a club, and in addition, made the spear more balanced. The thickening at the other end of the spear balanced the heavy and wide blade of the tip, which was especially important for horsemen. They could place the spear across the saddle and work with both ends. Many peoples used special throwing boards for javelin throwing, which seemed to lengthen the warrior’s arm and, due to the resulting additional shoulder, significantly increased the power of the throw. With the help of a throwing plank, the combat range increased to 70-80 m. In Europe, the importance of the spear as a combat offensive weapon increased sharply with the emergence of cavalry as a decisive force on the battlefield. This process developed very actively in Rus'. The spear became the most important weapon of both noble and ordinary horsemen. The prince, galloping ahead of the detachment and breaking a spear in the heat of battle, was considered a model of military valor. The spear gave the warrior a number of advantages in hand-to-hand combat. It was longer than any other weapon and could be used to reach the enemy faster. A spear thrust provided the essential and easiest method of defeating even an armored enemy. In the Middle Ages, the spear was the most effective weapon of the first onslaught, so the fight between opponents began with the use of a spear. In battle, the spear was used not for throwing, but for striking. At the courts of the feudal lords there were stocks of weapons, including spears. Over time, in the traditional elongated triangular spear, the feather was flattened and rounded, or the center of gravity of the blade was lengthened and moved forward. The streamlined, flowing shape of the blade has received a new expression in laurel-leaf tips. This is how the most powerful of the ancient Russian spears appeared - slingshots, which had a feather width of 5 to 6.5 cm and a laurel tip length of up to 60 cm. To make it easier for a warrior to hold a weapon, two or three metal knots were attached to the shaft of the slingshot. A type of spear was the owl, which had a curved stripe with one blade, slightly curved at the end, which was mounted on a long shaft.

Spearmen

Spearmen were necessary in any army, especially against cavalry, but unlike other types of troops, only the first two ranks took part in battle. They could not hold out against professional warriors for long, but while they held formation, they provided the cavalry with an unpleasant shock. Considerable time and attention was devoted to the training of spearmen in all countries of the world, because the spear was the main weapon in medium-range combat. Riders trained by striking with a spear at full gallop at special targets - at first stationary, but as the training became more complex, moved at variable speeds. A piece of rag, painted with dye, was put on the end of the spear, so that the point where it hit the target was immediately visible. Then they moved on to duels between two warriors using spears with blunt tips painted with paint.

The warrior's art of wielding a spear

The warrior's art of wielding a spear reached exceptional heights in closed monastic schools Ancient China. We also find mention of the spear in Japanese mythology, which claims that the islands of the Japanese archipelago were created by two deities who used a spear for this purpose. This case reflects the significant importance of the spear to the Japanese people and the fact that it was one of the most ancient types of weapons used on the battlefield. The prototypes of the Japanese spear - yari - came to Japanese soil from the Asian continent. The base of the tip of the continental spear was made in the shape of a ball with a recess into which the shaft was inserted. The tip of such a weapon could in some cases - with strong poking and sharp pulling - get stuck in the victim’s body. Therefore, a spear tip was created, secured with a pin stuck into the shaft and secured by winding with a cord. It is this tip that corresponds to the standard Japanese spear, which was most popular at the end of the 13th century in the period after Mongol invasions. In the hands of trained warriors, it was one of the most terrible types of military weapons. Sojutsu - the art of wielding a spear - was often seen as a selfish art, a manifestation of rugged individualism, since death from wounds inflicted by these weapons was usually slow and painful. The wounds inflicted by spears were terrible, since the consequences of an injection were often much greater than from a chopping or cutting blow. To inflict a disabling wound, it was necessary to stick the spear into the body only 7-10 cm. Cutting and slashing weapons often did not penetrate deep enough, but piercing weapons provided an effective injection. But although the spear was a more terrible weapon than the sword, its length and weight required greater strength and endurance for confident action.

Many systems for teaching how to use spears

In this regard, many systems have arisen that teach the use of spears. The usual shaped yari is known as su-yari - a simple spear, or choku-yari - a straight spear, kagi-yari - a key-shaped spear, jumonji-yari - a cross-shaped spear and many others. For each type there was its own system of actions, using the advantages of this particular type. The demands of combat and differences in the tastes of spearmen led to the emergence of a large number of schools of spear art. One of the most dangerous types of yari was the kuda-yari, a tube-spear that uses the shaft to slide through the kuda, a metal tube. It is this spear that is the main one in such a tradition of sojutsu as Owari Kan-ryu. The founder of Owari Kan-ryu was Tsuda Gonnojo Nobuyuki of the Owari clan. The province surrounding the city of Nagoya was also called. The essence of Kuda-yari Owari Kan-ryu was the technique of using kuda - to thrust the spear deeply and sharply pull it out, with maximum control over it. In the Kan-ryu kuda-yari strike, manipulation of the shaft allows the tip of the spear to be inserted not straight, but with rotation, which results in a crane with a diameter of 15 cm. The standard length of the Kan-ryu spear is 3.6 m. This art of spear wielding retained aspects of the style that preceded it, characteristic for an earlier era of Japanese martial culture.

A method for making a spear in modern conditions?

The making of the spear (shaft) has changed little over time. Its technology is very simple. Go to the forest, preferably in winter. You look for an even branch of a suitable size and cut it down. It can be the length from the ground to the tips of the fingers of a raised hand, the thickness is not significant, the main thing is that it is within reasonable limits. The optimal length is 2.5-3 m. The material can be any tree, everything is determined by the region where the person who makes the spear lives. These are ash, hazel, oak, maple, beech, acacia. Pine will not make a very good shaft - the wood is soft, brittle, and knotty. Then remove the bark from the shaft and soak it, straightening it if necessary. To do this, take clamps, clamp it either between boards or between corners and let it dry in a dry place for at least a month. Next, you need to thoroughly clean the surface from knots with sandpaper, otherwise your hands will slip (Fig. 13). The tip can be made soft. Take foam rubber, wrap it around the end of the spear, tighten it with insulating tape, and wrap it tightly with a second layer on top (Fig. 14). The tip can be made a little differently. To do this, clean the end of the shaft on which you will put the prepared tip. Make the tip as follows.

Rice. 13. The first stage of making the tip.

Rice. 14. The second stage of making the tip.

Rice. 15. Finished product.

Necessary items: construction insulation, strong rope or thin wire, knife, hot soldering iron with a thick tip, and optionally, adhesive tape or insulating tape. Then, using a knife, cut a piece of building insulation to the required length (about 10 cm). Using the hot rod of a soldering iron along the longitudinal axis, melt a hole 5-6 cm deep in the insulation. If there is no hot rod, simply cut a corresponding hole. Please note that the edges of the cut may spread further along the cut line, so try to make smaller cuts and do not bring them to the edges of the insulation. Clean the end of the shaft on which you will put the prepared tip. It is advisable to clear the shaft of knots. Place the tip on the shaft and secure it with rope or wire. The fastening rope can be wrapped on top with tape or insulating tape (Fig. 15).

Was this retribution for “sponsorship” assistance in organizing the revolution and the Civil War?

