- Scaliger "Discourse on the languages of Europeans." Ten Cate created the first grammar of the Gothic language, described the general patterns of strong verbs in Germanic languages, and pointed out vocalism in strong verbs.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Essay on the Origin of Languages. Numerous theories about the origin of language (social contract, labor cries). Diderot: “Language is a means of communication in human society.” Herder insisted on the natural origin of language. The principle of historicism (Language develops).

- Discovery of Sanskrit, the oldest written monuments.

V. Jones:

1) similarity not only in roots, but also in forms of grammar cannot be the result of chance;

2) this is a kinship of languages going back to one common source;

3) this source “perhaps no longer exists”;

4) in addition to Sanskrit, Greek and Latin, the same family of languages includes Germanic, Celtic, and Iranian languages.

At the beginning of the 19th century. Independently of each other, different scientists from different countries began to clarify the related relationships of languages within a particular family and achieved remarkable results.

Franz Bopp (1791–1867) went directly from the statement of W. Jonze and investigated comparative method conjugation of main verbs in Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and Gothic (1816), comparing both roots and inflections, which was methodologically particularly important, since the correspondence of roots and words is not enough to establish the relationship of languages; if the material design of inflections provides the same reliable criterion for sound correspondences - which cannot in any way be attributed to borrowing or accident, since the system of grammatical inflections, as a rule, cannot be borrowed - then this serves as a guarantee of a correct understanding of the relationships of related languages. Although Bopp believed at the beginning of his activity that the “proto-language” for Indo-European languages was Sanskrit, and although he later tried to include in the related circle of Indo-European languages such alien languages as Malay and Caucasian, but with his first work, and later, drawing on data from Iranian, Slavic, Baltic languages and the Armenian language, Bopp proved on a large surveyed material declarative thesis of V. Jonze and wrote the first “Comparative Grammar of the Indo-Germanic [Indo-European] Languages” (1833).

The Danish scientist Rasmus-Christian Rask (1787–1832), who was ahead of F. Bopp, followed a different path. Rask emphasized in every possible way that lexical correspondences between languages are not reliable; grammatical correspondences are much more important, since borrowing inflections, and in particular inflections, “never happens.”

Having started his research with the Icelandic language, Rask compared it primarily with other “Atlantic” languages: Greenlandic, Basque, Celtic - and denied them any kinship (regarding the Celtic, Rask later changed his mind). Rusk then compared Icelandic (1st circle) with the closest relative Norwegian and got 2nd circle; he compared this second circle with other Scandinavian (Swedish, Danish) languages (3rd circle), then with other Germanic (4th circle), and finally, he compared the Germanic circle with other similar “circles” in search of “Thracian” "(i.e., Indo-European) circle, comparing Germanic data with the testimony of Greek and Latin languages.

Unfortunately, Rusk was not attracted to Sanskrit even after he visited Russia and India; this narrowed his “circles” and impoverished his conclusions.

However, the involvement of Slavic and especially Baltic languages significantly compensated for these shortcomings.

1) The related community of languages follows from the fact that such languages originate from one base language (or group proto-language) through its disintegration due to the fragmentation of the carrier community. However, this is a long and contradictory process, and not a consequence of the “splitting of a branch in two” of a given language, as A. Schleicher thought. Thus the research historical development of a given language or group of given languages is possible only against the backdrop of the historical fate of the population that was the speaker of a given language or dialect.

2) The base language is not only a “set of ... correspondences” (Meilleux), but a real, historically existing language that cannot be completely restored, but the basic data of its phonetics, grammar and vocabulary (to the least extent) can be restored, which was brilliantly confirmed by the data the Hittite language in relation to the algebraic reconstruction of F. de Saussure; behind the totality of correspondences, the position of the reconstructive model should be preserved.

3) What and how can and should be compared in the comparative historical study of languages?

A) It is necessary to compare words, but not only words and not all words, and not by their random consonances.

The “coincidence” of words in different languages with the same or similar sound and meaning cannot prove anything, since, firstly, this may be a consequence of borrowing (for example, the presence of the word factory in the form fabrique, Fabrik, fabriq, factories, fabrika and etc. in a variety of languages) or the result of a random coincidence: “so, in English and in New Persian the same combination of articulations bad means “bad,” and yet the Persian word has nothing in common with English: it is pure “ game of nature." "Cumulative consideration English vocabulary and New Persian vocabulary shows that no conclusions can be drawn from this fact.”1

B) You can and should take words from the languages being compared, but only those that can historically relate to the era of the “base language”. Since the existence of a base language should be assumed in a communal-tribal system, it is clear that the artificially created word of the era of capitalism, factory, is not suitable for this. What words are suitable for such a comparison? First of all, the names of kinship, these words in that distant era were the most important for determining the structure of society, some of them have survived to this day as elements of the main vocabulary of related languages (mother, brother, sister), some have already “went into circulation” i.e., it switched to a passive vocabulary (brother-in-law, daughter-in-law, yatras), but for comparative analysis both words are suitable; for example, yatra, or yatrov - “brother-in-law’s wife” - a word that has parallels in Old Church Slavonic, Serbian, Slovenian, Czech and Polish, where jetrew and the earlier jetry show a nasal vowel, which connects this root with the words womb, inside, inside -[ness], with French entrailles, etc.

