The sign of the trigonometric function depends solely on the coordinate quarter in which the numeric argument is located. Last time we learned how to translate arguments from a radian measure into a degree measure (see the lesson “ Radian and degree measure of an angle”), and then determine this same coordinate quarter. Now let's deal, in fact, with the definition of the sign of the sine, cosine and tangent.

The sine of the angle α is the ordinate (coordinate y) of a point on a trigonometric circle, which occurs when the radius is rotated through the angle α.

The cosine of the angle α is the abscissa (x coordinate) of a point on a trigonometric circle, which occurs when the radius rotates through the angle α.

The tangent of the angle α is the ratio of the sine to the cosine. Or, equivalently, the ratio of the y-coordinate to the x-coordinate.

Notation: sin α = y ; cosα = x; tgα = y : x .

All these definitions are familiar to you from the high school algebra course. However, we are not interested in the definitions themselves, but in the consequences that arise on the trigonometric circle. Take a look:

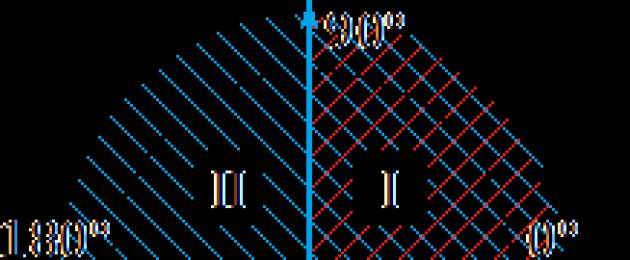

The blue color indicates the positive direction of the OY axis (ordinate axis), the red color indicates the positive direction of the OX axis (abscissa axis). On this "radar" the signs of trigonometric functions become obvious. In particular:

- sin α > 0 if the angle α lies in the I or II coordinate quarter. This is because, by definition, a sine is an ordinate (y coordinate). And the y coordinate will be positive precisely in the I and II coordinate quarters;

- cos α > 0 if the angle α lies in the I or IV coordinate quarter. Because only there the x coordinate (it is also the abscissa) will be greater than zero;

- tg α > 0 if the angle α lies in the I or III coordinate quadrant. This follows from the definition: after all, tg α = y : x , so it is positive only where the signs of x and y coincide. This happens in the 1st coordinate quarter (here x > 0, y > 0) and the 3rd coordinate quarter (x< 0, y < 0).

For clarity, we note the signs of each trigonometric function - sine, cosine and tangent - on separate "radar". We get the following picture:

Note: in my reasoning, I never spoke about the fourth trigonometric function - the cotangent. The fact is that the signs of the cotangent coincide with the signs of the tangent - there are no special rules there.

Now I propose to consider examples similar to tasks B11 from the trial exam in mathematics, which took place on September 27, 2011. After all, the best way to understand the theory is practice. Preferably a lot of practice. Of course, the conditions of the tasks were slightly changed.

A task. Determine the signs of trigonometric functions and expressions (the values of the functions themselves do not need to be considered):

- sin(3π/4);

- cos(7π/6);

- tan (5π/3);

- sin(3π/4) cos(5π/6);

- cos (2π/3) tg (π/4);

- sin(5π/6) cos(7π/4);

- tan (3π/4) cos (5π/3);

- ctg (4π/3) tg (π/6).

The action plan is as follows: first, we convert all angles from radian measure to degree measure (π → 180°), and then look in which coordinate quarter the resulting number lies. Knowing the quarters, we can easily find the signs - according to the rules just described. We have:

- sin (3π/4) = sin (3 180°/4) = sin 135°. Since 135° ∈ , this is an angle from the II coordinate quadrant. But the sine in the second quarter is positive, so sin (3π/4) > 0;

- cos (7π/6) = cos (7 180°/6) = cos 210°. Because 210° ∈ , this is an angle from the III coordinate quadrant in which all cosines are negative. Therefore, cos (7π/6)< 0;

- tg (5π/3) = tg (5 180°/3) = tg 300°. Since 300° ∈ , we are in quadrant IV, where the tangent takes negative values. Therefore tg (5π/3)< 0;

- sin (3π/4) cos (5π/6) = sin (3 180°/4) cos (5 180°/6) = sin 135° cos 150°. Let's deal with the sine: because 135° ∈ , this is the second quarter, in which the sines are positive, i.e. sin (3π/4) > 0. Now we work with the cosine: 150° ∈ - again the second quarter, the cosines there are negative. Therefore cos (5π/6)< 0. Наконец, следуя правилу «плюс на минус дает знак минус», получаем: sin (3π/4) · cos (5π/6) < 0;

- cos (2π/3) tg (π/4) = cos (2 180°/3) tg (180°/4) = cos 120° tg 45°. We look at the cosine: 120° ∈ is the II coordinate quarter, so cos (2π/3)< 0. Смотрим на тангенс: 45° ∈ — это I четверть (самый обычный угол в тригонометрии). Тангенс там положителен, поэтому tg (π/4) >0. Again we got a product in which factors of different signs. Since “a minus times a plus gives a minus”, we have: cos (2π/3) tg (π/4)< 0;

