The West Siberian Plain is one of the largest accumulative low-lying plains in the world. It stretches from the shores of the Kara Sea to the steppes of Kazakhstan and from the Urals in the west to the Central Siberian Plateau in the east. The plain has the shape of a trapezoid tapering to the north: the distance from its southern border to the northern reaches almost 2500 km, width - from 800 to 1900 km, and the area is only slightly less than 3 million sq. km 2 .

There are no other such vast plains in the Soviet Union, with such a weakly rugged relief and such small fluctuations in relative heights. The comparative uniformity of the relief determines the distinct zonality of the landscapes of Western Siberia - from tundra in the north to steppe in the south. Due to the poor drainage of the territory within its boundaries, hydromorphic complexes play a very prominent role: swamps and swampy forests occupy here a total of about 128 million hectares. ha, and in the steppe and forest-steppe zones there are many solonetzes, solods and solonchaks.

The geographical position of the West Siberian Plain determines the transitional nature of its climate between the temperate continental climate of the Russian Plain and the sharply continental climate of Central Siberia. Therefore, the landscapes of the country are distinguished by a number of peculiar features: the natural zones here are somewhat shifted to the north compared to the Russian Plain, the zone of broad-leaved forests is absent, and landscape differences within the zones are less noticeable than on the Russian Plain.

The West Siberian Plain is the most inhabited and developed (especially in the south) part of Siberia. Within its boundaries are the Tyumen, Kurgan, Omsk, Novosibirsk, Tomsk and North Kazakhstan regions, a significant part of the Altai Territory, Kustanai, Kokchetav and Pavlodar regions, as well as some eastern regions of Sverdlovsk and Chelyabinsk regions And western regions Krasnoyarsk Territory.

The acquaintance of Russians with Western Siberia took place for the first time, probably, as early as the 11th century, when the Novgorodians visited the lower reaches of the Ob. Ermak's campaign (1581-1584) opens a brilliant period of the Great Russian geographical discoveries in Siberia and the development of its territory.

However, the scientific study of the nature of the country began only in the 18th century, when detachments of the Great Northern expedition and then academic expeditions were sent here. In the 19th century Russian scientists and engineers are studying the conditions of navigation on the Ob, the Yenisei and the Kara Sea, the geological and geographical features of the route of the Siberian railway, salt deposits in the steppe zone. A significant contribution to the knowledge of the West Siberian taiga and steppes was made by studies of soil-botanical expeditions of the Migration Administration, undertaken in 1908-1914. in order to study the conditions for the agricultural development of plots allocated for the resettlement of peasants from European Russia.

The study of the nature and natural resources of Western Siberia acquired a completely different scope after the Great October revolution. In the research that was necessary for the development of the productive forces, no longer individual specialists or small detachments took part, but hundreds of large complex expeditions and many scientific institutes created in various cities of Western Siberia. Detailed and versatile studies were carried out here by the USSR Academy of Sciences (Kulunda, Baraba, Gydan and other expeditions) and its Siberian branch, the West Siberian Geological Administration, geological institutes, expeditions of the Ministry of Agriculture, Hydroproject and other organizations.

As a result of these studies, ideas about the country's relief have changed significantly, detailed soil maps of many regions of Western Siberia have been compiled, and measures have been developed for the rational use of saline soils and the famous West Siberian chernozems. big practical value had forest typological studies of Siberian geobotanists, the study of peat bogs and tundra pastures. But especially significant results were brought by the work of geologists. Deep drilling and special geophysical studies have shown that the bowels of many regions of Western Siberia contain the richest deposits of natural gas, large reserves of iron ore, brown coal and many other minerals, which already serve as a solid base for the development of industry in Western Siberia.

Geological structure and history of the development of the territory

Taz Peninsula and the Middle Ob in the section Nature of the world.

Many features of the nature of Western Siberia are due to the nature of its geological structure and history of development. The entire territory of the country is located within the West Siberian epihercynian plate, the foundation of which is composed of dislocated and metamorphosed Paleozoic deposits, similar in nature to those of the Urals, and in the south of the Kazakh upland. The formation of the main folded structures of the basement of Western Siberia, which have a predominantly meridional direction, refers to the era of the Hercynian orogeny.

The tectonic structure of the West Siberian plate is rather heterogeneous. However, even its large structural elements appear in the modern relief less distinctly than the tectonic structures of the Russian Platform. This is explained by the fact that the topography of the surface of the Paleozoic rocks, subsided to a great depth, is leveled here by the cover of the Meso-Cenozoic deposits, the thickness of which exceeds 1000 m, and in separate depressions and syneclises of the Paleozoic basement - 3000-6000 m.

The Mesozoic formations of Western Siberia are represented by marine and continental sandy-argillaceous deposits. Their total capacity in some areas reaches 2500-4000 m. The alternation of marine and continental facies indicates the tectonic mobility of the territory and repeated changes in the conditions and regime of sedimentation on the West Siberian Plate that sank at the beginning of the Mesozoic.

Paleogene deposits are predominantly marine and consist of gray clays, mudstones, glauconite sandstones, opokas, and diatomites. They accumulated at the bottom of the Paleogene Sea, which, through the depression of the Turgai Strait, connected the Arctic basin with the seas that were then located on the territory of Central Asia. This sea left Western Siberia in the middle of the Oligocene, and therefore the Upper Paleogene deposits are already represented here by sandy-clayey continental facies.

Significant changes in the conditions of accumulation of sedimentary deposits occurred in the Neogene. The suites of Neogene rocks, which come to the surface mainly in the southern half of the plain, consist exclusively of continental lacustrine-river deposits. They formed in the conditions of a poorly dissected plain, first covered with rich subtropical vegetation, and later with broad-leaved deciduous forests from representatives of the Turgai flora (beech, walnut, hornbeam, lapina, etc.). In some places there were areas of savannas, where giraffes, mastodons, hipparions, and camels lived at that time.

Especially big influence the formation of the landscapes of Western Siberia was influenced by the events of the Quaternary period. During this time, the territory of the country experienced repeated subsidence and was still an area of predominantly accumulation of loose alluvial, lacustrine, and in the north - marine and glacial deposits. The thickness of the Quaternary cover in the northern and central regions reaches 200-250 m. However, in the south it noticeably decreases (in some places up to 5-10 m), and in the modern relief, the effects of differentiated neotectonic movements are clearly expressed, as a result of which swell-like uplifts arose, often coinciding with the positive structures of the Mesozoic cover of sedimentary deposits.