Numerals (up to ten), some native pronouns, words denoting parts of the body, and then the names of some animals, plants, and tools are also suitable for comparison, but here there may be significant differences between languages, since during migrations and communication with other peoples, only words could be lost, others could be replaced by others (for example, a horse instead of a knight), others could simply be borrowed.

4) “Coincidences” of the roots of words or even words alone are not enough to determine the relationship of languages; as already in the 18th century. wrote V. Jonze, “coincidences” are also necessary in the grammatical design of words. We are talking specifically about grammatical design, and not about the presence of the same or similar grammatical categories in languages. Thus, the category of verbal aspect is clearly expressed in Slavic languages and in some African languages; however, this is expressed materially (in the sense of grammatical methods and sound design) in completely different ways. Therefore, based on this “coincidence” between these languages, there can be no talk of kinship.

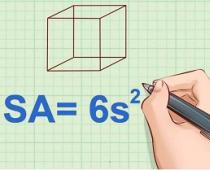

But if the same grammatical meanings are expressed in languages in the same way and in the corresponding sound design, then this indicates more than anything about the relationship of these languages, for example:

Where not only the roots, but also the grammatical inflections -ut, -zht, -anti, -onti, -unt, -and exactly correspond to each other and go back to one common source [although the meaning of this word in other languages differs from Slavic - “ carry"]. In Latin, this word corresponds to vulpes - “fox”; lupus – “wolf” – borrowed from the Oscan language.

The importance of the criterion of grammatical correspondence lies in the fact that if words can be borrowed (which happens most often), sometimes grammatical models of words (associated with certain derivational affixes), then inflectional forms, as a rule, cannot be borrowed. Therefore, a comparative comparison of case and verbal-personal inflections most likely leads to the desired result.

5) When comparing languages, it is very important role plays the sound design of the one being compared. Without comparative phonetics there can be no comparative linguistics. As already indicated above, the complete sound coincidence of the forms of words different languages can't show or prove anything. On the contrary, partial coincidence of sounds and partial divergence, provided there are regular sound correspondences, may be the most reliable criterion for the relationship of languages. When comparing the Latin form ferunt and the Russian take, at first glance it is difficult to detect a commonality. But if we are convinced that the initial Slavic b in Latin regularly corresponds to f (brother - frater, bean - faba, take -ferunt, etc.), then the sound correspondence of the initial Latin f to the Slavic b becomes clear. As for inflections, the correspondence of Russian u before a consonant with Old Slavic and Old Russian zh (i.e., nasal o) has already been indicated in the presence of vowel + nasal consonant + consonant combinations in other Indo-European languages (or at the end of a word), since such combinations in these languages, nasal vowels were not given, but were preserved as -unt, -ont(i), -and, etc.

The establishment of regular “sound correspondences” is one of the first rules of the comparative-historical methodology for studying related languages.

6) As for the meanings of the words being compared, they also do not necessarily have to coincide completely, but can diverge according to the laws of polysemy.

So, in Slavic languages city, city, grod, etc. mean “ locality of a certain type,” and shore, bridge, brig, brzeg, breg, etc. mean “shore,” but the words Garten and Berg (in German) corresponding to them in other related languages mean “garden” and “mountain.” It is not difficult to guess how *gord - originally a “fenced place” could get the meaning of “garden”, and *berg could get the meaning of any “shore” with or without a mountain, or, conversely, the meaning of any “mountain” near water or without it . It happens that the meaning of the same words does not change when related languages diverge (cf. Russian beard and the corresponding German Bart - “beard” or Russian head and the corresponding Lithuanian galva - “head”, etc.).

7) When establishing sound correspondences, it is necessary to take into account historical sound changes, which, due to the internal laws of development of each language, manifest themselves in the latter in the form of “phonetic laws” (see Chapter VII, § 85).

So, it is very tempting to compare Russian word gat and Norwegian gate – “street”. However, this comparison does not give anything, as B. A. Serebrennikov correctly notes, since in Germanic languages (to which Norwegian belongs) voiced plosives (b, d, g) cannot be primary due to the “movement of consonants,” i.e. historically valid phonetic law. On the contrary, at first glance, such difficultly comparable words as the Russian wife and the Norwegian kona can easily be brought into correspondence if you know that in Scandinavian Germanic languages [k] comes from [g], and in Slavic [g] in the position before vowels the front row changed to [zh], thereby the Norwegian kona and the Russian wife go back to the same word; Wed Greek gyne - “woman”, where there was neither movement of consonants, as in Germanic, nor “palatalization” of [g] in [zh] before front vowels, as in Slavic.

If we know the phonetic laws of development of these languages, then we cannot be “scared” by such comparisons as the Russian I and the Scandinavian ik or the Russian hundred and the Greek hekaton.

8) How is the reconstruction of the archetype, or primordial form, carried out in the comparative historical analysis of languages?

To do this you need:

A) Compare both root and affix elements of words.

B) Compare data from written monuments of dead languages with data from living languages and dialects (testament of A. Kh. Vostokov).

C) Make comparisons using the “expanding circles” method, i.e., going from comparing the closest related languages to the kinship of groups and families (for example, compare Russian with Ukrainian, East Slavic languages with other Slavic groups, Slavic with Baltic, Balto-Slavic – with other Indo-European ones (testament of R. Rusk).

