A good owner is not out of a sense of self-interest, but out of a sense of duty

I have already had several occasions to speak about the remarkable and noble personality of Emperor Alexander III. It is a great misfortune that he reigned so little: only 13 years; but even in these 13 years, his figure, as the Emperor, completely took shape and grew. This was felt by all of Russia and all abroad on the day of his death. But Emperor Alexander III was far from appreciated by his contemporaries and the next generation, and the majority are skeptical about His reign. It's in high degree not fair.<….>I said he was a good host; Emperor Alexander III was a good host, not because of a sense of self-interest, but because of a sense of duty. Not only in the royal family, but also among dignitaries, I never met that feeling of respect for the state ruble, for the state penny, which Emperor Alexander III possessed. He saved every penny of the Russian people, the Russian state, as the best owner could not protect it.

Being under him for two years as the Minister of Finance and, finally, knowing his attitude to finance, even when I was the director of the department of the Ministry of Finance - I must say that it was thanks to Emperor Alexander III, Vyshnegradsky, and then, in the end, to me - managed to put the finances in order; for, of course, neither I nor Vyshnegradsky could have restrained all the impulses to throw right and left the money obtained by the blood and sweat of the Russian people in vain, if it were not for the mighty word of Emperor Alexander III, who held back all the onslaught on the state treasury. In the sense of the state treasurer, one can say that Emperor Alexander III was an ideal state treasurer - and in this respect facilitated the task of the Minister of Finance.

Just as he treated the money of the state budget, he treated his own household in the same way. He hated too much luxury, he hated too much throwing money; lived with remarkable modesty. Of course, under the conditions in which the Emperor had to live, his savings were often quite naive. So, for example, I cannot but say that in His reign, when I was a minister, the food at the court was comparatively very bad. I did not have the opportunity to often visit the Emperor's table, but as for the so-called chamber marshal's table, the food was so fed at this table that one can say that almost always, when one had to eat there, there was a danger to the stomach.<….>The following fact shows how Emperor Alexander III treated the war. I remember that once, in connection with some report - almost concerning the border guards, our conversation turned to the war. And this is what Emperor Alexander III told me:

I am glad that I was in the war and saw for myself all the horrors inevitably associated with the war, and after that, I think that every person with a heart cannot desire war, and every ruler to whom the people are entrusted by God must take all measures to ensure that in order to avoid the horrors of war, of course, if he (the ruler) is not forced into war by his opponents - then sin, curses and all the consequences of this war - let them fall on the heads of those who caused this war.

With Emperor Alexander III, every word was not an empty phrase, as we often see among rulers: very often rulers speak on one occasion or another beautiful phrases which are then forgotten after half an hour. With Emperor Alexander III, words never went wrong with deeds. What he said was felt by him, and he never deviated from what he said.

Thus, generally speaking, Emperor Alexander III, having received Russia, in the face of the most unfavorable political conjunctures, deeply raised the international prestige of Russia without shedding a drop of Russian blood.

We can say that at the end of his reign, Emperor Alexander III was the main factor in world international politics.

Average mind and beautiful heart

I had the good fortune to be close to two Emperors: to Emperor Alexander III and to the current reigning Emperor Nicholas II; I knew both very well.

Emperor Alexander III was undoubtedly of an ordinary mind, and of absolutely ordinary abilities, and, in this respect, Emperor Nicholas II stands much higher than his Father, both in mind and ability, and in education. As you know, Alexander III was not at all prepared to be Emperor. His elder brother Nikolai Alexandrovich, who already quite an adult died of consumption in Nice, focused on himself the attention of his father, Emperor Alexander II, and Empress Maria Alexandrovna; as for the future Emperor Alexander III, it can be said that He was somewhat in the pen; no special attention was paid to either His education or His upbringing, since, as I said, all the attention of both father and mother, and everyone around was focused on the Heir Nicholas, who, in his appearance, in his abilities and brilliance, who he showed - was incomparably higher than his brother Alexander.

And one, perhaps, Nikolai Alexandrovich at that time appreciated and understood his brother, the future Emperor Alexander III. From reliable sources it is known that when Tsarevich Nikolai was hopelessly ill (which he himself knew), then to the exclamation of one of those close to him: “What will happen if something happens to you? Who will rule Russia? After all, your brother Alexander is not at all prepared for this? - he said: “You don’t know my brother, Alexander: his heart and character completely replace and even exceed all other abilities that a person can be instilled in.”

And, indeed, Emperor Alexander III was of a completely ordinary mind, perhaps, one might say, below the average mind, below the average abilities and below the average education; in appearance - he looked like a big Russian peasant from the central provinces, a suit would suit him best of all: a short fur coat, undercoat and bast shoes - and nevertheless, he was his appearance, which reflected his enormous character, beautiful heart, complacency, justice and, at the same time, firmness - undoubtedly impressed and, as I said above, if they did not know that he was the Emperor, and he would enter the room in any suit - undoubtedly everyone would pay attention to him.

Therefore, I am not surprised by the remark that I myself remember hearing from Emperor Wilhelm II, namely, that he envies the kingship, the autocratic kingship, which manifested itself in the figure of Alexander III.

When I had to accompany the train of Emperor Alexander III, then, of course, I did not sleep day or night; and I constantly had to see that when everyone had already gone to bed, the valet of Emperor Alexander III, Kotov, was constantly darning his pants, because they were torn from Him. Once, passing by the valet (who is still alive and now is the valet of Emperor Nicholas II) and seeing that he is still darning his pants, I say to him:

Tell me, please, that you all darn your pants? Can't you take several pairs of trousers with you, so that if there is a hole in your trousers, you can give the Emperor new trousers? And he says:

Try to give, just He will put it on. If He, - he says, - puts on some pants or a frock coat, - then it's over, until the whole thing is torn at all seams - He will never throw it off. This is for Him - he says - the biggest trouble if you force Him to put on something new. Similarly, boots: give, - he says, Patent leather boots to Him, so He, he says, - will throw these boots out the window for you.

