What Linnaeus did and what contribution he made to science, you will learn in this article.

Carl Linnaeus's contribution to science in brief

The scientist of the pre-Darwinian period of biology, Carl Linnaeus, an outstanding botanist, naturalist and naturalist, made important discoveries in the field of biology.

With his main work entitled “System of Nature,” published in 1735, Linnaeus made a significant contribution to the development of biology - he introduced the world to a progressive system of the organic world at that time.

The merits of Carl Linnaeus are as follows:

- The scientist was the first to establish the reality of species, their universality, and also identified main feature- This is free crossing between individuals of the same species.

- Linnaeus introduced its basic units into taxonomy: species - genus - family - order - class.

- He is the creator of the system of the organic world, according to which all plants were divided into 24 classes - 23 classes of flowers and one class of spores and gymnosperms. Of the flower classes, Carl Linnaeus identified 12 classes based on the number of stamens; the 13th class united plants that have more than 12 stamens. But classes 14 – 23 were also characterized by the structure of the androecium. In the animal world, he identified 6 classes: insects, worms, reptiles, birds, fish and mammals.

- Another contribution of Linnaeus to the development of biology was the introduction of binary, double nomenclature instead of the current system of verbose, cumbersome names. It indicated that the organism belonged to a separate genus and species.

- Scientists have described more than 10 thousand species of plants and more than 4.5 thousand species of animals.

- As a botanist, he was able to improve the botanical language. They identified about 1000 terms.

- He was the first to place humans in the same order as apes, based on their morphological similarities.

Based on these achievements, the Swedish naturalist and scientist was rightly called the father of taxonomy. His scientific works brought biology out of crisis and contributed to the accumulation of new, useful knowledge.

Linnaeus is the most famous Swedish natural scientist. In Sweden he is also valued as a traveler who discovered their own country for the Swedes, studied the uniqueness of the Swedish provinces and saw “how one province can help another.” The value for the Swedes is not so much Linnaeus’s work on the flora and fauna of Sweden as his descriptions of his own travels; These diary entries, filled with specifics, rich in contrasts, presented in clear language, are still reprinted and read. Linnaeus is one of those scientific and cultural figures with whom the final formation of the literary Swedish language in its modern form.

Karl was the first-born in the family (later Nils Ingemarsson and Christina had four more children - three girls and a boy).

In 1709, the family moved to Stenbruhult, located a couple of kilometers from Rosshult. There Nils Linnaeus planted a small garden near his house, which he lovingly tended; here he grew vegetables, fruits and various flowers, and knew all their names. From early childhood, Karl also showed interest in plants; by the age of eight he knew the names of many plants that were found in the vicinity of Stenbruhult; in addition, he was allocated a small area in the garden for his own small garden.

In 1716-1727, Carl Linnaeus studied in the city of Växjö: first at the lower grammar school (1716-1724), then at the gymnasium (1724-1727). Since Växjö was about fifty kilometers from Stenbruhult, Karl was only at home during the holidays. His parents wanted him to study to be a pastor and in the future, as the eldest son, to take his father’s place, but Karl studied very poorly, especially in the basic subjects of theology and ancient languages. He was only interested in botany and mathematics; Often he even skipped classes, going into nature to study plants instead of school.

Dr. Johan Stensson Rothman (1684-1763), a district doctor who taught logic and medicine at Linnaeus’s school, persuaded Niels Linnaeus to send his son to study as a doctor and began to study medicine, physiology and botany with Karl individually. The parents' concerns about Karl's fate were related, in particular, to the fact that finding work in Sweden for a doctor at that time was very difficult, while at the same time there were no problems with work for a priest.

Study in Lund and Uppsala

At the University of Uppsala, Linnaeus met his peer, student Peter Artedi (1705-1735), with whom they began work on a critical revision of the natural history classifications that existed at that time. Linnaeus was primarily concerned with plants in general, Artedi with fishes, amphibians and umbelliferous plants. It should be noted that the level of teaching at both universities was not very high, and most of the time students were engaged in self-education.

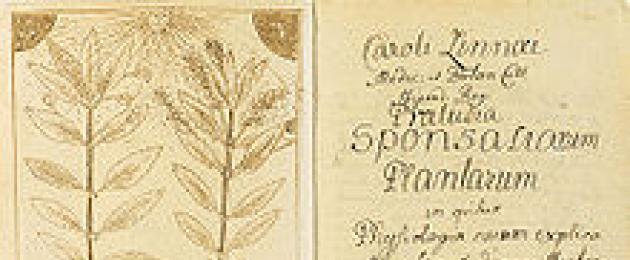

Manuscript of Linnaeus' work (December 1729)

In 1729, Linnaeus met Olof Celsius (1670-1756), a professor of theology who was a keen botanist. This meeting turned out to be very important for Linnaeus: he soon settled in the house of Celsus and gained access to his extensive library. In the same year, Linnaeus wrote a short work “Introduction to the Sexual Life of Plants” (lat. Praeludia sponsaliorum plantarum ), which outlined the main ideas of his future classification of plants based on sexual characteristics. This work aroused great interest in academic circles in Uppsala.