D) If we observe in closely related languages, for example, such a correspondence as Russian - head, Bulgarian - head, Polish - glowa (which is supported by other similar cases, such as gold, zlato, zloto, as well as vorona, vrana, wrona, and other regular correspondences), then the question arises: what form did the archetype (protoform) of these words of related languages have? Hardly any of the above: these phenomena are parallel, not ascending to each other. The key to solving this issue lies, firstly, in comparison with other “circles” of related languages, for example with Lithuanian galvd - “head”, with German gold - “golden” or again with Lithuanian arn - “crow”, and in -secondly, in bringing this sound change (the fate of the groups *tolt, tort in Slavic languages) under more common law, in this case under the “law of open syllables”1, according to which in Slavic languages the sound groups o, e before [l], [r] between consonants had to give either “full consonance” (two vowels around or [r], as in Russian), or metathesis (as in Polish), or metathesis with vowel lengthening (from where o > a, as in Bulgarian).

9) In the comparative historical study of languages, it is necessary to highlight borrowings. On the one hand, they do not provide anything comparative (see above about the word factory); on the other hand, borrowings, while remaining in an unchanged phonetic form in the borrowing language, can preserve the archetype or generally more ancient appearance of these roots and words, since those phonetic changes, which are characteristic of the language from which the borrowing occurred. So, for example, the full-vowel Russian word tolokno and the word that reflects the result of the disappearance of the former nasal vowels, kudel, are available in the form of ancient borrowings talkkuna and kuontalo in Finnish, where the appearance of these words is preserved, closer to archetypes. Hungarian szalma - “straw” indicates ancient connections between the Ugrians (Hungarians) and Eastern Slavs in the era before the formation of full-vowel combinations in the East Slavic languages and confirms the reconstruction of the Russian word straw in Common Slavic as *solma1.

10) Without the correct reconstruction technique, it is impossible to establish reliable etymologies. On the difficulties of establishing the correct etymology and the role of comparative historical study of languages and reconstruction, in particular in etymological studies, see the analysis of the etymology of the word millet in the course “Introduction to Linguistics” by L. A. Bulakhovsky (1953, p. 166).

The results of almost two centuries of research into languages using the method of comparative historical linguistics are summarized in a scheme for the genealogical classification of languages.

It has already been said above about the unevenness of knowledge about the languages of different families. Therefore, some families, more studied, are presented in more detail, while other families, less known, are given in the form of drier lists.

Families of languages are divided into branches, groups, subgroups, and sub-subgroups of related languages. Each stage of fragmentation unites languages that are closer than the previous, more general one. Thus, East Slavic languages show greater closeness than Slavic languages in general, and Slavic languages show greater closeness than Indo-European languages.

When listing languages within a group and groups within a family, the living languages are listed first, and then the dead.

F. Bopp, R. Rusk, I

New ideas and a new method of processing them - all this led to the isolation of linguistics as a comparative historical science, which has its own philosophical foundations and research method. Comparative-historical linguistics studies related languages, their classification, history and distribution. With the increase in the volume of factual material - in addition to Greek and Latin, Germanic, Iranian and Slavic languages were studied and the question of the unity of linguistics was raised at the beginning of the 19th century. The philological study of Germanic languages, especially German and English, and comparative historical coverage of the structure of individual Germanic languages, and the Gothic language in particular, led to the emergence of Germanic studies at the beginning of the 19th century. Big role in the development of German studies, i.e. science studying comparatively historically Germanic languages was played by the works of learned linguists R. Rusk, J. Grimm and F. Bopp.

Rusk's main works: “A Study of the Origin of the Old Norse or Icelandic Language”, “On the Fractic Group of Languages” and Grimm’s “German Grammar” analyze the comparative historical method in Indo-European linguistics. Rusk and Grimm established two laws for the movement of consonants in Germanic languages. In the field of morphology, strong verbs are recognized as older than weak ones, and internal inflection is older than external ones. In the works “The conjugation system in Sanskrit in comparison with Greek, Latin, Persian and Germanic languages” and “Comparative grammar of Sanskrit, Zenda, Greek, Latin, Gothic and German languages“F. Bopp, taking Sanskrit as a basis for comparison, discovered the similarity of morphology and regularity of phonetic correspondences of a large group of languages, which he called Indo-European - Sanskrit and Zenda, Armenian, Ancient Greek, Latin, Gothic, Old Church Slavonic and Lithuanian. He created a comparative grammar of Indo-European languages. The kinship of Indo-European languages has been proven, and comparatively - historical method has been established as one of the main methods of language learning.

Rask: Rasmus Christian is a Danish linguist and Orientalist, one of the founders of Indo-European studies and comparative historical linguistics. Works in the field of German studies, Baltic studies, Iranian studies, African studies, Assyriology.

- · the hypothesis that the common structure of languages indicates a common origin;

- · comparison is important, first of all, the similarity of grammatical schemes: the number of types of declension and conjugation, the presence of strong and weak varieties, the grounds for their opposition;

- · discovered regular “letter transitions”, the commonality of basic vocabulary (especially numbers and places).