Only thanks to gigantic strength, he kept this roof

The third time I accompanied the imperial train was already at the end of the eighties, in the year of the collapse of the imperial train in Borki, near Kharkov. This crash took place in October during the return of the Sovereign from Yalta to Petersburg. - Earlier, in the month of August or July, the Sovereign, on his way to Yalta, made the following journey: He traveled by emergency train from St. Petersburg through Vilna to Rovno (then the Vilno-Rov. railroad had just been opened); from the station Rovno He has already gone along the South-West. well. d.; there I met him, and then the Emperor from Rovno (where the train did not stop) went through Fastov to Elisavetgrad. There the Sovereign made maneuvers to the troops; after these maneuvers, the Sovereign from Elisavetgrad returned to Fastov along the South-West. wish. dor. and, along the road, managed by me, I drove from Fastov to Kovel to Warsaw and Skiernievitsy (to one of the imperial palaces). After staying in Skiernevitsy for several weeks, the Emperor left Skiernievitsy again via Kovel and Fastov to the Crimea or the Caucasus (I don't remember). Then two months later he returned to St. Petersburg. And on the way back to Borki, this terrible incident happened with the imperial train.

Thus, in this year, during the summer and autumn, the Sovereign traveled 3 times through the South-West. wish. dor.

1st time - from Rivne to Fastov,

2nd time - from Fastov to Kovel and

3rd time - from Kovel again to Fastov.

So, when the imperial train arrived in Rovno, I, having met him, had to lead this train further.

The schedule of imperial trains was usually drawn up by the Ministry of Railways without any demand and participation of road managers. I received a timetable in time, according to which the train from Rovno to Fastov was supposed to travel such and such a number of hours, and in such a number of hours only a light, passenger train could cover this distance; meanwhile, a huge imperial train suddenly appeared in Rovno, made up of a mass of the heaviest wagons.

I was warned by telegram only a few hours before the arrival of this train in Rovno that the train would go with such a composition. Since such a train - and, moreover, at such a speed as was appointed - not only could not carry one passenger, but even two passenger locomotives, it was necessary to prepare 2 freight locomotives and carry it with two freight locomotives, that is, as they say, in a double carriage, because its weight was greater than the weight of an ordinary freight train, while the speed was set at the speed of passenger trains. Therefore, it was completely clear to me that some kind of misfortune could happen at any moment, because if freight locomotives go at such a speed, they completely loosen the path, and if in some place the path is not completely, not unconditionally strong, which always, on any track can and must happen, since nowhere, on any roads, is a track intended for such movement, at such a speed, with two freight locomotives, then these locomotives can turn the rails, as a result of which the train can crash. Therefore, I drove all the time, all night, as if in a fever, while everyone was sleeping, including the Minister of Railways (Admiral Posyet), who had his own carriage; the chief inspector of railways, engineer Baron Cherval, rode with him. I entered the carriage of the Minister of Railways and rode all the time; this car was completely behind, did not even have direct communication with other cars, so from there, from this car, it was not even possible to give any signal to the drivers. I was driving, I repeat, all the time in a fever, expecting that misfortune might happen at any moment.

And so, when we drove up to Fastov, I, giving the train to another road, could not have time to convey anything to either the Minister of Railways or Baron Cherval, because they had just woken up.

As a result, when I returned from Fastov to Kiev, I immediately wrote a report to the Minister of Railways, in which I explained how the movement along the road was carried out; that I did not have the courage to stop the train, because I did not want to create a scandal, but that I consider such a movement unthinkable, impossible ...

To this I received the following reply by telegram; that in view of my such a categorical statement, the Minister of Railways ordered the schedule to be redone and the train run time to be increased by three hours.

Then the day came when the Emperor had to go back. The train arrived (to Fastov) early in the morning; were still asleep, but soon woke up.

When I entered the station, I noticed that everyone was looking askance at me: the Minister of Railways was looking askance, and gr. Vorontsov-Dashkov, who rode this train, who was so close to my family and knew me from childhood, he also pretends that he does not know me at all.

Finally, Adjutant General Cherevin comes up to me and says: Sovereign Emperor ordered you to convey that He is very dissatisfied with the ride along the South-Western Railway. - Before Cherevin had time to tell me this, the Emperor himself came out, who heard Cherevin convey this to me. Then I tried to explain to Cherevin what I had already explained to the Minister of Railways. At this time, the Sovereign turns to me and says:

What are you saying. I drive on other roads, and no one slows me down, but you can’t drive on your road, simply because your road is Jewish.

(This is an allusion to the fact that the chairman of the board was the Jew Blioch.)

Of course, I did not answer the Emperor to these words, I remained silent. Then, immediately on this subject, the Minister of Railways entered into a conversation with me, who carried out the same idea as Emperor Alexander III. Of course, he did not say that the road was Jewish, but simply stated that this road was not in order, as a result of which it was impossible to go soon. And to prove the correctness of his opinion he says:

But on other roads we travel at such a speed, and no one has ever dared to demand that the Sovereign be taken at a lower speed.

Then I could not stand it and said to the Minister of Railways:

You know, Your Excellency, let others do as they please, but I don’t want to break the Sovereign’s head, because it will end with you breaking the Sovereign’s head in this way.

