It took the Romans almost half a century to fully recover from the Gallic pogrom. But, when they managed to do this, Rome was ready to solve the global task of subordinating all of Italy to its power. The First Samnite War (343-341) opened a qualitatively new period in the history of Rome. The Romans themselves were already aware of this. Livy (VII, 29) writes: “From now on, we will talk about more significant wars, as they fought against stronger enemies, in more distant lands and in time much longer. The fact is that it was in this year that swords had to be drawn against the Samnites, a populous and warlike tribe; the Samnite war, which was fought with varying success, was followed by a war with Pyrrhus, Pyrrhus with the Punians. How much did they take! How many times have we stood on the brink of destruction in order to finally erect this sovereign bulk, threatening (now) to collapse! (translated by N. V. Braginskaya).

latin war

Under such circumstances, by 340 the following situation had developed in Central Italy: on the one hand, the Roman-Samnite alliance was restored; on the other hand, an extensive coalition of Latins, Campanians, Avruncas and Volsci was formed. Tradition makes the demand of the Latins for one consular seat and half the seats in the senate a casus belli. It is possible that such a requirement is a modernization introduced by later annalistics, and in reality it was simply a matter of restoring the old independence of the Latin communities. But whatever the nature of the ultimatum, the Roman government rejected it, and a war began, known as the Latin War (340-338).

The tradition about her is replete with many fictitious facts and is largely unreliable.

In particular, in Livy (VIII, 6-10) we find well-known legends about the consuls of 340 - Titus Manlius Torquata and Publius Decius Musa. Since the struggle with the Latins was in the nature of an almost civil war, the consuls strictly forbade any communication with enemies and even separate skirmishes outside the general order. The son of Manlius, a brave and beloved young man, during the reconnaissance, forgetting about the prohibition, entered into single combat with the commander of the Latin detachment and killed him. With triumph he returned to his father, talking about his victory. But the stern consul before the formation condemned him to death as a soldier who violated the order, and, despite the horror and pleas of the entire army, ordered his son to be executed, showing an example of cruel but necessary discipline.

Another legend says that both consuls had the same dream. They introduced themselves to a man of unusual height and appearance, who said that on whose side the leader dooms the enemy army and himself to death, victory will belong to that side. The consuls decided that one of them would doom himself to death, whose army began to retreat. In a battle near Mount Vesuvius, at a decisive moment, the left wing, commanded by Decius, faltered. Then the consul, in solemn words, sacrificing himself and his enemies to the gods, threw himself into the midst of enemies and perished. His death caused such an uplift of spirit among the Romans that they rushed at their opponents with a vengeance and won a brilliant victory.

In a great battle near Tryfan near Suessa, the Romans defeated the Latins and their allies, after which they concluded a separate peace with the Campanians, bribing the Capuan aristocracy with the rights of Roman citizenship. The Latins and Volsci then resisted for another two years, but finally also surrendered.

The results of the war were very significant for both sides. Rome first of all tried to insure itself against joint actions of the Latin allies in the future. Therefore, all coalitions between the Latin communities were forbidden, and those of them who did not receive Roman citizenship were deprived of the right to enter into business relations with each other (ius commercii) and marry (ius conubii). In relation to the Latins as a whole, the Roman Senate adopted a very reasonable policy, which later began to be pursued in relation to other Italics. This policy, as stated above, was to put the conquered communities in a different legal position in relation to Rome. This achieved their isolation from each other and their varying degrees of interest in Roman affairs. Thus, for example, the Latin colonies (Ardea, Circe, Sutrius, Nepete, and others) were left in the old position of the allies. The largest restless Latin cities, such as Tibur and Praeneste, lost part of their territory, and Rome concluded separate allied treaties with them. A number of the most faithful communities (Tusculus, Lanuvius, Aricia, etc.) were simply annexed to Rome and received full citizenship, and two new tribes were formed in Latium.

The Latin War dealt the final blow to the Volsci. Antium completely capitulated and was turned into a colony of Roman citizens. His fleet passed into the hands of the Romans. The large ships were burned, and only their prows were exhibited as trophies in the Roman forum, where they adorned the oratory (rostra). This fact is very remarkable, as it shows the low level of maritime development in Rome in this era. Satricus and Tarracina were also turned into Roman colonies. The remnants of the Volscians were driven into the mountains.

The communities of the Avrunks were placed in a special legal position known as communities without the right to vote (civitates sine suffragio). This meant that their inhabitants performed all the duties of Roman citizens (for example, they performed military service) and enjoyed civil rights, but only without political rights: without the right to vote in comitia and elect to public office.

As for Campania, here the main task of Rome was to bind to itself as closely as possible this flourishing region, to which the Romans owed much in their economic and cultural development. On the other hand, the Campanians had to gain a lot from the fact that in Rome they found a protector from their restless neighbors. The Campanian cities (Capua, Cum, Suessula, etc.) received rights that partly resembled the position of the allies, partly - communities without the right to vote. So, for example, the Campanians were considered Roman citizens and served in the legions. But their legions were formed separately from the actual Roman ones. In addition, the Campanians, in particular Capua, retained extensive local self-government. The Campanians did not have the right to participate in Roman popular assemblies and to be elected to Roman public office. To this it must be added that these limited rights were given only to the Campanian aristocracy (the so-called horsemen), who remained loyal to Rome during the war of 340-338. The rest of the population was made dependent on the horsemen and had to pay them an annual tax.

Thus, by the 30s. 4th century Rome became the largest state in Italy, under whose authority was actually Southern Etruria, the whole of Latium, the region of Avrunci and Campania. A decisive struggle against the Samnites became inevitable.

The Latin War immortalized the name of the Roman consul Publius Decius Musa and marked the beginning of the famous Decius Musian family tradition of sacrificing their lives on the battlefield for the victory and glory of Rome. Apparently, it makes sense to tell more about this family tradition.

After 45 years, Publius Decius son repeated the feat of his father. It happened at the battle of Sentin, where the Romans were opposed by a coalition of Gauls, Etruscans and Samnites. The story of Livy (X, 28) is again very colorful: “... Decius, at his age and with his courage, inclined to more decisive actions, immediately threw into battle all the forces at his disposal. And when the foot battle seemed too sluggish to him, he throws his cavalry into battle and, joining the most desperate detachments of youngsters, calls on the flower of youth to hit the enemy with him: double, they say, glory awaits them if victory comes from the left wing, and thanks to the cavalry. Twice they repulsed the onslaught of the Gallic cavalry, but when the second time they got too far away from their own and fought already in the thick of the enemies, they were frightened by an unprecedented attack: armed enemies, standing on chariots and carts, moved towards them under the deafening clatter of hooves and the roar of wheels and frightened the Roman horses, unaccustomed to such noise. As if mad, the victorious Roman cavalry dispersed: headlong rushing away, both horses and people fell to the ground ...

Decius began to shout to his people: where, they say, run, what promises you flight? He blocked the way for those who retreated and called out those who were scattered. Finally, seeing that there was nothing to restrain the confused, Publius Decius, calling by name to his father, exclaimed as follows: “Why should I put off the performance of family fate any longer! to sacrifice himself to the Earth and the gods of the underworld along with the enemy armies! With these words, he orders the pontiff Mark Livius (who, going out to battle, ordered to be inseparable with him) to pronounce the words so that, repeating them, he would doom himself and the enemy legions to the army of the Roman people of the Quirites. And dooming himself with the same spells and in the same attire as his parent, Publius Decius, ordered to doom himself on the Weser in the Latin war, he added to the curses that he would drive ahead of him horror and flight, blood and death, the wrath of heaven gods and the underworld and turn sinister curses on the banners, weapons and armor of enemies, and the place of his death will be the place of extermination of the Gauls and Samnites. With these curses both to himself and to his enemies, he let his horse go where he noticed that the Gauls were the densest, and, throwing himself on the exposed spears, met his death ”(translated by N. V. Braginskaya). Also, the grandson of the consul of 340, Publius Decius Mus, did not violate the family tradition and repeated the feat of his father and grandfather in the battle of Ausculum in 279 (Dionysius. Ancient Roman History, XX, 1-3).