Lower Quaternary deposits are represented in the north of the plain by alluvial sands filling buried valleys. The sole of alluvium is located in them sometimes at 200-210 m below the current level of the Kara Sea. Above them in the north, pre-glacial clays and loams with fossil remains of the tundra flora usually occur, which indicates a noticeable cooling of Western Siberia that had already begun at that time. However, dark coniferous forests with an admixture of birch and alder prevailed in the southern regions of the country.

The Middle Quaternary time in the northern half of the plain was an epoch of marine transgressions and repeated glaciations. The most significant of them was Samarovskoye, the deposits of which compose the interfluves of the territory lying between 58-60 ° and 63-64 ° N. sh. According to currently prevailing views, the cover of the Samara glacier, even in the extreme northern regions of the lowland, was not continuous. The composition of boulders shows that its sources of food were glaciers descending from the Urals to the Ob valley, and in the east - glaciers of the Taimyr mountain ranges and the Central Siberian Plateau. However, even during the period of maximum development of glaciation in the West Siberian Plain, the Ural and Siberian ice sheets did not merge with each other, and the rivers of the southern regions, although they met a barrier formed by ice, found their way north in the gap between them.

Along with typical glacial rocks, the composition of the sediments of the Samarovo stratum also includes marine and glacial-marine clays and loams formed at the bottom of the sea advancing from the north. Therefore, the typical moraine relief forms are less distinct here than on the Russian Plain. On the lacustrine and fluvioglacial plains adjoining the southern edge of the glaciers, then forest-tundra landscapes prevailed, and in the extreme south of the country loess-like loams were formed, in which pollen of steppe plants (wormwood, kermek) is found. Marine transgression continued in the post-Samarovo time, the deposits of which are represented in the north of Western Siberia by Messov sands and clays of the Sanchugov Formation. In the northeastern part of the plain, moraines and glacial-marine loams of the younger Taz glaciation are common. The interglacial epoch, which began after the retreat of the ice sheet, was marked in the north by the spread of the Kazantsevo marine transgression, whose sediments in the lower reaches of the Yenisei and Ob contained the remains of a more heat-loving marine fauna than currently living in the Kara Sea.

The last, Zyryansk, glaciation was preceded by a regression of the boreal sea, caused by uplifts in the northern regions of the West Siberian Plain, the Urals, and the Central Siberian Plateau; the amplitude of these uplifts was only a few tens of meters. During the maximum stage of development of the Zyryansk glaciation, glaciers descended into the regions of the Yenisei Plain and the eastern foot of the Urals to approximately 66 ° N. sh., where a number of stadial terminal moraines were left. In the south of Western Siberia, sandy-argillaceous Quaternary sediments were being blown over at that time, eolian landforms were forming, and loess-like loams were accumulating.

Some researchers of the northern regions of the country draw a more complex picture of the events of the Quaternary glaciation in Western Siberia. Thus, according to the geologist V.N. Saks and geomorphologist G.I. Lazukov, glaciation began here as early as the Lower Quaternary and consisted of four independent epochs: Yarskaya, Samarovo, Taz and Zyryanskaya. Geologists S. A. Yakovlev and V. A. Zubakov even count six glaciations, referring the beginning of the most ancient of them to the Pliocene.

On the other hand, there are supporters of a one-time glaciation of Western Siberia. Geographer A. I. Popov, for example, considers the deposits of the glaciation era of the northern half of the country as a single water-glacial complex consisting of marine and glacial-marine clays, loams and sands containing inclusions of boulder material. In his opinion, there were no extensive ice sheets on the territory of Western Siberia, since typical moraines are found only in the extreme western (at the foot of the Urals) and eastern (near the ledge of the Central Siberian Plateau) regions. The middle part of the northern half of the plain during the epoch of glaciation was covered by the waters of marine transgression; the boulders enclosed in its deposits are brought here by icebergs that have come off the edge of the glaciers that descended from the Central Siberian Plateau. Only one Quaternary glaciation of Western Siberia is recognized by the geologist V. I. Gromov.

At the end of the Zyryansk glaciation, the northern coastal regions of the West Siberian Plain again sank. The subsided areas were flooded by the waters of the Kara Sea and covered with marine sediments that make up post-glacial marine terraces, the highest of which rises 50-60 m above the modern level of the Kara Sea. Then, after the regression of the sea, a new incision of rivers began in the southern half of the plain. Due to the small slopes of the channel in most of the river valleys of Western Siberia, lateral erosion prevailed, the deepening of the valleys proceeded slowly, therefore they usually have a considerable width, but a small depth. In poorly drained interfluve spaces, the reworking of the ice age relief continued: in the north, it consisted in leveling the surface under the influence of solifluction processes; in the southern, non-glacial provinces, where more atmospheric precipitation fell, the processes of deluvial washout played a particularly prominent role in the transformation of the relief.

Paleobotanical materials suggest that after the glaciation there was a period with somewhat drier and warm climate, than now. This is confirmed, in particular, by the finds of stumps and tree trunks in the deposits of the tundra regions of Yamal and the Gydan Peninsula at 300-400 km to the north of the modern border of woody vegetation and the wide development of the tundra zone of relict large-hilly peatlands in the south.

Currently, there is a slow shift of borders on the territory of the West Siberian Plain. geographical areas to the south. Forests in many places advance on the forest-steppe, forest-steppe elements penetrate into the steppe zone, and the tundra is slowly replacing woody vegetation near the northern limit of sparse forests. True, in the south of the country, man intervenes in the natural course of this process: by cutting down forests, he not only stops their natural advance on the steppe, but also contributes to the displacement of the southern border of forests to the north.

Relief

See photos of the nature of the West Siberian Plain: the Taz Peninsula and the Middle Ob in the Nature of the World section.