Emperor Alexander III heard this remark of mine, of course, was very dissatisfied with my insolence, but did not say anything, because He was a complacent, calm and noble person.

On the way back from Skierniewitz to Yalta, when the Sovereign again drove along our road, the train was already given that speed, they added the number of hours that I demanded. I again fit into the carriage of the Minister of Railways, and noticed that since the time I last saw this carriage; he leaned significantly to the left side. I looked up why this is happening. It turned out that this happened because the Minister of Railways, Admiral Posyet, had a passion for various, one might say, railway toys. So, for example, to furnaces of various heating and to various instruments for measuring speeds; all this was placed and attached to the left side of the car. Thus, the severity of the left side of the car increased significantly, and therefore the car tilted to the left side.

At the first station I stopped the train; the wagon was examined by specialists in car building, who found that it was necessary to watch the wagon, but that there was no danger, and the movement should continue. Everyone was asleep. I went further. Since each car has, so to speak, a list of the given car, in which all its malfunctions are recorded, I wrote in this car that I was warning: the car leaned to the left side; and this happened because all the instruments and so on. attached to the left side; that I did not stop the train, because the train was inspected by specialists who came to the conclusion that it could pass - those 600-700 miles that it had left to do along my road.

Then I wrote that if the car was at the tail, at the end of the train, then I think that it could pass safely to its destination, but that there it was necessary to carefully review it, remove all devices, it would be best to throw them away completely or transfer them to the other side. In any case, this wagon should not be placed at the head of the train, but placed at the tail.

Then I crossed myself and was glad that I got rid of these Royal trips, because great unrest, troubles and dangers were always associated with them.

It's been two months. Then I lived in Lipki opposite the house of the governor-general. There was a telegraph machine in one of the rooms, and since telegrams had to be given all day long, telegraph operators were on duty day and night.

Suddenly, one night, a valet knocks on my door. I woke up. They say there is an urgent telegram. I read: an urgent telegram signed by Baron Cherval, in which the baron telegraphs that the imperial train, traveling from Yalta, turned to the Sinelnikovo station along the Ekaterininsky road, and from there it will go to the Fastov station. From Fastov, the Emperor will go further along the South-Western road either through Kiev, or again through Brest, but rather through Kiev. Then I ordered to prepare an emergency train for myself to go to Fastov, and waited for me to be given a timetable when to go.

But before I left Kiev, I received a second telegram stating that the Sovereign would not go along the South-Western road, that, having reached the Kharkov-Nikolaev road, he turned to Kharkov and then he would go as expected: to Kursk and Moscow.

After receiving this telegram, I kept thinking: what happened there? Then there were vague rumors that the imperial train had been wrecked and the route had therefore changed. I imagined that in all probability something trifling had happened, as the train continued to move on.

Not even a few hours had passed before I received a telegram from Kharkov signed by Baron Cherval, in which he telegraphed me that the Minister of Railways suggested that I now come to Kharkov in order to be an expert on the cause of the collapse of the imperial train.

I went to Kharkov. Arriving there, I found Baron Cherval lying in bed at the Kharkov station, as his arm was broken; his courier also had a broken arm and leg (this same courier later, when I was Minister of Railways, was also my courier).

I arrived at the train wreck. In addition to me, the experts there were local railway engineers and then the director of the Technological Institute Kirpichev, who is still alive. The main role, of course, was played by me and Kirpichev. Kirpichev enjoyed and enjoys great prestige as a process engineer and as a professor of mechanics and railway construction in general, although he full sense words theorist and never served on the railways. In the examination, we parted ways.

It turned out that the imperial train was traveling from Yalta to Moscow, and they gave such a high speed, which was also required on the South-Western Railways. None of the road administrators had the courage to say that it was impossible. They also traveled in two steam locomotives, and the carriage of the Minister of Railways, although somewhat lightened by the removal of some devices from the left side, no serious repairs were made during the train's stop in Sevastopol; in addition, he was put at the head of the train. Thus, the train was moving at an inappropriate speed, two freight locomotives, and even with a not quite serviceable carriage of the Minister of Railways at the head. What happened was what I predicted: the train, due to the swing of a freight locomotive from a high speed, unusual for a freight locomotive, knocked out the rail. Commodity locomotives are not designed for high speed, and therefore, when a commodity locomotive goes at a speed that does not correspond to it, it sways; from this swing the rail was knocked out and the train crashed.

The entire train fell under the embankment and several people were crippled.

At the time of the crash, the Emperor and his family were in the dining car; the entire roof of the dining car fell on the Emperor, and he, only thanks to his gigantic strength, kept this roof on his back and it did not crush anyone. Then, with his characteristic calmness and gentleness, the Sovereign got out of the car, calmed everyone down and helped the wounded, and only thanks to his calmness, firmness and gentleness - this whole catastrophe was not accompanied by any dramatic adventures.

So, as an expert, I gave such a conclusion that the train crashed from the reasons I indicated. Kirpichev said that this catastrophe occurred because the sleepers were somewhat rotten. I examined the sleepers and came to the conclusion that Kirpichev did not know railway practice. On all Russian roads in wooden sleepers that have served for several months, the top layer is always somewhat rotten, it cannot be otherwise, because in any tree, if it is not constantly stained or pitched, it always top part(so-called apple tree) has a somewhat rotten layer; but the core, which holds the crutches that hold the rails to the sleeper - these parts of the sleepers were completely intact.

By the same time, my acquaintance with Koni, who was sent from St. Petersburg, to investigate this case, dates back. Then I met him for the first time. Apparently, Koni really wanted the road administration to be to blame for this catastrophe, so that the road administration was to blame, so he terribly disliked my expertise. He wanted the examination to establish that it was not the train department, not the inspector of the imperial trains, not the Minister of Railways that was to blame, but that the road administration was to blame. I gave the conclusion that only the central administration, the Ministry of Railways, was to blame, and the inspector of the imperial trains was also to blame.