Since 1730, Linnaeus, under the supervision of Professor Olof Rudbeck Jr., began teaching as a demonstrator in the botanical garden of the university. Linnaeus's lectures were a great success. In the same year, he moved into the professor’s house and began serving as a home teacher in his family. Linnaeus, however, did not live in the Rudbecks’ house for too long, the reason for which was an unsuccessful relationship with the professor’s wife.

Known about educational excursions, which Linnaeus conducted during these years in the vicinity of Uppsala.

With another professor of medicine, Lars Ruberg, Linnaeus also developed a good relationship. Ruberg was a follower of Cynic philosophy, seemed a strange person, dressed poorly, but was a talented scientist and the owner of a large library. Linnaeus admired him and was an active follower of the new mechanistic physiology, which was based on the fact that all the diversity of the world has a single structure and can be reduced to a relatively small number of rational laws, just as physics is reduced to Newton's laws. The main postulate of this doctrine is “man is a machine” (lat. homo machina est), in relation to medicine, as presented by Ruberg, looked like this: “The heart is a pump, the lungs are a bellows, the stomach is a trough.” It is known that Linnaeus was an adherent of another thesis - “man is an animal” (lat. homo animal est). In general, such a mechanistic approach to natural phenomena contributed to the drawing of many parallels both between various areas of natural science and between nature and socio-cultural phenomena. It was on such views that the plans of Linnaeus and his friend Peter Artedi to reform the entire science of nature were based - their main idea was to create a single, ordered system of knowledge that would be easily reviewable.

|

|

| Linnaeus in “Lapland” (traditional Sami) costume (1737). Painting by Dutch artist Martin Hoffman ( Martin Hoffman). In one hand Linnaeus holds a shaman's drum, in the other - his favorite plant, later named after him - linnaea. Linnaeus brought the Sami costume, as well as the herbarium of the Lapland flora, along with the manuscript “Flora of Lapland” to Holland |

Having received funds from the Uppsala Royal Scientific Society, Linnaeus set out for Lapland and Finland on 12 May 1732. During his journey, Linnaeus explored and collected plants, animals and minerals, as well as a variety of information about the culture and lifestyle of the local population, including the Sami (Lapps). The idea of this trip largely belonged to Professor Olof Rudbeck the Younger, who in 1695 traveled specifically through Lapland (Rudbeck’s trip can be called the first scientific expedition in the history of Sweden), and later, based on materials collected in Lapland, he himself wrote illustrated a book about birds, which he showed to Linnaeus. Linnaeus returned to Uppsala in the fall, on October 10, with collections and records. The same year it was published Florula lapponica(“Brief Flora of Lapland”), in which the so-called “plant sexual system” of 24 classes, based on the structure of stamens and pistils, appears for the first time in print.

During this period, universities in Sweden did not issue doctor of medicine degrees, and Linnaeus, without a doctoral diploma, could not continue teaching in Uppsala.

In 1733, Linnaeus was actively involved in mineralogy and wrote a textbook on this topic. At Christmas 1733, he moved to Falun, where he began teaching assay art and mineralogy.

In 1734, Linnaeus made a botanical journey to the province of Dalarna.

Dutch period

On June 23, 1735, Linnaeus received his doctorate in medicine from the University of Harderwijk, defending his thesis prepared at home, “A New Hypothesis of Intermittent Fever” (on the causes of malaria). From Harderwijk Linnaeus went to Leiden, where he published a short work Systema naturae(“System of Nature”), which opened the way for him to the circle of learned doctors, naturalists and collectors in Holland, who revolved around the European-famous professor at Leiden University, Hermann Boerhaave (1668-1738). Linnaeus was helped with the publication of the System of Nature by Jan Gronovius (1686-1762), a doctor of medicine and botanist from Leiden: he was so delighted with this work that he expressed a desire to print it at his own expense. Access to Boerhaave was very difficult, but after the publication of “Systems of Nature,” he himself invited Linnaeus, and soon it was Boerhaave who persuaded Linnaeus not to leave for his homeland and to stay for a while in Holland.