Scheme of the main orographic elements of the West Siberian Plain

Differentiated subsidence of the West Siberian Plate in the Mesozoic and Cenozoic determined the predominance of accumulation processes of loose deposits within it, the thick cover of which levels the unevenness of the surface of the Hercynian basement. Therefore, the modern West Siberian Plain is characterized by a generally flat surface. However, it cannot be considered as a monotonous lowland, as it was considered until recently. In general, the territory of Western Siberia has a concave shape. Its lowest parts (50-100 m) are located mainly in the central ( Kondinskaya and Sredneobskaya lowlands) and northern ( Nizhneobskaya, Nadymskaya and Purskaya lowlands) parts of the country. Along the western, southern and eastern outskirts stretch low (up to 200-250 m) hills: Severo-Sosvinskaya, Turin, Ishimskaya, Priobskoe and Chulym-Yenisei plateau, Ketsko-Tymskaya, Verkhnetazovskaya, Lower Yenisei. A distinct strip of hills form in the inner part of the plain Siberian Ridges(average height - 140-150 m), stretching from the west from the Ob to the east to the Yenisei, and parallel to them Vasyuganskaya plain.

Some orographic elements of the West Siberian Plain correspond to geological structures: gently sloping anticlinal uplifts correspond, for example, to the Verkhnetazovsky and lulimvor, but Barabinskaya and Kondinskaya the lowlands are confined to the syneclises of the slab basement. However, discordant (inversion) morphostructures are also not uncommon in Western Siberia. These include, for example, the Vasyugan Plain, which formed on the site of a gently sloping syneclise, and the Chulym-Yenisei Plateau, located in the basement trough zone.

The West Siberian Plain is usually divided into four large geomorphological regions: 1) marine accumulative plains in the north; 2) glacial and water-glacial plains; 3) near-glacial, mainly lacustrine-alluvial, plains; 4) southern non-glacial plains (Voskresensky, 1962).

The differences in the relief of these areas are explained by the history of their formation in the Quaternary, the nature and intensity of the latest tectonic movements, and zonal differences in modern exogenous processes. In the tundra zone, relief forms are especially widely represented, the formation of which is associated with a harsh climate and the widespread distribution of permafrost. Thermokarst basins, bulgunnyakhs, spotted and polygonal tundras are quite common, and solifluction processes are developed. The southern steppe provinces are characterized by numerous closed basins of suffusion origin, occupied by salt marshes and lakes; the network of river valleys here is not dense, and erosional landforms in the interfluves are rare.

The main elements of the relief of the West Siberian Plain are wide flat interfluves and river valleys. Due to the fact that the interfluve spaces account for a large part of the country's area, they determine the general appearance of the relief of the plain. In many places, the slopes of their surface are insignificant, the runoff of precipitation, especially in the forest-bog zone, is very difficult, and the interfluves are heavily swamped. Large areas are occupied by swamps to the north of the line of the Siberian railway, on the interfluve of the Ob and Irtysh, in the Vasyugan region and the Baraba forest-steppe. However, in some places the relief of the interfluves takes on the character of a wavy or hilly plain. Such areas are especially typical of certain northern provinces of the plain, which were subjected to Quaternary glaciations, which left here a heap of stadial and bottom moraines. In the south - in Baraba, on the Ishim and Kulunda plains - the surface is often complicated by numerous low ridges stretching from the northeast to the southwest.

Another important element of the country's relief is the river valleys. All of them were formed in conditions of small slopes of the surface, slow and calm flow of rivers. Due to differences in the intensity and nature of erosion, the appearance of the river valleys of Western Siberia is very diverse. There are also well-developed deep (up to 50-80 m) valleys of large rivers - the Ob, Irtysh and Yenisei - with a steep right bank and a system of low terraces on the left bank. In places, their width is several tens of kilometers, and the Ob valley in the lower reaches even 100-120 km. The valleys of most small rivers are often only deep ditches with poorly defined slopes; during spring floods, water completely fills them and floods even neighboring valley areas.

Climate

See photos of the nature of the West Siberian Plain: the Taz Peninsula and the Middle Ob in the Nature of the World section.

Western Siberia is a country with a fairly severe continental climate. Its large extent from north to south causes a distinct climate zoning and significant differences climatic conditions northern and southern parts of Western Siberia, associated with a change in the amount of solar radiation and the nature of the circulation of air masses, especially western transport flows. The southern provinces of the country, located inland, at a great distance from the oceans, are also characterized by a more continental climate.

During the cold period, two baric systems interact within the country: an area of relatively high atmospheric pressure, located above the southern part of the plain, an area of low pressure, which in the first half of winter extends in the form of a hollow of the Icelandic baric minimum over the Kara Sea and northern peninsulas. In winter, masses of continental air of temperate latitudes predominate, which come from Eastern Siberia or are formed on the spot as a result of air cooling over the territory of the plain.

Cyclones often pass in the border zone of areas of high and low pressure. Especially often they are repeated in the first half of winter. Therefore, the weather in the maritime provinces is very unstable; on the coast of Yamal and the Gydan Peninsula, strong winds are guaranteed, the speed of which reaches 35-40 m/s. The temperature here is even somewhat higher than in the neighboring forest-tundra provinces located between 66 and 69°N. sh. Further south, however, winter temperatures gradually rise again. In general, winter is characterized by stable low temperatures, there are few thaws here. The minimum temperatures throughout Western Siberia are almost the same. Even near the southern border of the country, in Barnaul, there are frosts down to -50 -52 °, i.e., almost the same as in the far north, although the distance between these points is more than 2000 km. Spring is short, dry and comparatively cold; April, even in the forest-marsh zone, is not yet quite a spring month.

In the warm season, low pressure sets in over the country, and an area of higher pressure forms over the Arctic Ocean. In connection with this summer, weak northerly or northeasterly winds predominate, and the role of western air transport noticeably increases. In May, there is a rapid increase in temperatures, but often, with the intrusions of arctic air masses, there are returns of cold weather and frosts. The warmest month is July, the average temperature of which is from 3.6° on Bely Island to 21-22° in the Pavlodar region. The absolute maximum temperature is from 21° in the north (Bely Island) to 40° in the extreme southern regions (Rubtsovsk). High summer temperatures in the southern half of Western Siberia are explained by the inflow of heated continental air here from the south - from Kazakhstan and Central Asia. Autumn comes late. Even in September, the weather is warm during the day, but November, even in the south, is already a real winter month with frosts up to -20 -35 °.