- sin (5π/6) cos (7π/4) = sin (5 180°/6) cos (7 180°/4) = sin 150° cos 315°. We work with the sine: since 150° ∈ , we are talking about the II coordinate quarter, where the sines are positive. Therefore, sin (5π/6) > 0. Similarly, 315° ∈ is the IV coordinate quarter, the cosines there are positive. Therefore, cos (7π/4) > 0. We got the product of two positive numbers - such an expression is always positive. We conclude: sin (5π/6) cos (7π/4) > 0;

- tg (3π/4) cos (5π/3) = tg (3 180°/4) cos (5 180°/3) = tg 135° cos 300°. But the angle 135° ∈ is the second quarter, i.e. tan (3π/4)< 0. Аналогично, угол 300° ∈ — это IV четверть, т.е. cos (5π/3) >0. Since “a minus plus gives a minus sign”, we have: tg (3π/4) cos (5π/3)< 0;

- ctg (4π/3) tg (π/6) = ctg (4 180°/3) tg (180°/6) = ctg 240° tg 30°. We look at the cotangent argument: 240° ∈ is the III coordinate quarter, therefore ctg (4π/3) > 0. Similarly, for the tangent we have: 30° ∈ is the I coordinate quarter, i.e. easiest corner. Therefore, tg (π/6) > 0. Again, we got two positive expressions - their product will also be positive. Therefore ctg (4π/3) tg (π/6) > 0.

Finally, let's look at a few more complex problems. In addition to finding out the sign of the trigonometric function, here you have to do a little calculation - just like it is done in real problems B11. In principle, these are almost real tasks that are really found in the exam in mathematics.

A task. Find sin α if sin 2 α = 0.64 and α ∈ [π/2; π].

Since sin 2 α = 0.64, we have: sin α = ±0.8. It remains to decide: plus or minus? By assumption, the angle α ∈ [π/2; π] is the II coordinate quarter, where all sines are positive. Therefore, sin α = 0.8 - the uncertainty with signs is eliminated.

A task. Find cos α if cos 2 α = 0.04 and α ∈ [π; 3π/2].

We act similarly, i.e. we take the square root: cos 2 α = 0.04 ⇒ cos α = ±0.2. By assumption, the angle α ∈ [π; 3π/2], i.e. we are talking about the III coordinate quarter. There, all cosines are negative, so cos α = −0.2.

A task. Find sin α if sin 2 α = 0.25 and α ∈ .

We have: sin 2 α = 0.25 ⇒ sin α = ±0.5. Again we look at the angle: α ∈ is the IV coordinate quarter, in which, as you know, the sine will be negative. Thus, we conclude: sin α = −0.5.

A task. Find tg α if tg 2 α = 9 and α ∈ .

Everything is the same, only for the tangent. We take the square root: tg 2 α = 9 ⇒ tg α = ±3. But by the condition, the angle α ∈ is the I coordinate quadrant. All trigonometric functions, incl. tangent, there are positive, so tg α = 3. That's it!

Coordinates x points lying on the circle are equal to cos(θ), and the coordinates y correspond to sin(θ), where θ is the magnitude of the angle.

- If you find it difficult to remember this rule, just remember that in the pair (cos; sin) "the sine comes last".

- This rule can be deduced if we consider right triangles and the definition of these trigonometric functions (the sine of the angle is equal to the ratio of the length of the opposite, and the cosine of the adjacent leg to the hypotenuse).

Write down the coordinates of four points on the circle. A "unit circle" is a circle whose radius is equal to one. Use this to determine the coordinates x and y at four points of intersection of the coordinate axes with the circle. Above, for clarity, we have designated these points as "east", "north", "west" and "south", although they do not have established names.

- "East" corresponds to a point with coordinates (1; 0) .

- "North" corresponds to a point with coordinates (0; 1) .

- "West" corresponds to a point with coordinates (-1; 0) .

- "South" corresponds to a point with coordinates (0; -1) .

- This is similar to a normal graph, so there is no need to memorize these values, it is enough to remember the basic principle.

Remember the coordinates of the points in the first quadrant. The first quadrant is located in the upper right part of the circle, where the coordinates x and y take positive values. These are the only coordinates you need to remember:

Draw straight lines and determine the coordinates of the points of their intersection with the circle. If you draw straight horizontal and vertical lines from the points of one quadrant, the second points of intersection of these lines with the circle will have coordinates x and y with the same absolute values but different signs. In other words, you can draw horizontal and vertical lines from the points of the first quadrant and sign the intersection points with the circle with the same coordinates, but at the same time leave room for the correct sign ("+" or "-") on the left.

Use symmetry rules to determine the sign of coordinates. There are several ways to determine where to put the "-" sign:

- remember the basic rules for regular charts. Axis x negative on the left and positive on the right. Axis y negative from below and positive from above;

- start from the first quadrant and draw lines to other points. If the line crosses the axis y, coordinate x will change its sign. If the line crosses the axis x, the sign of the coordinate will change y;

- remember that in the first quadrant all functions are positive, in the second quadrant only the sine is positive, in the third quadrant only the tangent is positive, and in the fourth quadrant only the cosine is positive;

- whichever method you use, the first quadrant should be (+,+), the second (-,+), the third (-,-) and the fourth (+,-).