The result of this catastrophe was the following: after some time, the Minister of Railways Posyet had to resign.

Baron Sherval also had to retire and settled in Finland. By origin, Baron Sherval was Finnish; he was a respectable man, very complacent, with a well-known Finnish dullness, and an engineer of medium caliber.

The emperor parted with these faces without any malice; these persons had to retire, due to the fact that public opinion in Russia was extremely indignant at what had happened. But Emperor Alexander III, not without reason, considered the engineer Salov, who at that time was the head of the railway department, to be the main culprit of the disaster. He was undoubtedly a smart, sensible and knowledgeable person, but practically knew little about the case. …

Emperor Alexander III, with his characteristic common sense, he took it apart, and therefore removed Salov of his own free will and not without a certain amount of natural malice.

CONSERVATIVES

Reforms 60-70 years. XIX century caused a wide public outcry. A significant part of Russian society believed that liberal reforms were undermining the foundations of the state and leading to social upheavals. The terrorist activities of the "populists" reinforced these conclusions. Tone to Russian conservatives second half of XIX century set two iconic figures of Russian social thought - M.N. Katkov and K.P. Pobedonostsev .

M.N. Katkov - a talented publicist and editor of the Moskovskie Vedomosti newspaper expressed his attitude to liberal ideas in the following way: “They say Russia is deprived of political freedom; they say that although Russian subjects are granted legal civil freedom, they do not have political rights. Russian subjects have something more than political rights; they have political responsibilities. Each of the Russians is obliged to stand guard over the rights of the Supreme Power and take care of the benefits of the state. Everyone not only has the right to take part in public life and take care of its benefits, but is also called to this by the duty of a loyal subject. Here is our constitution." The Polish uprising of 1863-1864 strengthened Katkov's conservative views even more, which made him a consistent fighter against Western European liberalism and radical movements. He was convinced of the possibility of reforming Russia without affecting the foundations of autocratic power, which, in his opinion, should have brought the country to the ranks of the leading Western European states. In this regard, he emphasized that the role of the nobility should not be leveled, which should remain in the new conditions the support of the throne and the link between the emperor and the people. That is why, being generally loyal to the introduction of zemstvos, he argued that the main role in them should be played by the nobility, supplemented by representatives from other estates. Also, in his opinion, zemstvo institutions had to be subordinated to the government, i.e. put them under the control of the bureaucracy. At the same time, he supported the judicial reform of 1864, arguing that "the court is an independent and wealthy force."

M.N. Katkov wrote a lot about the role of education and the need for such a reform of education that would bring up a generation confident in the inviolability of the state order and alien to the ideas of "nihilism". To do this, it was necessary to consistently implement the principles of the Uvarov doctrine - "Orthodoxy, autocracy, nationality."

It was in the person of Katkov that the government saw a publicist and publisher who could skillfully convey autocratic ideology to Russian society. Events of the 70s and early 80s. XIX century, in connection with the strengthening of the "populist" terror, M.N. Katkov was an even greater conservative, who sharply opposed not only the reforms, but also any manifestation of liberalism, even if it was moderate. And this activity has borne fruit. The opinion of Moskovskie Vedomosti was taken into account even in the government.

K.P. Pobedonostsev - the mentor of Alexander III, who in 1880 became the chief procurator of the Holy Synod, also played a significant role in determining the government course and its ideology, especially after the events of March 1, 1881. In the 60s of the XIX century, we see in him a consistent critic Emperor Alexander II, whom he accused of indecisiveness, irrational policy, and the lack of a consistent government course. He wrote: “Power is already becoming in Russia a toy that miserable and vulgar ambitious people want to pass on to each other through intrigue. There is no longer a firm center from which all power would directly emanate and on which it would be directly held. During the reforms of the 60-70s. he especially sharply opposed the radical implementation of judicial reform, criticized Milyutin's military reforms, especially the introduction of universal military service. “It's fun to say that a nobleman will be taken as a soldier as well as a peasant,” he said.

Having become a mentor to the heir to the throne, he consistently sought to protect him from the influence of supporters of liberal reforms, suggesting that "the whole secret of the Russian order and prosperity is at the top, in the person of the supreme power." And his influence on the new emperor was decisive. So, K.P. Pobedonostsev sharply opposed the Loris-Melikov project, which was discussed at a meeting of the Council of Ministers during March-April 1881. And it was under his influence that the famous manifesto of Alexander III was published on April 29, 1881, which proclaimed that the tsar would rule "with faith into the strength and truth of autocratic power”, which he will “assert and protect for the good of the people from any encroachments on it”. Thus, the adherents of conservatism won the government, which predetermined the whole course domestic policy Alexander III.

