The main peak of the crisis of behaviorism, structural-functional analysis and other main methodological trends fell on the 60-70s. These years were full of attempts to find a new methodological basis for further research. Scientists have tried to do this in different ways:

1. update the "classical" methodological approaches (the emergence of post-behavioral methodological trends, neo-institutionalism, etc.);

2. create a system of "middle level" theories and try to use these theories as a methodological basis;

3. try to create an equivalent general theory by referring to classical political theories;

4. turn to Marxism and create on the basis of this various kinds of technocratic theories.

These years are characterized by the emergence of a number of methodological theories that claim to be the "grand theory". One of such theories, one of such methodological directions was the theory of rational choice.

Rational choice theory was designed to overcome the shortcomings of behaviorism, structural-functional analysis and institutionalism, creating a theory of political behavior in which a person would act as an independent, active political actor, a theory that would allow looking at a person’s behavior “from the inside”, taking into account the nature of his attitudes, choice of optimal behavior, etc.

The theory of rational choice came to political science from economics. The “founding fathers” of the theory of rational choice are considered to be E. Downes (he formulated the main provisions of the theory in his work “The Economic Theory of Democracy”), D. Black (introduced the concept of preferences into political science, described the mechanism for their translation into performance results), G. Simon (substantiated the concept bounded rationality and demonstrated the possibility of using the rational choice paradigm), as well as L. Chapley, M. Shubik, V. Riker, M. Olson, J. Buchanan, G. Tulloch (they developed "game theory"). It took about ten years before rational choice theory became widespread in political science.

Proponents of rational choice theory proceed from the following methodological assumptions:

First, methodological individualism, that is, the recognition that social and political structures, politics, and society as a whole are secondary to the individual. It is the individual who produces institutions and relationships through his activity. Therefore, the interests of the individual are determined by him, as well as the order of preferences.

Secondly, the selfishness of the individual, that is, his desire to maximize his own benefit. This does not mean that a person will necessarily behave like an egoist, but even if he behaves like an altruist, then this method is most likely more beneficial for him than others. This applies not only to the behavior of an individual, but also to his behavior in a group when he is not bound by special personal attachments.

Supporters of the theory of rational choice believe that the voter decides whether to come to the polls or not, depending on how he evaluates the benefits of his vote, and also votes based on rational considerations of utility. He can manipulate his political settings if he sees that he may not get a win. Political parties in elections also try to maximize their benefits by enlisting the support of as many voters as possible. Deputies form committees, guided by the need to pass this or that bill, their people to the government, and so on. The bureaucracy in its activities is guided by the desire to increase its organization and its budget, and so on.

Thirdly, the rationality of individuals, that is, their ability to arrange their preferences in accordance with their maximum benefit. As E. Downes wrote, "every time we talk about rational behavior, we mean rational behavior, initially directed towards selfish goals." In this case, the individual correlates the expected results and costs and, trying to maximize the result, tries to minimize costs at the same time. Since the rationalization of behavior and the assessment of the ratio of benefits and costs require the possession of significant information, and its receipt is associated with an increase in overall costs, one speaks of "limited rationality" of the individual. This bounded rationality more associated with the decision-making procedure itself, rather than with the essence of the decision itself.

Fourth, the exchange of activities. Individuals in society do not act alone, there is an interdependence of people's choices. The behavior of each individual is carried out in certain institutional conditions, that is, under the influence of institutions. These institutional conditions themselves are created by people, but the initial one is people's consent to the exchange of activities. In the process of activity, individuals rather do not adapt to institutions, but try to change them in accordance with their interests. Institutions, in turn, can change the order of preferences, but this only means that the changed order turned out to be beneficial for political actors under given conditions.

Most often, the political process within the framework of the rational choice paradigm is described in the form of public choice theory, or in the form of game theory.