Jacob Grimm - German philologist, brother of Wilhelm Grimm, writer, librarian

- · studied etymology, discovered strict phonetic correspondences and umlaut (change of a vowel under the influence of a suffix);

- · In 1819, “German Grammar” was published, the purpose of which was to prove the close relationship of the Germanic languages.

Franz Bopp - German linguist, founder of comparative linguistics

- · task: rationalistically explain the formation of an inflectional structure that is the result of the integration of previously independent linguistic units;

- · the verb always has the structure “esse”; a noun is the result of agglutination of small roots that previously had an independent content or formative meaning. Franz Bopp used a comparative method to study the conjugation of main verbs in Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and Gothic, comparing both roots and inflections. Using a large survey of material, Bopp proved the declarative thesis of W. Jones and in 1833 wrote the first “Comparative Grammar of the Indo-Germanic (Indo-European) Languages.”

The Danish scholar Rasmus-Christian Rask strongly emphasized that grammatical correspondences are much more important than lexical ones, because borrowing inflections, and in particular inflections, “never happens.” Rask compared the Icelandic language with Greenlandic, Basque, and Celtic languages and denied them kinship (regarding the Celtic Rask later changed his mind). Rusk then compared Icelandic with Norwegian, then with other Scandinavian languages (Swedish, Danish), then with other Germanic languages, and finally with Greek and Latin languages. Rusk did not bring Sanskrit into this circle. Perhaps in this respect he is inferior to Bopp. But the involvement of Slavic and especially Baltic languages significantly compensated for this deficiency.

Great achievements in clarifying and strengthening this method on a large comparative material of Indo-European languages belong to August-Friedrich Pott, who gave comparative etymological tables of Indo-European languages.

The results of almost two centuries of research into languages using the method of comparative historical linguistics are summarized in the scheme of the Genealogical Classification of Languages.

3. Kitama language tradition - a tradition of language learning that arose in China, one of the few independent traditions famous history world linguistics. Its methods are still used in the study of Chinese and related languages. The study of language began in China over 2000 years ago and until the end of the 19th century. developed completely independently, apart from some influence of Indian science. Chinese classical linguistics is interesting because it is the only one that arose on the basis of a language of a non-inflective type, moreover, written in ideographic writing. Chinese is a syllabic language; a morpheme or a simple (root) word in it, as a rule, is monosyllabic, the phonetic boundaries of syllables coincide with the boundaries of grammatical units - words or morphemes. Each morpheme (or simple word) is indicated in writing by one hieroglyph. The hieroglyph, the morpheme it denotes, and the syllable constitute, in the view of the Chinese linguistic tradition, a single complex, which was the main object of study; the meaning and reading of the hieroglyph were the subject of the two most developed branches of Chinese linguistics - lexicology and phonetics. The oldest branch of linguistics in China was the interpretation of the meanings of words or hieroglyphs. The first dictionary -- "-- is a systematic collection of interpretations of words found in ancient written monuments. It does not belong to one author and was compiled by several generations of scientists, mainly in the 3rd and 2nd centuries. BC e. Around the beginning of AD e. "Fan Yan" ыЊѕ ("Local Words") appeared - a dictionary of dialect words attributed to Yang Xiong -g-Y. The most important is the third most important dictionary - “(Interpretation of Letters) by Xu Shen ‹–ђT, completed in 121 AD. e. It contains all the hieroglyphs known to the author (about 10 thousand), and is probably the world's first complete explanatory dictionary any language. It not only indicates the meaning of hieroglyphs, but also explains their structure and origin. The classification of hieroglyphs into “six categories” () adopted by Xu Shen developed somewhat earlier, no later than the 1st century; it existed until the 20th century, although some categories in different time have been interpreted differently.

In the future, phonetics became the main direction in Chinese linguistics. Chinese writing does not allow writing units smaller than a syllable. This gives Chinese phonetics a very unique look: its content is not a description of sounds, but a classification of syllables. The Chinese knew the division of a syllable only into two parts - the initial (sheng gYa, initial consonant) and the final (yun ‰C, literally - rhyme, the rest of the syllable); The awareness of these units is evidenced by the presence of rhyme and alliteration in Chinese poetry. The third distinguished element of the syllable was a non-segmental unit - tone. At the end of the 2nd century. a way was invented to indicate the reading of a hieroglyph through readings of two others - the so-called cutting (the first sign denoted a syllable with the same initial, the second - with the same ending and tone as the reading of an unknown hieroglyph. For example, duвn "straight" is cut with the hieroglyphs duф 'S century, rhyming dictionaries built on a phonetic principle appeared. The earliest dictionary of this type that has come down to us. A big step forward was the creation of phonetic tables that make it possible to visually represent the phonological system. Chinese language and reflect all the phonological oppositions existing in it. In the tables, initials are located on one axis, finals on the other; at the intersection of the lines the corresponding syllable is inserted. For example, at the intersection of the line corresponding to the final -ы and the column corresponding to the initial g-, a hieroglyph with the reading gы is written. Each table is divided into four parts by four tones and includes several close-sounding finals, differing in the intermediate vowel or shades of the main vowel. The initials are combined into groups similar to Indian wargs (in which Indian influence can be seen). Systematization of syllables in tables required complex and branched terminology. The first phonetic tables - "Yun Jing" are known from the 1161 edition, but were compiled much earlier (possibly at the end of the 8th century).