TSARISM AND THE WORKERS

Memoirs of G.V. Plekhanov

Written in the period of 1880-1890s, they tell about the life of an ordinary Russian worker in the 70s - early 80s of the last century

“It goes without saying that among the workers, as elsewhere, I met people who differed greatly among themselves in character, in abilities, and even in education.<…>But, in general, this whole environment was distinguished by significant mental development and high level their living needs. I was surprised to see that these workers live just as well, and many of them much better, than the students. On average, each of them earned 1 rub. 25 kopecks, up to 2 rubles. in a day. Of course, it was not easy for family people to exist on this relatively good income. But the unmarried - and they then made up the majority of the workers I knew - could spend twice as much as a poor student.<…>The more I got to know the Petersburg workers, the more I was struck by their culture. Lively and eloquent, able to stand up for themselves and be critical of their surroundings, they were city dwellers in the best sense of the word.<…>It must also be said that among the St. Petersburg workers, the "gray" village man was often a rather pathetic figure. A peasant from the Smolensk province S. entered the Vasileostrovsky Cartridge Plant as a lubricant. At this plant, the workers had their own consumer association and their own dining room, which at the same time served as a reading room, since it was supplied with almost all the capital's newspapers. It was in the midst of the Herzegovina uprising (it was about the uprising in Bosnia and Herzegovina against the Ottoman Empire in 1875. - Ed.). The new oiler went to eat in the common dining room, where the newspapers were read aloud at dinner, as usual. On that day, I don’t know in what newspaper, there was a talk about one of the “glorious defenders of Herzegovina”. The village man intervened in the conversation that arose on this subject and made an unexpected suggestion that "he must be her lover."

Who? Whose? asked the astonished interlocutors.

Yes, the duchess is a protector; why would he defend her if there was nothing between them.

Those present burst into loud laughter. “So, in your opinion, Herzegovina is not a country, but a woman,” they exclaimed, “you don’t understand anything, you straight hillbilly!” Since then, a nickname has been established for him for a long time - gray.<…>I ask the reader to keep in mind that I am talking here about the so-called factory workers, who constituted a significant part of the St. Petersburg working population and differed greatly from the factory workers both in their relatively tolerable economic situation and in their habits.<…>The factory worker was a cross between an "intellectual" and a factory worker: a factory worker was something between a peasant and a factory worker. To whom he is closer in his concepts, to a peasant or a factory worker, it depended on how long he had lived in the city.

Russian worker in the revolutionary movement // Revolutionaries of the 1870s: Memoirs of participants in the populist movement in St. Petersburg. Lenizdat, 1986

Philosophical and literary heritage of G.V. Plekhanov in three volumes

TOP SECRET

From a political review for 1892 by the head of the Yekaterinoslav provincial gendarmerie department, D. I. Boginsky, on the causes of workers' unrest in M. Yuzovka. February 9, 1893

The reason for the latest disturbances in the town of Yuzovo, as established now and as witnesses of the disturbances and persons who are quite competent (as proof of which I can present written statements to me from persons who are quite trustworthy), was the exploitation in the broad sense of the word of the workers as mine owners by all without exceptions and in particular the French company and merchants. Indeed, the examples of the exploitation of workers by these individuals surpass any description; suffice it to stipulate that the workers in the majority (mostly without a passport) never fully receive wages (So in the original; follows; earned money (approx. comp.)) , but only a payslip that shows products (for example: tea, sugar and etc.) at a very high price, which they never demanded; and in many mines (mainly in the mines of Alchevsky-“Alekseevsky”, Slavyanoserbsky district), settlement is made in 2-3 months once, and then not in cash, but in “coupons”, which are accepted by local merchants with a deduction of 20% from the cost of the coupon.

The unrest in the town of Yuzovo recurs every year to a greater or lesser extent and, according to the statements of the workers themselves, will undoubtedly be repeated until order and a complete reform in the relations of employers with workers are introduced and, moreover, the admission of unpassported people is stopped. To testify to the indifferent, inhuman attitude of the mine owners towards the workers, it is enough to mention that from August 14 to September 18, there were up to 12 accidents with injury and death for workers due only to ignoring the necessary technical means for the safety of workers.

FORMATION OF THE RUSSIAN-FRENCH UNION

The Franco-Russian alliance became a turning point in Russia's foreign policy. The basis for his conclusion was the presence of common opponents - England and Germany.

Germany's refusal in 1890 to renew the "reinsurance treaty" and its renewal in 1891 of the Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and Italy created fertile ground for Russian-French rapprochement. Russia, fearing to remain in international isolation, was looking for an ally capable of supporting her in the struggle with Germany and Austria-Hungary for spheres of influence in Europe and with Great Britain for spheres of influence in Asia.

On the other hand, the internal political crisis in the mid-1980s, the aggravation of relations with England and Italy on the basis of colonial policy, and tense relations with Germany also placed France in an isolated position in Europe. Thus, in the current international situation, this alliance was beneficial to both states. Rapprochement with France, the old opponent of Germany, and in that situation, England, was prepared by life itself.

In the summer of 1891, a French squadron under the command of Admiral Gervais arrived in Kronstadt. The meeting of the French ships resulted in a demonstration of Russian-French unity.

On August 27, 1891, letters were exchanged in Paris on the coordination of the actions of both powers in the event of a military threat to one of them. A year later, a similar secret military convention was signed between the Russian and French general staffs, and on October 1 (13), 1893, the Russian squadron, consisting of five ships, solemnly embarked on the roadstead of the Toulon port. Thus began a ten-day visit of Russian sailors to France, where they were expected by an enthusiastic reception.

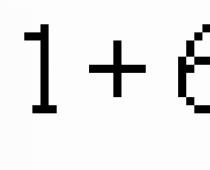

In addition to Toulon, Russian sailors visited Marseille, Lyon and Paris, which were festively decorated to welcome guests. Special souvenirs with symbols of Russian-French unity were sold everywhere. So, the front side of one of the souvenir tokens, which were attached to clothes, was decorated with two daggers with the inscription: “Long live France - Long live Russia”, and the reverse side was decorated with the equation “1 + 1 = 3”. This symbolized that the Russian-French alliance was a reliable counterbalance to the Triple Alliance of Germany, Italy and Austria-Hungary.

Selecting the right candidate for the command of this squadron, Alexander III ordered to give him a list of rear admirals who did not speak French well. It was this circumstance that determined the fact that F.K. was appointed commander of the squadron. Avelan, so that, according to the emperor, "talk less there." The officers of the squadron were ordered to exercise caution and restraint in expressing their political convictions in relations with the French.