Most of the precipitation falls in the summer and is brought by air masses coming from the west, from the Atlantic. From May to October, Western Siberia receives up to 70-80% of the annual precipitation. There are especially many of them in July and August, which is explained by intensive activity on the Arctic and polar fronts. The amount of winter precipitation is relatively low and ranges from 5 to 20-30 mm/month. In the south, in some winter months, snow sometimes does not fall at all. Significant fluctuations in the amount of precipitation in different years. Even in the taiga, where these changes are less than in other zones, precipitation, for example, in Tomsk, falls from 339 mm in a dry year up to 769 mm into wet. Especially large differences are observed in the forest-steppe zone, where, with an average long-term precipitation of about 300-350 mm/year in wet years falls up to 550-600 mm/year, and in dry - only 170-180 mm/year.

There are also significant zonal differences in evaporation values, which depend on the amount of precipitation, air temperature, and the evaporative properties of the underlying surface. Moisture evaporates most of all in the rainy-rich southern half of the forest-bog zone (350-400 mm/year). In the north, in the coastal tundra, where the air humidity is relatively high in summer, the amount of evaporation does not exceed 150-200 mm/year. It is approximately the same in the south of the steppe zone (200-250 mm), which is already explained by the low amount of precipitation falling in the steppes. However, evaporation here reaches 650-700 mm, therefore, in some months (especially in May), the amount of evaporating moisture can exceed the amount of precipitation by 2-3 times. In this case, the lack of atmospheric precipitation is compensated by the reserves of moisture in the soil accumulated due to autumn rains and melting snow cover.

The extreme southern regions of Western Siberia are characterized by droughts, which occur mainly in May and June. They are observed on average every three to four years during periods with anticyclonic circulation and increased frequency of arctic air intrusions. The dry air coming from the Arctic, when passing over Western Siberia, is warmed up and enriched with moisture, but its heating is more intense, so the air is increasingly moving away from the state of saturation. In this regard, evaporation increases, which leads to drought. In some cases, the cause of droughts is also the inflow of dry and warm air masses from the south - from Kazakhstan and Central Asia.

In winter, the territory of Western Siberia is covered with snow for a long time, the duration of which in the northern regions reaches 240-270 days, and in the south - 160-170 days. Due to the fact that the period of precipitation in solid form lasts more than six months, and thaws begin no earlier than March, the thickness of the snow cover in the tundra and steppe zones in February is 20-40 cm, in the swampy zone - from 50-60 cm in the west up to 70-100 cm in the eastern Yenisei regions. In treeless - tundra and steppe - provinces, where strong winds and snowstorms occur in winter, snow is distributed very unevenly, as the winds blow it from elevated relief elements into depressions, where powerful snowdrifts form.

The harsh climate of the northern regions of Western Siberia, where the heat entering the soil is not enough to maintain a positive temperature of the rocks, contributes to the freezing of soils and the widespread permafrost. On the Yamal, Tazovsky and Gydansky peninsulas, permafrost is found everywhere. In these areas of its continuous (confluent) distribution, the thickness of the frozen layer is very significant (up to 300-600 m), and its temperatures are low (on the watershed spaces - 4, -9 °, in the valleys -2, -8 °). Further south, within the limits of the northern taiga up to a latitude of about 64°, permafrost occurs already in the form of isolated islands interspersed with taliks. Its power decreases, temperatures rise to? 0.5 -1 °, and the depth of summer thawing also increases, especially in areas composed of mineral rocks.

Water

See photos of the nature of the West Siberian Plain: the Taz Peninsula and the Middle Ob in the Nature of the World section.

Western Siberia is rich in underground and surface waters; in the north, its coast is washed by the waters of the Kara Sea.

The entire territory of the country is located within the large West Siberian artesian basin, in which hydrogeologists distinguish several basins of the second order: Tobolsk, Irtysh, Kulunda-Barnaul, Chulym, Ob, etc. Due to the large thickness of the cover of loose deposits, consisting of alternating permeable ( sands, sandstones) and water-resistant rocks, artesian basins are characterized by a significant number of aquifers associated with suites of various ages - Jurassic, Cretaceous, Paleogene and Quaternary. The groundwater quality of these horizons is very different. In most cases, artesian waters of deep horizons are more mineralized than those lying closer to the surface.

In some aquifers of the Ob and Irtysh artesian basins at a depth of 1000-3000 m there are hot salty waters, most often of chloride calcium-sodium composition. Their temperature is from 40 to 120°C, the daily flow rate of wells reaches 1-1.5 thousand tons per day. m 3, and total stocks - 65,000 km 3; such pressure water can be used for heating cities, greenhouses and greenhouses.

Groundwater in arid steppe and forest-steppe regions of Western Siberia is of great importance for water supply. In many areas of the Kulunda steppe, deep tubular wells were built to extract them. Quaternary groundwater is also used; however, in the southern regions, due to climatic conditions, poor drainage of the surface and slow circulation, they are often highly saline.

The surface of the West Siberian Plain is drained by many thousands of rivers, the total length of which exceeds 250 thousand km. km. These rivers carry out into the Kara Sea annually about 1200 km 3 water - 5 times more than the Volga. The density of the river network is not very high and varies in different places depending on the relief and climatic features: in the Tavda basin it reaches 350 km, and in the Baraba forest-steppe - only 29 km per 1000 km 2. Some southern regions of the country with a total area of more than 445,000 sq. km 2 belong to the territories of closed flow and are distinguished by an abundance of endorheic lakes.

The main sources of food for most rivers are melted snow water and summer-autumn rains. In accordance with the nature of food sources, the runoff is seasonally uneven: approximately 70-80% of its annual amount occurs in spring and summer. Especially a lot of water flows down during the spring flood, when the level major rivers goes up by 7-12 m(in the lower reaches of the Yenisei even up to 15-18 m). For a long time (in the south - five, and in the north - eight months) the West Siberian rivers are ice-bound. Therefore, the winter months account for no more than 10% of the annual runoff.

The rivers of Western Siberia, including the largest ones - the Ob, Irtysh and Yenisei, are characterized by slight slopes and low flow rates. So, for example, the fall of the Ob channel in the section from Novosibirsk to the mouth over 3000 km equals only 90 m, and its flow rate does not exceed 0.5 m/s.

The most important water artery of Western Siberia is the river Ob with its large left tributary the Irtysh. The Ob is one of the greatest rivers in the world. The area of its basin is almost 3 million hectares. km 2 and the length is 3676 km. The Ob basin is located within several geographical zones; in each of them, the nature and density of the river network are different. So, in the south, in the forest-steppe zone, the Ob receives relatively few tributaries, but in the taiga zone their number noticeably increases.