Proponents of the theory of public choice proceed from the fact that in the group the individual behaves selfishly and rationally. He will not voluntarily make special efforts to achieve common goals, but will try to use public goods for free (the “hare” phenomenon in public transport). This is because the nature of a collective good includes such characteristics as non-excludability (that is, no one can be excluded from the use of a public good) and non-rivalry (the consumption of this good by a large number of people does not lead to a decrease in its utility).

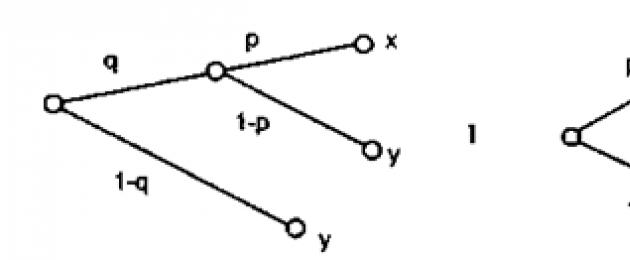

Game theorists assume that the political struggle to win, as well as the assumptions of rational choice theory about the universality of such qualities of political actors as selfishness and rationality, make the political process similar to a game with zero or non-zero sum. As is known from the course of general political science, game theory describes the interaction of actors through a certain set of game scenarios. The purpose of such an analysis is to search for such game conditions under which participants choose certain behavior strategies, for example, that are beneficial to all participants at once.

This methodological approach is not free from some shortcomings. One of these shortcomings is the insufficient consideration of social and cultural-historical factors influencing the individual's behavior. The authors of this study guide are far from agreeing with researchers who believe that the political behavior of an individual is largely a function of social structure or with those who argue that the political behavior of actors is in principle incomparable, because it takes place within unique national conditions, and so on. However, it is clear that the rational choice model does not take into account the influence sociocultural environment on the preferences, motivation and strategy of behavior of political actors, the influence of the specifics of political discourse is not taken into account.

Another shortcoming has to do with the assumption of rational choice theorists about the rationality of behavior. The point is not only that individuals can behave like altruists, and not only that they can have limited information, imperfect qualities. These nuances, as shown above, are explained by the rational choice theory itself. First of all, we are talking about the fact that often people act irrationally under the influence of short-term factors, under the influence of affect, guided, for example, by momentary impulses.

As D. Easton rightly points out, the broad interpretation of rationality proposed by the supporters of the theory under consideration leads to the blurring of this concept. More fruitful for solving the problems posed by the representatives of rational choice theory would be to single out types of political behavior depending on its motivation. In particular, “social-oriented” behavior in the interests of “social solidarity” differs significantly from rational and selfish behavior.

In addition, rational choice theory is often criticized for some technical inconsistencies arising from the main provisions, as well as for the limited explanatory possibilities (for example, the applicability of the model of party competition proposed by its supporters only to countries with a two-party system). However, a significant part of such criticism either stems from a misinterpretation of the work of representatives of this theory, or is refuted by the representatives of rational choice theory themselves (for example, with the help of the concept of "bounded" rationality).

Despite these shortcomings, rational choice theory has a number of virtues which are the reason for its great popularity. The first undoubted advantage is that standard methods are used here. scientific research. The analyst formulates hypotheses or theorems based on a general theory. The method of analysis used by supporters of rational choice theory proposes the construction of theorems that include alternative hypotheses about the intentions of political actors. The researcher then subjects these hypotheses or theorems to empirical testing. If reality does not disprove theorems, that theorem or hypothesis is considered relevant. If the test results are unsuccessful, the researcher draws the appropriate conclusions and repeats the procedure again. The use of this technique allows the researcher to draw a conclusion about what actions of people, institutional structures and the results of the exchange of activities will be most likely under certain conditions. Thus, rational choice theory solves the problem of verifying theoretical propositions by testing scientists' assumptions about the intentions of political subjects.