Second Samnite War

A number of military clashes, dragging on for almost 40 years (328-290) and known as the Second and Third Samnite Wars, are much broader in content than the name. The struggle was not only with the Samnites, but also with other tribes of Central and Northern Italy: the Etruscans, Gauls, Guernics, Equami, and so on. In some periods (for example, at the beginning of the 3rd century), the war with the Samnites generally receded into the background compared to the struggle in the north. Therefore, the name Samnite Wars is a rather conditional and collective term. By this term, we designate the decisive stage in the struggle for Roman hegemony in Italy, when all its former and present opponents united against Rome in a desperate and historically already doomed attempt to defend their independence. True, this stage was not the last (Southern Italy still remained), but the most important, since its outcome determined the fate of all of Italy.

The Second Samnite War (328-304) began mainly over Naples. This was no accident, since Rome, having captured Campania, came into close contact not only with the Samnites of the Lyris valley, but also with the hill tribes of Samnium itself. For the latter, the capture of Campania by the Romans meant not only the loss of a seductive plunder and an important market for mercenaries, but also the loss of access to the sea. Apparently, in Naples, which preserved the Greek culture, the struggle between the aristocratic and democratic parties intensified. The latter turned to the Samnite city of Nola and brought a detachment of Samnite mercenaries into Naples. The Neapolitan aristocrats, in turn, called on the help of the Capuans, and through them the Romans (327).

The Roman Senate in its Italian policy is generally characterized by the constant support of aristocratic elements. Here the situation was especially seductive, since the outcome of the case promised the capture of such an important center as Naples was. Therefore, a Roman army under the command of the consul of 327, Quintus Publilius Philo (the former dictator of 339, famous for his reform), laid siege to Naples, while the army of another consul covered the besieging troops. The siege dragged on into the next 326. Then Publius was extended his military powers for another year with the rank of proconsul (“instead of consul”). This was the first time in the Roman practice of extending the military empire; in the future, similar cases will become quite frequent.

In the context of the blockade, the situation in Naples changed. The pro-Roman aristocratic party took over, which fraudulently removed the Samnite garrison and surrendered the city to the Romans. An alliance was concluded with Naples.

This incident served as a pretext for war with the tribes of Central Samnium. As for the Western Samnites, the struggle with them began as early as 328 because the Romans founded a colony in the city of Fregella on the middle reaches of the Liris. The first years of the war were fought without decisive success on either side, but in 321 the Romans suffered a catastrophe in Central Samnium. The struggle here proved to be very difficult for Rome. The Roman army was still poorly adapted to war in mountainous terrain. The brave Samnites, distinguished by a passionate love for their mountains, acted in small partisan detachments, with which the Romans at first did not know how to fight. In addition, the Samnites had a talented leader - Gavius Pontius, who managed to lure the Romans into a trap. Both consuls of 321, deceived by false information that the main forces of the Samnites were in Apulia, moved from Campania into the depths of Samnium. Not far from the city of Caudia, in the southwestern part of Samnium, the Roman army was ambushed in a narrow wooded gorge. The situation turned out to be hopeless, since it was impossible to break through by force, and food supplies were depleted. The consuls lost heart and made a shameful peace in their own name. The Romans had to leave the area of the Samnites, withdraw their colonies from there and give an obligation not to resume wars. To ensure these conditions, they issued 600 hostages from the aristocratic part of the army. But the Samnites could not deny themselves the pleasure of bringing the humiliation of a hated enemy to the most extreme degree. The Roman army was forced to surrender all their weapons, and half-dressed warriors passed one by one under the yoke, showered with a hail of ridicule and mockery from the Samnites standing around. The Roman Senate had no choice but to recognize the shameful peace, which lasted about 6 years.

The vanity of the Roman annalists, of course, could not be satisfied here with a simple statement of a sad fact. A romantic story was invented, how the consuls, the perpetrators of the shameful surrender, persuaded the senate not to recognize the peace of Kavdin and hand them over to the Samnites bound. But Gavius Pontius allegedly refused to accept the extradited consuls. The weapons and hostages were returned to the Romans. The war immediately resumed, and the Romans inflicted several defeats on the Samnites. All this is pure fiction.

Hostilities resumed only at the end of 316. During this six-year period, the Romans, formally without violating the peace, began to penetrate into Apulia, behind the Samnites, and also formed two new tribes in the Avrunci region and in Northern Campania. In 315 one consular army was operating in Apulia, while a second under Publius Philo laid siege to the city of Satikula in the southwestern part of Samnium. The Samnites took advantage of the division of the Roman forces, broke into the Lyris valley and moved on to Latium. The Romans gathered reserves under the command of the dictator Quintus Fabius Rullianus, one of the most prominent generals of this era. Roman and Samnite troops met near the city of Tarracina, in the passage between the Volscian mountains and the sea. The Romans were severely defeated and fled. The head of the cavalry tried to cover the retreat, but was killed. The Samnites took over the Avrunki region and Campania, even Capua was ready to go over to their side. The position of Rome became extremely critical.

However, the Samnites did not manage to fully exploit their successes, and in

314 came a turning point. The Roman troops won a brilliant victory: more than 10 thousand Samnites remained on the battlefield. It changed the whole situation. The leaders of the democratic party in Capua, plotting to fall away from Rome, were handed over to the Romans and executed. Avrunks who behaved in

315 was extremely suspicious, almost completely exterminated, and a Latin colony was brought to Suessa. Many cities that fell away from Rome or were captured by the Samnites (Satric, Fregella, Sora, etc.) were reunited with it. Several new colonies were founded to strengthen Roman influence. Among them, a colony on the small island of Pontus, not far from the southern coast of Latium (313), should be noted. It was the first naval base of the Romans outside of Italy, the foundation of which indicates that maritime affairs in Rome after 338 made some progress. In this regard, there is also the appearance in 311 of two officials to oversee the construction and repair of ships (duoviri navales). It is possible that the deportation of the colony to Ostia, at the mouth of the Tiber, belongs to the same period. Finally, the Appian Way, the construction of which began in 312, was supposed to closely connect Rome with Campania and facilitate further progress into southern Italy.

But the successful conclusion of the Samnite War was overshadowed by a new danger from the Etruscans. In 311, the 40-year truce with them expired. Counting on the fact that the Roman forces were tied up in the south, the troops of Tarquinius and other policies of Northern Etruria laid siege to Sutria. But the consul of 310, Quintus Fabius Rullian, unexpectedly appeared in Northern Etruria by a detour through Umbria and devastated the country, which forced the Etruscans to lift the siege from Sutria. The next year the Romans repeated their raid. These events brought the pro-Roman party to power in the Etruscan cities. Etruscan ambassadors arrived in Rome with a request for peace and alliance. But only a truce was concluded with them for 30 years.

Etruscan affairs brought the Romans into closer contact with the Umbrians, resulting in an alliance with two Umbrian cities. On the other hand, the Roman positions in the fight against the Samnites weakened for some time, and the Romans were forced to go on the defensive. In 308, Samnite troops invaded the region of the Marsi, in close proximity to Latium. The experienced Quintus Fabius was sent to fight them. Another consul was active in northern Apulia. The situation was complicated by the uprising of the old allies of Rome - the Guernics, and then the Equs, incited by the Samnites. Central Italy became the scene of fierce fighting.

By 304, the Romans had achieved decisive successes here. The Samnites sued for peace. The borders of Samnium proper were left almost unchanged, and the region of Lyris was annexed to Latium, and the Samnites quickly disappeared there. Guernica lost its entire territory, except for three cities that retained their former allied relations. The Ekvi were almost completely destroyed, and their entire country, up to Lake Futsin, was annexed to Latium. A number of new colonies appeared in the occupied areas, and two tribes were formed. Allied relations were established with the small tribes of Central Italy, related to the Samnites - the Marsi, Peligni, Frentani, and others.

Third Samnite War

However, the peace was short-lived, and after a six-year break, hostilities resumed. As already mentioned, in the Third Samnite War, the center of gravity lay not so much in the south as in the north, in Etruria. Its traditional chronological framework (298-290) is also conditional. Actually, the beginning new series military clashes must be considered 299, when the Gallic detachment, reinforced by the Etruscans, appeared on Roman territory and, having devastated it, left with rich booty. This movement was a reflection of the new movements of the Gauls in northern Italy, caused by the appearance of their fellow tribesmen from behind the Alps. By this time, relations with the Samnites also escalated. The latter, hoping perhaps that the attention of the Romans was diverted to the north, tried to increase their influence in Lucania. The Senate considered this sufficient reason for declaring war (298). The consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, whose elogy was mentioned above, invaded southwestern part Samnius, took two insignificant points there and received hostages from the Lucans, thereby guaranteeing their loyalty to Rome.