Below the confluence of the Irtysh, the Ob turns into a powerful stream up to 3-4 km. Near the mouth, the width of the river in places reaches 10 km, and depth - up to 40 m. This is one of the most abundant rivers in Siberia; it brings an average of 414 km 3 water.

The Ob is a typical flat river. The slopes of its channel are small: the fall in the upper part is usually 8-10 cm, and below the mouth of the Irtysh does not exceed 2-3 cm for 1 km currents. During spring and summer, the runoff of the Ob near Novosibirsk is 78% per annum; Near the mouth (near Salekhard), the seasonal distribution of runoff is as follows: winter - 8.4%, spring - 14.6, summer - 56 and autumn - 21%.

Six rivers of the Ob basin (Irtysh, Chulym, Ishim, Tobol, Ket and Konda) have a length of more than 1000 km; the length of even some second-order tributaries sometimes exceeds 500 km.

The largest of the tributaries - Irtysh, whose length is 4248 km. Its origins lie outside the Soviet Union, in the mountains of the Mongolian Altai. For a significant part of its turning, the Irtysh crosses the steppes of Northern Kazakhstan and has almost no tributaries right up to Omsk. Only in the lower reaches, already within the taiga, several large rivers flow into it: Ishim, Tobol, etc. The entire length of the Irtysh is navigable, but in the upper reaches in summer, during a period of low water level, navigation is difficult due to numerous rifts.

Along the eastern border of the West Siberian Plain flows Yenisei- the most abundant river Soviet Union. Her length is 4091 km(if we consider the Selenga River as the source, then 5940 km); the basin area is almost 2.6 million sq. km 2. Like the Ob, the Yenisei basin is elongated in the meridional direction. All its major right tributaries flow through the territory of the Central Siberian Plateau. From the flat swampy watersheds of the West Siberian Plain, only the shorter and less watery left tributaries of the Yenisei begin.

The Yenisei originates in the mountains of the Tuva ASSR. In the upper and middle reaches, where the river crosses the spurs of the Sayan Mountains and the Central Siberian Plateau, composed of bedrock, rapids (Kazachinsky, Osinovsky, etc.) occur in its channel. After the confluence of the Lower Tunguska, the current becomes calmer and slower, and sandy islands appear in the channel, breaking the river into channels. The Yenisei flows into the wide Yenisei Bay of the Kara Sea; its width near the mouth, located near the Brekhov Islands, reaches 20 km.

The Yenisei is characterized by large fluctuations in expenditure by season. Its minimum winter consumption near the mouth is about 2500 m 3 /sec, the maximum during the flood period exceeds 132 thousand km. m 3 /sec with an annual average of about 19,800 m 3 /sec. During the year, the river brings to its mouth more than 623 km 3 water. In the lower reaches, the depth of the Yenisei is very significant (in places 50 m). This makes it possible for sea vessels to rise up the river by more than 700 km and reach Igarka.

There are about one million lakes on the West Siberian Plain, the total area of which is more than 100 thousand hectares. km 2. According to the origin of the basins, they are divided into several groups: occupying the primary irregularities of the flat relief; thermokarst; moraine-glacial; lakes of river valleys, which in turn are divided into floodplain and oxbow lakes. Peculiar lakes - "fogs" - are found in the Ural part of the plain. They are located in wide valleys, flood in the spring, sharply reducing their size in the summer, and by autumn, many disappear altogether. In the forest-steppe and steppe regions of Western Siberia there are lakes that fill suffusion or tectonic basins.

Soils, vegetation and wildlife

See photos of the nature of the West Siberian Plain: the Taz Peninsula and the Middle Ob in the Nature of the World section.

The plain relief of Western Siberia contributes to a pronounced zonality in the distribution of soils and vegetation. Within the country there are tundra, forest-tundra, forest-bog, forest-steppe and steppe zones gradually replacing one another. Geographical zonality thus resembles, in general terms, the system of zoning of the Russian Plain. However, the zones of the West Siberian Plain also have a number of local specific features that noticeably distinguish them from similar zones in Eastern Europe. Typical zonal landscapes are located here on dissected and better drained upland and riverine areas. In poorly drained interfluve spaces, the runoff from which is difficult, and the soils are usually highly moistened, marsh landscapes prevail in the northern provinces, and landscapes formed under the influence of saline groundwater in the south. Thus, the nature and density of relief dissection play a much greater role here than on the Russian Plain in the distribution of soils and vegetation cover, causing significant differences in the regime of soil moisture.

Therefore, there are, as it were, two independent systems of latitudinal zonality in the country: the zonality of drained areas and the zonality of undrained interfluves. These differences are most clearly manifested in the nature of the soils. So, in the drained areas of the forest-bog zone, mainly strongly podzolized soils are formed under the coniferous taiga and soddy-podzolic soils under the birch forests, and in neighboring undrained places - thick podzols, marsh and meadow-bog soils. The drained spaces of the forest-steppe zone are mostly occupied by leached and degraded chernozems or dark gray podzolized soils under birch groves; in undrained areas, they are replaced by marsh, saline or meadow-chernozem soils. In the upland areas of the steppe zone, either ordinary chernozems, which are characterized by increased obesity, low thickness, and linguality (heterogeneity) of soil horizons, or chestnut soils predominate; in poorly drained areas, they usually include spots of solods and solodized solonetzes or solonetsous meadow-steppe soils.

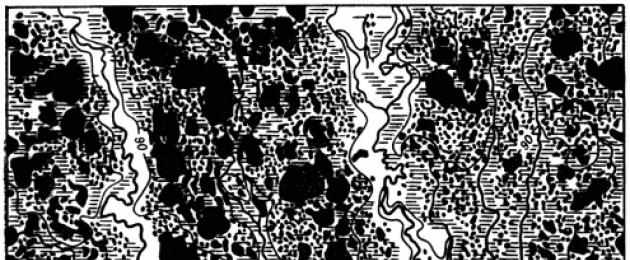

Fragment of a section of swampy taiga in Surgut Polissya (according to V. I. Orlov)

There are some other features that distinguish the zones of Western Siberia from the zones of the Russian Plain. In the tundra zone, which extends much further north than on the Russian Plain, large areas are occupied by arctic tundra, which are absent in the mainland regions of the European part of the Union. The woody vegetation of the forest-tundra is represented mainly by Siberian larch, and not by spruce, as in the regions lying west of the Urals.