The final formalization of the Russian-French alliance took place in January 1894, when the Russian-French treaty was ratified Russian emperor and the French President.

I.E. Repin. Reception of volost foremen by Emperor Alexander III in the courtyard of the Petrovsky Palace in Moscow. 1885-1886

Alexander III Alexandrovich Romanov

Years of life: February 26, 1845, Anichkov Palace, St. Petersburg - October 20, 1894, Livadia Palace, Crimea.

Son of Maria Alexandrovna, recognized daughter of Grand Duke Ludwig II of Hesse and Emperor.

Emperor of All Russia (1 (13) March 1881 - October 20 (November 1), 1894), Tsar of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland from March 1, 1881

From the Romanov dynasty.

He was awarded a special epithet in pre-revolutionary historiography - the Peacemaker.

Biography of Alexander III

He was the 2nd son of the imperial family. Born February 26 (March 10), 1845 in Tsarskoye Selo His elder brother was preparing to inherit the throne.

The mentor who had a strong influence on his worldview was K.P. Pobedonostsev.

As a prince, he became a member of the State Council, commander of the guards and chieftain of all Cossack troops.

During the Russian-Turkish war of 1877–1878. he was the commander of the Separate Ruschuk Detachment in Bulgaria. He created the Volunteer Fleet of Russia (since 1878), which became the core of the country's merchant fleet and the reserve of the Russian military fleet.

After the death of his elder brother Nicholas in 1865, he became the heir to the throne.

In 1866, he married the bride of his deceased brother, the daughter of the Danish king Christian IX, Princess Sophia Frederica Dagmar, who adopted the name Maria Feodorovna in Orthodoxy.

Emperor Alexander 3

Having ascended the throne after the assassination of Alexander II on March 1 (13), 1881  (his father's legs were blown off by a terrorist bomb, and his son spent the last hours of his life nearby), canceled the draft constitutional reform signed by his father just before his death. He stated that Russia would pursue a peaceful policy, would internal problems- strengthening autocracy.

(his father's legs were blown off by a terrorist bomb, and his son spent the last hours of his life nearby), canceled the draft constitutional reform signed by his father just before his death. He stated that Russia would pursue a peaceful policy, would internal problems- strengthening autocracy.

His manifesto of April 29 (May 11), 1881 reflected the program of domestic and foreign policy. The main priorities were: maintaining order and power, strengthening church piety and ensuring the national interests of Russia.

Reforms of Alexander 3

The tsar created the State Peasant Land Bank to issue loans to peasants for the purchase of land, and also issued a number of laws to alleviate the situation of the workers.

Alexander 3 pursued a tough policy of Russification, which faced opposition from some Finns and Poles.

After Bismarck's resignation from the post of Chancellor of Germany in 1893, Alexander III Alexandrovich concluded an alliance with France (Franco-Russian alliance).

In foreign policy, for years of reign of Alexander 3 Russia has firmly taken a leading position in Europe. Possessing a huge physical strength, the tsar symbolized for other states the power and invincibility of Russia. Once the Austrian ambassador began to threaten him during dinner, promising to move a couple of army corps to the borders. The king listened in silence, then took a fork from the table, tied it in a knot and threw it on the ambassador's plate. “This is what we will do with your couple of hulls,” the king replied.

Domestic policy of Alexander 3

Court etiquette and ceremonial became much simpler. He significantly reduced the staff of the Ministry of the Court, the number of servants was reduced and strict control over the spending of money was introduced. At the same time, a lot of money was spent on the acquisition of art objects by him, since the emperor was a passionate collector. Gatchina Castle under him turned into a storehouse of priceless treasures, which later became a true national treasure of Russia.

Unlike all his predecessors-rulers on the Russian throne, he adhered to strict family morality and was an exemplary family man - a loving husband and a good father. He was one of the most pious Russian sovereigns, firmly adhered to the Orthodox canons, willingly donated to monasteries, to build new churches and restore ancient ones.

Passionately fond of hunting and fishing, boating. Belovezhskaya Pushcha was the Emperor's favorite hunting ground. He participated in archaeological excavations, loved to play the trumpet in a brass band.

The family had very warm relations. Every year the date of marriage was celebrated. Evenings for children were often arranged: circus and puppet performances. Everyone was attentive to each other and gave gifts.

The emperor was very hardworking. And yet, despite a healthy lifestyle, he died young, before reaching the age of 50, quite unexpectedly. In October 1888, the tsar's train crashed near Kharkov. There were many victims, but the royal family remained intact. Alexander, with incredible efforts, held the collapsed roof of the car on his shoulders until help arrived.

But soon after this incident, the emperor began to complain of back pain. Doctors came to the conclusion that a terrible concussion during the fall served as the onset of kidney disease. At the insistence of the Berlin doctors, he was sent to the Crimea, to Livadia, but the disease progressed.

On October 20, 1894, the emperor died. He was buried in St. Petersburg, in the Peter and Paul Cathedral.

The death of Emperor Alexander III caused an echo all over the world, flags were lowered in France, memorial services were held in all churches in England. Many foreign figures called him a peacemaker.

The Marquess of Salisbury said: “Alexander III saved Europe many times from the horrors of war. According to his deeds, the sovereigns of Europe should learn how to manage their peoples.