In August 1735, Linnaeus, under the patronage of friends, received the position of caretaker of the collections and botanical garden of George Clifford (1685-1760), burgomaster of Amsterdam, banker, one of the directors of the Dutch East India Company and a keen amateur botanist. The garden was located on the Hartekamp estate near the city of Haarlem; Linnaeus was engaged in the description and classification of a large collection of living exotic plants delivered to Holland by company ships from all over the world.

Linnaeus's close friend Peter Artedi also moved to Holland; he worked in Amsterdam, organizing the collections of Albert Seb (1665-1736), traveler, zoologist and pharmacist. Unfortunately, on September 27, 1735, Artedi drowned in a canal after tripping while returning home at night. By this time, Artedi managed to finish his general work on ichthyology, and also identified all the fish from Seb’s collection and made their description. Linnaeus and Artedi bequeathed their manuscripts to each other, but for the handing over of the manuscripts to Artedi, the owner of the apartment in which he lived demanded a large ransom, which was paid by Linnaeus thanks to the assistance of George Clifford. Linnaeus later prepared his friend's manuscript for publication and published it in 1738 under the title Ichtyologia. In addition, Linnaeus used Artedi’s proposals for the classification of fish and umbrella plants in his works.

In the summer of 1736, Linnaeus traveled to England, where he lived for several months; he met famous botanists of the time, including Hans Sloan (1660-1753) and Johan Jacob Dillenius (1687-1747).

Carl Linnaeus

Genera plantarum, chapter ratio operis. § eleven.

The three years Linnaeus spent in Holland are one of his most fruitful periods. scientific biography. During this time, his main works were published: first edition Systema naturae(“System of Nature”, 1736), Bibliotheca Botanica(“Botanical Library”, 1736), Musa Clifortiana("Clifford's Banana", 1736), Fundamenta Botanica(“Principles of Botany”, “Principles of Botany”, 1736), Hortus Cliffortianus("Clifford's Garden", 1737), Flora Lapponica(“Flora of Lapland”, 1737), Genera plantarum(“Genera of Plants”, 1737), Critica botanica (1737), Classes plantarum("Classes of Plants", 1738). Some of these books came with wonderful illustrations by the artist George Ehret (1708-1770).

Returning to his homeland, Linnaeus never left its borders again, but three years spent abroad was enough for his name to very soon become world famous. This was facilitated by his numerous works published in Holland (since it quickly became clear that they, in a certain sense, laid the foundation of biology as a full-fledged science), and the fact that he personally met many authoritative botanists of that time (despite the fact that he cannot was called a secular man and he was bad at foreign languages) . As Linnaeus later described this period of his life, during this time he “wrote more, discovered more, and made more major reforms in botany than anyone else before him in his entire life.”

| Cybele (Mother Earth) and Linnaeus as young Apollo, raising right hand the veil of ignorance, in the left carrying a torch, the beacon of knowledge, and trampling with its left foot the dragon of lies. Hortus Cliffortianus(1737), frontispiece detail. Artwork by Jan Vandelaar |

The publication of such a large number of works was also possible because Linnaeus often did not follow the process of publishing his works; on his behalf, his friends did this.

Linnaeus family

In 1738, after Linnaeus returned to his homeland, he and Sarah officially became engaged, and in September 1739, their wedding took place in the Moreus family farm.

Their first child (later known as Carl Linnaeus Jr.) was born in 1741. They had a total of seven children (two boys and five girls), of whom two (a boy and a girl) died in infancy.

A genus of beautifully flowering South African perennials from the Iris family ( Iridaceae) was named by Linnaeus Moraea(Morea) - in honor of the wife and her father.

Genealogical chart of the Linnaeus family

| Ingemar Bengtsson 1633-1693 |

Ingrid Ingemarsdotter 1641-1717 |

Samuel Brodersonius 1656-1707 |

Maria (Marna) Jörgensdotter-Schee 1664-1703 |

Johan Moræus ~1640-1677 |

Barbro Svedberg 1649- ? |

Hans Israelsson Stjärna 1656-1732 |

Sara Danielsdotter 1667-1741 |

||||||||||||||

| Nils Ingemarsson Linnaeus Nicolaus (Nils) Ingemarsson Linnæus 1674-1748 |

Christina Brodersonia Christina Brodersonia 1688-1733 |

Johan Hansson Moreus Johan Hansson Moraeus (Moræus) 1672-1742 |

Elisabeth Hansdotter Elisabet Hansdotter Stjärna 1691-1769 |

||||||||||||||||||

| Carl Linnaeus Carl (Carolus) Linnaeus Carl von Linne 1707-1778 |

Sarah Lisa Morea Sara Elisabeth (Elisabeth, Lisa) Moraea (Moræa) 1716-1806 |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Carl von Linné d.y. (Carl Linnaeus Jr.