More significant were the successes of the Romans in Northern Samnium. The second consul in 298 defeated the Samnite troops and took the city of Bovian, the center of the Samnite tribal union. These successes were continued by the consuls of 297, Quintus Fabius Rullianus and Publius Decius Mus, son of the famous consul of 340. The Samnites were on the eve of complete defeat, but the hour of their death had not yet come. Moreover, the balance of power suddenly changed so dramatically that not over Samnium, but over Rome, a terrible danger hung.

In 295, the Gauls again moved south and joined with the Etruscans. Samnite detachments also broke through to help them. Thus, for the first time, Rome had before her the combined forces of her main opponents. Both famous commanders, Fabius and Decius, were sent against the enemy. The first clash in Central Umbria was unsuccessful for the Romans: their vanguard was defeated. But a few days later, the main forces of the Romans utterly defeated the allies in a fierce battle at Sentin in Northern Umbria (295). According to Greek historians, 100 thousand Gauls and their allies fell in the battle, including the outstanding Samnite commander Gellius Egnatius.

Livy (X, 28) conveys the story of the heroic death of Publius Decius, exactly duplicating the legend of the death of his father in the battle of Vesuvius in 340. There is a similar story about the death of the third Publius Decius Musa, who doomed himself to the underground gods in the battle with King Pyrrhus at Ausculum (279). If the legend is not pure fiction, then two stories seem to copy the original, which is most likely the latest one.

The battle of Sentin, in essence, decided the outcome of the war, that is, the fate of Italy. The alliance of opponents of Rome broke up. The remnants of the Gauls and Samnites retreated in different directions: some to the north, others to the south, and the Etruscan cities that took part in the anti-Roman movement were forced to agree to a 40-year truce with the payment of a large indemnity. In Samnia, the struggle continued for several more years. The Romans systematically waged a concentrated offensive, securing it with the foundation of colonies. Separate failures did not weaken the obvious general success of Roman weapons. In 293, the Samnites suffered a major defeat, from which they could no longer recover. Three years later, Manius Curius Dentatus, consul of 290, one of the greatest democratic figures in Rome, completed the rout of the courageous people who had fought for their freedom for so long. The Samnites, as Roman allies, were left with only a small territory centered in the city of Bovian.

The end of the Samnite War freed the hands of the Romans for new actions in the north. They needed to secure their borders there as much as possible against possible attacks by the Gauls. In 290, Curius Dentatus passed through the entire country of the Sabines and conquered it. The reason for the war was the sympathetic mood of the Sabines towards the Samnites, or, perhaps, even active assistance on their part. The surviving part of the tribe received the rights of citizens without the right to vote. A similar fate befell the Piceni in the same year. In the southern part of their region, not far from the sea coast, the Latin colony of Adria was founded, the first fortified point on the Adriatic Sea.

These measures turned out to be quite timely, since already in 285 the Gallic tribe of the Senons, who lived north of Picenum, began to move. The Gauls invaded Northern Etruria and besieged the city of Arretius, which held the side of Rome, while other Etruscan communities supported the Senons. The Roman army sent to help Arretius was repulsed with huge losses. The commander himself fell in battle (284). Curius Dentatus, who replaced the deceased, sent an embassy to the Senones to negotiate the fate of the prisoners. The ambassadors were treacherously killed. Then the Roman troops invaded the region of the Senones (ager Gallicus), defeated them and partly destroyed them, and partly expelled them from the country. On the former territory of the Senones, on the seashore, a colony of Roman citizens, Sena Gallicus, was soon founded.

The fate of the Senones caused the movement of their neighbors, the Boii, who lived beyond the Apennines to the north of Etruria. With large forces, they moved south, joined with the Etruscans and went straight to Rome. The Romans, led by the consul of 283, Cornelius Dolabella, met them near Lake Vadymon, west of the middle reaches of the Tiber, and utterly defeated them. However, the following year, the Gauls repeated their attempt, calling under the banners of all the youth who had barely reached maturity. Having suffered a second defeat, they turned to the Roman government with a request for peace. The Romans, not yet interested in Northern Italy, willingly agreed to conclude a peace treaty.

As for Etruria, the events of the late 80s. decided her fate. The Etruscan cities were forced to conclude separate allied treaties with Rome. Only two policies, Volsinii and Vulci, resisted for another two years, after which they also had to surrender.

Thus, the Second Samnite War with its continuation in the 80s. ended with Rome actually becoming the master of all Italy south of the Po plain and approximately to the northern part of Lucania. The final stage of the conquest of Italy has come.

Conquest of Southern Italy. War with Pyrrhus

At the beginning of the III century. in southern Italy, a difficult situation arose. Greek cities experienced a difficult time in their history. The era of their prosperity is far behind. As early as the beginning of the 4th c. many of them were weakened by the struggle with the Syracusan tyrant Dionysius I. This greatly worsened the position of the Greeks in the face of the tribes of Southern Italy advancing on them: the Lucans, the Bruttians, the Messapians, and others. A long struggle ensued, as a result of which a number of Greek cities passed into the hands of the barbarians. On the west coast, only Velia (Elea) and Rhegium retained their independence. On the east coast, the situation was somewhat better. There, the rich trading city of Tarentum played the role of the foremost fighter against the barbarians. But even he could somehow cope with the onslaught of the Lucans and Messapians, only by inviting the leaders of mercenary detachments from Greece to his service.

Among such mercenaries, the first was the Spartan king Archidamus, who fell in 338 in a battle with the Messapians. Then the Tarentines invited the king of Epirus Alexander, uncle of Alexander the Great. At first he achieved great success against the Lucans and Bruttii and liberated a number of cities. It is possible that he even made an alliance with Rome. But in the end, Alexander quarreled with the Tarentines, lost their support and was killed by the Lucans (330). Then came the Spartan Cleonymus (303). At first, he also achieved great success and forced the Lucans to accept the world. But then the usual quarrels with the Greeks followed, and Cleonymus left Italy. Around 300, the famous Syracusan tyrant Agathocles arrived to help the Tarentines. He took possession of a large part of southern Italy, seeking to create a large monarchy. But in 289 he died, and his kingdom fell apart. The Greeks were left defenseless against new attacks by the natives.

At the end of the 80s. The Lucans attacked the Greek city of Thurii. Considering the futility of all previous attempts to seek help from foreign mercenaries and not wanting to turn to their rival Tarentum, the Furies resorted to the intercession of Rome, with whom they had established friendly relations for three years before. The consul of 282, Gaius Fabricius Luscin, came to the rescue: he defeated the Lucans, who were besieging Thurii, and occupied the city with a Roman garrison. But neither the Furians nor the Tarentines liked this, so when 10 Roman ships appeared in the Tarentine harbor on their way to the Adriatic Sea, the population attacked them and captured five ships. Their crew was partly killed, partly sold into slavery, and the Roman commander of the fleet died during the fight. After this, the Tarentines marched on Thurii and, with the help of a party friendly to them, forced the Roman garrison to clear the city.

The Senate sent an embassy to Tarentum demanding satisfaction, but the ambassadors were insulted by the crowd and returned without achieving anything. Then Rome declared war on Tarentum (281). The consul Aemilius Barbula moved from South Samnium and invaded the Tarentine region. Tarentum had rather large forces, which were joined as allies by the Lucans and the Messapians. But it was not difficult for the tried and tested Roman troops to defeat their opponents. The region of Tarentum was devastated.

At this time, negotiations were already taking place between the Tarentine government and Pyrrhus, king of Epirus, about rendering assistance to Tarentum. The defeat hastened these negotiations. The party friendly to Rome was forced to withdraw from business, and an agreement was concluded with Pyrrhus. In the early spring of 280, Pyrrhus landed in Italy. With him was a relatively small but first-class army, consisting of 20,000 heavy infantry (phalangites), 2,000 archers and 3,000 Thessalian horsemen. In addition, with his army there were 20 war elephants, which first appeared then in Italy. Tarentum promised to put at the disposal of Pyrrhus 350,000 infantry and 20,000 cavalry. Of course, this promise was only partially fulfilled.