In the 17th-18th centuries. Historical phonetics has achieved great success. The most famous works are by Gu Yanwu (1613-82) and Duan Yucai). Scientists working in this area sought to reconstruct the phonetic system of the ancient Chinese language based on the rhymes of ancient poetry and the structure of hieroglyphs of the so-called phonetic category. This was the first direction in world linguistic science that was entirely based on the principle of historicism and aimed at restoring the facts of the past state of the language that were not directly reflected in written monuments. His methods and the results he achieved are also used by modern science.

Grammar was much less developed, which is due to the isolating nature of the Chinese language. The concept of a function word has been known since ancient times. In the 12th-13th centuries. a contrast appeared between “full words” (shi zi ›‰Ћљ) and “empty words” (xu zi?Ћљ); The “empty” ones included function words, pronouns, interjections, non-derivative adverbs and some other categories of words. The only type of grammatical work was dictionaries of “empty words”; the first appeared in 1592. Such dictionaries still exist. In the area of syntax, a distinction was made between a sentence (ju ‹le) and a syntactic group (dou zh¤).

The isolated position of Chinese linguistics ended in recent years 19th century, with the advent of the first alphabetic writing projects for Chinese dialects and the first Chinese grammar Ma

Background and history:

Linguistic science dates back about 3 thousand years. In V. BC. first appeared scientific description ancient Indian literary language- Panini's grammar. At the same time, linguistics began to develop in Dr. Greece and other East - in Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt. But the most ancient linguistic ideas go back even further into the depths of centuries - they exist in myths, legends, tales. For example, the idea of the Word as a spiritual principle, which served as the basis for the origin and formation of the world.

The science of language began with the doctrine of correct reading and writing initially among the Greeks - “grammatical art” was included in a number of other verbal arts (rhetoric, logic, stylistics).

Linguistics is not only one of the most ancient, but also the main sciences in the knowledge system. Already in Dr. In Greece, the term “grammar” meant linguistics, which was considered the most important subject. Thus, Aristotle noted that the most important sciences are grammar, along with gymnastics and music. In his writings, Aristotle was the first to divide: letter, syllable and word; name and rheme, copula and member (in grammar); logos (at the sentence level).

Ancient grammar identified spoken and written speech. She was primarily interested in written language. Therefore, in antiquity written grammar was developed and dictionaries existed.

The importance of the science of language among the other Greeks stemmed from the peculiarities of their worldview, for which language was an organic part of the surrounding world.

In the Middle Ages, man was considered the center of the world. The essence of language was seen in the fact that it united the material and spiritual principles (its meaning).

During the Renaissance, the main question arises: the creation of a national literary language. But first it was necessary to create a grammar. The Port-Royal grammar, created in 1660 (named after the monastery), was popular. It was universal in nature. Its authors compared the general properties of different languages. In the 18th century, M.V.’s grammar was published. Lomonosov. The focus is on the teaching of parts of speech. Lomonosov connected grammar with stylistics (he wrote about norms and the variation of these norms). He drew attention to the fact that language develops along with society.

Many languages are similar to each other, so the scientist expressed the opinion that languages could be related. He compared the Slavic and Baltic languages and discovered similarities.

Lomonosov laid the foundations for the comparative historical study of languages. Has begun new stage studies – comparative historical.

The science of language is interested in language as such. The founders of the comparative historical method are considered to be F. Bopp, R. Rask, J. Grimm, A. Kh. Vostokov.

The end of the 18th - mid-19th centuries are associated in linguistics with the name of W. von Humboldt, who raised a number of fundamental questions: about the connection between language and society, about the systemic nature of language, about the symbolic nature of language, about the representation and problem of the connection between language and thinking. Later, they acquired special significance views on language I.A. Baudouin de Courtenay and F. de Saussure. The first distinguished between synchrony and diachrony, created the doctrine of material

side, identified units of language (phonemes) and units of speech (sounds). He formulated and clarified the concepts of phonemes, morphemes, words, sentences and was one of the first to describe the sign nature of linguistic units. The second attributed linguistics to the field of psychology and called for studying only internal linguistics (language and speech). Saussure considered language a system of signs. He was the first to identify the objects of linguistics - language; system of signs; distinction between language and speech; study of the internal structure of language.

Structuralism appeared at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. Structuralists identified synchronous language learning as the leading one. Language structure – different elements enter into a relationship. Objectives: to find out to what extent a linguistic unit is identical to itself, what set of differentiated features a linguistic unit has; how a language unit depends on the language system as a whole and other language units in particular.

The essence of the concept of “linguistics”. Object and main problems of linguistic science:

Linguistics(linguistics, linguistics: from Latin lingua - language, i.e. literally the science that studies language) - the science of language, its nature and functions, its internal structure, patterns of development.

The theory of language (general linguistics) is, as it were, a philosophy of language, since it considers language as a means of communication, the connection between language and thinking, language and history. The object of linguistics is language in the entire scope of its properties and functions, structure, functioning and historical development.

The range of problems of linguistics is quite wide - this is the study of: 1) the essence and nature of language; 2) structures and internal connections language; 3) historical development of the language; 4) functions of language; 5) iconicity of the language; 6) linguistic universals; 7) methods of language learning.

