Aimed at external expansion, land expansion, as well as global recognition Russian State.

Exactly at Catherine's reign Russia became in such a territorial form (for the most part) that it reached the Bolsheviks. Under her, all Russian lands were united, both according to the Western “color” scheme and according to the Russian scheme of division into large, small and new:

- White Rus'(Belarus; white - because Orthodox);

- Black Rus'(The Baltic states were pagan for a long time, and later Catholic);

- Great Rus' (everything is clear here);

- Red Rus'(or Red - that is, Southern Rus', right-bank Ukraine);

- Little Rus'(Little Russia - left-bank Ukraine - from Kyiv to Zaporozhye, and from the Dnieper to Poltava);

- New Rus'(Novorossiya - northern Black Sea region, or Southern Ukraine from Odessa to Don plus Crimea).

Having ascended the throne in 1762, Catherine saw the end Seven Years' War , most of which passed and became the result of the empress’s foreign policy Elizabeth. Catherine's husband Peter III ruled for only six months, but during this time he managed to seriously spoil the achievements of his predecessor. The historical paradox was that the German Catherine (of Prussian-Swedish origin) was more Russian than the Prussian-oriented Peter III Romanov.

The latter signed a separate peace with Prussia on April 14, 1762 and gave it all the conquered lands free of charge, that is, for nothing. Thus, the Anglo-Prussian coalition won not only in the colonies (Russia did not participate in this war), but also in Europe, where the Russian Empire could become the conductor of the entire European orchestra, but remained the first violin (which is also good, but it was so under Peter I).

In 1768, the Turkish Sultan (Ottoman Emperor) declared war on Russia under a far-fetched pretext (violation of borders by Russian troops during the persecution of the Poles). So it began Russian-Turkish war.

The war lasted 6 years. As a result, Russia defeated the Crimean Khanate, and the pro-Russian Shahin Giray became the new khan. For some reason, the Ottoman Empire was not satisfied with the results, and in 1787 a fire broke out. new stage war. Catherine II (or rather, her main commander Alexander Suvorov) approached the problem seriously, and in 1792 the Turks lost lands in the western Black Sea region to the Dniester (Moldova and Odessa region), Crimea became completely Russian for the first time, as did Azov, the Kerch Strait, Kuban and North Caucasus. The Turks realized that they had made a mistake, but it was too late to do anything, and they signed the Treaty of Jassy in order to preserve what was left. In addition to Suvorov, they became famous in this war Grigory Potemkin, Petr Rumyantsev and admiral Fedor Ushakov.

In 1764, with the participation of Catherine, Stanislav August became the Polish king, oriented towards cooperation with Russia. The Western-oriented Polish gentry staged an uprising, which was suppressed. However, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth has already found itself in a deep political crisis (like modern Ukraine). Austria and Prussia in 1772 began to brazenly tear Poland apart into pieces. Catherine could not stay away. The Austrians and Germans did not want to fight Russia, so all three partition of Poland passed peacefully (the first - 1772, the second - 1793 and the third - 1795). In general, Catherine annexed (and for the most part returned) to Russia such territories as all of Belarus, Courland (eastern Lithuania), Lithuania and Volyn (Right Bank Ukraine).

In 1783, the Kartli-Kakheti (Georgian) king Heraclius II of the Bagrateon dynasty asked for a Russian protectorate to ensure security from Persia (Iran) and Turkey (Ottoman Empire). In the same year it was concluded Treaty of Georgievsk. And in 1796, the Georgian lands completely became part of Russian Empire.

In 1789, the Swedes decided to take advantage of the Russian-Turkish war and attacked Russia, intending to regain the Baltic states and Finland. In 1790 they were defeated in battle of Vyborg. Catherine thought about moving the fleet north and punishing the Swedes, but at Rochensalm the Russian ships were battered by a sudden storm, and she abandoned this idea. In the same year, the Treaty of Veresal was signed, and Sweden renounced its claims.

By 1779, if we talk about countries with which Catherine did not fight, then she had two cooperation agreements in her hands - with Prussia and with Denmark. According to estimates at that time, the Russian-Prussian-Danish coalition could have been even stronger than the proposed coalition of England, France, Spain and Austria. In order for the latter to become stronger, they would have to involve the Ottoman Empire, but such an alliance (due to old differences) was extremely unlikely.

The only failures (and then only conditionally) of Catherine in foreign policy were two unrealized projects:

- Greek project(a plan to seize the European possessions of the Turks and Constantinople, with the goal of returning Orthodoxy to the capital of Byzantium);

- Persian campaign (destruction of Persia as a state in order to protect Transcaucasia and the North Caucasus from constant Persian raids).

Despite these failed plans, when Catherine the Great The Russian Empire, without exaggeration, became the most powerful state in the world, stretching from Western Europe to Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, and from the Arctic Ocean to Persia and Afghanistan.

The Russian Empress died on November 6, 1796 in St. Petersburg from a cerebral hemorrhage (apoplexy). That's right, the blow occurred in the latrine, but she died in the bedroom. All other conjectures of “historians” who are more interested in Catherine’s personal life than her social and political activity, are just a figment of the imagination.

9.3. Foreign policy of Catherine II

In the second half of the 18th century. foreign policy Russia was focused on solving problems in two main directions: southern and western (Diagram 123).

First of all, this concerned the southern direction, where there was an intense struggle with the Ottoman Empire for the Northern Black Sea region and it was necessary to ensure the security of Russia’s southern borders.

The implementation of the policy in the western direction was to strengthen Russia's position in Europe and was associated with participation in the partitions of Poland, as well as with opposition to France, in which in 1789–1794. happened bourgeois revolution and whose revolutionary influence was feared by the European monarchical states, and especially the Russian Empire.