Check if you made a mistake. Below is a complete list of coordinates of "special" points (except for four points on the coordinate axes), if you move counterclockwise along the unit circle. Remember that to determine all these values, it is enough to remember the coordinates of the points only in the first quadrant:

- first quadrant :( 3 2 , 1 2 (\displaystyle (\frac (\sqrt (3))(2)),(\frac (1)(2)))); (2 2 , 2 2 (\displaystyle (\frac (\sqrt (2))(2)),(\frac (\sqrt (2))(2)))); (1 2 , 3 2 (\displaystyle (\frac (1)(2)),(\frac (\sqrt (3))(2))));

- second quadrant :( − 1 2 , 3 2 (\displaystyle -(\frac (1)(2)),(\frac (\sqrt (3))(2)))); (− 2 2 , 2 2 (\displaystyle -(\frac (\sqrt (2))(2)),(\frac (\sqrt (2))(2)))); (− 3 2 , 1 2 (\displaystyle -(\frac (\sqrt (3))(2)),(\frac (1)(2))));

- third quadrant :( − 3 2 , − 1 2 (\displaystyle -(\frac (\sqrt (3))(2)),-(\frac (1)(2)))); (− 2 2 , − 2 2 (\displaystyle -(\frac (\sqrt (2))(2)),-(\frac (\sqrt (2))(2)))); (− 1 2 , − 3 2 (\displaystyle -(\frac (1)(2)),-(\frac (\sqrt (3))(2))));

- fourth quadrant :( 1 2 , − 3 2 (\displaystyle (\frac (1)(2)),-(\frac (\sqrt (3))(2)))); (2 2 , − 2 2 (\displaystyle (\frac (\sqrt (2))(2)),-(\frac (\sqrt (2))(2)))); (3 2 , − 1 2 (\displaystyle (\frac (\sqrt (3))(2)),-(\frac (1)(2)))).

Simply put, these are vegetables cooked in water according to a special recipe. I will consider two initial components (vegetable salad and water) and the finished result - borscht. Geometrically, this can be represented as a rectangle in which one side denotes lettuce, the other side denotes water. The sum of these two sides will denote borscht. The diagonal and area of such a "borscht" rectangle are purely mathematical concepts and are never used in borscht recipes.

How do lettuce and water turn into borscht in terms of mathematics? How can the sum of two segments turn into trigonometry? To understand this, we need linear angle functions.

You won't find anything about linear angle functions in math textbooks. But without them there can be no mathematics. The laws of mathematics, like the laws of nature, work whether we know they exist or not.

Linear angular functions are the laws of addition. See how algebra turns into geometry and geometry turns into trigonometry.

Is it possible to do without linear angular functions? You can, because mathematicians still manage without them. The trick of mathematicians lies in the fact that they always tell us only about those problems that they themselves can solve, and never tell us about those problems that they cannot solve. See. If we know the result of the addition and one term, we use subtraction to find the other term. Everything. We do not know other problems and we are not able to solve them. What to do if we know only the result of the addition and do not know both terms? In this case, the result of addition must be decomposed into two terms using linear angular functions. Further, we ourselves choose what one term can be, and the linear angular functions show what the second term should be in order for the result of the addition to be exactly what we need. There can be an infinite number of such pairs of terms. In everyday life, we do very well without decomposing the sum; subtraction is enough for us. But in scientific studies of the laws of nature, the expansion of the sum into terms can be very useful.

Another law of addition that mathematicians don't like to talk about (another trick of theirs) requires the terms to have the same unit of measure. For lettuce, water, and borscht, these may be units of weight, volume, cost, or unit of measure.

The figure shows two levels of difference for math. The first level is the differences in the field of numbers, which are indicated a, b, c. This is what mathematicians do. The second level is the differences in the area of units of measurement, which are shown in square brackets and are indicated by the letter U. This is what physicists do. We can understand the third level - the differences in the scope of the described objects. Different objects can have the same number of the same units of measure. How important this is, we can see on the example of borscht trigonometry. If we add subscripts to the same notation for the units of measurement of different objects, we can say exactly what mathematical quantity describes a particular object and how it changes over time or in connection with our actions. letter W I will mark the water with the letter S I will mark the salad with the letter B- borsch. Here's what the linear angle functions for borscht would look like.

If we take some part of the water and some part of the salad, together they will turn into one serving of borscht. Here I suggest you take a little break from borscht and remember your distant childhood. Remember how we were taught to put bunnies and ducks together? It was necessary to find how many animals will turn out. What then were we taught to do? We were taught to separate units from numbers and add numbers. Yes, any number can be added to any other number. This is a direct path to the autism of modern mathematics - we do not understand what, it is not clear why, and we understand very poorly how this relates to reality, because of the three levels of difference, mathematicians operate on only one. It will be more correct to learn how to move from one unit of measurement to another.

And bunnies, and ducks, and little animals can be counted in pieces. One common unit of measurement for different objects allows us to add them together. This is a children's version of the problem. Let's look at a similar problem for adults. What do you get when you add bunnies and money? There are two possible solutions here.

First option. We determine the market value of the bunnies and add it to the available cash. We got the total value of our wealth in terms of money.