You can select three main tasks facing linguistics:

1) establishment of typical features found in various languages of the world;

2) identification of universal patterns of language organization in semantics and syntax;

3) development of a theory applicable to explain the specificity and similarities of many languages.

Thus, linguistics as academic discipline provides basic information about the origin and essence of language, the features of its structure and functioning, the specifics of linguistic units at different levels, and speech as an instrument effective communication and norms of speech communication.

Sections of linguistics:

Today it is customary to distinguish between linguistics: a) general and specific, b) internal and external, c) theoretical and applied, d) synchronous and diachronic.

In linguistics there is a distinction public and private sections. The largest section of the theory of language—general linguistics—studies the general properties, features, and qualities of human language in general (identifying linguistic universals). Particular linguistics studies each individual language as a special, unique phenomenon.

In modern linguistics, it is common to divide linguistics into internal and external. This division is based on two main aspects in the study of language: internal, aimed at studying the structure of language as an independent phenomenon, and external (extralinguistic), the essence of which is the study of external conditions and factors in the development and functioning of language. Those. internal linguistics defines its task as the study of the systemic-structural structure of language, external linguistics deals with the study of problems of the social nature of language.

Theoretical linguistics– scientific, theoretical study language, summarizing data about the language; serves methodological basis for practical (applied) linguistics.

Applied linguistics– practical use of linguistics in various fields of human activity (for example, lexicography, computing, teaching methods foreign languages, speech therapy).

Depending on the approach to language learning, linguistics can be synchronous ( from ancient Greek syn - together and chronos - time relating to one time), describing the facts of a language at any point in its history (usually the facts of a modern language), or diachronic, or historical (from the Greek dia - through, through), tracing the development of language over a certain period of time. It is necessary to strictly distinguish between these two approaches when describing the language system.

The prerequisites for the occurrence will comparehistorical-historical linguistics

(պատմահամեմատական լեզվաբանության ծագման նախադրյալները)

Antiquity was not interested in the question of the diversity of languages, since the Greeks and Romans recognized only their own language as worthy of study, while they considered other languages “barbaric,” equating other people’s speech to inarticulate “muttering.”

In the Middle Ages, the issue of the diversity of languages was resolved in accordance with the Bible: the diversity of languages was explained by the legend of the Tower of Babel, according to which God “mixed” the languages of the people who built this tower to prevent them from entering heaven.

Only during the Renaissance, when the need arose to theoretically comprehend the question of the composition and type of the national language, the exponent of a new culture, and its relationship with Latin and Ancient Greek, did scientists think about solving this issue in a scientific way.

So, the prerequisites for the emergence of comparative historical linguistics are divided into 1) extralinguistic (extralinguistic) and 2) linguistic.

1) The first ones include geographical discoveries, who introduced into the scope of research numerous languages previously unknown to science: Asian, African, American, and then Australian and Polynesian. The discovery of new lands and peoples soon leads to their conquest by technically advanced European states and to the beginning colonial expansion(??? The need that arose in connection with this to communicate with the natives and influence them through religion leads to dissemination among them Christianity. It was the missionary monks who owned the earliest dictionaries (glossaries) and grammatical descriptions of various languages of the world (the so-called missionary grammars).

2) Thus, we moved on to one of the linguistic prerequisites for the emergence of comparative historical linguistics - to the fact of the creation multilingual dictionaries and comparative grammars. This phenomenon soon becomes widespread, and sometimes even on a national scale. So, at the end of the 18th century. in Russia, with the assistance of Catherine II, lists of words and instructions were prepared, which were sent to the administrative centers of Siberia to the members of the Academy who worked there, as well as to various countries where Russia had its representative offices (ներկայացուցչություններ), for collecting data lists of words corresponding equivalents (րժեք բառեր) from local languages and adverbs. The materials of this study were processed by Acad. P.S. Pallas and summarized by him in a large translation and comparative dictionary, published in 1786-1787. (Ist two-volume edition). This was the first dictionary of this type, published under the title “Comparative Dictionaries of All Languages and Adverbs,” where a “Catalog of Languages” was collected for almost 200 languages of Europe and Asia. In 1790-1791 a second (expanded and corrected) four-volume edition of this dictionary was released with the addition of data on 30 languages of Africa and 23 languages of America (272 languages in total).

A second similar dictionary was carried out by a Spanish monk named Lorenzo Hervas y Panduro, who first in Italian (1784) and then in Spanish (1800-1805) published a dictionary entitled “Catalog of the languages of known peoples, their calculation, division and classification according to the differences of their dialects and dialects,” in which gave information about approximately 300 languages, not limiting himself only to vocabulary material, but also giving a brief grammatical description of them (for 40 languages).

The most famous dictionary of this type is “Mithridates, or General Linguistics” by the Baltic Germans I. Kh. Adelunga and I.S. Vatera(1806-1817, four volumes), which contains the prayer “Our Father” in 500 languages of the world, and for most languages it is a fantastic artificial translation. True, this edition contains comments on the translation and some grammatical and other information, in particular W. Humboldt’s note on the Basque language.

All these attempts at “cataloging languages,” no matter how naive they were, nevertheless brought great benefits: they introduced real facts the diversity of languages and the possibilities of similarities and differences between languages within the same words, which enriched factual knowledge of languages and promoted interest in the comparative comparison of languages.