. Writer, historian Nikolai Starikov, author of the books “Chaos and revolutions - the weapon of the dollar”, “1917. The key to the “Russian” revolution,” etc., claims that the Bolsheviks did not forget their benefactors. And although they did not fulfill the “order” for the collapse of Russia, they nevertheless repaid their financial debts with interest.

The Civil War had barely ended when the young Soviet government became seriously concerned about the extraction of the yellow metal. On November 14, 1925, the government of the RSFSR with a light hand (let us recall that this fiery Russian revolutionary of Jewish origin spent about 12 years in the West at the beginning of the twentieth century and even managed to obtain an American passport) transferred the rights to develop gold mines in Eastern Siberia to Lena Goldfields Co. ., Ltd" ("Lena Goldfields"). The same one whose workers, outraged by low wages, were shot in cold blood in 1912. The famous Lena shooting at one time gave the Bolsheviks a reason to stigmatize the autocratic order in Russia. And now the Bolsheviks themselves transferred to the British consortium that owned Lena Goldfields the right to mine gold on the Lena River (and not only there) for 30 years! The concession area covered a vast territory from Yakutia to the Urals, and the interests of the Western company now went far beyond gold mining. Silver, copper, lead, iron fell into their sphere...

Under an agreement with the Soviets, a whole group of mining and metallurgical enterprises was placed at the disposal of Lena Goldfields. What did the country receive in return? A measly 7% of the volume of mined metal.

Colossal riches floated to the overseas uncle for virtually nothing. However, this brazen robbery of the country did not last long. On February 10, 1929 he was expelled from the USSR. And - an amazing coincidence - in December of the same year, Lena Goldfields was forced to curtail its activities in Russia.

Swedish business

Someone will notice: this plunder of the country by foreigners took place after Lenin’s death in January 1924. It turns out that the debts for sponsorship of the revolutionaries were paid by Trotsky alone, who arrived with 10 thousand dollars in his pocket from New York to Russia in the spring of 1917? (By the way, not only he and Ilyich returned to their homeland then. Other “Cossack women” also arrived from the West in revolutionary Russia: V. Antonov-Ovseenko, who later arrested the Provisional Government, the future head of the St. Petersburg Cheka, Moisei Uritsky, after whose murder the “red revolution” would begin terror", V. Volodarsky (Moses Gold-shein) and many others.)

In fact, the Bolshevik government had concluded dubious deals with the West before, even during Ilyich’s lifetime. Perhaps the loudest of them concerned the purchase of steam locomotives from the plant of the Swedish company Nidqvist and Holm.

The volume of the order is amazing - 1000 locomotives at a cost of 200 million gold rubles. This is almost a quarter of the country's then gold reserves! Note that until now this company has not been able to produce more than 40 locomotives per year. And then she was offered to make a thousand! The order was distributed over 5 years: in 1922, Russia was supposed to receive 200 steam locomotives, and in 1923-1925 - 250 annually. Why did the Soviet country, in dire need of railway equipment, stubbornly want to purchase them from this Swedish company and at greatly inflated prices? Why did she agree to wait 5 years for deliveries, instead of buying the right product cheaper and immediately, but in another place? People's Commissariat of Railways, headed in the early 1920s. L. Trotsky dreamed so much about these locomotives that he not only made an advance payment of 7 million crowns, but also issued a Swedish company... an interest-free loan of 10 million crowns “for the construction of a mechanical workshop and a boiler house.”

The Soviet magazine The Economist wrote about the strangeness of this case in early 1922. The author A. Frolov suggested finding out: why did you need to order from Sweden? After all, with such money it was possible to “put your steam-locomotive factories in order and feed your workers.” Before the war, the Putilov plant produced more than 200 steam locomotives per year. Why didn't they give him loans? Lenin really understood the situation. After consulting with Trotsky, he asked Felix Dzerzhinsky to close down the Economist magazine (which had previously published articles unpleasant for the Soviets), saying: “The Economist employees are the most merciless enemies. Get them all out of Russia.” The suspicious contract with the Swedes remained unchanged after the leader's intervention.

How did the Bolsheviks return money to other people's bankers? Just send it to the West and write in the “Purpose of payment” column: “Refund of funds for the Russian revolution and victory in Civil War", obviously, would be impossible. A good excuse was needed. For example, buy something in the West, at least the same locomotives. Trotsky organizes the purchase, but Lenin seems to be aware of the deal and does not interfere with it. Otherwise, the dubious agreement would have cost Trotsky his career.

By the way, many documents confirm that it was through the Swedish banking system that money for the revolution was pumped into Russia. And then they came back through it. Already in the fall of 1918, Isidor Gukovsky, Deputy People's Commissar of Finance of Soviet Russia, arrived in Stockholm. He had boxes full of money and jewelry. The cost of the cargo was estimated at 40-60 million rubles... Millions of rubles were transferred to Stockholm banks, including Olof Aschberg's Nua Banken, whose name often appears in books about the financing of the Bolsheviks.

Deal with the devil

Exact number of contracts and concessions issued Soviet power American firms at the dawn of the construction of a new state are difficult to name. But this includes $25 million in commissions to American industrialists for the period from July 1919 to January 1920, and an asbestos mining concession issued to Armand Hammer in 1921, and a 60-year lease agreement with Frank Vanderlip and his consortium, which provided for the exploitation of coal and oil deposits, as well as fishing in the North Siberian region with an area of 600 thousand square meters. km.

The return of funds allocated for elimination was obviously one of the agreements between representatives of Western governments and the Bolsheviks. Lenin and Trotsky diligently observed this agreement. But the new leaders did not live up to other hopes of the West. Placed at the helm of Russia in order to completely destroy it (and initial stage the goals of the West coincided with the revolutionary dreams of Lenin himself), Ilyich instead began to put the torn country back together. To build a strong and independent state that plays again key role in world politics.

True, the proletarian leader did not live long. I do not rule out that the shot from the Socialist-Revolutionary F. Kaplan, which hastened his death, was some kind of preventive measure on the part of his former foreign guardians - so as not to go too deep. L. Trotsky may have been ready to continue working for the West, but in 1929 Stalin sent him home, and then sent the murderer R. Mercader after him with an ice ax. As we know, no deal with the devil goes unnoticed.

A.V. Kurkin

1. Prerequisites for the creation of permanent military formations in Burgundy in the 15th century.

It is generally accepted that a constant, i.e. existing not only in wartime, but also in peacetime, the Burgundian army appeared in 1471 after the establishment of the so-called. "Ordinance mouths". In reality, the issue of the appearance of regular troops in the Principality of Burgundy is much more complicated. In addition, the term “standing (regular) army” itself is very conditional. So, for example, a certain part of the noble elite of the duchy had their own small “regular troops”. We are talking about guard units (“body archers”, “guard archers”, etc.), which had uniform weapons and equipment, paid for by their lord, and carried out constant service at the court of their master. The garrisons of the main fortresses of the country, who guarded them year after year for an agreed fee, could also be considered regular troops. In this regard French historian Philippe Contamine wrote:

““Standing army” is not a very clear expression, so it is necessary to outline the varieties of such an army. It can be considered proven that at least from the beginning of the 14th century. in a specific territory, if only it was large enough, there were always warriors, armed people capable of maintaining internal order, as well as detaining thieves and murderers, executing the decisions of the authorities and the judiciary and ensuring minimal security within the fortifications.”