Scheme 123

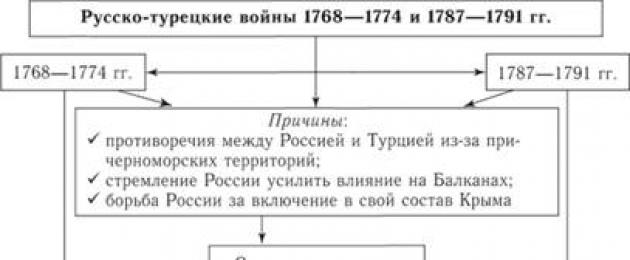

The solution of foreign policy problems related to the southern direction was complicated as a result of clashes with the Ottoman Empire, which led to two Russian-Turkish wars(diagram 124).

Scheme 124

Russo-Turkish War 1768–1774 The cause of the war was Russian interference in the affairs of Poland, which displeased Turkey. Catherine II supported the Polish king Stanislaw Poniatowski in the fight against the opposition (members of the so-called Bar Confederation). Pursuing one of the Confederate detachments, Russian Cossacks invaded Turkish territory and occupied it locality, located at the right tributary of the Southern Bug. In response, on September 25, 1768, Turkey declared war on Russia.

The fighting began in the winter of 1769, when the Crimean Khan, an ally of Turkey, invaded Ukraine, but his attack was repelled by Russian troops under the command of P.A. Rumyantseva.

Military operations were carried out on the territory of Moldova, Wallachia and at sea. The decisive year in the war was 1770, in which brilliant victories were won by the Russian army.

The fleet under the command of Admiral G.A. Spiridov and Count A.G. Orlova circumnavigated Europe, entered the Mediterranean Sea and in Chesme Bay off the coast of Asia Minor on June 24–26, 1770, completely destroyed the Turkish squadron.

On land, the Russian army led by P.A. won a number of victories. Rumyantsev. He used a new infantry combat formation - a mobile square. The troops “bristled” on all four sides with bayonets, which made it possible to successfully resist the numerous Turkish cavalry. In the summer of 1770, he won victories on the tributaries of the Prut - the Larga and Kagul rivers, which made it possible for Russia to reach the Danube.

In 1771, Russian troops under the command of Prince V.M. Dolgorukov took Crimea. In 1772–1773 A truce was concluded between the warring parties and peace negotiations began. However, they did not end in anything. The war resumed. The Russians crossed the Danube; in this campaign, A.V.’s corps won brilliant victories in the summer of 1774. Suvorov. Türkiye started talking about making peace. On July 10, 1774, a peace treaty was signed at the headquarters of the Russian command, in the town of Kyuchuk-Kainarzhi.

Russian-Turkish War 1787–1791 Confrontation between Russia and Ottoman Empire continued. Turkish Sultan Selim III began to demand the return of Crimea, recognition of Georgia as his vassal, and inspection of Russian merchant ships passing through the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits. On August 13, 1787, having received a refusal, he declared war on Russia, which was in alliance with Austria.

Military operations began with repelling an attack by Turkish troops on the Kinburn fortress (near Ochakov). The general leadership of the Russian army was carried out by the head of the Military Collegium, Prince G.A. Potemkin. In December 1788, Russian troops, after a long siege, took the Turkish fortress of Ochakov. In 1789 A.V. Suvorov, with smaller forces, twice achieved victory in the battles of Focsani and on the river. Rym-nike. For this victory he received the title of count and became known as Count Suvorov-Rymniksky. In December 1790, the troops under his command managed to capture the Izmail fortress, the citadel of Ottoman rule on the Danube, which was the main victory in the war.

In 1791, the Turks lost the Anapa fortress in the Caucasus, and then lost sea battle at Cape Kaliakria (near the Bulgarian city of Varna) in the Black Sea to the Russian fleet under the command of Admiral F.F. Ushakova. All this forced Turkey to conclude a peace treaty, which was signed in Iasi in December 1791.

Strengthening Russia's position in Europe in the second half of the 18th century. was associated with the weakening of the Polish state and its division between the leading European powers (diagram 125).

Scheme 125

The initiator of this process was Prussia. Its king, Frederick II, proposed to Catherine II to divide the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between its neighbors, especially since Austria had already begun the division, since its troops were located directly on the territory of this state. As a result, the St. Petersburg Convention of July 25, 1772 was concluded, which authorized the first partition of Poland. Russia received the eastern part of Belarus and part of the Latvian lands that were previously part of Livonia. In 1793, the second partition of Poland took place. Russia took control of Central Belarus with the cities of Minsk, Slutsk, Pinsk and Right Bank Ukraine, including Zhitomir and Kamenets-Podolsky. This caused an uprising of Polish patriots led by Tadeusz Kosciuszko in 1794. It was brutally suppressed by Russian troops under the command of A.V. Suvorov. The defeat of the rebels predetermined the third and final partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The lands of Courland, Lithuania, and Western Belarus were transferred to Russia. As a result, Russia captured more than half of all Polish lands. Poland lost its statehood for more than a hundred years.

The most important result of the divisions of Poland for Russia was not only the acquisition of vast territories, but also the transfer of the state border far to the west to the center of the continent, which significantly increased its influence in Europe. The reunification of the Belarusian and Ukrainian peoples with Russia freed them from the religious oppression of Catholicism and created opportunities for further development peoples within the East Slavic sociocultural community.

And finally, in late XVIII V. main task Russia's foreign policy has become a struggle against revolutionary France(see diagram 125). Catherine II, after the execution of King Louis XVI, severed diplomatic and trade relations with France, actively helped the counter-revolutionaries and, together with England, tried to put economic pressure on France. Only the Polish national liberation uprising in 1794 prevented Russia from openly organizing an intervention.

Russian foreign policy in the second half of the 18th century. was of an active and expansionist nature, which made it possible to include new lands in the state and strengthen its position in Europe.

Catherine II had a very energetic foreign policy. Her government solved several main foreign policy problems.