And yet, although the ground was ready for the emergence of comparative historical linguistics, one more, final push was needed, which would suggest the correct ways to compare languages and indicate the necessary goals of such research. And such a “push” became opening Sanskrit 1 is apparently the most important linguistic factor that directly influenced the emergence of comparative historical linguistics.

The first person to notice the similarities between Sanskrit and European languages was the Florentine merchant and traveler Filippo Sassetti(1540–1588). Comparing Italian words such as sette(seven), nove(nine), Dio(God) with Sanskrit sapta, nava, devas, he realized that their similarity was not accidental, but due to linguistic kinship. He reported this in his “Letters from India”, but no scientific conclusions were drawn from these publications.

The question was correctly posed only in the second half of the 18th century, when the Institute of Oriental Cultures was established in Calcutta. In 1786, the English orientalist and lawyer William Jones in a paper read to the Asiatic Society in Calcutta, pointed out the connection of Sanskrit with Greek, Latin, Celtic, Gothic and Old Persian and the regular coincidences between the various forms of these languages. Jones's conclusion is that the following points: 1) similarity not only in roots, but also in grammatical forms cannot be the result of chance; 2) there is a kinship of languages that go back to one common and, perhaps, 3) no longer existing source, 4) to which, in addition to Sanskrit, Greek and Latin, Germanic, Celtic and Iranian languages also go back. Of course, in Jones we do not yet find any strictly formulated method of linguistic analysis and proof, and, moreover, Sanskrit for him does not act as a proto-language, as was typical for later theories. At the same time, Jones declared that Sanskrit has an amazing structure, more perfect than Greek, richer than Latin, and more beautiful than each of them.

However, the list of factors that led to the emergence of comparative historical linguistics will be incomplete if we do not point out two more - a) development romantic direction and - most importantly - b) penetration into science and universal recognition the principle of historicism. These factors (also of an extralinguistic nature) can be called philosophical and methodological prerequisites for comparative historical linguistics. If romanticism led to interest in the national past and contributed to the study of ancient periods of the development of living languages, then the principle of historicism, which penetrated into linguistics, was embodied in it in the method of comparing languages from a historical angle and classifying languages taking into account their origin and development.

Questions and assignments on the covered topic:

List the main extralinguistic prerequisites for the emergence of comparative historical linguistics (CHL).

What are the linguistic prerequisites of SFL?

Why not in ancient times, neither in the Middle Ages did scientists address the issue of the diversity of languages?

What is the merit of P.S.

Pallas and L. Hervas y Panduro in the comparative study of languages?

Name and describe the work of I. H. Adelung and I. S. Vater.

Briefly list the conclusions of W. Jones. 2 first attempts at genealogy

language classifications For the first time, the idea of genetic connections between languages, i.e. The idea of the kinship of languages arose long before the emergence of comparative historical linguistics. Back in 1538, the work of the French humanist Guilelme Postellus “On the kinship of languages” appeared - the first attempt to classify (դասակարգում) languages. And already in 1599, the Dutch scientist Joseph-Justus in the treatise “Discourse on the Languages of Europeans” he makes an attempt to classify European languages, reducing them to 11 main groups, among which he distinguishes 4 large and 7 small. According to Scaliger, each group had its own “mother language,” and the unity of the language is manifested in the identity of words. The names of the 4 “big” mother languages - Latin, Greek, Teutonic (Germanic) and Slavic - are conveyed by Scaliger accordingly in the words Deus, Θεòς, Godt, God. The seven minor mother languages are Albanian, Tatar, Hungarian, Finnish, Irish, Cymric (British) and Basque. Moreover, all 11 “mother languages” are “not related to each other by ties of kinship.”

The problem of the relationship of languages also worried philosophers during this period. Gottfried-Wilhelm pays a lot of attention to this issue Leibniz, who divided the languages known to him into two main groups: 1) Aramaic (Semitic); 2) Japhetic. He divides the last group into two more subgroups: a) Scythian (Finnish, Turkic, Mongolian, Slavic) and b) Celtic (European). If in this classification we move the Slavic languages into the “European” subgroup, and rename the “Scythian” ones at least “Ural-Altaic”, then we will practically get what linguists came to in the 19th century.

In the 18th century Dutch explorer Lambert Ten-Kate in the book “Introduction to the Study of the Noble Part of the Low German Language,” he made a thorough comparison of the Germanic languages (Gothic, German, Dutch, Anglo-Saxon and Icelandic) and established the most important sound correspondences of these related languages.

Of great importance among the predecessors of comparative historical linguistics are the works of M.V. Lomonosov: “Russian Grammar” (1755), Preface “On the Use of Church Books in the Russian Language” (1757 / 1758) and the unfinished work “On languages related to Russian and on current dialects”, which gives a precise classification of the three groups of Slavic languages indicating the greater proximity of the eastern to the southern than to the western (n/r, Russian is closer to Bulgarian than to Polish), correct etymological (ստուգաբանական) correspondences of single-root Slavic and Greek words are shown on a number of words. He also establishes the family relations of the Slavic languages with other Indo-European languages, namely with the Baltic, Germanic, Greek and Latin, and notes a particularly close connection between the Slavic languages and the Baltic. Lomnosov most often compares languages based on the analysis of numerals.