In the forest-bog zone, 60% of the area of which is occupied by swamps and poorly drained swampy forests 1, pine forests occupy 24.5% of the forested area, and birch forests (22.6%), mainly secondary ones, predominate. Smaller areas are covered with damp dark coniferous cedar taiga (Pinus sibirica), fir (Abies sibirica) and ate (Picea obovata). Broad-leaved species (with the exception of linden, occasionally found in the southern regions) are absent in the forests of Western Siberia, and therefore there is no zone of broad-leaved forests here.

1 It is for this reason that the zone in Western Siberia is called the forest-bog zone.

An increase in the continentality of the climate causes a relatively sharp transition, compared to the Russian Plain, from forest-bog landscapes to dry steppe spaces in the southern regions of the West Siberian Plain. Therefore, the width of the forest-steppe zone in Western Siberia is much less than on the Russian Plain, and of the tree species it contains mainly birch and aspen.

The West Siberian Plain is wholly part of the transitional Eurosiberian zoogeographic subregion of the Palearctic. 478 species of vertebrates are known here, of which 80 species are mammals. The fauna of the country is young and in its composition differs little from the fauna of the Russian Plain. Only in eastern half countries, some eastern, trans-Yenisei forms are found: the Dzungarian hamster (Phodopus sungorus), chipmunk (Eutamias sibiricus) etc. In last years the fauna of Western Siberia was enriched by muskrats acclimatized here (Ondatra zibethica), hare-hare (Lepus europaeus), American mink (Lutreola vison), teleutka squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris exalbidus), and carp were introduced into its reservoirs (Cyprinus carpio) and bream (Abramis brama).

Natural resources

See photos of the nature of the West Siberian Plain: the Taz Peninsula and the Middle Ob in the Nature of the World section.

The natural wealth of Western Siberia has long served as the basis for the development of various sectors of the economy. There are tens of millions of hectares of good arable land here. Particularly valuable are the lands of the steppe and forest steppe zones with their favorable conditions for Agriculture climate and highly fertile chernozems, gray forest and non-saline chestnut soils, which occupy more than 10% of the country's area. Due to the flatness of the relief, the development of the lands of the southern part of Western Siberia does not require large capital expenditures. For this reason, they were one of the priority areas for the development of virgin and fallow lands; in recent years, more than 15 million hectares have been involved in crop rotation. ha new lands, the production of grain and industrial crops (sugar beet, sunflower, etc.) increased. The lands located to the north, even in the southern taiga zone, are still underused and are a good reserve for development in the coming years. However, this will require much greater expenditures of labor and funds for draining, uprooting and clearing land from shrubs.

The pastures of the forest-bog, forest-steppe and steppe zones are of high economic value, especially water meadows along the valleys of the Ob, Irtysh, Yenisei and their large tributaries. The abundance of natural meadows here creates a solid base for the further development of animal husbandry and a significant increase in its productivity. Moss pastures of the tundra and forest-tundra, occupying more than 20 million hectares in Western Siberia, are of great importance for the development of reindeer breeding. ha; more than half a million domestic deer graze on them.

A significant part of the plain is occupied by forests - birch, pine, cedar, fir, spruce and larch. The total forested area in Western Siberia exceeds 80 million hectares. ha; timber reserves of about 10 billion m 3, and its annual growth is over 10 million tons. m 3 . The most valuable forests are located here, which provide wood for various industries. National economy. The forests along the valleys of the Ob, the lower reaches of the Irtysh and some of their navigable or raftable tributaries are currently most widely used. But many forests, including especially valuable massifs of condo pine, located between the Urals and the Ob, are still poorly developed.

Dozens of large rivers of Western Siberia and hundreds of their tributaries serve as important shipping routes connecting the southern regions with the far north. The total length of navigable rivers exceeds 25,000 km. km. Approximately the same is the length of the rivers along which timber is rafted. The full-flowing rivers of the country (Yenisei, Ob, Irtysh, Tom, etc.) have large energy resources; if fully utilized, they could generate more than $200 billion. kWh electricity per year. The first large Novosibirsk hydroelectric power station on the Ob River with a capacity of 400,000 kWh. kW entered service in 1959; above it, a reservoir with an area of 1070 km 2. In the future, it is planned to build a hydroelectric power station on the Yenisei (Osinovskaya, Igarskaya), in the upper reaches of the Ob (Kamenskaya, Baturinskaya), on the Tom (Tomskaya).

The waters of the large West Siberian rivers can also be used for irrigation and watering of the semi-desert and desert regions of Kazakhstan and Central Asia, which are already experiencing a significant shortage of water resources. Currently, design organizations are developing the main provisions and a feasibility study for the transfer of part of the flow of Siberian rivers to the Aral Sea basin. According to preliminary studies, the implementation of the first stage of this project should provide an annual transfer of 25 km 3 waters from Western Siberia to Central Asia. To this end, on the Irtysh, near Tobolsk, it is planned to create a large reservoir. From it, to the south along the Tobol valley and along the Turgai depression into the Syrdarya basin, the Ob-Caspian canal, more than 1500 meters long, will go to the reservoirs created there. km. The rise of water to the Tobol-Aral watershed is supposed to be carried out by a system of powerful pumping stations.

At the next stages of the project, the volume of water transferred annually can be increased to 60-80 km 3 . Since the waters of the Irtysh and Tobol will no longer be enough for this, the work of the second stage involves the construction of dams and reservoirs on the upper Ob, and possibly on the Chulym and Yenisei.

Naturally, the withdrawal of tens of cubic kilometers of water from the Ob and Irtysh should affect the regime of these rivers in their middle and lower reaches, as well as changes in the landscapes of the territories adjacent to the projected reservoirs and transfer channels. Forecasting the nature of these changes now occupies a prominent place in the scientific research of Siberian geographers.

Quite recently, many geologists, based on the idea of the uniformity of the thick strata of loose deposits that make up the plain and the apparent simplicity of its tectonic structure, very carefully assessed the possibility of discovering any valuable minerals in its depths. However, the geological and geophysical studies carried out in recent decades, accompanied by the drilling of deep wells, have shown the erroneousness of previous ideas about the poverty of the country in minerals and made it possible to imagine the prospects for the use of its mineral resources in a completely new way.