The first was to reach the shores of the Black Sea and gain a foothold there, secure the southern borders of the state from Turkey and Crimea.

The second task required continuing reunification of Ukrainian and Belarusian lands.

Nowhere have Russia's interests collided so sharply with the position of England and France as in the Turkish question. In September 1768, incited by France and Austria, Türkiye declared war on Russia. Attempts by the Turkish army to break into Russia were paralyzed by troops under the command of P.A. Rumyantsev. The campaign of 1768-1769 ended in failure for the Turks, but did not bring much success to the Russian army. The turning point came only in 1770, when hostilities unfolded on the lower Danube. P.A. Rumyantsev, with a difference of several days, won two brilliant victories over numerically superior enemy forces at Larga and Kagul (summer 1770). Success was also achieved in the Caucasus: the Turks were driven back to the Black Sea coast.

In the summer of 1770, the Russian fleet under the command of Alexei Orlov inflicted a crushing defeat on the Turks in Chesme Bay. In 1771, Russian troops occupied Crimea.

Catherine II's attempt to make peace in 1772 was unsuccessful (the conditions of Turkey were not satisfactory).

In 1773, during military operations, Türkiye capitulated. In 1774, a peace treaty was signed in Kuchuk-Kainardzhi, according to which the lands between the Bug and the Dnieper, including the sea coast, fortresses in Crimea, were given to Russia, and the Crimean Khanate was declared independent. Freedom of navigation was established on the Black Sea for Russian merchant ships with the right to enter the Mediterranean Sea. Kabarda was annexed to Russia.

The liberated army was deployed to suppress Pugachev's uprising.

The issue of Crimea remained controversial. The diplomatic struggle around him did not stop. Türkiye, in an ultimatum, demanded that Crimea be returned to it, that Georgia be recognized as a vassal possession, and that it be granted the right to inspect Russian merchant ships.

Russo-Turkish War 1787-1791 years began with an attempt by Turkey to land troops on the Kinburn Spit, but the attack was repulsed by troops under the command A.V.Suvorova. Then, in 1788, he took the powerful fortress of Ochakov, after which the Russian army launched an offensive in the Danube direction, which resulted in two victories, at Rymnik and Focsani. The capture of the impregnable fortress of Izmail by Suvorov in 1790 significantly brought the conclusion of peace closer.

The Swedes intervened in the Russian-Turkish conflict. Started Russian-Swedish war 1788-1790 As a result of this war, Sweden was forced to conclude the Varlev Peace Treaty.

At the same time, the Russian fleet under the command of F.F. Ushakov inflicted several defeats on the Turks at Cape Kaliakria. The Turkish fleet was forced to capitulate.

In December 1791, a peace treaty was signed in Iasi, establishing the border between Russia and Turkey along the Dniester. Russia received Ochakov and Crimea, but withdrew its troops from Georgia.

The second foreign policy task is annexation of Ukrainian and Belarusian lands to Russia- was decided by the government of Catherine II through the so-called divisions of Poland, which were carried out jointly with Prussia and Austria.

The Prussian king Frederick II, who dreamed of increasing his lands at the expense of his neighbors, turned to Catherine II with a proposal for a joint partition of Poland between Prussia, Austria and Russia. Since Russian forces were busy in the south in the war against Turkey, refusing Frederick II’s proposal meant transferring the initiative into the hands of Prussia. Therefore, in August 1772, the first agreement on the division of Poland between the three states was signed in St. Petersburg. Part of the Belarusian and Ukrainian lands went to Russia, Galicia with the large trading city of Lvov went to Austria, Pomerania and part of Greater Poland went to Prussia.

Second partition of Poland was preceded by an increase in revolutionary sentiment in Europe and, in particular, in Poland in connection with the revolution in France. In 1791, a constitution was introduced there, which, despite a number of shortcomings, was progressive and strengthened Polish statehood, which was contrary to the interests of Russia, Prussia and Austria. In 1793, Russia and Prussia made a second partition: Russia received the central part of Belarus and Right Bank Ukraine; Prussia - the indigenous Polish lands of Gdansk, Torun, Poznan. Austria did not receive its share under the second section. The 1791 Constitution was repealed. The second partition practically made the country completely dependent on Prussia and Russia. The patriotic forces of society rebelled in March 1794.

The movement was led by T. Kosciuszko. After several victories won by the rebels, a significant part of the Russian troops left Poland.

In the fall of 1794, Russian troops, led by A.V. Suvorov, took Prague (a suburb of Warsaw) by storm. In November 1794 the uprising was suppressed. The consequence of these events was third partition of Poland in October 1795. Western Belarus, Lithuania, Volyn and Courland went to Russia. To Prussia - the central part with Warsaw, Austria captured the southern part of Poland. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth ceased to exist as an independent state.

The socio-economic situation of Russia in the first half of the 19th century

At the beginning of the 19th century the population was 68 million people. More than 90% are peasants, 0.9 million are nobility, 0.5 million are clergy.

The industrial revolution proceeded slowly in Russia. The main reason for the backwardness was that Western countries demonstrated the success of economic development based on free enterprise and private initiative, while the Russian autocracy maintained serfdom, whose dominance created an insurmountable barrier to the development of new trends in the economy.

In autocratic-serf Russia, the main regulator of economic life was the interests of the state, and not the demands of the market. The industry, which operated under state control, had virtually no free competition.

But the all-Russian agricultural market gradually strengthened and domestic trade turnover increased. Industrial enterprises appeared, the products of which were intended for mass consumption - cotton and metalworking manufactories.

Feudal relations closed the channels for the formation of a layer of small and medium-sized owners in Russia.

Domestic policy of the Russian autocracy

The policy of Paul I was contradictory. On April 5, 1797 he published new decree about succession to the throne, according to which the throne was supposed to pass only through the male line from father to son, and in the absence of sons, to the eldest of the brothers.