Obviously, in a broad sense, the term “standing army” refers to large military formations that have their own institutions of supply, combat training and command. The maintenance of such an army presupposes the presence of permanent ones, i.e. regularly levied taxes and the awareness by the country's political elite of the unconditional advantage of an expensive but stable armed force over the cheaper and less controllable formations of feudal militia, city militia and mercenaries recruited from time to time. The events of the Ghent War (1452-1453), which required the Burgundian military-political leadership to keep large military forces in the field for two years, and strong garrisons in the cities of the rebellious provinces, prompted the Burgundian Duke Philip the Good to look for alternative options feudal militia.

In 1457, from the volunteers - volunteers(volontaires) the first permanent Burgundian companies were recruited, which received half pay for service in peacetime. The companies had different numbers and were divided into chambers of 5-6 gendarmes with several companions in each. Once a month, three-day company training sessions were held, at which weapons and training were checked, and salaries were also issued. For 3 days of training, the gendarme was awarded 24 sous (2 Flemish gros), the companion - 6 sous. Most likely, such volunteer companies did not last long.

In 1466, infantry units were created in Burgundy, especially in the lands bordering the ever-rebellious Principality of Liege economic(mesnagers), somewhat reminiscent of the French “free archers”. Household workers garrisoned several fortresses and combined service with conducting personal affairs.

In 1467, after the Battle of Brustem and the capitulation of Liege, the Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, again decided to revive the volunteer companies. Thus, according to a message from Jean d’Haenin, the Duke offered Jacques de Luxembourg, Seigneur de Fienne, and several other seigneurs to lead permanent companies of 50 spears with half pay in peacetime. Luxemburg diplomatically replied that he himself was ready to serve the Duke in any capacity and at any time, but first he must consult with the people of his company. During the meeting, most of the gendarmes of Fienne spoke out against the service, citing fatigue, concern for the families left behind and, most importantly, delays in payment of salaries, which were usually practiced by both Philip the Good and his son. Nevertheless, as Henin concludes, some of the gendarmes nevertheless signed up as volunteers and immediately received their salaries within 15 days.

However, these half-measures could not solve the main problem, which was the extremely clumsy mechanism for mobilizing the Burgundian army, which both negatively affected the timing of the campaign and did not allow timely response to sudden military threats. For example, the gathering of the Burgundian feudal militia (Aryerban) for the campaign against Liege in 1468 lasted for 2 months, while some of the troops never arrived at the rendezvous point, as a result of which the campaign was carried out in difficult conditions of rainy autumn and cold winter.

In addition, Charles the Bold was probably somewhat impressed by the regular army of Louis XI, with which he pitted his feudal army at Montlhéry (1465). Only thanks to regular ordinance companies, during the war of the League of Public Welfare, the French king was able to strike a preemptive blow against one of the League members, the Duke of Bourbon, and knock him out of the fight before the main forces of the Leaguers arrived. After the signing of the Peace of Conflans, the French royal army, battered by the Burgundians at Montlhéry, nevertheless, in two winter months of 1465-1466. during a lightning campaign, she again restored Louis's power in Normandy. Such combat activity and mobility were impressive.

In the fall of 1469, Karl the Bold was in completely fair confidence regarding new war with France, which was to begin in the very near future. For some time, the Duke pinned his hopes on the corps of Italian mercenaries: Prince Rodolfo Gonzaga was offered to recruit 1,200 spears (5 horsemen each), divide them into companies and send them to Burgundy for service. However, due to insufficient funding and political tensions, this plan failed.

In 1470, the problem of creating a regular army arose with all its urgency. On May 20, a decision was made to recruit 800 copies of the “ordinance”; on October 23, the number of “copies of 3 horses” recruited into the regular army increased to 1,000, with a payment of 15 francs monthly. It was from this moment that the formation of the first Burgundian ordinance companies began, which formed the backbone of the standing army of Charles the Bold.

In the winter of 1470-1471. The Duke's military officials began to inspect the emerging companies. So, on February 9-11, three commissioners of the duke conducted a review of the Burgundian company of the knight Ame de Rabutin, lord d'Epiri.

On February 10, a review was held of Peter von Hagenbach's company, temporarily stationed in Wavre. Hagenbach himself, busy with the administration of Alsace, was absent, so the company was actually led by his lieutenant Jean d'Yin.

On February 27, the ducal commissioners inspected Claude de Dammartin's company. During the review, the company commander and two foreman-disaniers were absent, so the company was commanded by Philippe de Saint-Léger, lieutenant and commander of the second disanier.

In May, government officials in Brabant received instructions from Charles the Bold to register volunteers for enlistment in permanent companies. It was necessary to recruit 1,250 spears consisting of 1 gendarme, 1 pikeman, 1 crossbowman and 1 culverinier - a total of 5,000 people. The fighters recruited in this way were ordered to be concentrated in Arras by June 15. However, the deadlines were not met, and the registration of volunteers stretched until the end of the year.

2. Military orders of Charles the Bold.

On July 31, while in the city of Abbeville on the Somme, Charles the Bold issued his famous decree (ordinance) on the formation of 12 regular companies.

“Monsignor the Duke announces that he is taking for his maintenance and support 1,250 gendarmes of the ordinance with three horses, and for each gendarme three horse archers and a foot crossbowman, a culverinier and a pikeman, the best and most trained that he can find in his lands on rights Señora."

Each ordinance company (compagnies d'ordonnance), according to the provisions of the Abbeville Ordinance, consisted of 100 copies, consolidated into 10 platoons - design(dixains - tens). Each design consisted of 10 copies, divided into two unequal chambers - chambray 4 and 6 copies each. Commander of the Quartet - chefdéchambre(chefe de chambre) was subordinate to the commander of the “six” - design(disenier - foreman), who, in turn, was directly subordinate to the company commander - air conditioning(conducteur, in the Russian-speaking tradition - conductor or conductor). The conductor carried out the orders of the commander-in-chief - the General Captain, i.e. Duke Charles himself, who, according to Olivier de La Marche “I wanted to be the only captain of my people and order them at my pleasure.”

Thus, the Burgundian order company included 900 people, of which 100 were non-combatants - pages or jacks. The combatants included 500 cavalry (100 gendarmes, 100 coutiliers and 300 horse archers) and 300 infantry (100 crossbowmen, 100 culveriniers and 100 pikemen). In general, copying the organizational structure of the French ordinance companies, Burgundian military functionaries, in the Italian manner, reinforced the traditional lance of 6 cavalry (including a mounted servant) with three infantry.

Each company was assigned 1 or 2 trumpeters - trompette(trompettes), surgeon, commissioner, keeping order (commissaire), notary nother(notaire) and treasurer- treasure(tresorier), otherwise dressed(auditeur, auditor) with an assistant who issued a salary once a quarter based on the following monthly payments:

The absence of a reveler and a page in the above list should not be confusing, because their salary was counted in the 15-18 francs that were given to the gendarme.