As a result of these studies, more than 120 oil fields have already been discovered in the strata of the Mesozoic (mainly Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous) deposits of the central regions of Western Siberia. The main oil-bearing areas are located in the Middle Ob region - in Nizhnevartovsk (including the Samotlor field, which can produce oil up to 100-120 million tons). t/year), Surgut (Ust-Balykskoe, Zapadno-Surgutskoe, etc.) and Yuzhno-Balyksky (Mamontovskoe, Pravdinskoe, etc.) districts. In addition, there are deposits in the Shaim region, in the Ural part of the plain.

In recent years, in the north of Western Siberia - in the lower reaches of the Ob, Taz and Yamal - the largest deposits of natural gas have also been discovered. The potential reserves of some of them (Urengoy, Medvezhye, Zapolyarny) amount to several trillion cubic meters; gas production at each can reach 75-100 billion cubic meters. m 3 per year. In general, the predicted gas reserves in the depths of Western Siberia are estimated at 40-50 trillion. m 3 , including categories A + B + C 1 - more than 10 trillion. m 3 .

Oil and gas fields Western Siberia

The discovery of both oil and gas fields is of great importance for the development of the economy of Western Siberia and neighboring economic regions. Tyumen and Tomsk region turn into important areas of oil production, oil refining and chemical industry. Already in 1975, more than 145 million tons of oil were mined here. T oil and tens of billions of cubic meters of gas. Oil pipelines Ust-Balyk - Omsk (965 km), Shaim - Tyumen (436 km), Samotlor - Ust-Balyk - Kurgan - Ufa - Almetyevsk, through which oil got out to European part USSR - to the places of its greatest consumption. For the same purpose, the Tyumen-Surgut railway and gas pipelines were built, through which natural gas from West Siberian deposits goes to the Urals, as well as to the central and northwestern regions of the European part of the Soviet Union. In the last five-year plan, the construction of the giant supergas pipeline Siberia - Moscow (its length is more than 3,000 km) was completed. km), through which gas from the Medvezhye field is supplied to Moscow. In the future, gas from Western Siberia will go through pipelines to the countries of Western Europe.

Brown coal deposits have also become known, confined to the Mesozoic and Neogene deposits of the marginal regions of the plain (North-Sosva, Yenisei-Chulym and Ob-Irtysh basins). Western Siberia also has colossal peat reserves. In its peatlands, the total area of which exceeds 36.5 million hectares. ha, concluded a little less than 90 billion. T air-dry peat. This is almost 60% of all peat resources of the USSR.

Geological research led to the discovery of the deposit and other minerals. In the southeast, in the Upper Cretaceous and Paleogene sandstones of the vicinity of Kolpashev and Bakchar, large deposits of oolitic iron ores have been discovered. They lie relatively shallow (150-400 m), the iron content in them is up to 36-45%, and the predicted geological reserves of the West Siberian iron ore basin are estimated at 300-350 billion tons. T, including in one Bakcharskoye field - 40 billion cubic meters. T. Numerous salt lakes in the south of Western Siberia contain hundreds of millions of tons of common and Glauber's salt, as well as tens of millions of tons of soda. In addition, Western Siberia has huge reserves of raw materials for the production of building materials (sand, clay, marls); on its western and southern outskirts there are deposits of limestones, granites, diabases.

Western Siberia is one of the most important economic and geographical regions of the USSR. About 14 million people live on its territory (the average population density is 5 people per 1 km 2) (1976). In cities and workers' settlements there are machine-building, oil refineries and chemical plants, enterprises of the timber, light and food industries. Various branches of agriculture are of great importance in the economy of Western Siberia. It produces about 20% of the commercial grain of the USSR, a significant amount of various industrial crops, a lot of butter, meat and wool.

The decisions of the 25th Congress of the CPSU outlined further gigantic growth in the economy of Western Siberia and a significant increase in its importance in the economy of our country. In the coming years, it is planned to create new energy bases within its borders based on the use of cheap coal deposits and hydropower resources of the Yenisei and Ob, develop the oil and gas industry, and create new centers of mechanical engineering and chemistry.

The main directions of development of the national economy plan to continue the formation of the West Siberian territorial production complex, to turn Western Siberia into the USSR's main oil and gas production base. In 1980, 300-310 million tons will be produced here. T oil and up to 125-155 billion m 3 natural gas (about 30% of gas production in our country).

It is planned to continue the construction of the Tomsk petrochemical complex, put into operation the first stage of the Achinsk oil refinery, expand the construction of the Tobolsk petrochemical complex, build plants for processing petroleum gas, a system of powerful pipelines for transporting oil and gas from the northwestern regions of Western Siberia to the European part of the USSR and to oil refineries in the eastern regions of the country, as well as the Surgut-Nizhnevartovsk railway and to begin construction of the Surgut-Urengoi railway. The tasks of the five-year plan provide for accelerating the exploration of oil, natural gas and condensate fields in the Middle Ob and in the north of the Tyumen region. The harvesting of timber, the production of grain and livestock products will also increase substantially. In the southern regions of the country, it is planned to carry out a number of major land reclamation measures - to irrigate and water large areas of land in the Kulunda and Irtysh regions, to begin construction of the second stage of the Aley system and the Charysh group water pipeline, and to build drainage systems in Baraba.

,WESTERN SIBERIAN PLAIN, The West Siberian Lowland, one of the largest plains in the world (the third largest after the Amazonian and East European plains), is located in the north of Asia, in Russia and Kazakhstan. It occupies the whole of Western Siberia, stretching from the coast of the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Turgai plateau and the Kazakh uplands in the south, from the Urals in the west to the Central Siberian plateau in the east. The length from north to south is up to 2500 km, from west to east from 900 km in (north) to 2000 (in south). The area is about 3 million km 2, including 2.6 million km 2 in Russia. The prevailing heights do not exceed 150 m. The lowest parts of the plain (50–100 m) are located mainly in its central (Kondinskaya and Sredneobskaya lowlands) and northern (Nizhneobskaya, Nadymskaya and Purskaya lowlands) parts. The highest point of the West Siberian Plain - up to 317 m - is located on the Priobsky Plateau.

At the base of the West Siberian Plain lies West Siberian platform. To the east it borders on Siberian platform, in the south - with Paleozoic structures of Central Kazakhstan, the Altai-Sayan region, in the west - with the folded system of the Urals.