Having become emperor, Paul tried to strengthen the regime by strengthening discipline and power in order to exclude all manifestations of liberalism and freethinking. The characteristic features of the reign of Paul I were harshness, instability and temper. He believed that everything in the country should be subject to the orders established by the monarch; He put efficiency and accuracy in the first place.

Paul I tightened the procedure for the service of nobles and limited the validity of letters of grant to the nobility. Prussian order was imposed in the army.

Laws were passed concerning the situation of peasants. In 1767 a decree was issued. Prohibiting the sale of peasants and household servants at auction. Prohibition of splitting up peasant families. The sale of serfs without land was prohibited. State-owned peasants received a 15-tithe mental allotment and special class management. The decree of 1796 finally prohibited the independent movement of peasants (from place to place). The widespread distribution of state peasants to the nobles continued.

In 1797, the Manifesto on the three-day corvee was published. He forbade landowners from using peasants for field work on Sundays, recommending that corvée be limited to three days a week.

The attack on noble privileges turned the nobility against Paul I. On the night of March 11-12, 1801, the emperor was killed by conspirators. The preparation of the conspiracy was led by the military governor of St. Petersburg P.A. Palen. Paul's eldest son, Alexander, was also aware of the plans of the conspirators.

Alexander 1 tried to implement a series of broad reforms developed in a circle of close friends ( Secret committee).

IN In 1802 he carried out ministerial reform: Instead of Peter's collegiums, on the principle of autocracy, ministries were created, headed by a minister, responsible to the tsar. All ministers united in Cabinet of Ministers.

Conducted reform in the education system. The country was divided into educational districts. The district was headed by a university.

Alexander tried to implement the program restrictions on serfdom. He stopped the distribution of state-owned peasants into private property. Decree of 1803 “On free cultivators” Peasants were allowed to purchase land from the landowner. However, the decree was overgrown with many subordinate bureaucratic conditions that it became impossible to apply it in life. In total, according to this decree, approximately 50 thousand families (0.5% of the total number of serfs) emerged from serfdom. By another decree, from 1801, non-nobles were allowed to buy uninhabited lands. Thus, the noble monopoly on land ownership was violated.

In 1808, Alexander brought closer to himself MM. Speransky. Speransky advocated the separation of powers into legislative, executive and judicial. According to Speransky’s project, under the chairmanship of the emperor, a State Council from ministers and Thought from those elected by the people. The Duma and the State Council had legislative power. Executive power belonged to the ministries, and judicial power belonged to the Senate and courts. Of the project, Alexander limited himself only to the creation of a State Council with legislative power.

|

Under Nicholas I (1825-1855), the era of “enlightened absolutism” ends. An attack begins on political, and partly economic rights nobility for the sake of strengthening the autocracy. Discipline among officials became stronger. Created under Nicholas I, the Third Department of the Imperial Chancellery, headed by A. X. Benckendorff and later A. F. Orlov, was engaged in the fight against dissent (as well as supervision of prisons, foreigners, the press, considered complaints from peasants against landowners, etc.). Censorship has increased. |

|

The correspondence was revealed. The dissatisfied went into exile, into the army in the Caucasus. After the liberal rule of Alexander I, government oppression caused sharp discontent among the upper strata. Nicholas I, who came to power after the Decembrist uprising, was terrified of the slightest activity in society and therefore suppressed it in every possible way. People who were executive, rather than capable and proactive, were more often appointed to leadership positions. At the same time, limited reforms were carried out. The legislation was streamlined (codified). In 1830, under the leadership of Speransky, the publication of the Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire began, in 1832 - the Code of Current Laws of the State. This made administrative practice easier. In 1837, under the leadership of P. D. Kiselev, a reform of the management of state peasants began to be carried out. Many of them received |

|

more land (often due to resettlement to uninhabited areas), first aid stations were built in their villages, and agricultural innovations were introduced. However, this was usually done by force, which caused dissatisfaction. Surplus products produced by state peasants were often exported to other regions. This caused unrest. The rights of landowners were limited - peasants could no longer be sent to mining work, and it was forbidden to sell them at auction for debts. |

However

main question

- about serfdom - remained unresolved. Nikolai did not solve it, fearing unrest in society. "Foreign Policy of Catherine II" Introduction

Klyuchevsky Vasily Osipovich. Russian historian (January 16, 1841 – May 12, 1911). The largest representative of Russian bourgeois-liberal historiography, academician (1900), honorary academician (1908) of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Proceedings: “Course of Russian history”, “Boyar Duma”

There were few events in Klyuchevsky’s life. One of the historian’s aphorisms: “The main biographical facts are books, major events- thoughts".

He studied at the Faculty of History and Philology of Moscow University. CM. Soloviev was his scientific supervisor. Klyuchevsky was the best lecturer during the entire period of existence of historical education in Russia.

At the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, Klyuchevsky gradually moved away from teaching and devoted all his energy to the creation of his main work, which put his name on a par with the names of Karamzin and Solovyov. The “Course of Russian History” was the result of all his scientific and teaching activities. The author set himself the task of covering a gigantic period from ancient times to the eve of the reform of 1861.

This abstract presents the view of V.O. Klyuchevsky. for one of the key periods of Russian history - the reign of Catherine II.

1. Catherine's position II on the throne

The century of our history, begun by the king-carpenter, ended with the empress-writer. Catherine had to smooth out the impression of a coup through which she came to the throne and justify the illegal appropriation of power.