, 1741-1783) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

Linnaeus had three sisters and a brother, Samuel. It was Samuel Linnaeus (1718-1797) who succeeded Nils Ingemarsson Linnaeus, their father, as clergyman of Stenbruhult. Samuel is known in Sweden as the author of a book about beekeeping.

Mature years in Stockholm and Uppsala

Returning to his homeland, Linnaeus opened a medical practice in Stockholm (1738). Having cured several ladies-in-waiting's coughs with a decoction of fresh yarrow leaves, he soon became a court physician and one of the most fashionable doctors in the capital. It is known that in his medical work, Linnaeus actively used strawberries, both to treat gout and to cleanse the blood, improve complexion, and reduce weight. In 1739, Linnaeus, having headed the naval hospital, obtained permission to autopsy the corpses of the dead to determine the cause of death.

In addition to his medical activities, Linnaeus taught in Stockholm at a mining school.

In 1739, Linnaeus took part in the formation of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (which in the early years of its existence was a private society) and became its first chairman.

In October 1741, Linnaeus took up the post of professor of medicine at Uppsala University and moved to the professor's house, located in the University Botanical Garden (now the Linnaeus Garden). The position of professor allowed him to concentrate on writing books and dissertations on natural history. Linnaeus worked at Uppsala University until the end of his life.

In 1750, Carl Linnaeus was appointed rector of Uppsala University.

The most significant publications of the 1750s:

- Philosophia botanica(“Philosophy of Botany”, 1751) - a textbook of botany, translated into many European languages and remained a model for other textbooks until the beginning of the 19th century.

- Species plantarum(“Plant Species”). The date of publication of the work - May 1, 1753 - is taken as starting point botanical nomenclature.

- 10th edition Systema naturae(“System of Nature”). The publication date of this edition - January 1, 1758 - is taken as the starting point of zoological nomenclature.

- Amoenitates academicae(“Academic leisure”, 1751-1790). A ten-volume collection of dissertations written by Linnaeus for his students and partly by the students themselves. Published in Leiden, Stockholm and Erlangen: seven volumes were published during his lifetime (from 1749 to 1769), three more volumes - after his death (from 1785 to 1790). The topics of these works relate to various fields of natural science - botany, zoology, chemistry, anthropology, medicine, mineralogy, etc.

In 1758, Linnaeus acquired the estate (farm) of Hammarby, approximately ten kilometers southeast of Uppsala; the country house in Hammarby became his summer estate (the estate has been preserved and is now part of the botanical garden "Linnaean Hammarby" owned by Uppsala University).

In 1774, Linnaeus suffered his first stroke (cerebral hemorrhage), as a result of which he was partially paralyzed. In the winter of 1776-1777, a second blow occurred: he lost his memory, tried to leave home, wrote, confusing Latin and Greek letters. On December 30, 1777, Linnaeus became significantly worse, and on January 10, 1778, he died at his home in Uppsala.

As one of the prominent citizens of Uppsala, Linnaeus was buried in Uppsala Cathedral.

Apostles of Linnaeus

The apostles of Linnaeus were his students who participated in botanical and zoological expeditions in various parts of the world, starting in the late 1740s. The plans for some of them were developed by Linnaeus himself or with his participation. From their travels, most of the “apostles” brought or sent plant seeds, herbarium and zoological specimens to their teacher. The expeditions were associated with great dangers: of the 17 disciples who are usually classified as “apostles,” seven died during the travels. This fate also befell Christopher Thernström (1703-1746), the very first “apostle of Linnaeus”; after Ternström's widow accused Linnaeus of the fact that it was his fault that her children would grow up orphans, he began to send on expeditions only those of his students who were unmarried.

Contribution to science

Linnaeus laid the foundations of modern binomial (binary) nomenclature, introducing the so-called taxonomy into practice nomina trivialia, which later began to be used as species epithets in the binomial names of living organisms. The method introduced by Linnaeus of forming a scientific name for each species is still used today (the previously used long names consisting of large quantity words, gave a description of the species, but were not strictly formalized). The use of a two-word Latin name - the genus name, then the specific name - allowed nomenclature to be separated from taxonomy.

Carl Linnaeus is the author of the most successful artificial classification of plants and animals, which became the basis for the scientific classification of living organisms. He shared natural world into three “kingdoms”: mineral, plant and animal, using four levels (“ranks”): classes, orders, genera and species.

Described about one and a half thousand new plant species ( total number the plant species described by him - more than ten thousand) and a large number of animal species.