In the person of Pyrrhus, the Romans faced one of the most prominent generals of the Hellenistic era, who came out of the school of Alexander the Great, with whom he was distantly related. Pyrrhus was then about 40 years old. From 295 he was king of Epirus, having previously had a very turbulent political career, during which, by the way, he ended up for a short time even on the Macedonian throne, from which he was expelled by Lysimachus. Pyrrhus was an extremely talented commander, not only a practitioner, but also a theoretician: he wrote writings on military affairs, and the great Hannibal himself later called himself his student. However, the character of Pyrrhus was not stable. He constantly rushed about with grandiose plans, dreamed of becoming a second Alexander, easily caught fire, developed huge activities for a while, but quickly cooled down and did not bring a single thing to an end.

Tarentum's invitation came in handy. A few years earlier, Pyrrhus had lost Macedon and was now obsessed with a new plan: to conquer

But at that time, in any case, the defeat of the Romans at Heraclea greatly changed the whole situation in the south. Croton expressed his obedience to Pyrrhus, Locri gave him the Roman garrison. In the Rhegium, where the Roman corps consisted of Campanians, the same might be feared. Then the Campanians took possession of the city, killed the rich and influential citizens and declared themselves independent. Thus, Rhegium did not fall into the hands of Pyrrhus, but was lost to Rome.

The king of Epirus decided to make the most of his victory and marched on Rome. Encountering no resistance anywhere, he approached the city for several tens of kilometers. However, in his rear, Levin put in order and replenished the troops defeated at Heraclea, Capua and Naples remained faithful to Rome, the Roman army, which operated against Volsinia and Vulci, quickly completed its operations and hurried to the aid of Rome, emergency measures were taken in the city for defense. Under such conditions, an attack on Rome became very risky, and Pyrrhus turned back ...

Now he changed tactics and decided to try to start peace negotiations with Rome. He sent his ambassador to Rome, the Thessalian Cineas, who was distinguished by his extraordinary oratory and diplomatic skill. Pyrrhus said that with the help of Cineas he acquired more cities than with his own spear. Rich gifts were sent with Cineas to influential members of the senate. Pyrrhus' proposals were that the Romans should make peace with Tarentum, guarantee autonomy to the Greek cities, and return what they had taken from the Samnites, Lucans, and Bruttians. This, apparently, was about the large colonies of Luceria and Venusia in Northern Apulia and Southern Samnia. Under these conditions, Pyrrhus was ready to end the war and return the prisoners.

Although the gifts of Pyrrhus were rejected, his proposals were seriously discussed in the Senate, where a strong group of supporters of peace was formed, albeit on terms more favorable to Rome. In the midst of the debate, the blind Appius Claudius, then already a very old man, was brought to the senate and delivered a fiery speech. He urged the Senate not to negotiate with the enemy while he was on Italian soil. This speech dramatically changed the mood of the senators, and the negotiations were interrupted.

However, Roman ambassadors, led by Fabricius, were nevertheless sent to Pyrrhus with an offer to ransom the prisoners. The proud and courageous behavior of the senate greatly impressed the king of Epirus, in whose character there was a lot of noble romance. He told the ambassadors: “I did not come here to trade. Let's settle our dispute on the battlefield. As for your prisoners, take them as my gift." According to other reports, Pyrrhus released the prisoners on parole only for the celebration of Saturnalia.

In April 279 hostilities resumed. The Roman troops were commanded by both consuls, one of whom was Publius Decius Mus, the son of the consul who died under Sentinum. The battle took place near Auscula, in Apulia, in a rugged and wooded area, where Pyrrhus could not make full use of his phalanx, cavalry and elephants. Therefore, the first day did not give decisive results. The battle resumed the next day. Pyrrhus managed to take the best positions, and the Romans were defeated, but far from complete, as they held their fortified camp. They lost 6 thousand people and among their consul Decius. The losses of Pyrrhus reached 3.5 thousand, he himself was slightly wounded. Under these conditions, he could not use the victory and retreated to Tarentum.

The difficulties of the war greatly cooled Pyrrhus. In addition, he received news from the Balkan Peninsula, which urgently demanded his return. On the other hand, some Sicilian cities turned to him with a request for help against the Carthaginians, who, after the death of the tyrant Agathocles (289), launched a decisive offensive in Sicily. This request just answered the broad plans of Pyrrhus.

In this situation, more favorable conditions were created for new peace talks. In the winter of 279/78, Fabricius again visited Pyrrhus and worked out with him the preliminary conditions for peace, which this time, apparently, amounted only to the recognition of the independence of Tarentum. Cineas again went to Rome.

But just at that moment, a strong Carthaginian fleet of 120 ships under the command of Mago arrived in Ostia. The Carthaginian government invited Rome to conclude a treaty against Pyrrhus. The secret goal of Carthage was at all costs to prevent the peace being prepared between Rome and the king of Epirus and to detain the latter as long as possible in Italy. On the other hand, the Carthaginian conditions were also beneficial to Rome. We do not know the details of the agreement. The meaning of that part of it, which is given in Polybius (III, 25), and is not quite clearly formulated, boils down to the following. If Pyrrhus enters the territory of one of the contracting parties, then the other side is obliged to deliver reinforcements to the territory of the attacked ally, and must maintain troops at its own expense. In particular, Carthage must deliver transport ships and assist the Romans with its war fleet, but the crew of this fleet is not required to fight for the Romans on land. The advantage for Rome of this part of the treaty was that it made it possible, with the help of the Carthaginian fleet, to attack Tarentum and cut off Pyrrhus in Italy or Sicily. The treaty with Carthage was signed, and Cineas left Rome again without success.

In 278, a new campaign began, taking place on the territory of Tarentum. At the head of the Roman troops were both consuls of this year, one of whom was again Fabricius. The campaign proceeded rather sluggishly, as Pyrrhus was busy preparing the Sicilian expedition, and the Romans did not yet feel strong enough to lay siege to Tarentum.

From the history of this campaign, tradition has preserved a story that adds another touch to the characterization of the mores of that time. The doctor Pyrrhus appeared to Fabricius with a proposal to poison the king for a large sum of money. The consul angrily rejected the proposal and sent the traitor bound to Pyrrhus. The noble king not only returned without ransom all the Roman prisoners, but was ready to agree to peace on extremely favorable terms for the Romans.

It is possible that Cineas once again traveled to Rome with peace proposals, but the senate repeated its previous answer. It made no sense for Rome to conclude peace under the circumstances.

In the autumn of 278, Pyrrhus sailed to Sicily with 10,000 troops, leaving strong garrisons in Tarentum and other Greek cities. In Sicily, after the death of Agathocles, the greatest anarchy reigned, which the Carthaginians took advantage of. Syracuse was blockaded by the Carthaginian fleet. At the first moment, Pyrrhus was received in Sicily with enthusiasm: he was proclaimed king and hegemon of Sicily. All Greeks united to fight a common enemy. Pyrrhus quickly managed to achieve major successes: he forced the Carthaginians to lift the blockade of Syracuse and captured almost all the points they occupied. Only Lilybaeum, a major port in western Sicily, remained in their hands. It could only be taken from the sea.

The Carthaginians offered Pyrrhus a peace treaty on the condition that they purify all of Sicily, except for Lilybaeus. The king, largely under pressure from the Greeks, refused. After unsuccessful attempts to capture Lilybaeum from land, he decided to build a strong fleet in order to deliver a decisive blow to Carthage in Africa.

These grand plans did not meet with the sympathy of the Greeks, for whom they foreshadowed huge expenses, since Pyrrhus, of course, did not intend to build a fleet with his own money. This was joined by dissatisfaction with the autocratic manners of Pyrrhus, his dismissive attitude towards the democratic system of Greek cities, the clear preference that he gave to his officers, and so on. The Greeks realized that Pyrrhus was pursuing his own personal goals, for which they served only as a tool. All this dramatically changed their mood. Things got to the point that some policies turned to their recent enemies, the Carthaginians, for help against Pyrrhus. In the end, only Syracuse remained in his hands.

Pyrrhus faced the difficult task of reconquering the island. He didn't have the patience for that. He took advantage of the first favorable pretext - the Italians again began to ask him for help - and in the spring of 275 he left Sicily. In the strait, the Carthaginian fleet attacked him and destroyed more than half of the ships. Nevertheless, Pyrrhus managed to land in Italy.