Catherine made a double takeover: she took power from her husband and did not transfer it to her son, the natural heir of his father. There were rumors in the guard that were alarming for Catherine about the enthronement of Ivanushka, as he was called former emperor Ivan VI, also about why Tsarevich Paul was not crowned. It was even rumored in society that in order to consolidate her position on the throne, it would not hurt for Catherine to marry the former emperor. Catherine saw him soon after her accession to the throne and ordered him to be persuaded to take monastic vows. In the guard, circles and “parties” were formed, however, they did not have time to form a conspiracy (not everyone, even the participants in the coup, were satisfied with it, as they were not awarded enough). Catherine was especially alarmed in 1764 by the crazy attempt of the army second lieutenant Mirovich to free Ivanushka from the Shlisselburg fortress and proclaim him emperor - an attempt that ended in the murder of a prisoner who was insane in captivity, a terrible victim of the iniquities, the nursery of which was the Russian throne after the death of Peter I.

Catherine was not so much the culprit as the instrument of the coup: weak, young, alone in a foreign land, on the eve of divorce and imprisonment she surrendered into the hands of people who wanted to save her, and after the coup she could still not control anything. These people, now surrounding Catherine, led by the five Orlov brothers who had been promoted to counts, were in a hurry to reap the fruits of the “great incident,” as they called the June affair. They were strikingly lacking in education. They were not content with the awards they received, with the fact that Catherine gave them up to 18 thousand souls of peasants and up to 200 thousand rubles (at least 1 million in our money) of one-time dachas, not counting lifelong pensions. They besieged the empress, imposed their opinions and interests on her, sometimes directly asking for money. Catherine had to get along with these people. It was unpleasant and untidy, but not particularly difficult. She used her usual means, her inimitable ability to listen patiently and respond affectionately; when in a difficult situation, Catherine needed a little time and patience so that her supporters would have time to come to their senses and begin to have a proper relationship with her. It was much more difficult to justify the new government in the eyes of the people. Far from the capital, the deep masses of the people did not experience the personal charm of the empress, content with dark rumors and a simple fact that could be understood from popular manifestos: there was Emperor Peter III, but his wife, the empress, overthrew him and put him in prison, where he soon died.

These masses, which had long been in a state of ferment, could only be calmed by measures of justice and common benefit that were tangible for everyone.

2. Catherine II program

The popular activities of the new government had to simultaneously follow the national, liberal and class-noble directions. But this triple task suffered from internal contradiction. After the law of February 18, the nobility became contrary to all popular interests and even the transformative needs of the state. Whether for reasons of flexible thought or according to the instructions of experience and observation, Catherine found a way out of the inconveniences of her program. She divided the tasks and carried out each one in a special area of government activity.

National interests and feelings received wide scope in foreign policy, which was given full speed. A broad reform of regional administration and court was undertaken according to the plans of the then leading publicists of Western Europe, but mainly with the native goal of occupying the idle nobility and strengthening its position in the state and society . The liberal ideas of the century were also given their own area. The triple task developed into the following practical program: a strictly national, boldly patriotic foreign policy, complacently liberal, possibly humane methods of government, complex and harmonious regional institutions with the participation of the three estates, salon, literary and pedagogical propaganda of the educational ideas of the time, and a cautious but consistently conservative legislation with special attention to the interests of one class.

The main idea of the program can be expressed as follows: the permissive dissemination of the ideas of the century and the legislative consolidation of the facts of the place.

3. Foreign policy of Catherine II

Foreign policy is the brightest side government activities Catherine, who made the strongest impression on her contemporaries and immediate descendants. When they want to say the best that can be said about this reign, they talk about the victorious wars with Turkey, about the Polish partitions, about Catherine’s commanding voice in the international relations of Europe.

After the Peace of Nystadt, when Russia became firmly established in the Baltic Sea, two foreign policy issues remained on the agenda, one territorial, the other national. The first was to push the southern border of the state to its natural limits, to the northern coastline the Black Sea with the Crimea and the Sea of Azov and to the Caucasus Range. This eastern question in its historical production at that time. Then it was necessary to complete the political unification of the Russian people, reuniting with Russia what had been separated from it. western part. This Western Russian question .

Count Panin N.I. and his system

They expected the imminent death of the Polish king Augustus III. For Russia, it didn’t matter who would be king, but Catherine had a candidate whom she wanted to see through at all costs. This was Stanislav Poniatowski, a veil born for the boudoir, and not for any throne. This candidacy entailed a string of temptations and difficulties... Finally, the entire course of foreign policy had to be abruptly turned around. Until then, Russia maintained an alliance with Austria, which was joined by France during the Seven Years' War.

At first, after her accession to the throne, still poorly understanding matters, Catherine asked the opinions of her advisers about the peace with Prussia concluded under Peter III. The advisers did not recognize this peace as useful for Russia and spoke in favor of renewing the alliance with Austria. A.P. also stood for this. Bestuzhev - Ryumin, whose opinion she especially valued at that time. But a younger diplomat, a student and opponent of his system, Count N.I., stood next to him. Panin, teacher of Grand Duke Paul.

He was not only for peace, but directly for an alliance with Frederick, proving that without his assistance nothing could be achieved in Poland. Catherine stood strong for some time: she did not want to be an ally of the king, whom she publicly called the villain of Russia in the July manifesto, but Panin prevailed and for a long time became Catherine’s closest collaborator in foreign policy. The alliance treaty with Prussia was signed on March 31, 1764, when election campaigning was underway in Poland following the death of King Augustus III. But this union was just entering integral part as planned complex system international relations. After Panin’s death, Catherine complained that she had suffered enough with him as a lazy person during the first Turkish war. She was a white-handed diplomat, an idyllic diplomat. Panin became the conductor of an international combination unprecedented in Europe. According to his project, the northern non-Catholic states, including Catholic Poland, united for mutual support, to protect the weak by the strong. Its “active” members are Russia, Prussia and England. “Passive” - Sweden, Denmark, Poland, Saxony and other small states that had a desire to join the union. The combat purpose of the alliance is direct opposition to the southern alliance (Austro-Franco-Spanish). All that was required of the “passive” states was that in the event of clashes between both alliances they should not pester the southern one and remain neutral. This was the northern system that was sensational in its time. It's easy to notice her discomfort. It was difficult for states so diversely structured as autocratic Russia, constitutionally aristocratic England, soldier-monarchist Prussia and republican-anarchist Poland to act together and harmoniously. In addition, the members of the union had too few common interests and the northern system was not formalized in any international act.

