It starts in the right nostril, then divides into two halves, goes around the entire head, including the neck, passes through the opening of the beak, and then becomes one again - sounds creepy, doesn't it? But this is precisely the structure of the bird's tongue, which has the longest tongue in the world.

Exclusive language

All of us, if we have not seen, then certainly heard how a woodpecker regularly taps on a tree trunk. In an attempt to find food, this bird has to expose the trunk of a tree, then gouge a hole in the wood, and then use its long tongue, which, due to its unique structure and length, is able to reach from the depths of larvae and insects.

The woodpecker's thin and sticky tongue will easily get a treat even from ant passages. Thanks to the nerve endings located on the tongue, the woodpecker is not mistaken with the prey, which it has to catch by touch.

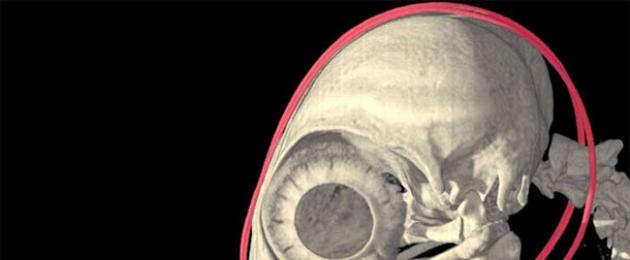

In most feathered creatures, the tongue is held by the back of the beak and is located in the mouth. In a woodpecker, pay attention to the picture, the tongue begins to grow from the right nostril! In a woodpecker, when it is not engaged in food extraction, the tongue is in a folded form. Placed in the nostril and under the skin that protects the skull.

Evolution or intelligent design?

Many people also remember from the school course in biology about natural selection and mutations, during which those individuals who have managed to adapt to the world around them continue their life path and development. But what advantage does a bird gain if its tongue moves from its usual place to the right nostril, and even begins to grow backwards? Further development of events would show that such a bird simply starved to death.

The woodpecker gained the upper hand when its tongue made a full circle around its head and settled in its usual place in its beak. Despite the fact that the woodpecker has a unique language structure, evolutionists have no doubt that this bird is descended from other birds with a standard language. But it is argued that the woodpecker's tongue is the result of intelligent design.

Woodpecker food

The bird, which has the longest tongue in the world, has the finest hearing. The quietest sound made by wood-eating insects will not be ignored. Woodpeckers eat what they find in the bark, under the bark, inside the bark, in wood.

Some of the woodpeckers hunt not only in wood; anthills and stumps are used to search for food. Some individuals are looking for larvae in the earth's thickness. Usually the bird's diet consists of bugs, larvae, ants, worms and caterpillars. Northern brothers are not averse to eating nuts.

Woodpecker family

Woodpeckers are monogamous, loyal to their mate all season. The birds breed a couple of times a year. Every year woodpeckers gouge themselves a new dwelling, they do not use other people's buildings. Woodpeckers prefer to use softwood trees to build their dwellings. It happens that the length of such a dwelling reaches half a meter. Woodpeckers use sawdust as bedding.

Woodpeckers in nature

Woodpeckers, for active pest control, were nicknamed "forest orderlies". They bring obvious help in forests that have been standing for years, where there are many old trees. But in young growth, woodpeckers are more likely to harm than benefit. The abundance of hollows spoils the structure of a young tree. If the same tree is regularly hammered for three to four years, as suckers like to do, then it will die.

In zoos, these birds are rare, but they get used to people quickly enough. We figured out a little with the question of which bird has the longest tongue, it's time to pay attention to other representatives of the vertebrate world.

Bat

In the mammalian world, the recently discovered bat in Ecuador has become the champion in tongue length. The length of this organ is 3.5 times the length of the owner's body and is 8.5 cm. It was possible to measure the tongue of this lady when she was treated to sugar-free water in a narrow and long test tube.

Australian echidna

An egg-laying mammal has an elongated nose. At the end of which both the nose and the mouth are located, there is a very thin and long tongue inside. If the animal sticks out its tongue, then we will see 18 centimeters of the tongue covered with sticky liquid.