In fact, 12 ordinance companies (in reality, 13 companies were formed, but company No. 1 was immediately assigned to the guard) completed their formation and “became operational” already in 1472.

- Company No. 1, Conductor Olivier de La Marche;

- Company No. 2, conductor Jacques de Garchier;

- Company No. 3, Conducto Jean de La Vieville;

- Company No. 4, Conducto Jacques de Montmartin;

- Company No. 5, Conducto Giacomo de Vishy;

- Company No. 6, Conductor Philippe de Dubois;

- Company No. 7, conductor Gilles de Garchier;

- Company No. 8, Conducto Jacques de Rebrenne;

- Company No. 9, Conductor Claude de Dammartin;

- Company No. 10, Conductor Peter von Hagenbach;

- Company No. 11, Conducto Baudouin de Lannoy;

- Company No. 12, Conducto Hame de Rabutin.

- Company No. 13, conductor Philippe de Poitiers.

The national composition of the formed units was quite varied. Thus, companies No. 1, 13 consisted mainly of Picardians, companies No. 2, 3 - from Flemings, companies No. 4, 7-12 - from Burgundians, company No. 5 - from Savoyards, company No. 6 - from Dutch. Often, the actual command of the companies was carried out not by the conductos themselves, many of whom occupied important government or court posts and were forced to constantly be distracted from solving narrowly military tasks, but by their lieutenants. Some of these lieutenants, such as Jean d'Ygne, Antoine de Sallenowo or Ferry de Cousens, eventually replaced their immediate superiors and themselves took up the position of conducto.

On November 13, 1472, in the town of Boen-en-Vermandois, the next military order of Charles the Bold was issued. The ordinance took into account the results French campaign and contained a minor adjustment to the size of the regular army of Burgundy:

The administrative division of the company into dizani, cameras and spears in battle and on the march, as follows from the text of the ordinance, was leveled. The company's fighters in field combat conditions were divided into three tactical units: a cavalry detachment of gendarmes and revelers, a detachment of archers and a detachment of infantrymen. Thus, the command functions of the directors and chiefs of cells were in demand only at the station, to resolve everyday and judicial-administrative issues. Each tactical unit on the march and in battle was controlled by gendarmes specially appointed by the company commander for this purpose.

The new ordinance also described in more detail the marching order of the company, its quartering, and clarified some elements of subordination. So, preparing for the march, the soldiers, at the first signal of the trumpets, rolled up their tents and packed their belongings, at the second signal, they gathered in units, at the third signal, they formed a common column and set out on a march. A mandatory roll call was introduced for all company soldiers, in connection with which the gendarmes provided lists of their people to the direct disagnies, who then at the command of the conductor, who, in turn, forwarded the complete list of the company to the military department, and kept the duplicate with him. In addition, the procedure for punishment for certain offenses was simplified, and decisions on fines were made locally, both conducto and disagne.

Dramatic changes in the organization of regular companies occurred after the issuance of the Saint-Maximin Ordinance in Trier (October 1473):

“The highest, noblest, most powerful and fearless Monsignor Duke of Burgundy, Brabant and others. Having an indefatigable zeal and desire to secure, protect and increase the welfare of the duchies, counties, provinces, lands and estates, which by natural right passed from his noble ancestors under his suzerainty, and in order to protect them from the encroachments of enemies and all who envy the welfare of the noble House of Burgundy, as well as those seeking by force of arms or criminal acts to undermine the wealth, honor and integrity of this noble House and the said duchies, counties, provinces, lands and estates, just as some time ago, formed and established companies of the ordinance, gendarmes and riflemen and others, mounted and foot soldiers, who, like other people, cannot constantly remain in obedience and good behavior without law and instructions, which describe their duties for maintaining discipline and virtuous order, as well as for punishing and correcting their shortcomings and mistakes. Therefore, our fearless monsignor, after leisurely, long and mature reflection, developed and approved the following laws, statutes and regulations.”

From now on, the company consisted of 4 squadrons - squadrons(escadres), which in turn split into 4 chambers of 6 copies each. The 25th squadron spear was the personal spear of the squadron commander - squadron chief(chief d'escadre). Three of the four squadron chiefs were appointed by the conductor, the fourth by the duke, usually from among the squires of his Hotel.

At the beginning of the year, the conductors were notified of their assumption of office and took an oath of allegiance to the duke. Next, the conductor formed companies and compiled lists of military personnel, which they provided to the Duke at the end of the year. At the same time, during a special ceremony, the conductor was presented with command batons, duplicates of the ducal ordinance with the necessary instructions and copies of their company lists. At the same time, the Duke personally greeted each conductor, promising timely cash payments, and assuring of his absolute desire to extend the contract in the future.

The paragraphs of the ordinance further tightened discipline: soldiers were forbidden to blaspheme, swear, or play dice. The Duke’s attempt to instill carnal abstinence in his soldiers looked no less utopian: the numerous prostitutes who accompanied the soldiers on campaign or at camp should have been dispersed, leaving only 30 of them for each company.

The section devoted to conducting exercises looked more sensible: soldiers were trained to master tactical techniques, taught how to interact on the battlefield, and practiced combat formations.

However, the Saint-Maximin Ordinance was soon supplemented by several instructions, the text of which has not been preserved. We can judge the changes that have occurred in the organizational structure of the companies in comparison with the provisions of the Saint-Maximin Ordinance, thanks to the reports of Olivier de La Marche.

In 1474, while with his company in the ranks of the Burgundian army that besieged Neuss, La Marche wrote his famous treatise “Services of the Hotel of Duke Charles of Burgundy the Bold”, in which, among other things, he left valuable comments regarding the organizational structure of the ordinance companies:

“The Duke /has/ one thousand two hundred gendarmes of his ordinance, each of whom has an armed reveler, and under /the command/ of each gendarme there are three horse archers, in addition, each gendarme has three foot soldiers armed with crossbows, culverins and pikes: thus, in the spear /counts/ eight combatants, but the foot soldiers are not controlled by their cavalrymen.”

About who “controls” the infantrymen, La Marche writes in another paragraph:

“So, we should talk about the service of the infantry, which is controlled by the knight, the chief of all the infantry, and /his/ deputy, who is responsible for all the infantry conductors. Each company has three categories of infantry, there is a captain, a mounted gendarme and a standard bearer with a guidon; and for every hundred people there is a mounted gendarme-centurion, who carries another, shorter flag..., in addition, for every thirty-one people there is one, called a thirty-man, to whom all the others are subordinate.”

Thus, according to La Marche, the company infantry was divided into 3 hundreds under the command of centurions - Santanye(centeniers), each of whom commanded thirty -trantanye(trenteniers). Each thirty was divided into 5 copies of 2 pikemen, 2 culveriniers and 2 crossbowmen in each. The general leadership of the company infantry was carried out by chefdepier(chef de pied). Horse archers along La Marche were consolidated into 4 squadrons of 75 people each. On the march and in battle, these units acted separately from the gendarmes.