Since the 18th century, along with the development of botany, phenology, the science of seasonal natural phenomena, the timing of their occurrence and the reasons that determine these timings, began to actively develop. In Sweden, it was Linnaeus who first began to conduct scientific phenological observations (since 1748); later he organized a network of observers consisting of 18 stations, which existed from 1750 to 1752. One of the first in the world scientific works on phenology was the work of Linnaeus in 1756 Calendaria Florae; it describes the development of nature for the most part using the example of the plant kingdom.

Humanity owes the current Celsius scale partly to Linnaeus. Initially, the scale of the thermometer, invented by Linnaeus' colleague at Uppsala University, Professor Anders Celsius (1701-1744), had zero at the boiling point of water and 100 degrees at the freezing point. Linnaeus, who used thermometers to measure conditions in greenhouses and greenhouses, found this inconvenient and in 1745, after the death of Celsius, “turned over” the scale.

Linnaeus Collection

Carl Linnaeus left a huge collection, which included two herbariums, a collection of shells, a collection of insects and a collection of minerals, as well a big library. “This is the greatest collection the world has ever seen,” he wrote to his wife in a letter that he willed to be made public after his death.

After long family disagreements and contrary to the instructions of Carl Linnaeus, the entire collection went to his son, Carl Linnaeus the Younger (1741-1783), who moved it from the Hammarby Museum to his home in Uppsala and to highest degree worked diligently to preserve the items included in it (the herbarium and the collection of insects had already suffered from pests and dampness by that time). The English naturalist Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820) offered to sell his collection, but he refused.

But soon after the sudden death of Carl Linnaeus the Younger from a stroke at the end of 1783, his mother (the widow of Carl Linnaeus) wrote to Banks that she was ready to sell him the collection. He did not buy it himself, but convinced the young English naturalist James Edward Smith (1759-1828) to do so. Potential buyers were also Carl Linnaeus' student Baron Claes Alströmer (1736-1794), Russian Empress Catherine the Great, English botanist John Sibthorpe (1758-1796) and others, but Smith turned out to be more prompt: having quickly approved the inventory sent to him, he approved the deal. Scientists and students at Uppsala University demanded that the authorities do everything to leave Linnaeus’ legacy in their homeland, but King Gustav III of Sweden was in Italy at the time, and government officials responded that they could not resolve this issue without his intervention...

In September 1784, the collection left Stockholm on an English brig and was soon safely delivered to England. The legend according to which the Swedes sent their warship to intercept an English brig carrying out the Linnaeus collection has no scientific basis, although it is depicted in an engraving from R. Thornton’s book “A New Illustration of the Linnaeus System”.

The collection received by Smith included 19 thousand herbarium sheets, more than three thousand insect specimens, more than one and a half thousand shells, over seven hundred coral specimens, two and a half thousand mineral specimens; the library consisted of two and a half thousand books, over three thousand letters, as well as manuscripts of Carl Linnaeus, his son and other scientists.

Linneanism

During his lifetime, Linnaeus gained worldwide fame; adherence to his teaching, conventionally called Linneanism, became widespread at the end of the 18th century. And although Linnaeus’s concentration in the study of phenomena on the collection of material and its further classification looks from the point of view today excessive, and the approach itself seems very one-sided, for its time the activities of Linnaeus and his followers became very important. The spirit of systematization that permeated this activity helped biology in a fairly short time to become a full-fledged science and, in a sense, to catch up with physics, which was actively developing during the 18th century as a result of the scientific revolution.

One of the forms of Linneanism was the creation of “Linnaean societies” - scientific associations of naturalists who built their activities on the basis of Linnaeus’ ideas. During his lifetime, in 1874, the Linnean Society of New South Wales arose in Australia, which still exists today.

Soon after the London Society, a similar society appeared in Paris - the “Parisian Linnean Society”. Its heyday came in the first years after the French Revolution. Later, similar “Linnaean societies” appeared in Australia, Belgium, Spain, Canada, USA, Sweden and other countries. Many of these societies still exist today.

Honors

Even during his lifetime, Linnaeus was given metaphorical names that emphasized his unique significance for world science. They called him Princeps botanicorum(there are several translations into Russian - “First among Botanists”, “Prince of Botanists”, “Prince of Botanists”), “Northern Pliny” (in this name Linnaeus is compared with

Carl Linnaeus (Swedish: Carl Linnaeus, 1707-1778) - an outstanding Swedish scientist, naturalist and physician, professor at Uppsala University. He laid down the principles of classification of nature, dividing it into three kingdoms. The merits of the great scientist were those left behind by him detailed descriptions plants and one of the most successful artificial classifications of plants and animals. He introduced the concept of taxa into science and proposed a method of binary nomenclature, and also built a system of the organic world based on the hierarchical principle.