Chameleons

This lizard's tongue reaches half a meter. The length of this organ depends on the size of the chameleon, the larger the animal, the longer its tongue. This representative of the squamous detachment straightens its tongue for hundredths of a second - the elusive movement can be seen only with the help of slow motion.

Ant-eater

An anteater is a toothless animal, although no teeth are needed with a 60 cm sticky tongue. Ants and termites are eaten. In one minute, the anteater can stick out and draw back its tongue more than one and a half hundred times.

Giraffe

The tallest mammal on Earth sometimes lacks its own height. The animal compensates for this shortcoming with its long tongue. With the help of a 45-centimeter tongue, the animal makes its own food, consisting of the leaves of trees and shrubs.

Have you seen how a woodpecker hollows a tree? Well, or at least you heard. But what happens next? How he gets sweets from under the bark and why the tongue of a woodpecker is considered the longest, and most importantly - how it fits with the theory of step-by-step evolution, we will tell in this article.

After the woodpecker removes the bark from the tree, drills a hole in it and finds insect passages, it uses its long tongue to reach insects and larvae from the depths. Its tongue is able to lengthen five times, and it is so thin that it even goes into ant passages. The tongue is equipped with nerve endings that determine the type of prey, and glands that secrete a sticky substance, thanks to which insects stick to it like flies to sticky tape.

While the tongue of most birds is attached to the back of the beak and sits in the mouth, the woodpecker's tongue does not grow from the mouth, but from the right nostril! Coming out of the right nostril, the tongue splits into two halves, which cover the entire head with the neck, and exit through the opening in the beak, where they join again. Simply amazing! Thus, when the woodpecker is flying and not using its tongue, it is kept curled up in the nostril and under the skin behind the neck!

Evolutionists believe that the woodpecker descended from other birds with a normal tongue that emerged from its beak. If a woodpecker's tongue was formed only by random mutations, they would first have to move the woodpecker's tongue into his right nostril and point it backwards, but then he would starve to death! A step-by-step evolution scenario (through mutation and natural selection) could never have created a woodpecker tongue, since turning the tongue backwards would not provide any advantage to the bird - the tongue would be completely useless until it made a full circle around its head, returning at the base of the beak.

The unique design of the woodpecker's tongue clearly indicates that it is the result of intelligent design. A step-by-step evolution scenario could never create a woodpecker's tongue, since turning the tongue backwards would be useless until it makes a full circle around the head, returning to the base of the beak.

Is it really?

Woodpecker Design is said to be an absolutely insoluble problem for those who believe in evolution. How could a system of special shock absorbers evolve in woodpeckers step by step? If it had not been for it at the very beginning, all woodpeckers would have taken out their brains long ago. And if there was once a time when woodpeckers did not need to drill holes in trees, they would not need shock absorbers.

Suppose a woodpecker has a long tongue attached to the right nostril, but it completely lacks a strong beak, neck muscles, shock absorbers, etc. How would a woodpecker use its long tongue if it had no other auxiliary apparatus? On the other hand, let's say that the bird has all the tools necessary for drilling holes in the tree, but does not have a long tongue. He would have poked holes in the tree, looking forward to a delicious meal, but he could not get the insects. The point is that in an irreducibly complex system, nothing can work if everything does not work.

For those who believe in woodpecker evolution, the fossil record presents another major challenge. There are practically no fossil woodpeckers in the annals, so it is impossible to track the supposed gradual development of woodpeckers from simple birds in it.

Currently, many creationists and creationist organizations have created sites where the woodpecker is presented as an example of an organism that "could not have evolved."

In making such a claim, they provided a wealth of information regarding the anatomy and physiology of the woodpecker, especially regarding its surprisingly long tongue, which is either garbled or clearly false.

The purpose of this site is to offer accurate information to those who might otherwise take the creationist erroneous claims at face value.