Unfortunately, neither the authors of the Saint-Maximin Ordinance nor La Marche indicate how the positions of commanders of squadrons, cells, hundreds and thirty in a company were related. We can only assume that some of them were combined. For example, the commander of the first squadron was also a lieutenant (deputy conductor) of the company, the commander of the second squadron was also in command of all the gendarmes and kutiliers of the company, the commander of the third squadron controlled all the archers, and the commander of the fourth squadron commanded the infantrymen, i.e. combined the position of chief deputy. Each of the 4 squadrons of gendarmes may have been commanded by lieutenants (deputies) of squadron commanders from among the cell commanders. Other chamber commanders could concurrently hold positions as commanders of squadrons of archers and infantry squadrons. Total number commanders of various levels in the company, including the conductor, according to La Marche, there were 24 (5 for gendarmes, 5 for archers, 13 for infantrymen). Based on the premise that all command positions were occupied by gendarmes, we must admit that in this case at least 18 heavy cavalrymen of the company (commanders of archers and infantrymen) were distracted during the battle by solving tasks that were not typical for cavalry.

One way or another, such a multi-layered and cumbersome system of company hierarchy apparently significantly complicated the process of managing people during the march and battle. Each of the infantrymen and archers of the company had several immediate superiors: during the battle they were commanded by some people, on the march by others, and others sent them on leave. Burgundian military functionaries could not help but understand that the lowest administrative unit “spear”, inherited from the Middle Ages, which united fighters called upon to solve completely different tasks on the battlefield, was hopelessly outdated. Obviously, there was only one way out of the administrative-tactical impasse: it was necessary to divide the company fighters into 3 administratively independent parts - cavalry, archers and infantry. However, due to objective reasons, this process dragged on until 1476, when it was too late to change anything.

In May 1476, in Lausanne, Charles the Bold issued another military ordinance, in which he finally tried to eliminate the administrative and tactical contradiction arising from the isolated position of the infantry. From now on, the infantrymen were completely withdrawn from the companies and formed separate infantry detachments (enfants pied, 4 in total) of 1,000 people each. Each detachment was divided into hundreds, under the command of Santanier. Hundreds are divided into quarters quarts under command quartonnier(cuartonniers). The quarts were divided into cells of 6 people (probably 2 pikemen, 2 culveriners and 2 crossbowmen or archers), commanded by the chief deschambres. In battle, infantry detachments were divided into two parts of 500 people each and formed in two lines, one after the other. According to the Lausanne Ordinance, companies consisted of 100 spears and 300 archers. At the same time, the archers received a separate organization from the gendarmes and were divided, like infantrymen, into hundreds, quarts and cells. The division of the gendarmes retained the features prescribed in the Saint-Maximin Ordinance: 6 spears (in 1 spear - a gendarme, a reveler and a page) made up a cell, 4 cameras made up a squadron, 4 squadrons represented the cavalry of a company.

The ordinance was mostly devoted to tactical (combat formation, marching order, field camp arrangement) and disciplinary issues:

"Under fear death penalty The Duke forbids any person, no matter his rank or position, to leave the quarter of the camp that was assigned to him as an apartment, or to leave his detachment during a campaign, even in the absence of the enemy. It is also prohibited to take food and other supplies without paying a certain amount; This is how it should be done in an enemy country. Our dear Englishmen, whose service /Duke/ values, should not be subjected to insults or other harassment. Enemy women and children should be treated with respect. Rape is punishable by death. Also, under /fear/ of severe punishment, soldiers are forbidden to swear in the name of God, the Holy Evangelists and to blaspheme. All women of easy virtue must leave the camp before the start of hostilities."

The Lausanne Ordinance (preserved in Italian translation thanks to a copy dated May 13 by the Milanese ambassador Giacomo Panigarola) was the last major military decree of Charles the Bold known today. Only indirect evidence remains of the subsequent reorganization of the Burgundian army.

Thus, according to the reports of the military treasury, Karl the Bold in 1476 carried out the final division of his troops by type of weapon. All gendarmes were consolidated into 12 companies of heavy cavalry (100 soldiers per company), all horse archers - into 24 companies of light cavalry (100 soldiers per company). The Ordinance infantry was consolidated into three corps of 1,000 soldiers. The buildings were still divided into hundreds, quarters and chambers.

3. The process of forming ordinance companies.

In fact, the conductios appointed by the Duke commissioned companies a year after their appointment. For example, throughout 1471, the ordinance companies were replenished with recruits and gradually brought their quantitative composition closer to the declared standards, which were officially announced in the Abbeville Ordinance. Thus, the composition of Olivier de La Marche's company, stationed in January 1472 in Abbeville, included 9 designiers, 10 chief dechambres, 79 gendarmes, 293 horse archers and 160 infantry (94 pikemen, 34 culverigniers, 10 crossbowmen and 22 foot archers). Gradually, La Marche's company was completed and became operational (see table data).

TABLE. List of personnel of companies No. 1, 2, 3 in 1472.

Company number |

air conditioning |

Spears about three horses |

Horse Archers |

Pikemen |

Coulevrinier |

Foot riflemen |

Total |

Olivier de La Marche |

|||||||

Jacques de Garchier |

|||||||

Jean de La Vieville |

The companies were formed from volunteers who arrived at collection points, passed a screening commission and were enrolled in the unit.

Thus, in the journal for registering the arrival of recruits for the formation of company No. 18 (Conductor Jacques de Dommarien), which was kept by the bailiff of Aval Guy d'Uzy, for three days in February 1473 it was written:

- February 18: 1 gendarme with 4 horses, 4 Picardy archers;

- February 19: 6 gendarmes, each with 4 horses (2 gendarmes from Burgundy, 2 from Lorraine and 2 from Picardy), 2 Lorraine crossbowmen;

- February 20: 2 gendarmes, each with 4 horses, a squire from Chatillon with 4 horses, etc.

- On March 15, 1473, the duke's commissioners checked how the recruitment of company No. 19 (conductor Jean de Jaucourt, seigneur de Villarnoy) was progressing: 44 gendarmes and cranequiniers, mostly from Savoy. Also in the recruiting company, 2 of the 4 positions of squadron chief were occupied - by Antoine de Sallenovo (in 1476 he would lead company No. 10), a knight, and Jacques de La Sera, a squire. At the same time, the other part of the formed company stood as a garrison in the castle of Chatillon.

The shortage of volunteers could be covered by the feudal conscription. For example, in 1475-1476. The nobles of Walloon Flanders set up an Arrièreban to conduct military operations in Lorraine, as well as to saturate the garrison units in Picardy. The document contains the following entry:

“The lord de Wavrin, an old knight, wishing to serve the monsignor /duke/, sent his bastard to Lorraine, accompanied by three gendarmes and six horse archers; of these, six archers were sent to Saint-Quentin in the order under the command of Monsignor de Ravenstein.”

We are probably talking about Ordinance Company No. 6, whose commander, Bernard de Ravenstein, strengthened his riflemen at the expense of the feudal militia.