However, the works of these scientists, created without any genuine historical theory, could not lead to the desired results; they were only at the origins of comparative historical linguistics. In addition, the colossal comparative lexicographical work that was carried out at the turn of the 18th – 19th centuries has not yet been carried out. in different countries of Europe and Asia. This is on the one hand. And on the other hand - scientific world I still knew nothing about Sanskrit - the literary language of ancient India and about its unique, exceptional role in the study of Indo-European languages. Textbook

... linguistics, literary studies). However, after 1917 it developed in new social historical ... , compared niya... historical In relation to fairy tales, they are a rather late phenomenon. Prerequisite ... spruce forest... _ origin, emergence; education process...

Textbook for students of non-historical specialties

DocumentSocieties - with emergence property inequality... 5) the interest of the church. Prerequisites associations were: a) ... It can be compare with that... to independent historical creativity, ... under Yelney(here... political economy and linguistics. Victims...

Language is the most important means of human communication. There are thousands of different languages around the globe. But since the differences between them and dialects of the same language are often very vague and arbitrary, scientists do not give the exact number of languages in the world, defining it approximately from 2500 to 5000.

Each language has its own specific features that distinguish it from other languages. At the same time, in its main features, all the languages of the world have much in common with each other, which gives scientists reason to talk about human language in general.

People have long been interested in language and over time created a science about it, which is called linguistics or linguistics (from the Latin Lingua - language).

Linguistics and young and old science. It is young in the sense that only in the first quarter of the 19th century was it “officially” separated from other sciences - philosophy and philology. But it is also an old science, since the study of individual languages and their scientific description goes back to the distant past - to the first centuries BC.

That is why it is necessary to reject as an erroneous point of view of some linguists that the science of language supposedly begins counting its time only from the first quarter of the 19th century - the time of the formation of comparative historical linguistics. As for the entire previous period of language learning, it should supposedly be considered pre-scientific.

The 19th century was indeed a turning point in the development of linguistics, since scientists for the first time managed to pose and substantiate, using sufficient linguistic material, the problem of the kinship of languages, the origin of individual groups of languages from a common source, to which the name was assigned proto-language.

The foundations of comparative historical linguistics based on the languages of the Indo-European area were laid by German scientists Franz Bopp (1791-1867), Jacob Grimm (1785-1863), Danish linguist Rusmus Rask (1787-1832) and Russian philologist academician of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences Alexander Khristoforovich Vostokov (1781 -1864).

The works of the outstanding German encyclopedist Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835) laid the foundations of general theoretical linguistics, the intensive period of development of which began in the mid-19th century.

Let us clarify that in our time there is increasing recognition of the point of view according to which the first attempts that laid the foundation for the emergence of general linguistics were made back in the 17th century by French scientists Antoine Arnauld (1612-1694) and Claude Lanslot (1616-1695), who published the fundamental treatise entitled "General and Rational Grammar of Port Royale".

And yet, the cradle of linguistics should be considered not Europe, but ancient India, because interest in learning the language originated in this country with its ancient original culture and philosophy. The most famous work of that time was the grammar of classical Sanskrit, the literary language of the ancient Indians, written in the 4th century BC. scientists Pbnini. This work of the Indian researcher continues to delight scientists today. So, A.I. Thomson (1860-1935) rightly notes that “the height that linguistics has reached among the Indians is absolutely exceptional, and the science of language in Europe could not rise to this height until the 19th century, and even then having learned a lot from the Indians.”

Indeed, the works of Indians on language had a great influence on neighboring peoples. Over time, the linguistic ideas of the Indians and the method they carefully developed for a synchronic approach to describing the linguistic structure of a single language, especially at the level of phonetics and morphology, crossed the borders of India and began to penetrate first into China, ancient Greece, then into Arab countries, and from the end of the 18th century , when the British became acquainted with Sanskrit - and to Europe. It was the acquaintance of Europeans with Sanskrit that was the impetus for the development of comparative historical issues.

The scientist who discovered Sanskrit for Europeans was the English orientalist and lawyer William Jonze (1746-1794), who was able to write, having familiarized himself with Sanskrit and some of the modern Indian languages, enthusiastic words about the ancient Indian literary language: “The Sanskrit language, whatever its antiquity, has a wonderful structure, more perfect than the Greek, richer than the Latin, and more beautiful than either of them, but bearing in itself such a close affinity with these two languages, both in the roots of the verbs and in the forms of the grammar , which could not have been generated by chance, the kinship is so strong that no philologist who would study these three languages could fail to believe that they all originated from one common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists. .

The scientific research of F. Bopp and J. Grimm fully confirmed the validity of this short, abstract in form, but deep in content characteristics of the close relationship of Sanskrit with two classical languages of the distant past and served as an incentive to develop the basic principles of a new method in linguistics - comparative-historical.

But considering that already within the framework of the ancient Indian, classical, Chinese, as well as Arab, Turkic and European (until the 19th century) linguistic traditions, such topical problems as the nature and origin of language, the relationship of logical and grammatical categories, the establishment of sentence members and the composition of parts of speech, and many others, the entire more than two thousand-year period preceding the stage of formation and development of comparative historical linguistics must be considered an integral, organic part of linguistics as a science.

- In contact with 0

- Google+ 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0