Woodpeckers (family Picidae) are well-known birds whose unique anatomy allows them to exploit unusual ecological niches. Many species in this family exhibit interesting adaptations that allow them to punch holes in hard, rot-free wood in search of insects and other prey.

Woodpecker's tongue is one of the more exciting things among these devices. Unlike the human tongue, which is mainly a muscular organ, the tongues of birds are rigidly supported by a cartilage-bone skeleton called the "hyoid apparatus". All higher vertebrates have a hyoid in one form or another; You can feel the horns of your own U-shaped hyoid bone by squeezing the top of your throat between your thumb and forefinger. Our hyoid serves as an attachment site for some of the muscles in our throat and tongue.

The Y-shaped hyoid apparatus of birds, however, extends right up to the very tip of their tongue. The “Y” fork is just in front of the throat, and this is where most of the hyoid muscles attach. Two long formations, "horns" of the hyoid, grow posterior to this area and form attachment points for the traction muscles that originate in the lower jaw. The "horns" of the hyoid of some species of woodpeckers have a very impressive structure, since they can extend to the crown of the head, and in some species they stretch around the orbit or even extend to the nasal cavity.

The unusual appearance of the woodpecker's "tongue skeleton" inspired creationists to use it as an example of an entity too bizarre to evolve through random mutations that produced viable intermediates. However, as the information below shows, the strange language of woodpeckers is really just an elongated version of the same one that all birds have, in fact an excellent example of how anatomical features can be transformed into new forms by mutation and natural selection.

Several creationist sites and articles I have read have stated that the woodpecker's tongue is “anchored in the right nostril” or “grows back” from the nasal cavity. The original connections between the woodpecker’s hyoid apparatus and the rest of its body are muscles and ligaments. that attach the hyoid to the jaw bone, throat cartilage, and base (rather than apex) of the skull - the same state of affairs as in all other birds. In adults of several species, the hyoid horns may eventually grow forward and grow into the nasal cavity from above - however, the hyoid and tongue, of course, do not grow FROM the nasal cavity.

Figure 3a: The jawbone and hyoid apparatus of the domestic chicken (Gallus gallus)

Figure 3b: The hyoid apparatus and associated musculature and viscera of the red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus)

Compare with chicken hyoid (see above). Also notice the branchomandibular muscles (Mbm) that wrap around the hyoid horns and attach to the jaw. The attachment features of the stylobilled woodpecker are the same, but the Mbm horns and muscles are longer.

The bird's tongue itself covers the anterior part of the hyoid apparatus - its posterior parts, including the hyoid horns, function as supporting structures.

The length of the hyoid horns varies very insignificantly in different birds, but they are all very similar in function. The domestic chicken (Figure a) is a well-studied example of a bird that is not closely related to the woodpecker but still has all the essential features of the woodpecker hyoid (Figure b).

The chicken's hyoid horns and the sheath of the ligaments in which they are located (fascia vaginalis - Fvg) extend backward on either side of the throat, then curve behind the chicken's ears towards the back of the head (Figure 3a).

The sheath itself is formed from a sac of lubricating fluid into which the horns grow as it develops. This lubricant gives the horns some freedom to slide forward or backward on the sheath as the tongue protrudes or is pulled into the mouth. There are several elastic ligaments between the sheath and the horns, but they, of course, are not firmly attached to the skull.

Notice the attachment points of the branchiomandibular muscles (labeled "Mbm") that attach near the ends of the hyoid horns, extend along the sheath, and attach to the middle of the jawbone (attachments labeled "Mbma" and "Mbmp"). These are the muscles that move the horns down the sheath, press them against the skull and thereby pull the hard bird's tongue forward.

Thus, paired hyoid horns in a bird serve only as an attachment point for muscles that actually begin on the lower jaw - the contraction of these muscles pulls the horns and the entire hyoid apparatus forward and outward relative to the skull, pushing the tongue out of the mouth like a spear.