By the end of 1475, the Ordinance troops of Burgundy (including Italian contingents) included 20 companies. To higher listed compounds the following have been added:

- the Burgundian company of Josse de Lalin;

- the Burgundian company of Louis de Soissons;

- Italian company Nicola de Montfort;

- Dutch company of Louis de Berlaymont (disbanded in 1475);

- the Italian company Trualo da Rossano (in December 1475 it was transformed into the companies of Alessandro da Rossano and Giovanni Francesco da Rossano);

- the Burgundian company of Jean de Dommarien;

- Savoy company of Jean de Jaucourt;

- Spanish-Portuguese company of Denis of Portugal;

- John Middleton's English company (was transferred to the guards);

- Italian company of Rogerono d'Accrocciamuro;

- Italian company of Pietro di Legnano;

- Italian company Antonio di Legnano.

The composition of the companies, especially the Italian, Dutch and English contingents, often did not coincide with the declared standards. The English company initially consisted of 100 gendarmes and 1,600 archers. Louis de Berlaymont's company consisted of 50 lances, 200 archers and 400 pikemen from Holland. Italian companies, as will be discussed below, also often did not meet the standards for numbers and composition. However, by December 1475 the number of company copies was brought to the standard hundred.

Despite the difficulties associated with recruiting and financing the ordinance army, its share in the armed forces of the principality steadily increased. At the end of 1472, a little more than a third of the entire Burgundian army consisted of soldiers on permanent pay. Thus, Chancellor Guillaume de Hugon in his report indicated that the “Army of Burgundy” included 1,200 copies of the ordinance, 1,000 copies of the feudal militia for the field army and 800 - 1,000 copies of the garrison troops. By the end of 1475, the regular army already accounted for two-thirds of all the armed forces of the principality and continued to increase its share. At the very beginning of 1476, three more ordinance companies were formed:

- Italian company of Ludovico Tagliani;

- the Flemish company of Josse d'Hellune;

- Italian company D. Mariano.

4. Armament and equipment of ordinance companies.

The armament and equipment of the soldiers of the ordinance company were spelled out in detail in the Abbeville Ordinance (the texts of the Boin-en-Vermandois and Saint-Maximin Ordinances slightly adjusted the original standards):

“The gendarme must have a full set of white harness, three good riding horses worth at least 30 crowns; he should have a war saddle and a chanfrien, and on the sallet the feathers are half white, half blue, and the same on the chanfrien. Without prescribing armor for horses, the Duke notes that he will be grateful to the gendarme who gets this /armor/

The gendarme's cutler must be armed with a steel breastplate or steel belly (?) on the outside and a brigandine on the inside; if he cannot have such armor, then he should have chain mail and a brigandine on the outside. In addition, he should have a salad, a ring necklace, small upper bracers, lower bracers, and plate gloves or gauntlets, depending on the armor he will be using. He must have a good dart or half-spear with a handle and a stop, and with it a good sword of medium length, straight, which he can hold with either one or two hands, as well as a good dagger, sharpened on both sides and half a leg long

The archer must ride a horse worth at least 10 crowns, dressed in a jacket with a high collar replacing a ringed necklace, and with good sleeves; he must have a ringed garment or a coat of chain mail under a jacket, which is made of no less than 12 layers of fabric, 3 of which are waxed, and 9 are simply sewn. To protect his head, he must have a good lettuce without a visor; in addition to a strong bow and a bunch of 2 and a half dozen arrows, he must be armed with a long two-handed sword and a dagger, sharpened on both sides and half-length

Foot culveriniers and crossbowmen must have chain mail. A pikeman must have a choice between jaque and mail, and if he chooses mail, he must also have a breastplate (glacon)."

Usually, the gendarme armed and supplied his assistant, the reveler, with a horse, and also supplied his page with a horse (sometimes the gendarmes equipped archers). Warriors of all other listed categories had to arm themselves, mainly at their own expense. But there were also centralized supplies of weapons, mainly related to ammunition and siege equipment:

“The artillery service, which the Duke ordered to be ready by April 1, 1473, taking into account past purchases for this purpose, must provide:

200 wuzhes, 1,600 lead hammers without blade and tip, 1,000 other lead hammers with blade, tip and hook, 4,000 forged pikes, 600 slingshots, 600 wooden blanks /shafts/ for ash darts, 1,200 ash blanks for shafts of powder loads /priboynikov or shuffle?/, 600 blanks for half-copies, of which 300 are from willow and 100 from spruce, shuffle 800, 300 forged shovels, 150 iron shovels, 300 wooden non-forged shovels, 800 crowbars and 600 hoes, 500 axes of two species, 300 sickles of two types, 3,030 bows made from wood purchased by the Duke and consisting of 4,300 blanks of yew wood, 600 old bows repaired, 600 feet of Antwerp rope, 100 salads repaired, 253 huvettes (?), 287 vuzhes, 623 pairs /tips?/ of spears, 172 chain mail, 172 gorgets, 80 chapels, 98 crefs (?), 17 hand mills, 50 old bow shafts, 100 purchased new bow shafts, 50 cases with a lid and 100 other cases without a lid, so that store the mentioned arrows and bowstrings and spindles /i.e. arrows for krenikin/, 50 small boxes for packing lead for serpentine, 15 lanterns, 200 wicks for lanterns, 80 carts, 200 repaired ribbed pavois, stored in Arras, covered with leather and oil painting in white and blue with the red cross of St. Andrew; purchased 120 hanging /with straps?/ pavois and 120 repaired others; purchased 4,000 shields of the Lombard type, painted in white and blue with the red cross of St. Andrew and gold flints, purchased 50 ribbed pavois, painted in black, in order to cover sappers<…>»

In May 1476, Charles the Bold ordered the purchase of several thousand pikes for his army in Lausanne.

5. Unification of ordinance companies. Liveries and flags.

Mass clothing of military contingents medieval Europe, bearing one or another unification heraldic symbolism, is usually called liveries(livree, from Latin liberare - to free, to endow). In French texts of the second half of the 15th century. we find analogues of this term - coat(paletot or paltot) and journalade (journades). This or that type of clothing, endowed with heraldic symbols, also turned into a livery. Therefore, in the chronicles and archival documents There are many references to livery robes, jackets, hooks, aketons (octons), etc.

The main unification sign placed on the liveries and weapons of Burgundian soldiers in the 15th century was the St. Andrew's Cross, first red (under John the Fearless), then white (under Philip the Good) and again red (under Charles the Bold). La Marche, in his Memoirs, gave a legendary story about how the St. Andrew's Cross became the main symbol of the Burgundian rulers:

“After the death of the first Christian king of Burgundy, Etienne, his son, reigned, who was king of Burgundy for fifty years. Obeying the will of Magdalene / those. New Testament Mary Magdalene/ and being a good Catholic, he ordered the cross to be delivered from Marseilles, on which the sacred body of Lord Saint Andrew was crucified... And as a sign of admiration for the Lord and respect for Saint Andrew, this King Etienne raised this cross over his army in many battles and wars. From that time on, it became customary among the Burgundians to honor the cross of St. Andrew with their sign.”