Childhood and youth

Carl Linnaeus was born on May 23, 1707 in the Swedish city of Rossult in the family of a rural pastor, Nicholas Linneus. He was such a keen florist that he changed his previous surname Ingemarson to the Latinized version Linnaeus from the name of a huge linden tree (Lind in Swedish) that grew not far from his house. Despite great desire parents wanted their first-born to be a priest; from a young age he was attracted to natural sciences, and especially botany.

When the son was two years old, the family moved to the neighboring town of Stenbrohult, but the future scientist studied in the town of Växjo - first at the local grammar school, and then at the gymnasium. The main subjects - ancient languages and theology - were not easy for Charles. But the young man was passionate about mathematics and botany. For the sake of the latter, he often skipped classes in order to study plants in natural conditions. He also mastered Latin with great difficulty, and then only for the opportunity to read Pliny’s “Natural History” in the original. On the advice of Dr. Rothman, who taught logic and medicine to Karl, the parents decided to send their son to study as a doctor.

Studying at the University

In 1727, Linnaeus successfully passed the exams at Lund University. Here, he was most impressed by the lectures of Professor K. Stobeus, who helped to replenish and systematize Karl’s knowledge. During his first year of study, he meticulously studied the flora of the area around Lund and created a catalog of rare plants. However, Linnaeus did not study in Lund for long: on Rothman’s advice, he transferred to Uppsala University, which had a more medical focus. However, the level of teaching in both educational institutions was below the capabilities of a student of Linnaeus, so most of the time he was engaged in self-education. In 1730, he began teaching in the botanical garden as a demonstrator and had great success among his students.

However, there were still benefits from staying in Uppsala. Within the walls of the university, Linnaeus met Professor O. Celsius, who sometimes helped a poor student with money, and Professor W. Rudbeck Jr., on whose advice he went on a trip to Lapland. In addition, fate brought him together with student P. Artedi, with whom the natural history classification would be revised.

In 1732, Karl visited Lapland to study in detail the three kingdoms of nature - plants, animals and minerals. He also collected a large amount of ethnographic material, including about the life of the aborigines. Following the trip, Linnaeus wrote a short review work, which in 1737 was published in an expanded version under the title “Flora Lapponica”. My research activities the aspiring scientist continued in 1734, when, at the invitation of the local governor, he went to Delecarlia. After that, he moved to Falun, where he was engaged in assaying and studying minerals.

Dutch period

In 1735, Linnaeus went to the shores of the North Sea as a candidate for a doctorate in medicine. This trip took place, among other things, at the insistence of his future father-in-law. Having defended his dissertation at the University of Harderwijk, Karl enthusiastically studied the natural science classrooms of Amsterdam, and then went to Leiden, where one of his fundamental works “Systema naturae” was published. In it, the author presented the distribution of plants into 24 classes, laying the basis for classification according to the number, size, location of stamens and pistils. Later, the work would be constantly updated, and 12 editions would be published during Linnaeus's lifetime.

The created system turned out to be very accessible even to non-professionals, allowing them to easily identify plants and animals. Its author was aware of his special purpose, calling himself the chosen one of the Creator, called upon to interpret his plans. In addition, in Holland he writes “Bibliotheca Botanica”, in which he systematizes literature on botany, “Genera plantraum” with a description of plant genera, “Classes plantraum” - a comparison various classifications plants with the author’s own system and a number of other works.

Homecoming

Returning to Sweden, Linnaeus began practicing medicine in Stockholm and quickly entered the royal court. The reason was the healing of several ladies-in-waiting with a decoction of yarrow. He widely used medicinal plants in his activities, in particular, he used strawberries to treat gout. The scientist made a lot of efforts to create the Royal Academy of Sciences (1739), became its first president and was awarded the title of “royal botanist”.

In 1742, Linnaeus fulfilled his old dream and became a professor of botany at his alma mater. Under him, the Department of Botany at Uppsala University (Karl headed it for more than 30 years) acquired enormous respect and authority. The Botanical Garden played an important role in his studies, where several thousand plants grew, collected literally from all over the world. "IN natural sciences principles must be confirmed by observations"- said Linnaeus. At this time, real success and fame came to the scientist: Karl was admired by many outstanding contemporaries, including Rousseau. During the Age of Enlightenment, scientists like Linnaeus were all the rage.

Having settled on his estate Gammarba near Uppsala, Karl moved away from medical practice and plunged headlong into science. He managed to describe all the medicinal plants known at that time and study the effects of drugs produced from them on humans. In 1753, he published his main work, “The System of Plants,” on which he worked for a quarter of a century.