During the absence of Pyrrhus, the Romans achieved major successes in the south, in particular, they occupied Croton and Locri and again brought the tribes of Lucans and Samnites who had gone over to the side of Pyrrhus to submission. But the appearance of Pyrrhus forced them to retreat. Leaning still on Tarentum as his main base, the king moved north, gathering all his available forces. Under Benevente in Samnium, his last battle in Italy (275) took place. The Romans were commanded by the consul Manius Curius Dentatus, hero of the Third Samnite War. The second consul went to his aid from Lucania, but did not have time to arrive in time. Pyrrhus, anxious to take a better position before the Romans, undertook a night march, but strayed in the darkness, and thus enabled Manius Curius to deploy his forces. The elephants this time played a fatal role for Pyrrhus: frightened by the Roman arrows covering the camp, they rushed at their own troops and confused them. The Romans captured the camp of Pyrrhus, more than 1 thousand prisoners and four elephants, the appearance of which in Rome, which had never seen them, made an extraordinary sensation.

Pyrrhus, aware of the approach of the second consul, retreated to Tarentum. Having neither money nor troops, having been refused material assistance by the Hellenistic monarchs who subsidized his Italian expedition, Pyrrhus lost all desire to stay longer in Italy. In the autumn of 275, with the remnants of his troops, he left the inhospitable peninsula and crossed over to Greece, leaving a garrison in Tarentum and comforting his frightened allies with a promise to return soon. However, no one believed him anymore... Three years later, Pyrrhus ingloriously ended his days in a street fight in Argos (272).

The victory of the unknown barbarian people over the illustrious commander drew the attention of the entire cultural world of that time to Rome. An expression of this attention was, for example, the embassy sent to Rome in 273 by the most powerful monarch of the Hellenistic East, Ptolemy Philadelphus. Pyrrhus lost the campaign in Italy not only because of his personal qualities, which excluded the possibility for him to pursue a calm and restrained policy, but also because of the heterogeneity of the forces on which he relied. Motley mercenary troops, the Greek cities of Italy and Sicily torn apart by contradictions, the semi-barbarian tribes of Southern Italy - this base was very far from monolithic. And against himself, Pyrrhus had a young, but already strong state, by the beginning of the 3rd century. liquidating all the most acute internal contradictions and uniting a significant part of Italy. During more than two centuries of wars, a Roman military organization was formed that surpassed the Macedonian one, a Roman military school was formed, and persistent and experienced military personnel grew up. Rome imperceptibly for contemporaries has become a major power.

At the beginning of the III century. For the first time, the interests of the Roman Republic and the Hellenistic world clashed. And already from the first clash, Rome emerged victorious. But the Romans were opposed by far from the weakest enemy, moreover, one of the most talented commanders of the ancient world - the Epirus king Pyrrhus. Plutarch chose Pyrrhus as the hero of one of his biographies. Describing the king, Plutarch notes: “Pyrrhus’s face was regal, but the expression on his face was more frightening than majestic. His teeth did not separate from each other: the entire upper jaw consisted of one solid bone, and the gaps between the teeth were marked only by thin grooves. It was believed that Pyrrhus could bring relief to those suffering from spleen disease, if he only sacrificed a white rooster and with his right paw lightly pressed several times on the stomach of the patient lying on his back. And not a single person, even the poorest and humblest, met him with a refusal if he asked for such treatment: Pyrrhus took a rooster and sacrificed it, and such a request was the most pleasant gift for him. They also say that the big toe of one of his feet possessed supernatural properties, so that when, after his death, the whole body burned on a funeral pyre, this toe was found safe and sound” (Pyrrhus, 3). And further Plutarch writes: “A lot was said about him and it was believed that with his appearance and speed of movements he resembles Alexander, and seeing his strength and onslaught in battle, everyone thought that before them was the shadow of Alexander or his likeness, and if the other kings proved his resemblance to Alexander only in purple robes, a retinue, a tilt of his head and an arrogant tone, then Pyrrhus proved it with a weapon in his hands. His knowledge and abilities in military affairs can be judged from the writings on this subject that he left. When asked who he considers the best commander, Antigonus is said to have replied (speaking only of his contemporaries): "Pyrrhus, if he lives to old age." And Hannibal claimed that Pyrrhus was superior in experience and talent to all generals in general, he assigned the second place to Scipio, and the third to himself ... Pyrrhus was favorable to those close to him, not angry and always ready to immediately do good deeds to his friends ... Once a young man was caught who scolded him during a drinking bout, and Pyrrhus asked if it was true that they had such conversations. One of them replied: "It's true, king. We would talk even more if we had more wine." Pyrrhus laughed and let everyone go” (Pyrrhus, 8, translated by S. A. Osherov). Tarentum's invitation came at the right time for Pyrrhus: at last he could begin to realize his long-standing dream - to create his own power in the West, similar to Alexandrov in the East. At first, success accompanied him: the Romans were defeated at Heraclea, and the senate was ready to conclude a peace favorable to Pyrrhus. Only at the last moment did the senators change their minds, ashamed and inspired by the fiery speech of Appius Claudius Caecus. Plutarch described this episode in detail in the biography of Pyrrhus: “In the meantime, Appius Claudius found out about the royal embassy. An illustrious man, he, out of old age and blindness, left state activity, but when rumors spread that the senate was going to decide on a truce, he could not stand it and ordered the slaves to carry him on a stretcher through the forum to the curia. His sons and sons-in-law surrounded him at the door and led him into the hall; the senate met him with respectful silence. And he, immediately taking the floor, said: “Until now, Romans, I could not come to terms with the loss of sight, but now, hearing your meetings and decisions that turn the glory of the Romans into nothing, I regret that I am only blind, and where are the words that you repeat and repeat to everyone and everywhere, the words that if the great Alexander came to Italy and met us when we were young, or with our fathers, who were then in their prime strength, then they would not now glorify his invincibility, but by his flight or death he would raise the glory of the Romans? You proved that all this was chatter, empty boasting! You are afraid of the Molossians and Chaons, who were always the prey of the Macedonians, you tremble before Pyrrhus, who always, like a servant, followed some of Alexander's bodyguards, and now wanders through Italy, not to help the Greeks here, but to escape from his enemies there. couldn't hold on to himself and a small part of Macedonia! Do not think that by becoming friends with him, you will get rid of him, you will only open the way for those who will despise us in the belief that it is not difficult for anyone to subdue us, since Pyrrhus left without paying for his impudence, and even took away the reward , making the Romans a laughingstock for the Tarentines and Samnites." This speech by Appius inspired the senators with the determination to continue the war ... "(Pyrrhus, 18-19, translated by S. A. Osherov).

Final conquest of Italy

The victory over Pyrrhus untied the hands of Rome. The final conquest of southern Italy was no longer a difficult problem. In the year of Pyrrhus' death, Tarentum was besieged by Roman troops. Discord began between the Epirus garrison and the citizens. The pro-Roman party, representing mainly the interests of the nobility, was ready to surrender the city; the head of the garrison resisted for some time, but, seeing that the situation was hopeless and desiring to buy himself the right of free retreat by capitulation, he himself entered into relations with the Roman commander and surrendered the city. The garrison was allowed to sail freely to Epirus (272). Tarentum entered the Roman federation as a maritime ally, but with reduced autonomy. A Roman detachment was placed in the city fortress, and Tarentum became the main stronghold of Roman influence in southern Italy.

With the rights of the same naval allies, obliged to supply warships for Rome with appropriate weapons and crew, other Greek cities of the south were annexed: Croton, Locri, Furii, Velia, etc. The Campanian garrison in Regia, which turned into a band of robbers, was liquidated in 270 Roman troops stormed the city, most of the Campanians were killed, and 300 people captured alive were taken to Rome, carved on the forum and beheaded. The city was handed over to its former inhabitants, and it entered the federation with the right of a maritime ally and with full autonomy.

The South Italian tribes, who compromised themselves by going over to the side of Pyrrhus, suffered greatly. Some of their lands were taken from the Samnites, Lucans and Bruttians. Roman or Latin colonies were founded at strategically important points: Benevent, Paestum (Posidonia), later Brundisium (in the region of the Messapians).

The end of the war in southern Italy gave Rome an opportunity to complete what had not yet been completed in the north. Several strong colonies were founded in Etruria, Umbria and the former region of the Senones (ager Gallicus). Among them, one should especially note the Latin colony in the city of Arimina, on the northern tip of ager Gallicus. It was intended to protect the border of Roman Italy, which ran along the river. Rubicon.