Once this concept is understood, it becomes evident that lengthening the hyoid horns and the muscles attached [to them], without any other changes in general structure or function, would be guaranteed to give the bird a longer tongue and allow it to stick that tongue further out of the mouth. In fact, this is exactly what happens as the young woodpecker matures.

Figure 4: Diagram of the structure of the skull and hyoid apparatus of short- (left) and long-tongued (right) woodpeckers. The reddish-brown stripes show the action of the branchiomandibular muscle (Mbm) during tongue extension. The sites of Mbm attachment to the hyoid horns and the mandibular bone are shown in purple. Compare with the attachment sites "mbm", "mbma" and "mbmp" in Figure 3. The green arrows show the direction of movement of the hyoid horns during Mbm contraction.

When the awl-billed woodpecker has just hatched from its egg, its hyoid horns extend only behind its ear openings, like in a chicken. As it grows, the sheath, horns, and muscles become longer, curving forward over the head and reaching the nasal cavity.

In birds with longer horns, the horns are most relaxed at rest, and the Mbm contraction straightens and presses them tightly against the skull when the tongue is extended. Thus, in some species, tip slip may be minimal (see Figure 4).

Compare the horns of a chicken hyoid (Fig. 3) and an adult stylobilled woodpecker (Fig. 4, 5.1). Note that while the stylobranch woodpecker's horns are much longer, they each contain two bones (the ceratobranchiale and the epibranchiale) and one tiny joint with a piece of cartilage at the tip of the upperbranch bone - just like a chicken's. There are several other minor morphological differences, such as the presence of the urohyale (UH) bone in the chicken, but the full agreement is clear.

As mentioned earlier, the hyoid horns of the styloid woodpecker chick (and other long-tongued woodpeckers) are rather short (see Figure 5.2) and are comparable to those of short-tongued woodpecker species such as the sucker woodpecker (Figure 5.3), which, in turn, has hyoid the horns are no larger than those of many songbirds.

Is the woodpecker the result of intelligent design?

Figure 5:

1. The hyoid of the awl-billed woodpecker (Colaptes auratus) (adult)

2. The hyoid of the awl-billed woodpecker (Colaptes auratus) (recently hatched)

3. Hyoid of the red-capped sucker woodpecker (Sphyrapicus varius nuchalis) (adult)

Only as they grow older do the hyoid horns of the stylobilled woodpecker grow to the crown, then forward and into the nasal cavity, where the sheath is connected to the nasal septum. This makes adaptive sense, as the young Awl-billed Woodpecker is being fed by its parents, and a long tongue would only get in the way.

The genetic changes required for this modification are very small. No new structures are required, just a longer growth period to lengthen existing structures. It is likely that in the ancestral species of woodpecker, which began to search for beetle larvae deeper in the wood, woodpeckers with mutations that led to an increase in the size of the hyoid horns turned out to be more adaptable, because they could stick out their tongue further, getting to their prey. Some woodpeckers had no need for a long tongue at all, and therefore genes were selected that shortened the horns of the hyoid. A sucking woodpecker (2), for example, punches narrow holes in trees and then uses its short tongue to feed on the sap that flows onto the trunk's surface (and the insects that stick to it).

Different species of woodpeckers have many other interesting adaptations. Some species, for example, have altered joints between certain bones in the skull and upper jaw, as well as muscles that contract to absorb the shock of chiseling wood. A strong neck and tail feather muscles, as well as a chisel-like beak, are other chiselling devices found in some species. The same creationist sources that provide inaccurate information about language often argue that the significant amount of adaptation found in woodpeckers is an argument against evolution. They state that all these adaptations would have to appear "at the same time," otherwise they would all be useless. Of course, this kind of argument ignores the fact that many species of living woodpeckers do not possess such adaptations, or do not fully possess them.

The awl-billed woodpecker, for example, uses its long tongue mainly to grab prey on the ground or from under loose bark. It has few shock-absorbing adaptations and prefers to feed on the ground or break off pieces of rotten wood and bark; this is a behavior observed in birds not belonging to the woodpecker family. A "sequential chain" based on the structure of the skull, from little to highly specialized for chiselling wood, is observed in various genera (groups of related species) of living woodpeckers. In his classic Birds of America, John James Audubon describes the slight differences in the length of the hyoid horns found in various species of modern woodpeckers.