Russia did not need the March 31 agreement. This alliance, the purpose of which was to facilitate Russia’s tasks in Poland, only made them even more difficult. The new king of Poland wanted to lead his fatherland out of anarchy through reforms. These reforms were not dangerous for Russia; It was even beneficial for her that Poland would become somewhat stronger and become a useful ally in the fight against the common enemy, Turkey. But Frederick did not want to hear about Poland’s awakening from political lethargy, and pushed Catherine into an agreement with Poland (February 13, 1768), according to which Russia guaranteed the inviolability of the Polish constitution and pledged not to allow any changes in it. Thus, the Prussian alliance armed Austria, its long-time ally, abandoned by it, against Russia, and Austria, on the one hand, together with France, incited Turkey against Russia (1768), and on the other, sounded the European alarm: a unilateral Russian guarantee threatens the independence and existence of Poland, the interests its neighboring powers and all political system Europe.

Thus, Frederick, relying on an alliance with Russia, tied the Russian-Polish and Russian-Turkish affairs into one knot and removed both matters from the sphere of Russian politics, making them European issues, thereby depriving Russian politics of the means to resolve them historically correctly - separately and without third party participation.

Eastern question

The goal of advancing the territory of the state in the south to its natural limits, to the Black and Azov seas, seemed too modest: desert steppes, Crimean Tatars- these are conquests that will not pay for the gunpowder spent on them. Voltaire jokingly wrote to Catherine that her war with Turkey could easily end with the transformation of Constantinople into the capital of the Russian Empire. The epistolary courtesy sounded like a prophecy.

War with Turkey

The Turkish War was a testing test for Catherine. During the six years of her reign, the empress managed to flap her wings widely, show her flight to Europe with her deeds in Poland, and at home - by convening a representative commission in 1767. Her name was already enveloped in a bright haze of greatness.

In such high spirits, Catherine greeted the Turkish war, for which she was not at all prepared. Ekaterina worked like a real boss General Staff, went into the details of military preparations, drew up plans and instructions, and hurried with all her might to build the Azov flotilla and frigates for the Black Sea.

At one of the first meetings of the council, which met on war matters under the chairmanship of the empress, Grigory Orlov proposed sending an expedition to the Mediterranean Sea. A little later, his brother Alexei Orlov indicated the direct goal of the expedition: if we go like this, go to Constantinople and free all Orthodox Christians from the heavy yoke, and drive them, the infidel Mohammedans, according to the word of Peter the Great, into the empty and sandy fields and steppes, their former homes. He himself asked to be the leader of the uprising of Turkish Christians.

But four years ago Catherine declared the fleet worthless. And he hastened to justify the review. As soon as the squadron, sailing from Kronstadt (1769) under the command of Spiridov, entered the open sea, one ship turned out to be unfit for further voyage. The Russian ambassadors in Denmark and England, who inspected the passing squadron, were struck by the ignorance of the officers, the lack of good sailors, the many sick people, and the despondency of the entire crew. The squadron moved slowly. Of the 15 large and small ships of the squadron up to Mediterranean Sea only eight made it. When A. Orlov examined them in Livorno, his hair stood on end: no provisions, no money, no doctors, no knowledgeable officers... However, having united with another Elfingston squadron that had approached in the meantime, Orlov chased the Turkish fleet and in the Strait of Chios near the fortress Chesme overtook the armada, which in terms of the number of ships was more than twice as strong as the Russian fleet. The horror of the situation inspired desperate courage, which spread to the entire crew. After a four-hour battle, the Turks took refuge in Chesme Bay (June 24, 1770). On June 26, the Turkish fleet crowded in the bay was burned. But Orlov failed to complete the campaign, break through the Dardanelles to Constantinople and return home by the Black Sea, as expected.

Amazing naval victories in the Archipelago were followed by similar land victories in Bessarabia at Larga and Cahul (July 1770). Moldavia and Wallachia are occupied, Bendery is taken; in 1771 they captured the lower Danube from Zhurzhi and conquered the entire Crimea.

Now let's compare the end of the war with its beginning to see how little they converge. The liberation of Christians was undertaken on various European outskirts of the Turkish Empire, Greeks in Morea, Romanians in Moldavia and Wallachia. The first was abandoned because they were unable to carry it out (with an insignificant Russian detachment, Orlov quickly raised the Morea, but could not give the rebels a strong combat structure and, having suffered a setback from the approaching Turkish army, abandoned the Greeks to their fate); they were forced to abandon the second to please Austria and ended up with the third, liberating the Mohammedans from the Mohammedans, and the Tatars from the Turks, which was not their intention when they started the war, and which absolutely no one needed, not even the liberated ones themselves. Crimea, which was occupied by Russian troops under Empress Anna and now re-conquered, was not worth even one war, but because of it they fought twice.

Second war with Turkey

This war was caused by oversights that prepared or accompanied the first. Crimea caused trouble under the auspices of Russia even more than before (infighting between the Russian and Turkish parties, the forced change of khans). Finally, they decided to annex Crimea to Russia, which led to the second war with Turkey. In view of this war, they left the northern system with the Prussian alliance and returned to the previous system of the Austrian alliance. Potemkin and Bezborodko replaced Panin. But the thinking remained the same, the usual inclination to build “Spanish castles,” as Catherine called her bold plans.

The second war (1787–1791), victorious and terribly costly in people and money, ended with how the first should have ended: with the retention of Crimea and the conquest of Ochakov with the steppe to the Dniester, the northern shore of the Black Sea was strengthened behind Russia, without Dacia and without second grandson on the throne of Constantinople.