One curious episode belongs to the period of Rome's final conquest of Italy, unfortunately preserved by our tradition in a very distorted form. It slightly lifts the veil over the secret social system of Etruria at the beginning of the 3rd century. During the Samnite Wars, the aristocracy of the city of Volsinia freed their slaves and included them in the army that acted against Rome. These freedmen seized power in the city, created a democratic system there and married the daughters of their former masters. The latter in 265 turned to Rome with a request for help. Upon learning of this, the freedmen attacked the masters: some of them were killed, some were expelled. The Romans rushed to the rescue. Volsinii were taken by storm and destroyed to the ground. Instead, they built new town(New Volsinia - on the northern shore of Lake Vadimon, not far from the old one), where the surviving masters and the slaves who remained faithful to them settled. The former social structure was completely restored.

The story, despite the many unreliable details, is generally interesting in that it characterizes the acuteness of social contradictions in Etruria already at the beginning of the 3rd century BC. But, apparently, the slaves that the sources speak of were hardly such in the exact sense of the word. We are talking here about a peculiar state of primitive dependence, outwardly reminiscent of serfdom, many analogies of which we find in Greece: Spartan helots, Thessalian penestes, etc. If the sources call this state slavery, it is only because neither Latin nor Greek languages have a term to denote the concept of "serf".

Causes of Rome's victory in the struggle for Italy

So, in the struggle for Italy, which lasted about three centuries, the small community on the Tiber turned out to be the winner. By the 60s. 3rd century all of Italy during the Republic, from r. Rubicon to the Strait of Messana, entered into a kind of federation headed by Rome. This was a fact of world-historical significance, the consequences of which proved to be incalculable, for the Italian alliance proved to be an extremely viable organism, capable of measuring its strength with the most powerful powers of the Mediterranean. What were the reasons that, in the struggle for dominance in Italy, determined the victory of Rome, and not some other community? Rome was far from being the most powerful policy when, even in the tsarist period, it began its endless wars with its neighbors. But the combination historical conditions, among which he arose and developed, was more favorable for him than for others, and above all the situation on the Lower Tiber. In the Roman community, from the very beginning, two points united: commercial and agricultural. The development of trade was facilitated by the position on the Tiber, the proximity of the sea, the extraction and transportation of salt, the proximity of Etruria and Campania; agrarian character was given to Rome by the fertile plain of Latium. The combination of these two moments was of great importance.

The lower Tiber was a crossroads of diverse influences, a center of interaction between various forces - economic, ethnic and cultural. Comparative historical material proves that in history the leading role has always belonged to those points that lay at the intersection of several lines of interaction. The development of exchange, borrowing from neighbors, tribal crossings, the benefits of a strategic position - all this led to the fact that these centers became the most powerful centers of historical development.

Rome, due to its location, very early began to attract people from the surrounding areas. The most enterprising and energetic elements flocked to it, which left a noticeable mark in the formation of the Roman national character. This character we can by no means discount in explaining the successes of Rome. It combined a strong dose of small-scale agrarian conservatism with traits of bold daring coming from pirates, merchants and adventurers.

However, despite this, the Roman community retained the features of relative primitiveness. The agrarian stream prevailed in it. It especially intensifies in the 5th century, when ties with the Etruscans were severed, and the Etruscan trade itself began to decline due to the growing competition between Sicily and Carthage. Compared with the policies of Etruria, Campania and Southern Italy, social contrasts in Rome were less pronounced, the whole system of life was much simpler. This gave Rome great advantages over its wealthy, pampered, socially strife-torn neighbors. Characteristic, for example, is the fact that many opponents of Rome were forced to turn to mercenaries, while the Roman army consisted of a citizen militia, which had a huge advantage over mercenary contingents in terms of its moral and political level. Only the tribes of Central Italy (the Samnites and others) were equal to Rome in this respect. But the Romans had an advantage over them in organization.

The Roman social system gave rise to the harsh and simple features of the popular character of the era of the struggle for Italy, reflected in the images of statesmen and generals. Of course, later legend greatly embellished them. But even through a thick layer of poetic inventions and patriotic falsifications, we can still see the true faces of Marcus Furius Camillus, Titus Manlius Torquatus, three Decii belonging to three different generations, Appius Claudius Caeca, Quintus Fabius Rullianus, Manius Curius Dentatus, Gaius Fabricius Luscinus and many others, whose labors and deeds laid the foundation of Roman greatness in this remarkable era.

Rome's central position in Italy gave it a great strategic advantage, allowing it to operate along internal operational routes and defeat its enemies one by one (with rare exceptions - for example, the battle of Sentin).

The unity of the will of Rome and, at the same time, the heterogeneity of the interests of its opponents also played a significant role. What could be in common between the Gauls and the Etruscans, the Samnites and the Greeks, the Italics and the hired troops of Pyrrhus? Nothing but a general hatred of Rome. But this was not enough to win: the Gauls and Etruscans quarreled over booty, the Tarentines did not trust Pyrrhus, the Greeks hated the Lucans and Bruttians. And next to this is the consistent policy of the Senate, which knew what it wanted, knew how to achieve its goals, wait patiently, make concessions if necessary, attack again, separate its enemies, bribing some, inflicting crushing blows on others.

Finally, Roman military equipment, finally developed by the 3rd century BC. (Roman manipulative system, a system of fortified camps, throwing weapons), turned out to be higher than even the Hellenistic technique of Pyrrhus. True, the phalanx, cavalry and elephants won at first. But when the Romans learned to frighten the elephants and learned the weaknesses of the phalanx, the famous commander was defeated by rude "barbarians".

These were the main reasons for the victory of Rome in the struggle for Italy.

Notes:

For a detailed historical and philological analysis of the inscription, see: Peruzzi E. On the Satricum inscription // La parola del passato, fasc. CLXXXII, Napoli, 1978, pp. 346-350; Fedorova E. V. An introduction to Latin epigraphy. M., 1982. S. 45-46.

Wed: Werner R. Der Beginn der romischen Republik. Munchen, 1963.

Last H. The Servian Reform // JRS, 35, 1945. P. 30-48.

This concept is most fully expressed in the following works: De Francisci P. Primordia civitatis. Roma, 1959; Heurgon J. The Rise of Rome...; Richard J.-Cl. 1) Les origines...; 2) Patricians and Plebeians: The Origin of a Social Dichotomy//Social Struggles in Archaic Rome. Los Angeles, 1986. P. 105-129; Gjerstad E. Innenpolitische und militarische Organization... S.136-188.

From the post-war reviews of various points of view on this issue, we highlight: Staveley E.S. Forschungsbericht: The Constitution of the Roman Republic// Historia, 5, 1956. P. 74-119; ScullardH. H A History of the Roman World... P. 460-461. See also the review of historiography in the fundamental article by A. I. Nemirovsky “On the question of the time and significance of the centuriate reform of Servius Tullius” (VDI, 1959, No. 2, p. 153 -165).

It is possible that this was one of the old Latin federations, which had grown stronger by this time.

The conclusion of the alliance was preceded by a war between the Romans and the Latins, which ended in the semi-legendary battle at Lake Regilla (499 or 496).

With the exception of Capena and Falerii, which were north of Veii. They provided Weii with active support. For this, Rome paid them off after the fall of Veii: in 395 Capena, in 394 Falerius were forced to recognize Roman domination. Expanding its influence in Southern Etruria, Rome in the late 90s. subjugated Sutry, Nepeta and even Volsinia - the sacred city of the Etruscans.

This fact is confirmed archaeologically.

Perhaps he had this nickname even before the Gauls, simply because he lived on the Capitol.

The Roman pound was approximately 4/5 of the Russian pound. The ransom sum of 1,000 pounds seems too large for that era and is probably exaggerated by Roman annalistics.

The main city of the Faliscan tribe, probably related to the Latins.

Tuskul, Ardea, Aricia, Lanuvius, Lavinius, Bark, Norba, etc.

In science, there is another point of view, according to which in 358 a new agreement was concluded, in particular with the communities of South Latium.

This point mattered not so much for Rome, whose commercial interests at that time could not extend so far, but for its old ally, the Greek colony of Massilia (now Marseille).

The Greeks called these Samnites Osci.

IV Netushil believes that in 343 the Capuan aristocracy entered into an alliance with Rome. But shortly thereafter, a coup took place in Capua, and the democracy that had seized power broke with the Romans.