Whiners and woodpeckers, members of the woodpecker family that look like a kind of cross between songbirds and woodpeckers, have many adaptations similar to those of woodpeckers, such as long tongues. However, they do not have rigid tail feathers and some other traits of specialization for chiselling wood. They are believed to be similar to the ancestral forms of today's specialized woodpeckers.

Let me remind you of the features of woodpeckers:

1. Due to the huge energy consumption, the woodpecker is constantly hungry. For example, a black woodpecker (native to North America) can eat 900 beetle larvae or 1000 ants in one sitting; the green woodpecker eats up to 2,000 ants a day. This truly “ravenous appetite” has a purpose: woodpeckers play an important role in controlling insects, helping to limit the spread of tree diseases by eliminating disease vectors. Thus, the woodpecker bird helps to preserve the forests.

2. A woodpecker is capable of striking a tree at a speed of 20-25 times per second (which is almost twice the speed of a machine gun) 8000-12000 times a day!

3. When this bird strikes a tree, it uses incredible power. If the same force was applied to the skull of any other bird, its brain would quickly turn to mush. Moreover, if a person hit his head against a tree with the same force, he, if he survived after such a concussion, would receive a very serious brain injury. However, a number of physiological structural features of the woodpecker prevent all these tragedies.

4. When a woodpecker bangs on a tree at a speed of up to 22 times per second, his head experiences overloads reaching 1000 g (a person would be “knocked out” at 80–100 g). How do woodpeckers manage to withstand such pressure? David Johanz writes:

“Every time a woodpecker strikes a tree, it experiences a stress equal to 1000 gravitational forces. This is more than 250 times the stress experienced by an astronaut when launching a rocket ... In most birds, the bones of the beak are connected to the bones of the skull - the bones that surround the brain. But in woodpeckers, the skull and beak are separated from each other by a cloth that looks like a sponge. It is this “pillow” that takes the brunt of the blow every time a woodpecker's beak plunges into a tree. The woodpecker's shock absorber works so well that, according to scientists, man has not yet come up with anything better. "

In addition, both the beak and the woodpecker's brain itself are surrounded by a special pillow that softens the blows.

5. During "drilling operations" the woodpecker's head moves at a speed more than twice the speed of a bullet when fired. At this speed, any blow struck even at a slight angle would simply rip apart the bird's brain. However, the neck muscles of the woodpecker are so well coordinated that its head and beak move synchronously in an absolutely straight line. What's more, the blow is absorbed by special muscles in the head that pull the woodpecker's skull away from its beak every time it strikes.

6. The woodpecker has an extremely strong beak that most other birds do not have. Its beak is strong enough to forcefully enter a tree without folding like an accordion. After all, a woodpecker knocks on wood with a speed of about 1000 beats per minute (almost twice the speed of a combat machine), and its speed at the moment of impact is up to 2000 km per hour.

7. The tip of the woodpecker's beak is shaped like a chisel, and like a chisel it is able to penetrate the hardest wood. However, unlike a construction tool, it never needs to be sharpened!

8. Two toes on the woodpecker's foot are directed forward, and two are directed backward. It is this structure that makes it easy for him to move up, down and around tree trunks (most birds have three fingers pointing forward and one back). In addition, the suspension system, which includes the tendons and muscles of the legs, sharp claws and stiff tail feathers, on the tips of which are spikes for support, allows the woodpecker to absorb the force of lightning-fast repetitive blows.

9. When a woodpecker knocks on wood at a speed of up to 20 times per second, its eyelids close each time a moment before the moment when its beak approaches its target. This is a kind of protection mechanism for the eyes from the chips. Closed eyelids also hold the eyes in place and prevent them from flying out.