Second option. You can add the number of bunnies to the number of banknotes we have. We will get the amount of movable property in pieces.

As you can see, the same addition law allows you to get different results. It all depends on what exactly we want to know.

But back to our borscht. Now we can see what will happen for different values of the angle of the linear angle functions.

The angle is zero. We have salad but no water. We can't cook borscht. The amount of borscht is also zero. This does not mean at all that zero borscht is equal to zero water. Zero borsch can also be at zero salad (right angle).

For me personally, this is the main mathematical proof of the fact that . Zero does not change the number when added. This is because addition itself is impossible if there is only one term and the second term is missing. You can relate to this as you like, but remember - all mathematical operations with zero were invented by mathematicians themselves, so discard your logic and stupidly cram the definitions invented by mathematicians: "division by zero is impossible", "any number multiplied by zero equals zero" , "behind the point zero" and other nonsense. It is enough to remember once that zero is not a number, and you will never have a question whether zero is a natural number or not, because such a question generally loses all meaning: how can one consider a number that which is not a number. It's like asking what color to attribute an invisible color to. Adding zero to a number is like painting with paint that doesn't exist. They waved a dry brush and tell everyone that "we have painted." But I digress a little.

The angle is greater than zero but less than forty-five degrees. We have a lot of lettuce, but little water. As a result, we get a thick borscht.

The angle is forty-five degrees. We have equal amounts of water and lettuce. This is the perfect borscht (may the cooks forgive me, it's just math).

The angle is greater than forty-five degrees but less than ninety degrees. We have a lot of water and little lettuce. Get liquid borscht.

Right angle. We have water. Only memories remain of the lettuce, as we continue to measure the angle from the line that once marked the lettuce. We can't cook borscht. The amount of borscht is zero. In that case, hold on and drink water while it's available)))

Here. Something like this. I can tell other stories here that will be more than appropriate here.

The two friends had their shares in the common business. After the murder of one of them, everything went to the other.

The emergence of mathematics on our planet.

All these stories are told in the language of mathematics using linear angular functions. Some other time I will show you the real place of these functions in the structure of mathematics. In the meantime, let's return to the trigonometry of borscht and consider projections.

Saturday, October 26, 2019

I watched an interesting video about Grandi's row One minus one plus one minus one - Numberphile. Mathematicians lie. They did not perform an equality test in their reasoning.

This resonates with my reasoning about .

Let's take a closer look at the signs that mathematicians are cheating us. At the very beginning of the reasoning, mathematicians say that the sum of the sequence DEPENDS on whether the number of elements in it is even or not. This is an OBJECTIVELY ESTABLISHED FACT. What happens next?

Next, mathematicians subtract the sequence from unity. What does this lead to? This leads to a change in the number of elements in the sequence - an even number changes to an odd number, an odd number changes to an even number. After all, we have added one element equal to one to the sequence. Despite all the external similarity, the sequence before the transformation is not equal to the sequence after the transformation. Even if we are talking about an infinite sequence, we must remember that an infinite sequence with an odd number of elements is not equal to an infinite sequence with an even number of elements.

Putting an equal sign between two sequences different in the number of elements, mathematicians claim that the sum of the sequence DOES NOT DEPEND on the number of elements in the sequence, which contradicts an OBJECTIVELY ESTABLISHED FACT. Further reasoning about the sum of an infinite sequence is false, because it is based on a false equality.

If you see that mathematicians place brackets in the course of proofs, rearrange the elements of a mathematical expression, add or remove something, be very careful, most likely they are trying to deceive you. Like card conjurers, mathematicians divert your attention with various manipulations of the expression in order to eventually give you a false result. If you can’t repeat the card trick without knowing the secret of cheating, then in mathematics everything is much simpler: you don’t even suspect anything about cheating, but repeating all the manipulations with a mathematical expression allows you to convince others of the correctness of the result, just like when have convinced you.

Question from the audience: And infinity (as the number of elements in the sequence S), is it even or odd? How can you change the parity of something that has no parity?

Infinity for mathematicians is like the Kingdom of Heaven for priests - no one has ever been there, but everyone knows exactly how everything works there))) I agree, after death you will be absolutely indifferent whether you lived an even or odd number of days, but ... Adding just one day at the beginning of your life, we will get a completely different person: his last name, first name and patronymic are exactly the same, only the date of birth is completely different - he was born one day before you.

And now to the point))) Suppose a finite sequence that has parity loses this parity when going to infinity. Then any finite segment of an infinite sequence must also lose parity. We do not observe this. The fact that we cannot say for sure whether the number of elements in an infinite sequence is even or odd does not mean at all that the parity has disappeared. Parity, if it exists, cannot disappear into infinity without a trace, as in the sleeve of a card sharper. There is a very good analogy for this case.

Have you ever asked a cuckoo sitting in a clock in which direction the clock hand rotates? For her, the arrow rotates in the opposite direction to what we call "clockwise". It may sound paradoxical, but the direction of rotation depends solely on which side we observe the rotation from. And so, we have one wheel that rotates. We cannot say in which direction the rotation occurs, since we can observe it both from one side of the plane of rotation and from the other. We can only testify to the fact that there is rotation. Complete analogy with the parity of an infinite sequence S.