Linnaeus's scientific contributions

Linnaeus managed to correct the existing shortcomings of botany and zoology, whose mission had previously been reduced to a simple description of objects. The scientist forced everyone to take a fresh look at the goals of these sciences by classifying objects and developing a system for recognizing them. Linnaeus's main merit is related to the field of methodology - he did not discover new laws of nature, but he was able to organize the already accumulated knowledge. The scientist proposed a method of binary nomenclature, according to which names were assigned to animals and plants. He divided nature into three kingdoms and used four ranks to systematize it - classes, orders, species and genera.

Linnaeus classified all plants into 24 classes in accordance with the characteristics of their structure and identified their genus and species. In the second edition of the book "Species of Plants" he presented a description of 1260 genera and 7540 species of plants. The scientist was convinced that plants have sex and based the classification on the structural features of stamens and pistils he identified. When using the names of plants and animals, it was necessary to use the generic and species names. This approach put an end to the chaos in the classification of flora and fauna, and over time became important tool determining the kinship of individual species. To make the new nomenclature easy to use and not cause ambiguity, the author described each species in detail, introducing precise terminological language into science, which he outlined in detail in the work “Fundamental Botany.”

At the end of his life, Linnaeus tried to apply his principle of systematization to all of nature, including rocks and minerals. He was the first to classify humans and monkeys as members of the general group of primates. At the same time, the Swedish scientist was never a supporter of the evolutionary direction and believed that the first organisms were created in some kind of paradise. He sharply criticized proponents of the idea of species variability, calling it a departure from biblical traditions. “Nature does not make a leap,” the scientist repeated more than once.

In 1761, after four years of waiting, Linnaeus received a title of nobility. This allowed him to slightly modify his surname in the French manner (von Linne) and create his own coat of arms, the central elements of which were three symbols of the kingdoms of nature. Linnaeus came up with the idea of making a thermometer, for the creation of which he used the Celsius scale. For his numerous merits, in 1762 the scientist was admitted to the ranks of the Paris Academy of Sciences.

IN last years Throughout his life, Karl was seriously ill and suffered several strokes. He died in his own home in Uppsala on January 10, 1778 and was buried in the local cathedral.

The scientist's scientific heritage was presented in the form of a huge collection, including a collection of shells, minerals and insects, two herbariums and a huge library. Despite the family disputes that arose, it went to Linnaeus’s eldest son and his full namesake, who continued his father’s work and did everything to preserve this collection. After his premature death, she came to the English naturalist John Smith, who founded the Linnean Society of London in the British capital.

Personal life

The scientist was married to Sarah Lisa Morena, whom he met in 1734, the daughter of the city doctor of Falun. The romance proceeded very stormily, and two weeks later Karl decided to propose to her. In the spring of 1735, they rather modestly became engaged, after which Karl went to Holland to defend his dissertation. Due to various circumstances, their wedding took place only 4 years later in the family farm of the bride’s family. Linnaeus became the father of many children: he had two sons and five daughters, two of whom died in infancy. In honor of his wife and father-in-law, the scientist named Moraea a genus of perennial plants from the Iris family, growing in South Africa.

Carl Linnaeus was born on May 23, 1707 in the village of Roshult in Sweden in the family of a priest. Two years later he and his family moved to Stenbrohult. Interest in plants in the biography of Carl Linnaeus appeared already in childhood. Elementary education received at a school in the city of Växjö, and after graduating from school he entered the gymnasium. Linnaeus's parents wanted the boy to continue the family business and become a pastor. But Karl was of little interest in theology. He devoted a lot of time to studying plants.

Thanks to the insistence of school teacher Johan Rothman, Karl's parents allowed him to study medical sciences. Then the university stage began. Karl began studying at the University of Lund. And in order to become more familiar with medicine, a year later he moved to Uppsald University. In addition, he continued to educate himself. Together with a student at the same university, Peter Artedi, Linnaeus began revising and criticizing the principles of natural science.

In 1729, an acquaintance took place with W. Celsius, who played important role in the development of Linnaeus as a botanist. Then Karl moved to the house of Professor Celsius and began to get acquainted with his huge library. Basic Ideas Linnaeus's classification of plants was outlined in his first work, “Introduction to the Sexual Life of Plants.”

A year later, Linnaeus had already begun teaching and lecturing at the botanical garden of Uppsald University.

He spent the period from May to October 1732 in Lapland. After fruitful work during the trip, his book “A Brief Flora of Lapland” was published. It was in this work that the reproductive system in flora. The following year, Linnaeus became interested in mineralogy, even publishing a textbook. Then in 1734, in order to study plants, he went to the province of Dalarna.