As the well-known political scientist K. von Boime rightly notes, the success of rational choice theory in political science can be generally explained by the following reasons:

1. “neopositivist requirements for the use of deductive methods in political science are most easily satisfied with the help of formal models, on which this methodological approach is based

2. The rational choice approach can be applied to the analysis of any type of behavior - from the actions of the most selfish rationalist to the infinitely altruistic activity of Mother Teresa, who maximized the strategy of helping the disadvantaged

3. directions of political science, which are on the middle level between micro- and macrotheories, are forced to recognize the possibility of an approach based on the analysis of activity ( political actors– E.M., O.T.) actors. The actor in the concept of rational choice is a construction that allows you to avoid the question of the real unity of the individual

4. rational choice theory promotes the use of qualitative and cumulative ( mixed - E.M., O.T.) approaches in political science

5. The rational choice approach acted as a kind of counterbalance to the dominance of behavioral research in previous decades. It is easy to combine it with multi-level analysis (especially when studying the realities of the countries of the European Union) and with ... neo-institutionalism, which became widespread in the 80s.

Rational choice theory has a fairly wide scope. It is used to analyze voter behavior, parliamentary activity and coalition formation, international relations etc., is widely used in modeling political processes.

This paragraph has in its title the phrase social production. Why was this epithet needed Is the concept of production not enough to clarify the need for the interaction of the main factors of production? Even an individual craftsman or farmer, believing that he acts completely independently of anyone else, is in fact connected by thousands of economic threads with other people. It can also be noted here that the Robinsonade method, when an individual person (one of the most widely used research methods in ) living on a desert island, is considered as an example, does not contradict the statement about the social nature of production. Robinsonade helps to better understand the mechanism of rational economic behavior of an individual, but this mechanism does not cease to operate if we move from the Robinson model to the realities of not individual, but public choice. It may seem that only macroeconomics is connected with the study of social production, while microeconomics deals only with individual economic individuals. Indeed, in the study of microeconomics, we will most often have to use the individual producer or consumer as an example. But at the same time, it must be remembered that the mentioned subjects operate in a system of restrictions imposed by public institutions (for example, the institution of property, morality, and other formal and informal rules).

The rational use of limited economic resources in order to most fully meet the needs of the individual, households, and other economic entities is manifested primarily in, which should be considered the identical theory of the equilibrium of the individual and the household in consumption. It explores such conditions and rules of consumer behavior in a market economy that ensure the achievement of the main goal - increasing their level of well-being in the face of growing needs. The conclusions and provisions of the theory of consumer choice allow answering questions related to the rationalization of the use of income by an individual and a household, as well as other limited resources. In modern economic theory, there are two approaches to identifying the patterns of economic behavior of a person who seeks to maximize the parameters of his consumption and, consequently, well-being.

The second, institutional approach to the problem of consumer choice, on the one hand, concretizes neoclassical "idealism", and on the other hand, introduces qualitatively new approaches to the study of the economic behavior of individuals. In general, abstract-logical constructions are being replaced by no less complex, but more realistic postulates and justifications for the rational behavior of consumers. The institutional approach to the problem of consumer choice is formed from the concepts of the "old" in-

We paid more attention to the economic way of thinking. In Chapter 1, we significantly expanded the section on the economic approach to reality, dealing in detail with the problems of scarcity of resources and choice, rational behavior, and marginal analysis. In Chapter 2, we use the concepts of marginal benefit and marginal cost (see Figure 2-2) to determine the optimum position for an economy on the production possibilities curve. And later, in the rest of the textbook, we do not miss the opportunity to recall the economic approach.

Let us now return to the problem of making decisions that allow individuals acting as consumers, within the limits of their income, to choose the most preferable set of goods and services for themselves. From an economic point of view, consumer behavior is rational if the option chosen by him allows him to get maximum satisfaction from the purchased set of goods and services. On the basis of the hypothesis about the rationality of consumer behavior, the theory of consumer choice is constructed.