Now let's add a second rotating wheel, the plane of rotation of which is parallel to the plane of rotation of the first rotating wheel. We still can't tell exactly which direction these wheels are spinning, but we can tell with absolute certainty whether both wheels are spinning in the same direction or in opposite directions. Comparing two infinite sequences S and 1-S, I showed with the help of mathematics that these sequences have different parity and putting an equal sign between them is a mistake. Personally, I believe in mathematics, I do not trust mathematicians))) By the way, in order to fully understand the geometry of transformations of infinite sequences, it is necessary to introduce the concept "simultaneity". This will need to be drawn.

Wednesday, August 7, 2019

Concluding the conversation about , we need to consider an infinite set. Gave in that the concept of "infinity" acts on mathematicians, like a boa constrictor on a rabbit. The quivering horror of infinity deprives mathematicians of common sense. Here is an example:

The original source is located. Alpha denotes a real number. The equal sign in the above expressions indicates that if you add a number or infinity to infinity, nothing will change, the result will be the same infinity. If we take an infinite set of natural numbers as an example, then the considered examples can be represented as follows:

To visually prove their case, mathematicians have come up with many different methods. Personally, I look at all these methods as the dances of shamans with tambourines. In essence, they all come down to the fact that either some of the rooms are not occupied and new guests are settled in them, or that some of the visitors are thrown out into the corridor to make room for the guests (very humanly). I presented my view on such decisions in the form of a fantastic story about the Blonde. What is my reasoning based on? Moving an infinite number of visitors takes an infinite amount of time. After we have vacated the first guest room, one of the visitors will always walk along the corridor from his room to the next one until the end of time. Of course, the time factor can be stupidly ignored, but this will already be from the category of "the law is not written for fools." It all depends on what we are doing: adjusting reality to mathematical theories or vice versa.

What is an "infinite hotel"? An infinity inn is an inn that always has any number of vacancies, no matter how many rooms are occupied. If all the rooms in the endless hallway "for visitors" are occupied, there is another endless hallway with rooms for "guests". There will be an infinite number of such corridors. At the same time, the "infinite hotel" has an infinite number of floors in an infinite number of buildings on an infinite number of planets in an infinite number of universes created by an infinite number of Gods. Mathematicians, on the other hand, are not able to move away from banal everyday problems: God-Allah-Buddha is always only one, the hotel is one, the corridor is only one. So mathematicians are trying to juggle the serial numbers of hotel rooms, convincing us that it is possible to "shove the unpushed".

I will demonstrate the logic of my reasoning to you using the example of an infinite set of natural numbers. First you need to answer a very simple question: how many sets of natural numbers exist - one or many? There is no correct answer to this question, since we ourselves invented numbers, there are no numbers in Nature. Yes, Nature knows how to count perfectly, but for this she uses other mathematical tools that are not familiar to us. As Nature thinks, I will tell you another time. Since we invented the numbers, we ourselves will decide how many sets of natural numbers exist. Consider both options, as befits a real scientist.

Option one. "Let us be given" a single set of natural numbers, which lies serenely on a shelf. We take this set from the shelf. That's it, there are no other natural numbers left on the shelf and there is nowhere to take them. We cannot add one to this set, since we already have it. What if you really want to? No problem. We can take a unit from the set we have already taken and return it to the shelf. After that, we can take a unit from the shelf and add it to what we have left. As a result, we again get an infinite set of natural numbers. You can write all our manipulations like this:

I have written down the operations in algebraic notation and in set theory notation, listing the elements of the set in detail. The subscript indicates that we have one and only set of natural numbers. It turns out that the set of natural numbers will remain unchanged only if one is subtracted from it and the same one is added.

Option two. We have many different infinite sets of natural numbers on the shelf. I emphasize - DIFFERENT, despite the fact that they are practically indistinguishable. We take one of these sets. Then we take one from another set of natural numbers and add it to the set we have already taken. We can even add two sets of natural numbers. Here's what we get:

The subscripts "one" and "two" indicate that these elements belonged to different sets. Yes, if you add one to an infinite set, the result will also be an infinite set, but it will not be the same as the original set. If another infinite set is added to one infinite set, the result is a new infinite set consisting of the elements of the first two sets.

The set of natural numbers is used for counting in the same way as a ruler for measurements. Now imagine that you have added one centimeter to the ruler. This will already be a different line, not equal to the original.

You can accept or not accept my reasoning - this is your own business. But if you ever run into mathematical problems, consider whether you are on the path of false reasoning, trodden by generations of mathematicians. After all, mathematics classes, first of all, form a stable stereotype of thinking in us, and only then they add mental abilities to us (or vice versa, they deprive us of free thinking).

pozg.ru

Sunday, August 4, 2019

I was writing a postscript to an article about and saw this wonderful text on Wikipedia:

We read: "... the rich theoretical basis of Babylonian mathematics did not have a holistic character and was reduced to a set of disparate techniques, devoid of a common system and evidence base."