10. In a recent study, scientists at the University of California, Berkeley found four shockproof benefits of woodpeckers:

“A firm but resilient beak; a sinewy, springy structure (hyoid, or hyoid bone) that covers the entire skull and supports the tongue; the area of cancellous bone in the head; a way of interaction between the skull and cerebrospinal fluid, suppressing vibration. ”The woodpecker's shock absorption system is not based on any one factor, but is the result of the combined action of several interdependent structures.

It starts in the right nostril, then divides into two halves, goes around the entire head, including the neck, passes through the opening of the beak, and then becomes one again - sounds creepy, doesn't it? But this is precisely the structure of the bird's tongue, which has the longest tongue in the world.

Exclusive language

All of us, if we have not seen, then certainly heard how a woodpecker regularly taps on a tree trunk. In an attempt to find food, this bird has to expose the trunk of a tree, then gouge a hole in the wood, and then use its long tongue, which, due to its unique structure and length, is able to reach from the depths of larvae and insects.

The woodpecker's thin and sticky tongue will easily get a treat even from ant passages. Thanks to the nerve endings located on the tongue, the woodpecker is not mistaken with the prey, which it has to catch by touch.

In most feathered creatures, the tongue is held by the back of the beak and is located in the mouth. In a woodpecker, pay attention to the picture, the tongue begins to grow from the right nostril! In a woodpecker, when it is not engaged in food extraction, the tongue is in a folded form. Placed in the nostril and under the skin that protects the skull.

Evolution or intelligent design?

Many people also remember from the school course in biology about natural selection and mutations, during which those individuals who have managed to adapt to the world around them continue their life path and development. But what advantage does a bird gain if its tongue moves from its usual place to the right nostril, and even begins to grow backwards? Further development of events would show that such a bird simply starved to death.

The woodpecker gained the upper hand when its tongue made a full circle around its head and settled in its usual place in its beak. Despite the fact that the woodpecker has a unique language structure, evolutionists have no doubt that this bird is descended from other birds with a standard language. But it is argued that the woodpecker's tongue is the result of intelligent design.

Woodpecker food

The bird, which has the longest tongue in the world, has the finest hearing. The quietest sound made by wood-eating insects will not be ignored. Woodpeckers eat what they find in the bark, under the bark, inside the bark, in wood.

Some of the woodpeckers hunt not only in wood; anthills and stumps are used to search for food. Some individuals are looking for larvae in the earth's thickness. Usually the bird's diet consists of bugs, larvae, ants, worms and caterpillars. Northern brothers are not averse to eating nuts.

Woodpecker family

Woodpeckers are monogamous, loyal to their mate all season. The birds breed a couple of times a year. Every year woodpeckers gouge themselves a new dwelling, they do not use other people's buildings. Woodpeckers prefer to use softwood trees to build their dwellings. It happens that the length of such a dwelling reaches half a meter. Woodpeckers use sawdust as bedding.

Woodpeckers in nature

Woodpeckers, for active pest control, were nicknamed "forest orderlies". They bring obvious help in forests that have been standing for years, where there are many old trees. But in young growth, woodpeckers are more likely to harm than benefit. The abundance of hollows spoils the structure of a young tree. If the same tree is regularly hammered for three to four years, as suckers like to do, then it will die.

In zoos, these birds are rare, but they get used to people quickly enough. We figured out a little with the question of which bird has the longest tongue, it's time to pay attention to other representatives of the vertebrate world.

Bat

In the mammalian world, the recently discovered bat in Ecuador has become the champion in tongue length. The length of this organ is 3.5 times the length of the owner's body and is 8.5 cm. It was possible to measure the tongue of this lady when she was treated to sugar-free water in a narrow and long test tube.

Australian echidna

An egg-laying mammal has an elongated nose. At the end of which both the nose and the mouth are located, there is a very thin and long tongue inside. If the animal sticks out its tongue, then we will see 18 centimeters of the tongue covered with sticky liquid.