He received his doctorate in medicine in June 1735 from the University of Harderwijk. Linnaeus's next work, The System of Nature, marked new stage in Linnaeus's career and life in general. Thanks to new connections and friends, he received the position of caretaker of one of the largest botanical gardens in Holland, which collected plants from all over the world. So Karl continued to classify plants. And after the death of his friend Peter, Artedi published his work and later used his ideas for classifying fish. While living in Holland, Linnaeus's works were published: “Fundamenta Botanica”, “Musa Cliffordiana”, “Hortus Clifortianus”, “Critica botanica”, “Genera plantarum” and others.

The scientist returned to his homeland in 1773. There in Stockholm he began practicing medicine, using his knowledge of plants to treat people. He also taught, was chairman of the Royal Academy of Sciences, and a professor at Uppsala University (he retained the position until his death).

Then Carly Linnaeus went on an expedition to the islands in his biography Baltic Sea, visited western and southern Sweden. And in 1750 he became rector of the university where he had previously taught. In 1761 he received the status of a nobleman. And on January 10, 1778, Linnaeus died.

Biography score

New feature! The average rating this biography received. Show rating

Carl Linnaeus

Linne (Linne, Linnaeus) Karl (23.5.1707, Rosshuld, - 10.1.1778, Uppsala), Swedish naturalist, member of the Paris Academy of Sciences (1762). He gained worldwide fame thanks to the system of flora and fauna he created. Born into the family of a village pastor. He studied natural and medical sciences at Lund (1727) and Uppsala (since 1728) universities. In 1732 he made a trip to Lapland, the result of which was the work “Flora of Lapland” (1732, complete publication in 1737). In 1735 he moved to Hartekamp (Holland), where he was in charge of the botanical garden; defended his doctoral dissertation “New hypothesis of intermittent fevers.” In the same year he published the book “The System of Nature” (published during his lifetime in 12 editions). From 1738 he practiced medicine in Stockholm; in 1739 he headed the naval hospital and won the right to autopsy corpses to determine the cause of death. He participated in the creation of the Swedish Academy of Sciences and became its first president (1739). From 1741 he was the head of the department at Uppsala University, where he taught medicine and natural sciences.

The system of flora and fauna created by Linnaeus completed great work botanists and zoologists of the 1st half of the 18th century. One of Linnaeus’s main merits is that in his “System of Nature” he applied and introduced the so-called binary nomenclature, according to which each species is designated by two Latin names - generic and specific. Linnaeus defined the concept of “species” using both morphological (similarity within the offspring of one family) and physiological (the presence of fertile offspring) criteria, and established a clear subordination between systematic categories: class, order, genus, species, variation.

Linnaeus based the classification of plants on the number, size and location of the stamens and pistils of a flower, as well as the sign of a plant being mono-, bi- or multi-homogenous, since he believed that the reproductive organs are the most essential and permanent parts of the body in plants. Based on this principle, he divided all plants into 24 classes. Thanks to the simplicity of the nomenclature he used, descriptive work was greatly facilitated, and species received clear characteristics and names. Linnaeus himself discovered and described about 1,500 plant species.

Linnaeus divided all animals into 6 classes:

- Mammals

- Birds

- Amphibians

- Fish

- Worms

- Insects

The class of amphibians included amphibians and reptiles; he included all forms of invertebrates known in his time, except insects, into the class of worms. One of the advantages of this classification is that man was included in the system of the animal kingdom and assigned to the class of mammals, to the order of primates. The classifications of plants and animals proposed by Linnaeus are artificial from a modern point of view, since they are based on a small number of arbitrarily taken characters and do not reflect the actual relationship between in different forms. So, based on only one common feature- beak structure - Linnaeus tried to build a “natural” system based on a combination of many characteristics, but did not achieve his goal.

Linnaeus was opposed to the idea of true development of the organic world; he believed that the number of species remains constant, they did not change over the time of their “creation,” and therefore the task of systematics is to reveal the order in nature established by the “creator.” However, the vast experience accumulated by Linnaeus, his acquaintance with plants from various localities could not help but shake his metaphysical ideas. In his last works, Linnaeus very cautiously suggested that all species of the same genus initially constituted one species, and allowed the possibility of the emergence of new species formed as a result of crossings between pre-existing species.

Linnaeus also classified soils and minerals, human races, illness (by symptoms); discovered the poisonous and healing properties of many plants. Linnaeus is the author of a number of works, mainly on botany and zoology, as well as in the field of theoretical and practical medicine(“Medicinal substances”, “Kinds of diseases”, “Key to Medicine”).

Linnaeus's libraries, manuscripts and collections were sold by his widow to the English botanist Smith, who founded (1788) the Linnean Society in London, which still exists today as one of the largest scientific centers.

- In contact with 0

- Google+ 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0