Wow! How smart we are and how well we can see the shortcomings of others. Is it weak for us to look at modern mathematics in the same context? Slightly paraphrasing the above text, personally I got the following:

The rich theoretical basis of modern mathematics does not have a holistic character and is reduced to a set of disparate sections, devoid of a common system and evidence base.

I will not go far to confirm my words - it has a language and conventions that are different from the language and conventions of many other branches of mathematics. The same names in different branches of mathematics can have different meanings. I want to devote a whole cycle of publications to the most obvious blunders of modern mathematics. See you soon.

Saturday, August 3, 2019

How to divide a set into subsets? To do this, you must enter a new unit of measure, which is present in some of the elements of the selected set. Consider an example.

May we have many BUT consisting of four people. This set is formed on the basis of "people" Let's designate the elements of this set through the letter a, the subscript with a number will indicate the ordinal number of each person in this set. Let's introduce a new unit of measurement "sexual characteristic" and denote it by the letter b. Since sexual characteristics are inherent in all people, we multiply each element of the set BUT on gender b. Notice that our "people" set has now become the "people with gender" set. After that, we can divide the sexual characteristics into male bm and women's bw gender characteristics. Now we can apply a mathematical filter: we select one of these sexual characteristics, it does not matter which one is male or female. If it is present in a person, then we multiply it by one, if there is no such sign, we multiply it by zero. And then we apply the usual school mathematics. See what happened.

After multiplication, reductions and rearrangements, we got two subsets: the male subset bm and a subset of women bw. Approximately the same way mathematicians reason when they apply set theory in practice. But they do not let us in on the details, but give us the finished result - "a lot of people consists of a subset of men and a subset of women." Naturally, you may have a question, how correctly applied mathematics in the above transformations? I dare to assure you that in fact the transformations are done correctly, it is enough to know the mathematical justification of arithmetic, Boolean algebra and other sections of mathematics. What it is? Some other time I will tell you about it.

As for supersets, it is possible to combine two sets into one superset by choosing a unit of measurement that is present in the elements of these two sets.

As you can see, units of measurement and common math make set theory a thing of the past. A sign that all is not well with set theory is that mathematicians have come up with their own language and notation for set theory. The mathematicians did what the shamans once did. Only shamans know how to "correctly" apply their "knowledge". This "knowledge" they teach us.

In conclusion, I want to show you how mathematicians manipulate

Let's say Achilles runs ten times faster than the tortoise and is a thousand paces behind it. In the time it takes Achilles to run this distance, the tortoise will crawl a hundred steps in the same direction. When Achilles has run a hundred steps, the tortoise will crawl another ten steps, and so on. The process will continue indefinitely, Achilles will never catch up with the tortoise.

This reasoning became a logical shock for all subsequent generations. Aristotle, Diogenes, Kant, Hegel, Gilbert... All of them, in one way or another, considered Zeno's aporias. The shock was so strong that " ... discussions continue at the present time, the scientific community has not yet managed to come to a common opinion about the essence of paradoxes ... mathematical analysis, set theory, new physical and philosophical approaches were involved in the study of the issue; none of them became a universally accepted solution to the problem ..."[Wikipedia," Zeno's Aporias "]. Everyone understands that they are being fooled, but no one understands what the deception is.

From the point of view of mathematics, Zeno in his aporia clearly demonstrated the transition from the value to. This transition implies applying instead of constants. As far as I understand, the mathematical apparatus for applying variable units of measurement has either not yet been developed, or it has not been applied to Zeno's aporia. The application of our usual logic leads us into a trap. We, by the inertia of thinking, apply constant units of time to the reciprocal. From a physical point of view, it looks like time slowing down to a complete stop at the moment when Achilles catches up with the tortoise. If time stops, Achilles can no longer overtake the tortoise.

If we turn the logic we are used to, everything falls into place. Achilles runs at a constant speed. Each subsequent segment of its path is ten times shorter than the previous one. Accordingly, the time spent on overcoming it is ten times less than the previous one. If we apply the concept of "infinity" in this situation, then it would be correct to say "Achilles will infinitely quickly overtake the tortoise."

How to avoid this logical trap? Remain in constant units of time and do not switch to reciprocal values. In Zeno's language, it looks like this:

In the time it takes Achilles to run a thousand steps, the tortoise crawls a hundred steps in the same direction. During the next time interval, equal to the first, Achilles will run another thousand steps, and the tortoise will crawl one hundred steps. Now Achilles is eight hundred paces ahead of the tortoise.

This approach adequately describes reality without any logical paradoxes. But this is not a complete solution to the problem. Einstein's statement about the insurmountability of the speed of light is very similar to Zeno's aporia "Achilles and the tortoise". We have yet to study, rethink and solve this problem. And the solution must be sought not in infinitely large numbers, but in units of measurement.

Another interesting aporia of Zeno tells of a flying arrow:

A flying arrow is motionless, since at each moment of time it is at rest, and since it is at rest at every moment of time, it is always at rest.

In this aporia, the logical paradox is overcome very simply - it is enough to clarify that at each moment of time the flying arrow is at rest at different points in space, which, in fact, is movement. There is another point to be noted here. From one photograph of a car on the road, it is impossible to determine either the fact of its movement or the distance to it. To determine the fact of the movement of the car, two photographs taken from the same point at different points in time are needed, but they cannot be used to determine the distance. To determine the distance to the car, you need two photographs taken from different points in space at the same time, but you cannot determine the fact of movement from them (naturally, you still need additional data for calculations, trigonometry will help you). What I want to point out in particular is that two points in time and two points in space are two different things that should not be confused as they provide different opportunities for exploration.