He was married to the daughter of the Danish king Christian IX Dagmar of Denmark (Maria Feodorovna). They had children:

- Nicholas II (May 18, 1868 - July 17, 1918),

- Alexander (May 20, 1869 – April 21, 1870),

- Georgy Alexandrovich (April 27, 1871 - June 28, 1899),

- Xenia Alexandrovna (April 6, 1875 - April 20, 1960, London), also Romanova by her husband,

- Mikhail Alexandrovich (December 5, 1878 - June 13, 1918),

- Olga Alexandrovna (June 13, 1882 - November 24, 1960).

He had a military rank - general of infantry, general of cavalry (Russian Imperial Army). The Emperor was of enormous stature.

In 1883, the so-called "coronation ruble" was issued in honor of the coronation of Alexander III.

Alexander III (1845-1894) was the second son of Emperor Alexander II. He became heir to the throne only at the age of 20, after the sudden death of his elder brother. Began hasty preparation of Alexander Alexandrovich for this role. He received a good education, knew military affairs, was fond of history, knew languages \u200b\u200bwell ...

In the autumn of 1866, he married the Danish princess Dagmar, who was named Maria Feodorovna at her marriage. The emperor was fond of fishing, hunting, was distinguished by his huge growth, dense physique, possessed remarkable physical strength, wore a beard and a simple Russian dress.

The death of his father shocked Alexander Alexandrovich. When he looked at the bloody "tsar-liberator", who was dying in terrible agony, he vowed to strangle the revolutionary movement in Russia. The program of the reign of Alexander III contained two main ideas - the most severe suppression of any opponents of power and the cleansing of the state from "alien" Western influences, the return to the Russian foundations - autocracy, Orthodoxy, nationality.

On March 2, 1881, while receiving members of the State Council and courtiers who took the oath, the new tsar declared that, entering the throne at a difficult moment, he hoped to follow his father's precepts in everything.

On March 4, in dispatches to Russian ambassadors, the emperor emphasized that he wanted to maintain peace with all powers and focus all attention on internal affairs.

Alexander III knew that his father had approved Loris-Melikov's project. Among the government officials who gathered on March 8 for a meeting, the supporters of the project were in the majority. However, the unexpected happened. Alexander III supported the minority of opponents of the project, through whose mouths he broadcast K. P. Pobedonostsev.

Document.

From the speech of K. P. Pobedonostsev. March 8, 1881

What is the Constitution? Western Europe gives us the answer to this. The constitutions that exist there are the instrument of any untruth, the instrument of all intrigues... And this falsehood according to the Western model, unsuitable for us, they want, to our misfortune, to our destruction, to introduce in our country. Russia was strong thanks to the autocracy, thanks to unlimited trust and close ties between the people and their tsar ... But instead of that they propose to set up a talking shop for us ... We already suffer from talking ...

In such a terrible time ... one must think not about the establishment of a new one, in which new corrupting speeches would be made, but about deeds. We need to act.

In June 1881, the first so-called "session of knowledgeable people" was convened, who were invited to take part in development of a law on the reduction of redemption payments. And although "knowledgeable people" were not elected by the zemstvos, but were appointed by the government, among them were prominent liberal figures. The second "session of knowledgeable people", held in September 1881, was proposed the issue of resettlement policy.

- The new posts were by no means opposed to any reforms. The Minister of Internal Affairs N.P. Ignatiev, a prominent Slavophile I.S. Aksakov, he developed a project for convening an advisory Zemsky Cathedral. N. X. Bunge became Minister of Finance.

- December 28, 1881 was adopted after a preliminary discussion at the "session of knowledgeable people" the law on the obligatory redemption of allotments by peasants. Thereby the temporarily obligated state of the peasants was terminated.

- position on the widespread reduction of redemption payments for 1 ruble. Later, 5 million rubles were allocated for their additional reduction in some provinces.

- the abolition of the poll tax.

- Bunge significantly streamlined the collection of taxes, which up to that time had been carried out by the police often with the most unceremonious methods.

- were introduced positions of tax inspectors, which were entrusted not only with the collection of money, but also with the collection of information about the solvency of the population in order to further regulate taxation.

- Measures were taken in 1882 to alleviate the land shortage of the peasants.

- was the Peasants' Bank was established, which provided soft loans for the purchase of land by peasants; secondly, the lease of state lands was facilitated.

- The law on resettlement appeared only in 1889 and actually included measures proposed by "knowledgeable people": only the Ministry of the Interior gave permission for resettlement; migrants were provided with significant benefits - they were exempted for 3 years from taxes and military service, and in the next 3 years they paid taxes in half; they were given small amounts of money.

- the government of Alexander III sought preserve and strengthen the peasant community, believing that it prevents the ruin of the peasants and maintains stability in society.

- In 1893 was adopted law restricting the possibility of peasants leaving the community. A law was passed prohibiting the sale of communal lands.

- August 14, 1881 published "Regulations on Measures for the Protection of State Order and Public Peace". This document gave the right to the Minister of the Interior and the governors-general to declare any region of the country in an "exceptional position." Local authorities could expel unwanted persons without a court decision, close commercial and industrial enterprises, refer court cases to a military court instead of a civil one, suspend the publication of newspapers and magazines, and close educational institutions.

- In the 80s. created Departments for the protection of order and public safety - "guards". Their task was to spy on the opponents of the authorities.

June 1, 1882 was published a law prohibiting the labor of children under 12 years of age. The same document limited the working day of children from 12 to 15 years old to 8 hours.

In 1885 followed prohibition of night work for women and minors.

The law on the relationship between employers and workers was passed. He limited the amount of fines. It was forbidden by law to pay for work goods through factory shops. Special paybooks were introduced, in which the conditions for hiring a worker were entered.

the law provided severe responsibility of workers for taking part in strikes.

Russia became the first country in the world to exercise control over the working conditions of workers.