The fundamental premise of economic man is that all people know the alternatives available in a given situation and all the consequences that they will cause. It also assumes that people will behave rationally, that is, they will make choices that maximize some value. Even today, most microeconomic theories are based on the assumption of profit maximization. Obviously, it is wrong to assume that people always behave in a rational way. G. Simon believed that an administrative person is a more accurate model of reality, since managers were never fully informed and were rarely able to maximize anything. Due to the physical limitations of decision makers, Simon introduced the principle of bounded rationality. Since the optimization looks for administrative person too difficult, Simon suggested that satisfaction is a more realistic and typical procedure. The satisfaction seeker considers possible alternatives until he finds one that meets the minimum standard of satisfaction. Although many new quantitative methods give managers a better understanding of the situation in which the decision is made, studies of real decision-making behavior have reinforced this theory.

IGOR. And when it comes to redistribution, it is necessary to find a balance between the interests of those who receive and those who give. This means that the logic of the behavior of the state is the logic of public choice, which, unlike the individual, is made jointly, moreover, with the help of political institutions. Economic theory studies social choice from its own specific point of view, considering it as the result of the actions of rational individuals. Of course, economic analysis primarily emphasizes the similarities and

Finally, it should be said about approaches to studying the behavior of voters. In terms of the rational choice model, voters will vote only if the expected benefits outweigh the expected costs. The size of the expected benefits is multiplied by the product of the welfare gain that the voter will receive as a result of the victory of the party announcing the most favorable course of economic policy for him, by the probability that it is the vote of this voter that will have a decisive influence on the outcome of the election (an additional factor can be the voter's subjective assessment of the probability that that the party will keep its campaign promises). Since the probability of casting a decisive vote in most cases is not

He concluded his Nobel lecture with these words. I am impressed by how many economists are showing a desire to study social issues, rather than those that traditionally formed the core of economics. At the same time, the economic mode of modeling behavior often attracts, by its analytical power, which the principle of individual rationality provides it, specialists from other fields who study social problems. Influential schools of rational choice theorists and empiricists are active in sociology, jurisprudence, political science, history, anthropology, and psychology. The rational choice model provides the most promising

Among the numerous models of human behavior in the modern economy, there are several of the most well-known and genetically related. First of all, this is the model of behavior of the "economic man", according to which each individual, having the freedom of economic choice, seeks to satisfy individual needs through rational behavior. This model was created by the classical and neoclassical school of economics and dominated until the middle of the 20th century. The essence of this model lies in the desire of each person, who freely disposes of his resources, to achieve the maximum possible benefit from their use. The subjective basis of this model is a person as an individual, and the object structure of the created and consumed goods is represented mainly by material and material products of labor activity.

Within the framework of the "economic man" behavior model, one can single out the neoclassical concept of shelf or absolute rationality, as well as the neo-institutional concept of limited or satisfactory rationality. The essence of the concept of absolute rationality lies in the fact that an individual consciously striving for the best economic choice receives the highest positive economic income from all possible alternatives. This is achieved through the competent use of information that is directly and indirectly related to the solution of economic problems. The disadvantage of the concept of complete rationality is the excessive abstraction and abstraction of researchers from socio-economic realities.

In addition, the desire of an individual to make the best economic choice and the related search and processing of the necessary information are always carried out in a certain institutional environment, under the conditions of formal and informal norms and rules. An individual striving to rationalize his economic activity is in a system of socio-economic and other relationships with other individuals. It is in their common interests to streamline, i.e., institutionalize the system of relations with each other, which is impossible without "permissions" and "prohibitions" accepted and observed by all for quite definite decisions and actions. Thus, such behavior of an "economic man" becomes rational, which is associated with the search not for the theoretically best, but practically the most preferable, or satisfactory, option for an economic choice.

The subjectivist approach to the study of economic relations analyzes the behavior of a particular individual, and not an economic entity as such, which can be a firm, a state, etc. theory is reduced to the description of human activity, determined by the boundaries individual needs. The model of human behavior in the economy is identified here with the model of behavior of "economic man", and the basic concepts are "needs", "utility", "economic choice", etc. Economic theory itself is identified here with theories of rational human behavior when using limited resources.