Livy (VIII, 8), modernizing relations in the 4th century, writes: “This struggle was very similar to a civil war: to such an extent there was no difference between the Latin and Roman orders, with the exception of only courage.”

Consul Caecilius Metellus.

Pyrrhus believed that he had special rights to this latter as the husband of the daughter of the Sicilian tyrant Agathocles.

Since that time, the expression "Pyrrhic victory" has become a household word.

The tradition of the war with Pyrrhus is in a very bad state. It has been preserved mainly by later or minor writers and is extremely fragmentary and contradictory. Only the biography of Pyrrhus, owned by Plutarch, gives a coherent and detailed story. Therefore, the sequence of events cannot always be established with complete reliability. In particular, peace negotiations took place, according to one version of the legend, in 280, according to another - in 279. We have adopted the first version.

In the scientific literature, it has been suggested that there were other points in the agreement, perhaps secret, for example, financial assistance from Carthage to Rome.

The beginning of the use of the term “Italy” itself in relation to almost the entire peninsula dates back to this particular era, while initially the Greeks called Italy (from Oska Viteliu - actually “country of calves”) only the southwestern tip of the peninsula. Then the name was transferred to the whole of southern Italy and, finally, to the entire peninsula (except for the Po valley). Only Emperor Augustus also included the Po Valley in the borders of Italy.

The struggle of the patricians and plebeians in Rome was not antagonistic, that is, a class struggle in the exact sense of the word, despite its sometimes violent nature. Rather, it was a struggle between factions of the emerging slave-owning class. This explains the fact that in the face of a common enemy, both classes, as a rule, united. The foregoing, of course, does not exclude the possibility that in the struggle of the plebeian poor who were turned into debtor slaves, there were elements of a genuine class struggle.

During this period, Rome was predominantly an agricultural country. Depending on the area, wheat, barley, millet, beans, and turnips were grown. It was the lack of land for agriculture that was the main reason for the wars of conquest and the organization of colonies.

IN mountainous areas Rome was developed cattle breeding. They raised pigs, goats, sheep, cattle and horses.

In addition, references to goldsmiths, carpenters, shoemakers, potters and other artisans date back to this period of time. Archaeologists find specimens indicating advanced levels of spinning, weaving and metalworking.

The Temple of Jupiter and the bridge over the Tiber are among the significant creations of the architecture of that time.

The development of agriculture, cattle breeding and handicrafts contributed to regular internal exchange. The decree of Romulus on holding market days serves as confirmation of this.

The heyday of the Roman Empire, Republican (6th century BC - 1st century AD)

During this period, agriculture, cattle breeding and handicrafts continue to develop. However, in the process of social change, the labor of slaves practically replaces the labor of free people.

- On the one hand, this significantly reduces the cost of producing food and handicrafts, and there are more and more of them.

- On the other hand, their quality is lower than in or in the Middle East.

Between the cities of the Roman Republic, specialization in agriculture and crafts developed. For example, Capua was famous for its bronze and lead products, Puteoli for weapons, and Rome itself for leather and textile products.

The trading system has also expanded. Trade was conducted with Egypt, the countries of Asia Minor, Greece and Iberia. The opened sea routes were preferable to land routes, because they were cheaper. But the developed network of Roman roads created during this period remains a phenomenon to this day. However, due to the comparatively poor quality of Roman goods, imports dominated exports.

The expansion of trade required the minting of national money, as opposed to the Greek coins that were in circulation. This happened in the second half of the 4th century BC, when the denarius and sestertia came into circulation. There was usury in Rome during this period, with interest rates as high as 48 percent in some regions, leading to an increase in the number of slaves.

Period of crisis and decay, imperial (1st - 5th centuries AD)

The crisis affected all aspects of the economy of the Roman Empire. Despite the use of new technologies such as the water mill or the wheeled plow, farming gradually became unprofitable. In addition, the abundance of imported grain contributed to a greater decline in this area of activity.

By the 3rd century, it became clear that the labor of slaves was ineffective. In addition, the failures in military operations have sharply reduced the influx of new cheap labor.

Incentives for work among other segments of the population also decreased, and as a result, both craft and trade fell into decline.

I had to look for more effective ways management, but economic instability gradually led the Roman Empire to collapse.

Ancient Rome in the 1st century BC.

background

After the overthrow of the last Roman king Tarquinius the Proud (509/510 BC), an aristocratic republic was established in Rome. During the period of the republic, Rome unites all of Italy under its rule, and also conquers the Balkan Peninsula, Asia Minor, Syria, Spain, Gaul, and North Africa.

The desire of the people's tribunes to alleviate the lives of impoverished and landless citizens (who lost their land during military campaigns) led to the first civil clashes at the end of the 2nd century. BC.

In Rome, contradictions between supporters and opponents of the power of aristocratic families are growing more and more (supporters and opponents of the Senate as an expression of the power of patrician families enter the struggle).

Developments

90 BC- an uprising of the inhabitants of the Italic communities conquered by Rome, demanding that they be granted civil rights. By 88 B.C. almost the entire free population of Italy had Roman citizenship.

First third of the 1st c. BC.- a civil war between adherents of the Senate and supporters of reforms - opponents of an order in which power is concentrated in the hands of a few noble families.

83 BC- in the civil war between Lucius Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius, the supporter of the Senate Sulla wins.

82-79 BC- the dictatorship of Sulla, who himself appoints himself to the post of dictator for an unlimited period. Carries out mass repressions (composes proscriptions). In 79 BC resigned as dictator.

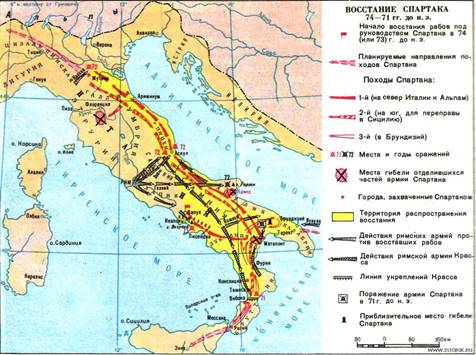

74-71 BC- the uprising of Spartacus, which was suppressed by the commander Mark Crassus ( about the uprising see video).

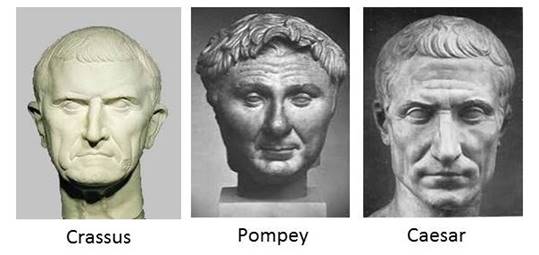

Middle of the 1st century BC.- the struggle for power between the three generals - Julius Caesar, who opposed the power of the Senate, Gnaeus Pompey and Mark Crassus.

58 BC- Julius Caesar becomes governor of the province of Gaul. Over the next years, he conquers the whole country (modern France), becoming the most popular commander and politician of Rome. This raises the fears of the senators, who endow Gnaeus Pompey with emergency powers.

49 BC- Caesar enters at the head of the troops into Italy, occupies Rome and subjugates all of Italy. Pompey and the Republicans mass their forces in Greece, but are defeated by Caesar.

49-44 years BC.- Caesar's dictatorship. For the first time in the history of Rome, Caesar was proclaimed (in 44 BC) dictator for life.

44 years BC.- Caesar is assassinated as a result of a conspiracy.

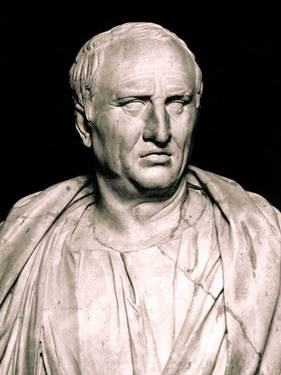

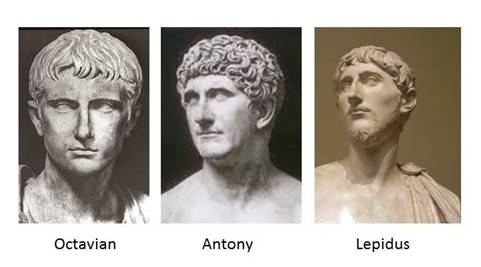

44-42 years BC.- civil war between Caesarians and Republicans. The Caesarians were led by Mark Antony, Aemilius Lepidus and Octavian. The famous orator Cicero was a supporter of the republic. The republican army was defeated, the beginning of the reign of Antony and Octavian, who actually divided the republic.