Chameleons

This lizard's tongue reaches half a meter. The length of this organ depends on the size of the chameleon, the larger the animal, the longer its tongue. This representative of the squamous detachment straightens its tongue for hundredths of a second - the elusive movement can be seen only with the help of slow motion.

Ant-eater

An anteater is a toothless animal, although no teeth are needed with a 60 cm sticky tongue. Ants and termites are eaten. In one minute, the anteater can stick out and draw back its tongue more than one and a half hundred times.

Giraffe

The tallest mammal on Earth sometimes lacks its own height. The animal compensates for this shortcoming with its long tongue. With the help of a 45-centimeter tongue, the animal makes its own food, consisting of the leaves of trees and shrubs.

Some birds have very long tongues, there are owners of tongues of extraordinary length among animals. In addition, there is evidence for long languages in humans. It is interesting to know about all these "champions".

The longest tongue of a bird

Oddly enough, but the woodpecker has the longest tongue among all birds. This is not a large bird, its sizes vary from fifteen to fifty-three centimeters, while the tongue reaches sizes from fifteen to twenty centimeters. It turns out that the length of the tongue is several times longer than the beak.Woodpeckers live almost everywhere, but wooded areas are preferable for their residence. The reason is in the way of life and nutrition of these birds. Their main food is insects living on trees. When foraging for food, the woodpecker uses its beak like a jackhammer, making holes in the bark of trees in this way. This opens up food passages in which insects hide. With its amazing length tongue the bird takes them out of these holes.

It is surprising that a woodpecker's tongue can stretch out and become so thin that it can easily penetrate even an ant's passage. There is a special gland on the tongue, due to which the tongue becomes covered with a sticky liquid, which is why insects simply stick to it.

The tongue is anchored in the right nostril, not in the mouth. At the same time, it, dividing into two parts, encircles the head and neck, then it is inserted into the beak through a special hole, where it connects again. It turns out that at a time when the woodpecker does not use its tongue, it is in the back of the neck, under the skin, and also in the nostril.

A number of experts argue that such a structure of the language is evidence of intelligent activity, and not the result of gradual evolution.

Long Tongue Girls

There is such an expression as "too long tongue." So often they say about those who do not mind gossiping or discussing any person. However, in the world people have long languages in the literal, and not only in the figurative sense of the word. It is not clear how an extra-long tongue fits in the mouth of such people.

There are many photos on the Internet in which you can see girls and not only, demonstrating their long tongues. Annika Imler is the official long-tongued woman. The outer part of her tongue is seven centimeters. Another record holder is Chanel Tapper, who lives in California. The length of her tongue is 9.8 centimeters.

The longest tongue in an animal

There are a large number of animals with very long tongues. Until recently, it was believed that a chameleon has the longest tongue. In this animal, the length of the tongue and the length of the body are always approximately the same. On average, the length of the tongue reaches fifty centimeters. In a large and long individual, the tongue is correspondingly longer. It is impossible to see it elongated in full length with the naked eye. Only slow motion can help, since the chameleon's tongue throws out only 0.05 seconds. By making accurate "shots" with their tongue, animals provide themselves with food.

The longest tongue among known mammals is possessed by the South American bat, which is considered quite rare. Her tongue is 1.5 times longer than her body. The bat keeps its tongue in the ribcage, while the tongue somehow contracts three times and sits between the heart and sternum in a special place.

This mammal was discovered only in 2003 in Ecuador. The pioneer was an American biologist, who was quite surprised to find that the tongue was fifty percent longer than the body of a mouse. So, its length is about 8.5 centimeters, and the body length of this bat is about 5-6 centimeters.

The South American bat feeds on the nectar of a flower with an extremely long corolla. Its name is Centropogon nigricans. Only the tongue of this little bat can “reach” the nectar inside this flower. In half a second, the mammal's tongue has time to dive into the “flower tube” for nectar seven times. It turns out that these flowers can only be pollinated by this species of bats. One gets the impression that nature has created them for each other.