In fact, a piece of the cross of St. Andrew appeared in Burgundy under Philip the Brave, who received this relic from the monastery of St. Victor in Marseille. The image of the St. Andrew's cross as a military unification sign was probably first used by the Burgundians at the Battle of Aute (1408). More precise information regarding the use of the image of the scarlet St. Andrew's Cross by Burgundian soldiers dates back to 1411, when open armed struggle began between the Armagnac and Bourguignon parties. At the same time, the French royal troops supporting the Burgundians “they took off the straight white cross, which was the true sign of the king, and adopted the cross of St. Andrew, the motto of the Duke of Burgundy”

In Article No. 33 of the Treaty of Arras (1435), the French king officially recognized the right of Burgundian soldiers to wear the cross of St. Andrew, regardless of which united army they were in. this moment were. If earlier the Burgundians who fought in the ranks of the French royal army were theoretically obliged to carry a straight white royal cross on their clothes and banners, then from now on their permanent emblem became the “oblique” St. Andrew’s cross, which was called the “Burgundian” cross.

The cross could be made up of either straight crossbars or knotted rods (the so-called “stumpy cross”). The latter style of the cross probably served political propaganda purposes and reflected the emblem of Orleans in the form of a knotted staff.

In 1471, the Abbeville Ordinance legalized the white and blue mi-parties and the red St. Andrew's crosses among the various military contingents of the ordinance companies:

“The archers and revelers will receive from the Duke for the first time a two-color blue and white coat, divided by mi-parti, and then they must dress in a similar way at their own expense. They may wear these coats in the presence of a lieutenant and wear them with the standard of a captain. The Duke also gives the gendarmes for the first time the cross of St. Andrew made of scarlet velvet, which they will attach to the white harness and which they will subsequently replace at their own expense.”

It is interesting that the text of the ordinance does not contain a direct indication that red St. Andrew's crosses were sewn onto the soldiers' liveries. At the same time, there is a sufficient amount of written and visual evidence confirming compliance with the decree of 1435 on the mandatory wearing of the St. Andrew's Cross on soldiers' clothing. For example, in 1472, the magistrate of Lille paid for the supply of material for the liveries of his militia sent to the contingent of the bastard of Burgundy: “forty missing pieces of cloth, half blue, half white, 14 sous 6 denier for one piece(aun is a measure of length equal to approximately 1.2 m.) for the coats of forty archers, pikemen and pioneers..., and one he with half a scarlet / cloth / at 16 sous for one he, to use for the cross of St. Andrew for these coats"

Ordinance companies, according to the message of the English herald-Pursivan Blumenthal, who saw them in September 1472, had 3 flags: "every one From the spearmen / those. company of gendarmes / had a standard and two pannons, one pannon for the revelers riding in front, the second for the infantry and a standard for the spearmen.”

In November 1472, the Ordinance of Bohin-en-Vermandois structured the flags of the regular companies. The main company flag, as before, remained the standard of the company commander - the conducto. Gendarmes and revelers gathered around him on the march and during the battle. The company also had two guidons: a large one for horse archers, and a small one for infantrymen. In addition, each of the 10 company dizanes had two cornets, probably also of different sizes: the first for horse archers, the second for infantrymen. Thus, the company should have had 20 cornets, 2 guidons and 1 standard.

In 1473, the Saint-Maximin Ordinance changed and at the same time streamlined the use of flags in the ordinance companies:

“The flags of different conductos will be of different colors. The cornets of each company will be the same color. First / those. cornet of the first of four squadrons of the company / will carry a large gold C, the second - two SS, the third - three SS, the fourth - four SS. Cell commanders' parcels / four in each squadron / will be the same color as the squadron's cornets. The first banderole of the first cornet will bear one C of gold and below 1; on the second parcel there will be one C and below 2; on the third - one C and below 3; on the fourth - one C and below 4. The parcel of the second cornet or squadron will four times carry two SS and below numbers 1,2,3,4, according to the chambers. The third squadron's parcels will all carry three SSS and below, according to the cameras, numbers 1,2,3,4. The parcels of the fourth squadron will carry four SSSS and, according to the cameras, numbers 1,2,3,4.”

In addition to 4 cornets and 16 parcels attached to the helmets of the cell commanders, each company retained the main standard and one guidon. According to La Marche, in 1474, gendarmes and revelers gathered under the standard on the campaign and in battle, and horse archers gathered under the guidon. La Marche made his recording in the siege Burgundian camp near Neisse. Another valuable eyewitness testimony dates back to the same time:

“At that time, the Duke had a large standard with the image of St. George, as well as various guidons and cornets for parts of the court troops, guard archers and twenty ordinance companies; The standard of the first company was golden with the image of St. Sebastian, as well as the duke's motto, flint, flint, flame and the cross of St. Andrew. 2 - image of St. Adrian in an azure field, 3 - image of St. Christopher in a silver field, 4 - St. Antoine in a red field, 5 - St. Nicholas in a green field, 6 - St. John the Evangelist in a black field, 7 - St. Martin in blood red, 8 - St. Hubert in gray, 9 - St. Catherine in white, 10 - St. Julian in purple, 11 - St. Margaret in beige, 12 - St. Avoy in yellow, 13 - St. Andrew in black and purple, 14 - St. Etienne in green and black, 15 - St. Peter in red and green, 16 - St. Anne in blue and purple, 17 - St. James in blue and gold, 18 - St. Magdalene in yellow and blue, 19 - St. Jeremiah in blue and silver, 20 - St. Lawrence in white and green.”

|

||

|

||

|

Rice. 6, 7. Standards and cornets of the Burgundian Ordinance Companies, 1472-1475. |

||

Based on the above text, as well as an analysis of the surviving Burgundian flags and their painted copies, we can conclude that each order company was assigned a certain “supervising” saint - a practice that was generally common for European armies of that time: just remember “ Detachment of St. George" and "Detachment of the Banner of St. George" of the Italian condottieri Visconti, Landau, Urslingen and Barbiano, the brotherhood of the crossbowmen of St. George, the archers of St. Sebastian and the culevrinier of St. Barbara of the Flemish and Belgian urban communes or the French ordinance companies under "heavenly patronage" of St. Michael.

Another constant component of company flags was the motto and flint - either with the cross of St. Andrew (on the standards of the gendarmes and the cornets of the infantry?), or crossed arrows (on the guidons and cornets of the archers?) which demonstrated the company's affiliation with the House of Burgundy. The company conductor, if he was a banneret, brought into the regulated “pattern” of his unit only his “livery” color - it is in this vein, in my opinion, that the phrase of the ordinance should be interpreted: “The flags of different conductos will be different colors.” For example, in the position of conductor of company No. 13 (Probably St. Andrew) in the period from 1472 to 1477. Three people managed to visit: Philippe de Poitiers, Jean de Longueval and Fanaseoro di Capua. The colors of the flags of St. Andrew changed at least three times: black-violet, white-blue and yellow-white. The colors of St. Peter's flags changed at least three times: red-green, green and red. Moreover, it is known that in the post of conductor of company No. 15 (probably St. Peter) in the period from 1473 to 1477. Walerand de Soissons, Louis de Soissons and Philippe de Loyette stayed in turn.

In the “Lucerne Book of Flags” (Bern Historical Museum) 4 identical white and blue guidons of St. Anne, St. Trinity, St. Hubert and St. Andrew, captured at Murten, are copied. What caused such an extraordinary, emphatically ducal coloring of the flags? We can only guess.