31 BC- Octavian defeats Mark Antony in the naval battle of Actium.

27 BC- Establishment of Octavian's principate. From the Senate, he receives the name Augustus ("exalted by the gods"). First Roman Emperor.

Members

Sulla Lucius Cornelius - Roman general and politician, dictator.

Caesar Gaius Julius - commander, politician, writer; dictator.

Cicero Mark Thulius - Roman orator, statesman, philosopher.

Augustus (Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian) - the first Roman emperor. He established a new form of government - the principate (from the Latin princeps - “first” in the Senate), concentrating power in his hands, but retaining republican institutions.

Conclusion

The battle of 31 BC between the troops of Antony and Octavian ended a series of civil wars. In Rome, sole power was established, Octavian Augustus became the first Roman emperor. In the history of ancient Rome, the period of the empire began (see lesson).

This lesson will focus on the history of Rome in the 1st century BC. e.

After the military reform, the role of generals in the Roman state increased. This happened very timely, since the Roman state at that time was in crisis. There were a lot of social groups with very different goals and objectives of their activities, so a common decision-making center was needed. This center could well become commanders.

The political struggle in Rome took place as a confrontation between the optimates and the populace.. Optimates were called supporters of the former, aristocratic, nature of government. They believed that such an order is the best, optimal, hence their name. Populars were people who believed that ordinary Roman citizens should be able to govern the Roman state, or at least influence politics. Populus bear their name from the word "populus" - the people.

The generals were both on the side of the optimates and on the side of the populi. What mattered to them was which group could grant them supreme power.

In 88 BC. e. people's tribune Sulpicius Rufus, who was on the side of the popular, proposed a bill that was supposed to change the way the state was governed. The composition of the Senate was changing: it was supposed to include an additional 300 people, which almost doubled the number of senators.

In addition, this project provided for the removal of a very popular commander from the leadership of the army. Sulla (Fig. 1). The army under the command of Sulla was to go to the East and fight there with the Pontic king MithridatesVIEvpator (Fig. 2).

Rice. 1. Roman commander Lucius Cornelius Sulla ()

Rice. 2. Bust of King Mithridates VI Eupator ()

Roman law strictly forbade entering the city with weapons. But Sulla led his troops into the city, they entered the Senate and forced the senators to reverse their decision. Sulla was solemnly restored to his rights and triumphantly sailed from the city to wage war with Mithridates VI Eupator.

The senators were unhappy that Sulla was interfering in political affairs. But to cope with Sulla in 88 BC. e. turned out to be impossible. However, as soon as he went to Asia, the Senate again decided to reform and deprived Sulla of his powers. But the senators did not take into account the fact that Sulla could return from a military campaign.

The war in Asia was not very long, but Sulla brought serious political results. During this war, the army of the Pontic king was defeated and an important city of Greece was taken - Athens (Fig. 3).

Rice. 3. Ancient Athens ()

In 85 BC. e. Sulla signed Peace of Dardan. According to the agreement, Mithridates VI Eupator renounced aggressive intentions, liberated the Roman provinces captured in Greece and Asia Minor, paid an indemnity of three thousand talents and transferred part of the fleet to Sulla.

In 82 BC. e. Sulla landed with his army in southern Italy. He fought his way to Rome.

The confrontation went on between supporters of government, where the commanders and opponents of such a regime were to play a decisive role. Sulla succeeded in coming to power in Rome, and he proclaimed himself dictator. For the first time, a Roman dictator was not elected, but appointed. Sulla himself appointed himself to this post, and not for half a year, but for an unlimited period. He demanded from Roman society and from the Senate that he be given emergency powers to deal with the social danger that existed in the city (in Rome at that time there was a full-fledged Civil War).

Sulla ordered lists of his political enemies posted throughout the city. These lists are called proscription. The people included in these lists were subject to the death penalty, and their property was to be confiscated in favor of Sulla.

As a result, Sulla became the richest man in Rome. Sulla also became the owner of a huge allotment of land. He did not keep these lands for himself, but distributed them among his soldiers. All areas around the capital were inhabited by veteran soldiers subordinate to Sulla.

From that moment until the very end of Roman history, not a single serious issue in Rome was decided without the participation of veterans. From that moment on, the generals became the most influential Roman politicians. Now the positions of officials were inextricably linked with the Roman army. If some problem or crisis was brewing, then the veterans would come to Rome and force the officials to make the decisions they supported.

Sulla remained dictator for a relatively short time. His powers were formally unlimited, but already in 79 BC. e. he took them off himself. He died the following year, and Sulla's dictatorship thus ended.

80-70s BC e. - an era when Rome wages numerous wars. The Roman army was no longer limited in numbers. Changes begin in the socio-economic life of society. Large-scale wars brought an increasing number of slaves to Rome. The more slaves there were, the lower their prices. The lower the prices in the markets, the worse the slaves were treated. This led to the fact that Rome began to shake slave uprisings.

At the same time, in the 70s BC. e., in Etrure happened Lipid's revolt. On the territory of modern Spain, there was a real Civil War between supporters and opponents of the generals. One of the slave uprisings took place on the island of Sicily. The Romans were most frightened uprising of Spartacus (Fig. 4), held in 74-71 years. BC e. It was not immediately possible to suppress this uprising. Its danger lay in the fact that the army of slaves was huge and the threat they posed to the city of Rome was very serious. Those commanders who managed to cope with Spartacus became the most popular Roman politicians of this time. These were Mark Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompey Magnus. It was they who in 70 BC. e. became Roman consuls (the position of consuls was occupied by two people at once so that none of them could usurp power).

Rice. 4. The uprising of Spartacus (map) ()

Senators didn't like it at all. An additional factor was that Pompey and Crassus came from plebeian families. The senators, descendants of the ancient patricians, looked down on them. But nothing could be done about it, because Crassus and Pompey did their job brilliantly.

For example, Pompey was instructed to end piracy. Piracy was a real tragedy mediterranean sea, and many tried to cope with it, but no one succeeded. Pompey solved this problem in just two months. He divided the entire Mediterranean Sea into 30 parts and sent part of the Roman fleet to each of these sectors. After 60 days, it was announced that there was no more piracy in the Mediterranean. Pompey so frightened the pirates that the problem did not return to Rome until the 2nd century AD. e. All this further strengthened the authority of Pompey.

There was no complete understanding between Pompey and Crassus. They saw each other as rivals. There were other commanders who wanted to gain power despite the fact that they did not have such merit as the victory over Spartacus.

So, in 63 BC. e. Rome faced the threat of the forcible establishment of a military dictatorship. If the power of Sulla was established as a result of the actions of his troops, then in 63 BC. e. there was a real political conspiracy. The politician (Fig. 5) tried to come to power. Catiline was not an outstanding commander who had an army devoted to him personally, and, unlike Sulla, he relied not on the active army, officially in service, but on “retires” and “volunteers”.

Another political figure began to actively fight against him - Mark Tullius Cicero (Fig. 6). The Catiline rebellion was quickly put down. As a result of the suppression of the rebellion, Cicero became one of the most popular Roman orators. But from a military point of view, Cicero was not as famous as Crassus or Pompey. The Roman people still continued to choose commanders.

Rice. 5. Lucius Sergius Catiline ()

Rice. 6. Mark Tullius Cicero ()

About 60 BC. e. Crassus and Pompey entered into an informal alliance with each other. They understood that the union of two commanders turns into a struggle between them, because everyone wanted to get sole power. But according to Roman law, this was impossible. They invited the third commander to join this union - Gaius Julius Caesar (Fig. 7). Thus, in 60 BC. e. an alliance was formed, which was called First Triumvirate (Fig. 8). Crassus, Pompey and Caesar became members of this Triumvirate.

Rice. 7. First Triumvirate (Crassus, Pompey and Caesar) ()

Rice. 8. Statue of Caesar in the garden of the Palace of Versailles ()

In 59 BC. e. Caesar becomes consul and, as one of the rulers of Rome, he pursues the policy that he had previously agreed with Crassus and Pompey. Now the Triumvirate decides for itself the question of who will run for consulship and who should hold power in Rome.