Western Russian question

In the Polish question there were fewer political chimeras, but a lot of diplomatic illusions, self-delusion and, most of all, more contradictions. The question was the reunification of Western Rus' with the Russian state; This is how it stood back in the 15th century and continued in the same direction for a century and a half; This is how it was understood in Western Russia itself in the half of the 18th century. The Orthodox expected from Russia, first of all, equations of religious, religious freedom. The political equation was even dangerous for them.

Relation to Poland

In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, only the gentry enjoyed political rights. The upper strata of the Orthodox Russian nobility became Polish and Catholicized; what survived was poor and uneducated...

The Russian government achieved its goal and carried out at the Sejm, along with the Russian guarantee of the constitution and freedom of religion for dissidents, their political equalization with the Catholic gentry. The dissident equation set fire to all of Poland. It was a kind of Polish-gentry Pugachevism, with morals and methods no better than the Russian peasant. Although there is robbery of the oppressors for the right to oppress, here it is robbery of the oppressed for liberation from oppression.

The Polish government left it to the Russian empress to suppress the rebellion, while it itself remained a curious spectator of the events. There were up to 16 thousand Russian troops in Poland. This division fought with half of Poland, as they said then. The Confederates found support everywhere; the small and middle gentry secretly supplied them with everything they needed. Catherine was forced to refuse to allow dissidents into the Senate and the Ministry, and only in 1775, after the first partition of Poland, were they granted the right to be elected to the Sejm along with access to all positions. The orders of the autocratic-noble Russian rule fell so heavily on the lower classes that for a long time thousands of people fled to unemployed Poland, where life was more tolerable on the lands of the willful gentry. Panin therefore considered it harmful to give too broad rights to the Orthodox in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (escapes from Russia would increase). With such ambiguity in Russian politics, the Orthodox dissidents (fugitives) of Western Rus' could not understand what Russia wanted to do for them, whether she had come to completely liberate them from Poland or just to equalize them, whether she wanted to rid them of the priest or the Polish lord.

Partition of Poland

The Russian-Turkish War gave matters a wider course. The idea of dividing Poland had been floating around in diplomatic circles since the 17th century.

Under the grandfather and father of Frederick II, Peter I was offered the division of Poland three times. The war between Russia and Turkey gave Frederick II the desired opportunity. According to his plan, Austria, hostile to both of them, was involved in the alliance between Russia and Prussia, for diplomatic assistance to Russia in the war with Turkey, and all three powers received land compensation not from Turkey, but from Poland, which gave the reason for the war.

Three years of negotiations! In 1772 (July 25), an agreement followed between the three powers - shareholders. Russia has made poor use of its rights in both Turkey and Poland. The French minister maliciously warned the Russian commissioner that Russia would eventually regret the strengthening of Prussia, to which it had contributed so much. In Russia, Panin was also blamed for the excessive strengthening of Prussia, and he himself admitted that he had gone further than he wanted, and Grigory Orlov considered the treaty on the division of Poland, which so strengthened Prussia and Austria, a crime worthy of the death penalty.

Be that as it may, it will remain a rare factor in European history when the Slavic-Russian state during the reign with a national direction helped the German electorate with a scattered territory to turn into great power , a continuous wide strip stretching across the ruins of the Slavic state from the Elbe to the Neman. Thanks to Frederick, the victories of 1770 brought Russia more glory than benefit. Catherine emerged from the first Turkish war and from the first partition of Poland with independent Tatars, with Belarus and with great moral defeat, having raised and not justified so many hopes in Poland, in Western Russia, in Moldavia and Wallachia, in Montenegro, in Morea...

The meaning of sections

Western Rus' had to be reunited; instead they divided Poland. Russia annexed not only Western Rus', but also Lithuania and Courland, but not all of Western Rus', losing Galicia into German hands.

With the fall of Poland, the clashes between the three powers were not eased by any international buffer. Moreover, “our regiment has disappeared” - there is one less Slavic state; it became part of two German states; this is a major loss for the Slavs; Russia did not appropriate anything originally Polish; it only took away its ancient lands and part of Lithuania, which had once attached them to Poland.

Finally, the destruction of the Polish state did not save us from the struggle with the Polish people: 70 years have not passed since the third partition of Poland, and Russia has already fought three times with the Poles (1812, 1831, 1863). Perhaps, in order to avoid hostility with the people, their state should have been preserved.

Conclusion

What are the results and nature of the foreign policy of Catherine II?

The northern coast of the Black Sea from the Dniester to the Kuban was secured. The southern Russian steppes, the original shelter of predatory nomads, entered the Russian national economic circulation. A number of new cities arose (Ekaterinoslav, Kherson, Nikolaev, Sevastopol, etc.). The treaty of 1774 opened up free navigation in the Black Sea for Russian merchant ships. The navy in Sevastopol that emerged from the annexation of Crimea served as a support for the Russian protectorate over Eastern Christians. In 1791, Vice Admiral Ushakov successfully fought with the Turkish fleet in sight of the Bosphorus, and the thought of going straight to Constantinople again lit up in Catherine’s head. Almost all of Western Rus' was reunited.

In Russia, in remote backwaters, they remembered for a long time and said that during this reign our neighbors did not offend us and our soldiers defeated everyone and became famous. Bezborodko (the most prominent diplomat after Panin) told the young diplomats: “I don’t know how it will be with you, but with us, not a single cannon in Europe dared to fire without our permission.”

Literature

1. Soviet encyclopedic Dictionary. M. Soviet encyclopedia. 1985

2. Klyuchevsky V.O. On Russian history, M.: Education, 1993. Edited by Bulganov.

Abstract on the history of Russia

Catherine II had a very vigorous foreign policy, which ultimately turned out to be successful for the Russian Empire. Her government solved several main foreign policy problems.