The fourth feature concerns the calculation of results, consequences - the effectiveness of behavior. Activities are judged on their effectiveness, i.e. by result. In this sense, the goal of an activity is its result. Decision-making refers to the evaluation of alternatives, the calculation of consequences, the choice of a course of action based on the relative value of the expected result. It is assumed that both the means and the ends themselves are chosen in this way. If the achievement of the goal requires too much risk and / or cost, then, as economists believe, the economic person is called from the goal. Therefore, the rationality of economic behavior is understood as a calculation (of goals, means, results) and a sequence of these steps.

The problem of choice in its neoclassical version can be looked at in two ways. So, from the point of view of limited resources, it looks like an optimization of the behavior of an economic agent. On the other hand, choice is an attribute of a free individual, free, according to at least from personal addiction. Being one of the initial premises of classical and neoclassical economic theory, the problem of choice has undergone a bifurcation, its sides began to exist separately. This was the basis for the emergence of two different research trends, based on different foundations, one on the premise of freedom of choice, the other on the premise of rational choice, although both tendencies can formally preserve both of them. In economic theory itself, what is now formed is what is called orthodox or general economic theory, the "mainstream", in the methodological core of which one of the main places is given to the principle of rationality of individual choice, which was subsequently criticized by neo-institutionalists and representatives of the new institutional economics.

The founders of the institutional school (T.Veblen, J.Commons, J.M.Clark, W.Mitchell, W.Hamilton, etc.) considered institutions as patterns and norms of behavior, as well as habits of thinking that influence the choice of strategies for economic behavior in addition to the motivation of rational economic choice. Unlike the old institutionalists, supporters of the neo-institutional direction O. Williamson, R. Coase, D. North and others give the concept of an institution a broader meaning, considering them as the most important factors in economic interactions and, accordingly, building a system of other categories on this concept. We join the interpretation according to which institutions are the rules of the game in society, or, more formally, man-made restrictive frameworks that organize relationships between people. Therefore, they set the structure of the motives for human interaction - be it in politics,

| Whether or not this publication is taken into account in the RSCI. Some categories of publications (for example, articles in abstract, popular science, informational journals) can be posted on the website platform, but are not counted in the RSCI. Also, articles in journals and collections excluded from the RSCI for violation of scientific and publishing ethics are not taken into account. "> Included in the RSCI ®: yes | The number of citations of this publication from publications included in the RSCI. The publication itself may not be included in the RSCI. For collections of articles and books indexed in the RSCI at the level of individual chapters, the total number of citations of all articles (chapters) and the collection (book) as a whole is indicated. "> Citations in the RSCI ®: 47 |

| Whether or not this publication is included in the core of the RSCI. The RSCI core includes all articles published in journals indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus or Russian Science Citation Index (RSCI) databases."> Included in the RSCI ® core: Yes | The number of citations of this publication from publications included in the RSCI core. The publication itself may not be included in the core of the RSCI. For collections of articles and books indexed in the RSCI at the level of individual chapters, the total number of citations of all articles (chapters) and the collection (book) as a whole is indicated. |

| The citation rate, normalized by journal, is calculated by dividing the number of citations received by a given article by the average number of citations received by articles of the same type in the same journal published in the same year. Shows how much the level of this article is higher or lower than the average level of articles of the journal in which it is published. Calculated if the journal has a complete set of issues for a given year in the RSCI. For articles of the current year, the indicator is not calculated."> Normal citation for the journal: 1,639 | Five-year impact factor of the journal in which the article was published for 2018. "> Impact factor of the journal in the RSCI: 1.322 |

| The citation rate, normalized by subject area, is calculated by dividing the number of citations received by a given publication by the average number of citations received by publications of the same type in the same subject area published in the same year. Shows how much the level of this publication is above or below the average level of other publications in the same field of science. For publications of the current year, the indicator is not calculated."> Normal citation in the direction: 39,81 |