I will show the process with an example. We select "red solid in a pimple" - this is our "whole". At the same time, we see that these things are with a bow, and there are without a bow. After that, we select a part of the "whole" and form a set "with a bow". This is how shamans feed themselves by tying their set theory to reality.

Now let's do a little trick. Let's take "solid in a pimple with a bow" and unite these "whole" by color, selecting red elements. We got a lot of "red". Now a tricky question: are the received sets "with a bow" and "red" the same set or two different sets? Only shamans know the answer. More precisely, they themselves do not know anything, but as they say, so be it.

This simple example shows that set theory is completely useless when it comes to reality. What's the secret? We formed a set of "red solid pimply with a bow". The formation took place according to four different units of measurement: color (red), strength (solid), roughness (in a bump), decorations (with a bow). Only a set of units of measurement makes it possible to adequately describe real objects in the language of mathematics. Here's what it looks like.

The letter "a" with different indices denotes different units of measurement. In parentheses, units of measurement are highlighted, according to which the "whole" is allocated at the preliminary stage. The unit of measurement, according to which the set is formed, is taken out of brackets. The last line shows the final result - an element of the set. As you can see, if we use units to form a set, then the result does not depend on the order of our actions. And this is mathematics, and not the dances of shamans with tambourines. Shamans can “intuitively” come to the same result, arguing it with “obviousness”, because units of measurement are not included in their “scientific” arsenal.

With the help of units of measurement, it is very easy to break one or combine several sets into one superset. Let's take a closer look at the algebra of this process.

This article has collected tables of sines, cosines, tangents and cotangents. First, we give a table of basic values of trigonometric functions, that is, a table of sines, cosines, tangents and cotangents of angles 0, 30, 45, 60, 90, ..., 360 degrees ( 0, π/6, π/4, π/3, π/2, …, 2π radian). After that, we will give a table of sines and cosines, as well as a table of tangents and cotangents by V. M. Bradis, and show how to use these tables when finding the values of trigonometric functions.

Page navigation.

Table of sines, cosines, tangents and cotangents for angles 0, 30, 45, 60, 90, ... degrees

Bibliography.

- Algebra: Proc. for 9 cells. avg. school / Yu. N. Makarychev, N. G. Mindyuk, K. I. Neshkov, S. B. Suvorova; Ed. S. A. Telyakovsky.- M.: Enlightenment, 1990.- 272 p.: Ill.- ISBN 5-09-002727-7

- Bashmakov M.I. Algebra and the beginning of analysis: Proc. for 10-11 cells. avg. school - 3rd ed. - M.: Enlightenment, 1993. - 351 p.: ill. - ISBN 5-09-004617-4.

- Algebra and the beginning of the analysis: Proc. for 10-11 cells. general education institutions / A. N. Kolmogorov, A. M. Abramov, Yu. P. Dudnitsyn and others; Ed. A. N. Kolmogorova.- 14th ed.- M.: Enlightenment, 2004.- 384 p.: ill.- ISBN 5-09-013651-3.

- Gusev V. A., Mordkovich A. G. Mathematics (a manual for applicants to technical schools): Proc. allowance.- M.; Higher school, 1984.-351 p., ill.

- Bradis V. M. Four-digit mathematical tables: For general education. textbook establishments. - 2nd ed. - M.: Bustard, 1999.- 96 p.: ill. ISBN 5-7107-2667-2

Counting angles on a trigonometric circle.

Attention!

There are additional

material in Special Section 555.

For those who strongly "not very..."

And for those who "very much...")

It is almost the same as in the previous lesson. There are axes, a circle, an angle, everything is chin-china. Added numbers of quarters (in the corners of a large square) - from the first to the fourth. And then suddenly who does not know? As you can see, the quarters (they are also called the beautiful word "quadrants") are numbered counterclockwise. Added angle values on axes. Everything is clear, no frills.

And added a green arrow. With a plus. What does she mean? Let me remind you that the fixed side of the corner always nailed to the positive axis OH. So, if we twist the moving side of the corner plus arrow, i.e. in ascending quarter numbers, the angle will be considered positive. For example, the picture shows a positive angle of +60°.

If we postpone the corners in the opposite direction, clockwise, angle will be considered negative. Hover over the picture (or touch the picture on the tablet), you will see a blue arrow with a minus. This is the direction of the negative reading of the angles. A negative angle (-60°) is shown as an example. And you will also see how the numbers on the axes have changed ... I also translated them into negative angles. The numbering of the quadrants does not change.

Here, usually, the first misunderstandings begin. How so!? And if the negative angle on the circle coincides with the positive!? And in general, it turns out that the same position of the movable side (or a point on the numerical circle) can be called both a negative angle and a positive one!?

Yes. Exactly. Let's say a positive angle of 90 degrees takes on a circle exactly the same position as a negative angle of minus 270 degrees. A positive angle, for example +110° degrees, takes exactly the same position as the negative angle is -250°.