Another mystery: the vast majority of Burgundian cornets known today contradict the provisions of the Saint-Maximin Ordinance. Contemporary researcher Nicolas Michel wrote in this regard:

“Unfortunately, the author has not found a single flag on which the numbers and letters denoting a company and a squadron would have been applied in strict accordance with the rules set forth in Ordinance 1473; perhaps these rules had been changed by the time the flags were captured, or the artist copied the symbols incorrectly in the 17th century.”

At the same time, the Burgundian flags are clearly subordinated to a certain system. Thus, many of them depict regulated symbols in the form of the letters “C”, Latin numerals and small rhombuses (I will denote them with the symbol *): cornet of St. James the Younger “*I**”, cornet of St. Bartholomew “C”, St. Andrew's cornet "VIIJ", St. Philip's cornet "C/VI" (red field), another St. Philip's cornet "C/*III*" (white field), two white and blue cornets (guidon?) St. George (?) “*III*” and “II”.

The "Friborg Book of Flags" (Friborg Archives) contains an image of a Burgundian cornet (or a fragment thereof), on the red field of which, immediately after the golden St. Andrew's cross, three intertwined letters "C" are placed. This flag, and perhaps even the aforementioned cornet of St. Bartholomew, can only be considered as examples of more or less accurate implementation of the instructions of the Saint-Maximin Ordinance. The numbers “VIIJ” and “VI” indicate that there were clearly more cornets than the regulated ones 4. O. de La Marche wrote that the instructions of the Saint-Maximin Decree regarding the typification of flags in the company and their practical use were not followed already in 1474 , who himself was the conductor of company No. 1 during the indicated period:

“Each company has three ranks of infantry, there is a captain, a mounted gendarme and a port-enseigne (i.e. standard bearer) with a guidon; and for every hundred people there is a mounted gendarme-centurion, who carries another, shorter flag-enseigne"

La Marche also noted that the company horse archers were organized into 4 squadrons of 75 people each and had a common guidon. Thus, according to La Marche, the Burgundian company order of 1474 had the following flags: 1 standard of gendarmes, 1 guidon of horse archers, 1 guidon of infantry and 3 anseins (probably cornets bigger size) infantry "hundreds". If we assume that each hundred infantry, according to its administrative division, had 3 cornets of smaller size, not indicated by La Marche, then the number of flags in the company infantry will increase to 12. In this case, the presence of the number “VIIJ” on the cornet of St. Andrew can be explained.

6. Field camp of the Ordinance companies.

A sharp surge in Burgundian military activity, which coincided with the reign of Charles the Bold, forced the Burgundian army to spend a significant amount of time in field camps. In this regard, the importance of tent and marquee services, headed master of tents. Noting the importance of this service and the great responsibility of its chief, O. de La Marche wrote:

“The Duke pays for a good thousand awnings and a thousand pavilions for his companies, for receiving foreign ambassadors, for servants and gendarmes of the Duke’s Hotel; and for each campaign, the master of tents prepares new tents and new pavilions with funds /allocated/ by the prince; the maintenance of the teams, the work and the purchase of fabric alone costs more than thirty thousand livres.”

Temporary housing for field conditions were divided into:

- awnings(tentes) - vertically oriented tents with a round or oval base, with one, less often, two central support poles;

- tentlets(tentelletes) - smaller tents, often with a square or rectangular base;;i>

- pavilions or pavilions(pavillons) - horizontally oriented tents with two or more main support poles.

The variety of names for temporary camp dwellings is reflected in numerous documents of that era. Thus, the accounting sheet of the Lille Arsenal for 1473 lists "renovated old tents and pavilions, 271 purchased square pavilions, 32 tents, a wooden house for the Duke, two pavilions for the Duke of Brittany, a stable for the said Duke"

For the Lorraine campaign of 1475, the Burgundian army was sent “the house of the Duke, for /transportation/ which requires 7 carts, 3 pavilions, an awning for the Duke, 400 pavilions for the ordinance companies and gentlemen of the services of the Duke's Hotel, 350 new stables, 26 awnings with two poles, 7 pieces of awnings for the Duke's stable, 2 awnings for sentries, 16 other tents and pavilions for masters.”

In 1476, they were sent to the Burgundian army camp in La Riviera “600 small tents and pavilions, 100 square pavilions, 2 wooden houses, 130 square tents, 50 square tents, 6 large tents and 6 large square pavilions, and one more wooden house”

The number of people and horses housed in standard army tents and stable tents is easily calculated, thanks to an archival record from 1473: “In addition, the Duke ordered the calculation of 20 pavilions for 100 spears and one / pavilion / for the conducto, the cost of which would be 2,804 florins, and for each company of 100 spears 101 stables, each for 6 horses, which in total for 16 the mouth is 1616 stables, the price of which, at the rate of 20 florins per stable, will be about 32,320 florins.” Based on the prescribed strength of the ordinance company of 900 people (800 combatants and 100 servants), it turns out that 1 pavilion was designed for 45 people.

Judging by the miniatures and engravings of that era (especially worth noting is the series of prints by V. A. Crews “Pavilions and Awnings of the Duke of Burgundy” and miniatures from the “Chronicles” of Schilling and Schodoler, which, taken together, depict precisely the Burgundian field camps), as well as surviving invoices for the work of the Burgundian artist Jean Annekar, the outer layer of tents and marquees could be painted with oil paints or tempera. Most often they depicted the cross of St. Andrew and a flint with tongues of flame. The tents of noble gentlemen could bear images of their coats of arms. Bright pennants made of silk (for the nobility) or linen were mounted on the flagpoles.

The canopies of the tents and tents consisted of individual parts- the roof and the walls laced to it (later the roof and walls were sewn into one whole). The central poles were dug into the ground with their bases and reinforced with guy ropes. Streamers could be placed both inside the tent (this is clearly visible in the engraving by V. A. Crews “Tent”) and outside. Several dozen Burgundian rope bays for the camp structure have been preserved (the Swiss mistakenly took them for ropes for tying prisoners) - in Historical Museum Thun and in the Historical Museum in the Lucerne Town Hall (inv. No. 877). The ropes are woven from hemp threads, their average length is 14 m. The Burgundian army was accompanied during the Lorraine campaign of 1475 “2 other comrades to carry 4 gates for tensioning awnings, 20 carpenters for awnings and pavilions, 200 other awning installers.” During the hike, tents and pavilions were stored in canvas bags.

The Lausanne Ordinance (1476) prescribed the procedure for setting up a field camp and its internal structure. Obviously, Charles the Bold created this decree, being under the impression of ancient descriptions of the field camp of the Roman army:

“The quartermaster is responsible for the quartering of the army in the following order:

Each of the parts of the camp assigned to one of the army corps should first of all be divided into two separate quarters for the two battle lines, each of these quarters should be divided into three parts, the first two for the companies and the third for the infantry of each battle line. In addition, the conductor must place separately the gendarmes and separately the archers of his company, distributed among squadrons and cells. Infantrymen must also live in hundreds, divided into quarts of 25 people

For each top commander, housing will be arranged in the center of his army corps, captains will be stationed in the center of their battle lines, company commanders in the center of their companies, squadron commanders in the center of their squadrons, and cell commanders in the center of their squads."