The longest tongue in the world

You can take stock by finding out who speaks the longest language in the entire world. The longest tongue in the world among animals has a chameleon, among all species of birds - a woodpecker, but among mammals it is a rare species of bat that lives in Ecuador. Among the people, the record holder is Stephen Taylor. With an average length of a human tongue of five centimeters, its tongue did not reach ten centimeters in length, only two millimeters. Measurements are made from the center of the upper lip to the very tip of the tongue, that is, only the outer part is measured.

It is impossible not to say about the length of the language of some more representatives of our planet. So, in snakes, the tongue can reach twenty-five centimeters in length, the tongue of cows reaches forty-five centimeters, the giraffe, trying to reach the leaves, stretches the tongue forty-five centimeters. The anteater, deprived of teeth, is forced to get food by means of a sixty centimeter tongue. The largest lizard (Komodo monitor lizard) has a tongue up to seventy centimeters long.

The owner of the longest in the world and at the same time the largest language is the blue whale, which is also called the blue whale. His tongue can be equal to three meters in length. The whale uses its tongue to filter krill, which enters its mouth along with water.

The chameleon and blue whale are definitely unique animals. But there are creatures that are simply amazing. As the website reporters found out, the hair of some dogs is longer than a meter, and some animals are more like plants. You can read more about this in the article on the most unusual animals in the world.

Subscribe to our channel in Yandex.Zen

When asked which bird has the longest tongue? given by the author Mila the best answer is The woodpecker has the longest, most amazing tongue. Looking for insects in the bark and trunks of trees, the woodpecker gouges a hole with its beak, but to get the larvae hidden in the wood, the length of the beak is not enough. Here a flexible tongue with horny hooks at the tip comes to the rescue: the woodpecker launches it into the tree passage and, having groped for its prey, deftly picks it up. The tongue, which is already long, can also be pushed out of the oral cavity using a long tape that goes around the entire skull and is attached to the nostril. The woodpecker tongue is often longer than the bird's body (10-15 cm). Do you imagine the tongue is larger than the length of the body? Even chameleons and frogs cannot boast of such a language, and they are recognized champions in this matter.

The tongue is round in cross-section, hard at the end and with tiny teeth at the edges. In the beak, the tongue is twisted like a spring. With a long thin snake, he famously "crawls" into all the nooks of the tree hollowed out and eaten by bark beetles.  It is sticky, spiked at the end and very long; the green woodpecker, for example, is able to stick it out of the mouth by 10 centimeters. All birds, except the woodpecker, have their tongues in their mouths - just like you and me. But this is unacceptable for a woodpecker: you cannot "store" such a tongue in your mouth - it will get tangled and turn into a ball. In order for such an insect device to fit in the throat, the evolution that created the woodpecker had to remove the tendon base of the tongue from the oral cavity and wrap it in a loop around the skull! Its extra-long tongue "grows" from the right nostril and, passing right under the skin, wraps the entire head! Everything is very neat and convenient.

It is sticky, spiked at the end and very long; the green woodpecker, for example, is able to stick it out of the mouth by 10 centimeters. All birds, except the woodpecker, have their tongues in their mouths - just like you and me. But this is unacceptable for a woodpecker: you cannot "store" such a tongue in your mouth - it will get tangled and turn into a ball. In order for such an insect device to fit in the throat, the evolution that created the woodpecker had to remove the tendon base of the tongue from the oral cavity and wrap it in a loop around the skull! Its extra-long tongue "grows" from the right nostril and, passing right under the skin, wraps the entire head! Everything is very neat and convenient.

Well, let's just say that the woodpecker's tongue keeps in the mouth. And what grows from the nostril is the tongue horns, the muscles that support the tongue.

"The sublingual apparatus consists of an elongated body that supports the base of the tongue and long horns. In some birds, such as woodpeckers, very long horns go around the entire skull. When the sublingual muscles contract, the horns slide along the connective tissue bed, and the tongue protrudes from the oral cavity almost the length of the beak ".

- In contact with 0

- Google+ 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0