No problem. Everything is correct.) The choice of a positive or negative calculation of the angle depends on the condition of the assignment. If the condition says nothing plain text about the sign of the angle, (like "determine the smallest positive angle", etc.), then we work with values that are convenient for us.

An exception (and how without them ?!) are trigonometric inequalities, but there we will master this trick.

And now a question for you. How do I know that the position of the 110° angle is the same as the position of the -250° angle?

I will hint that this is due to the full turnover. In 360°... Not clear? Then we draw a circle. We draw on paper. Marking the corner about 110°. And believe how much remains until a full turn. Just 250° remains...

Got it? And now - attention! If the angles 110° and -250° occupy the circle same

position, then what? Yes, the fact that the angles are 110 ° and -250 ° exactly the same

sine, cosine, tangent and cotangent!

Those. sin110° = sin(-250°), ctg110° = ctg(-250°) and so on. Now this is really important! And in itself - there are a lot of tasks where it is necessary to simplify expressions, and as a basis for the subsequent development of reduction formulas and other intricacies of trigonometry.

Of course, I took 110 ° and -250 ° at random, purely for example. All these equalities work for any angles occupying the same position on the circle. 60° and -300°, -75° and 285°, and so on. I note right away that the corners in these couples - various. But they have trigonometric functions - the same.

I think you understand what negative angles are. It's quite simple. Counter-clockwise is a positive count. Along the way, it's negative. Consider angle positive or negative depends on us. From our desire. Well, and more from the task, of course ... I hope you understand how to move in trigonometric functions from negative to positive angles and vice versa. Draw a circle, an approximate angle, and see how much is missing before a full turn, i.e. up to 360°.

Angles greater than 360°.

Let's deal with angles that are greater than 360 °. And such things happen? There are, of course. How to draw them on a circle? Not a problem! Suppose we need to understand in which quarter an angle of 1000 ° will fall? Easily! We make one full turn counterclockwise (the angle was given to us positive!). Rewind 360°. Well, let's move on! Another turn - it has already turned out 720 °. How much is left? 280°. It is not enough for a full turn ... But the angle is more than 270 ° - and this is the border between the third and fourth quarter. So our angle of 1000° falls into the fourth quarter. Everything.

As you can see, it's quite simple. Let me remind you once again that the angle of 1000° and the angle of 280°, which we obtained by discarding the "extra" full turns, are, strictly speaking, various corners. But the trigonometric functions of these angles exactly the same! Those. sin1000° = sin280°, cos1000° = cos280° etc. If I were a sine, I wouldn't notice the difference between these two angles...

Why is all this necessary? Why do we need to translate angles from one to another? Yes, all for the same.) In order to simplify expressions. Simplification of expressions, in fact, is the main task of school mathematics. Well, along the way, the head is training.)

Well, shall we practice?)

We answer questions. Simple at first.

1. In which quarter does the angle -325° fall?

2. In which quarter does the angle 3000° fall?

3. In which quarter does the angle -3000° fall?

There is a problem? Or insecurity? We go to Section 555, Practical work with a trigonometric circle. There, in the first lesson of this very "Practical work ..." everything is detailed ... In such questions of uncertainty shouldn't!

4. What is the sign of sin555°?

5. What is the sign of tg555°?

Determined? Excellent! Doubt? It is necessary to Section 555 ... By the way, there you will learn how to draw tangent and cotangent on a trigonometric circle. A very useful thing.

And now the smarter questions.

6. Bring the expression sin777° to the sine of the smallest positive angle.

7. Bring the expression cos777° to the cosine of the largest negative angle.

8. Convert the expression cos(-777°) to the cosine of the smallest positive angle.

9. Bring the expression sin777° to the sine of the largest negative angle.

What, questions 6-9 puzzled? Get used to it, there are not such formulations on the exam ... So be it, I will translate it. Only for you!

The words "reduce the expression to ..." mean to transform the expression so that its value hasn't changed and the appearance has changed in accordance with the task. So, in tasks 6 and 9, we must get a sine, inside which is the smallest positive angle. Everything else doesn't matter.

I will give the answers in order (in violation of our rules). But what to do, there are only two signs, and only four quarters ... You will not scatter in options.

6. sin57°.

7.cos(-57°).

8.cos57°.

9.-sin(-57°)

I suppose that the answers to questions 6-9 confused some people. Especially -sin(-57°), right?) Indeed, in the elementary rules for counting angles there is room for errors ... That is why I had to make a lesson: "How to determine the signs of functions and give angles on a trigonometric circle?" In Section 555. There tasks 4 - 9 are sorted out. Well sorted, with all the pitfalls. And they are here.)

In the next lesson, we will deal with the mysterious radians and the number "Pi". Learn how to easily and correctly convert degrees to radians and vice versa. And we will be surprised to find that this elementary information on the site enough already to solve some non-standard trigonometry puzzles!

If you like this site...

By the way, I have a couple more interesting sites for you.)

You can practice solving examples and find out your level. Testing with instant verification. Learning - with interest!)

you can get acquainted with functions and derivatives.

- In contact with 0

- Google+ 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0