The first was to reach the shores of the Black Sea and gain a foothold there, secure the southern borders of the state from Turkey and Crimea. Growth in marketability of production Agriculture The country was dictated by the need to own the mouth of the Dnieper, through which agricultural products could be exported.

The second task required continuing reunification of Ukrainian and Belarusian lands.

In the 60s of the 18th century, a complex diplomatic game was taking place in Europe. The degree of rapprochement between certain countries depended on the strength of the contradictions between them.

Nowhere have Russia's interests collided so sharply with the position of England and France as in the Turkish question. In September 1768, incited by France and Austria, Türkiye declared war on Russia. Attempts by the Turkish army to break into Russia were paralyzed by troops under the command of P.A. Rumyantsev. The campaign of 1768-1769 ended in failure for the Turks, but did not bring much success to the Russian army. The turning point came only in 1770, when hostilities unfolded on the lower Danube. P.A. Rumyantsev, with a difference of several days, won two brilliant victories over numerically superior enemy forces at Larga and Kagul (summer 1770). Success was also achieved in the Caucasus: the Turks were driven back to the Black Sea coast.

In the summer of 1770, the Russian fleet under the command of Alexei Orlov inflicted a crushing defeat on the Turks in Chesme Bay. In 1771, Russian troops occupied Crimea.

Catherine II's attempt to make peace in 1772 was unsuccessful (the conditions of Turkey were not satisfactory).

In 1773, the Russian army resumed military operations. A.V. Suvorov took the Turtukai fortress on the southern bank of the Danube and in 1774 won a victory at Kozludzha. Rumyantsev crossed the Danube and moved to the Balkans. Türkiye capitulated. In 1774, a peace treaty was signed in Kuchuk-Kainardzhi, according to which the lands between the Bug and the Dnieper, including the sea coast, fortresses in Crimea, were given to Russia, and the Crimean Khanate was declared independent. Freedom of navigation was established on the Black Sea for Russian merchant ships with the right to enter the Mediterranean Sea. Kabarda was annexed to Russia.

The liberated army was deployed to suppress Pugachev's uprising.

The fact that the peace treaty was only a respite was understood in both Russia and Turkey. The issue of Crimea remained controversial. The diplomatic struggle around him did not stop. In response to the machinations of the Turkish government, Russian troops occupied the peninsula in 1783. Türkiye, in an ultimatum, demanded that Crimea be returned to it, that Georgia be recognized as a vassal possession, and that it be granted the right to inspect Russian merchant ships.

Russo-Turkish War 1787-1791 years began with an attempt by Turkey to land troops on the Kinburn Spit, but the attack was repulsed by troops under the command A.V.Suvorova. Then, in 1788, he took the powerful fortress of Ochakov, after which the Russian army launched an offensive in the Danube direction, which resulted in two victories, at Rymnik and Focsani. The capture of the impregnable fortress of Izmail by Suvorov in 1790 significantly brought the conclusion of peace closer.

At the same time, the Russian fleet under the command of one of the most outstanding Russian naval commanders, Rear Admiral F.F. Ushakov, inflicted several defeats on the Turks in the Kerch Strait and off the islands of Tendra and Kaliakria. The Turkish fleet was forced to capitulate.

In December 1791, a peace treaty was signed in Iasi, establishing the border between Russia and Turkey along the Dniester. Russia received Ochakov and Crimea, but withdrew its troops from Georgia.

The second foreign policy task is annexation of Ukrainian and Belarusian lands to Russia- was decided by the government of Catherine II through the so-called divisions of Poland, which were carried out jointly with Prussia and Austria.

In October 1763, the Polish king Augustus III died. Russia took an active part in the election of the new king in order to prevent Poland from joining the coalition along with France, Turkey and Sweden. The situation was developing in favor of Russia, since England expected the conclusion of a Russian-English trade agreement that would be beneficial for itself, Prussia was not inclined to quarrel with Russia after the end of the Seven Years' War, France was in difficult economic situation. In Poland itself, a struggle between different factions for the throne unfolded. After a long struggle, on August 26, 1764, at the Coronation Diet Polish king, with the support of Russia, S. Poniatovsky was elected. Russia's activity displeased Prussia and Austria, who sought to increase their territories at the expense of Poland. This led to the partition of Poland, which began with the occupation of part of Polish territory by the Austrians.

The Prussian king Frederick II, who dreamed of increasing his lands at the expense of his neighbors, turned to Catherine II with a proposal for a joint partition of Poland between Prussia, Austria and Russia. Since Russian forces were busy in the south in the war against Turkey, refusing Frederick II’s proposal meant transferring the initiative into the hands of Prussia. Therefore, in August 1772, the first agreement on the division of Poland between the three states was signed in St. Petersburg. Part of the Belarusian and Ukrainian lands went to Russia, Galicia with a large trading city Lvov, to Prussia - Pomerania and part of Greater Poland.

Second partition of Poland was preceded by an increase in revolutionary sentiment in Europe and, in particular, in Poland in connection with the revolution in France. In 1791, a constitution was introduced there, which, despite a number of shortcomings, was progressive and strengthened Polish statehood, which was contrary to the interests of Russia, Prussia and Austria. In 1793, Russia and Prussia made a second partition: Russia received the central part of Belarus and Right Bank Ukraine; Prussia - the indigenous Polish lands of Gdansk, Torun, Poznan. Austria did not receive its share under the second section. The 1791 Constitution was repealed. The second partition practically made the country completely dependent on Prussia and Russia. The patriotic forces of society rebelled in March 1794.

The movement was led by one of the heroes of the War of Independence North America T. Kosciuszko. After several victories won by the rebels, a significant part of the Russian troops left Poland. T. Kosciuszko promised to abolish serfdom and reduce duties. This attracted a significant part of the peasantry to his army. However, there was no clear program of action; the enthusiasm of the rebels did not last long.

- In contact with 0

- Google+ 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0