Emperor Alexander III (1845-1894) ascended the throne after the assassination of his father Alexander II by terrorists. Ruled the Russian Empire in 1881-1894. He showed himself to be an extremely tough autocrat, mercilessly fighting any revolutionary manifestations in the country.

On the day of his father's death, the new ruler of Russia left the Winter Palace and, surrounding himself with heavy guards, took refuge in Gatchina. Ta on long years became his main stake, since the sovereign was afraid of assassination attempts and was especially afraid of being poisoned. He lived extremely closed, and security was on duty around the clock.

The years of the reign of Alexander III (1881-1894)

Domestic politics

It often happens that the son holds different views than the father. This state of affairs was also characteristic of the new emperor. Having ascended the throne, he immediately established himself as a consistent opponent of his father's policy. And by the nature of his character, the sovereign was not a reformer and thinker.

Here one should take into account the fact that Alexander III was the second son, and the eldest son Nicholas was prepared for state activity from an early age. But he fell ill and died in 1865 at the age of 21. After that, Alexander was considered the heir, but he was no longer a boy, and by that time he had received a rather superficial education.

He fell under the influence of his teacher K. P. Pobedonostsev, who was an ardent opponent of Western-style reforms. Therefore, the new king became the enemy of all those institutions that could weaken the autocracy. As soon as the newly-made autocrat ascended the throne, he immediately removed all his father's ministers from their posts.

First of all, he showed the rigidity of character in relation to the murderers of Alexander II. Since they committed the crime on March 1, they were called March 1st. All five were sentenced to death by hanging. Many public figures asked the emperor to replace the death penalty with imprisonment, but the new ruler of the Russian Empire upheld the death sentence.

The police regime has noticeably increased in the state. It was reinforced by the "Regulation on enhanced and emergency protection." As a result, protests have noticeably decreased, and terrorist activity has sharply declined. Only one successful attempt was recorded on the prosecutor Strelnikov in 1882 and one failed on the emperor in 1887. Despite the fact that the conspirators were only going to kill the sovereign, they were hanged. In total, 5 people were executed, and among them was Lenin's older brother Alexander Ulyanov.

At the same time, the situation of the people was relieved. Purchase payments fell, banks began to issue loans to peasants for the purchase of arable land. Poll taxes were abolished, night factory work for women and adolescents was limited. Also, Emperor Alexander III signed a decree "On the conservation of forests." Its execution was entrusted to the governors-general. In 1886, the Russian Empire established a national holiday, the Railwayman's Day. The financial system stabilized, and industry began to develop rapidly.

Foreign policy

The years of the reign of Emperor Alexander III were peaceful, so the sovereign was called peacemaker. He was primarily concerned with finding reliable allies. Relations with Germany did not develop due to trade rivalry, so Russia moved closer to France, which was interested in an anti-German alliance. In 1891, the French squadron arrived in Kronstadt on a friendly visit. The emperor himself met her.

He twice prevented a German attack on France. And the French, in gratitude, named one of the main bridges across the Seine in honor of the Russian emperor. In addition, Russian influence in the Balkans increased. Clear boundaries were established in the south of Central Asia, and Russia was completely entrenched in the Far East.

In general, even the Germans noted that the emperor of the Russian Empire was a real autocrat. And when enemies say this, it is worth a lot.

The Russian emperor was deeply convinced that the royal family should be a role model. Therefore, in personal relationships, he adhered to the principles of worthy Christian behavior. In this, apparently, the fact that the sovereign was in love with his wife played an important role. She was the Danish princess Sophia Frederika Dagmar (1847-1928). After the adoption of Orthodoxy, she became Maria Feodorovna.

At first, the girl was predicted to be the wife of the heir to the throne, Nikolai Alexandrovich. The bride came to Russia and met the Romanov family. Alexander fell in love with a Dane at first sight, but he did not dare to express it in any way, since she was the bride of his older brother. However, Nikolai died before the wedding, and Alexander's hands were untied.

Alexander III with his wife Maria Feodorovna

In the summer of 1866, the new heir to the throne made the girl an offer of marriage. Soon the engagement took place, and on October 28, 1866, the young people played a wedding. Maria fit perfectly into the metropolitan society, and a happy marriage lasted almost 30 years.

Husband and wife parted very rarely. The Empress even accompanied her husband on a bear hunt. When the spouses wrote letters to each other, they were filled with love and care for each other. In this marriage, 6 children were born. Among them is the future Emperor Nicholas II. Maria Feodorovna, after the start of the revolution, went to her homeland in Denmark, where she died in 1928, having outlived her beloved husband for a long time.

idyll family life nearly destroyed by a railroad accident on October 17, 1888. The tragedy occurred near Kharkov near the Borki station. The royal train was carrying a crowned family from the Crimea and was moving at high speed. As a result, he derailed on a railway embankment. At the same time, 21 people died and 68 were injured.

As for the royal family, at the time of the tragedy she was having lunch. The dining car fell off the embankment and collapsed. The roof of the car collapsed down, but the Russian Tsar, who had a powerful physique and a height of 1.9 meters, put his shoulders up and held the roof until the whole family got to a safe place. Such a happy ending was perceived by the people as a sign of God's grace. Everyone began to say that now nothing terrible would happen to the Romanov dynasty.

However, Emperor Alexander III died relatively young. His life was cut short on October 20, 1894 in the Livadia Palace (the royal residence in the Crimea) from chronic nephritis. The disease gave complications to the vessels and heart, and the sovereign died at the age of 49 (read more in the article Death of Alexander III). On the Russian throne Emperor Nicholas II Romanov entered.

Leonid Druzhnikov

- In contact with 0

- Google+ 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0