Relief

The surface is a low accumulative plain with a rather uniform relief (more uniform than that of the East European Plain), the main elements of which are wide flat interfluves and river valleys; various forms of manifestation of permafrost (common up to 59 ° N), increased waterlogging, and developed (mainly in the south in loose rocks and soils) ancient and modern salt accumulation are characteristic. In the north, in the area of distribution of marine accumulative and moraine plains (Nadymskaya and Purskaya lowlands), the general flatness of the territory is disturbed by moraine gently sloping and hilly-sloping (North-Sosvinskaya, Lyulimvor, Verkhne-, Srednetazovskaya, etc.) uplands 200–300 m high, the southern boundary of which runs around 61–62 ° N. sh.; they are horseshoe-shaped covered from the south by flat-topped uplands, including the Poluyskaya Upland, Belogorsky Mainland, Tobolsky Mainland, Siberian Uvaly (245 m), etc. In the north, permafrost exogenous processes (thermal erosion, heaving of soils, solifluction) are widespread, deflation is common on sandy surfaces, in swamps - peat accumulation. Permafrost is ubiquitous on the Yamal, Tazovsky, and Gydansky peninsulas; the thickness of the frozen layer is very significant (up to 300–600 m).

To the south, the area of moraine relief is adjoined by flat lacustrine and lacustrine-alluvial lowlands, the lowest (40–80 m high) and swampy of which are the Konda lowland and the Sredneobskaya lowland with the Surgut lowland (105 m high). This territory, not covered by the Quaternary glaciation (to the south of the line Ivdel - Ishim - Novosibirsk - Tomsk - Krasnoyarsk), is a poorly dissected denudation plain, rising up to 250 m to the west, to the foothills of the Urals. In the interfluve of the Tobol and the Irtysh, there is an inclined, in places with ridges, lacustrine-alluvial Ishim Plain(120–220 m) with a thin cover of loess-like loams and loess occurring on salt-bearing clays. It is adjacent to alluvial Baraba lowland, Vasyugan Plain and Kulunda Plain, where the processes of deflation and modern salt accumulation are developed. In the foothills of Altai - the Ob plateau and the Chulym plain.

On the geological structure and minerals, see Art. West Siberian platform ,

Climate

The West Siberian Plain is dominated by a harsh continental climate. The significant length of the territory from north to south determines the well-defined latitudinal zonality of the climate and noticeable differences in the climatic conditions of the northern and southern parts of the plain. The nature of the climate is significantly influenced by the Arctic Ocean, as well as the flat relief, which contributes to the unhindered exchange of air masses between north and south. Winter in the polar latitudes is severe and lasts up to 8 months (the polar night lasts almost 3 months); the average January temperature is from -23 to -30 °C. In the central part of the plain, winter lasts almost 7 months; the average January temperature is from -20 to -22 °C. In the southern part of the plain, where the influence of the Asian anticyclone is increasing, at the same average monthly temperatures, winter is shorter - 5–6 months. Minimum air temperature -56 °C. The duration of snow cover in the northern regions reaches 240–270 days, and in the southern regions - 160–170 days. The thickness of the snow cover in the tundra and steppe zones is 20–40 cm; in the forest zone, from 50–60 cm in the west to 70–100 cm in the east. In summer, the western transfer of Atlantic air masses predominates with intrusions of cold Arctic air in the north, and dry warm air masses from Kazakhstan and Central Asia in the south. In the north of the plain, summer, which occurs under polar day conditions, is short, cool, and humid; in the central part - moderately warm and humid, in the south - arid and dry with dry winds and dust storms. The average July temperature rises from 5°C in the Far North to 21–22°C in the south. The duration of the growing season in the south is 175–180 days. Atmospheric precipitation falls mainly in summer (from May to October - up to 80% of precipitation). Most precipitation - up to 600 mm per year - falls in the forest zone; the wettest are the Kondinskaya and Sredneobskaya lowlands. To the north and south, in the tundra and steppe zone, the annual precipitation gradually decreases to 250 mm.

surface water

On the territory of the West Siberian Plain, more than 2,000 rivers flow, belonging to the basin of the Arctic Ocean. Their total flow is about 1200 km 3 of water per year; up to 80% of the annual runoff occurs in spring and summer. The largest rivers - the Ob, Yenisei, Irtysh, Taz and their tributaries - flow in well developed deep (up to 50–80 m) valleys with a steep right bank and a system of low terraces on the left bank. The feeding of the rivers is mixed (snow and rain), the spring flood is extended, the low water is long summer-autumn and winter. All rivers are characterized by slight slopes and low flow rates. The ice cover on the rivers lasts up to 8 months in the north, up to 5 months in the south. Large rivers are navigable, are important rafting and transportation routes, and, in addition, have large reserves of hydropower resources.

There are about 1 million lakes on the West Siberian Plain, the total area of which is more than 100 thousand km2. The largest lakes are Chany, Ubinskoye, Kulundinskoye, and others. Lakes of thermokarst and moraine-glacial origin are widespread in the north. There are many small lakes in the suffusion depressions (less than 1 km 2): on the interfluve of the Tobol and Irtysh - more than 1500, on the Baraba lowland - 2500, among them there are many fresh, salty and bitter-salty ones; there are self-sustaining lakes. The West Siberian Plain is distinguished by a record number of swamps per unit area (the area of the wetland is about 800 thousand km 2).

Landscape types

The uniformity of the relief of the vast West Siberian Plain determines the clearly pronounced latitudinal zonality of landscapes, although, compared with the East European Plain, the natural zones here are shifted to the north; landscape differences within the zones are less noticeable than on the East European Plain, and the zone of broad-leaved forests is absent. Due to the poor drainage of the territory, hydromorphic complexes play a prominent role: swamps and swampy forests occupy about 128 million hectares here, and in the steppe and forest-steppe zones there are many solonetzes, solods and solonchaks.

On the Yamal, Tazovsky and Gydansky peninsulas, in conditions of continuous permafrost, landscapes of arctic and subarctic tundra with moss, lichen and shrub (dwarf birch, willow, alder) vegetation have formed on gleyzems, peat-gleyzems, peat-podburs and soddy soils. Polygonal grass-hypnum swamps are widespread. The share of primary landscapes is extremely insignificant. To the south, tundra landscapes and swamps (mostly flat-hummocky) are combined with larch and spruce-larch light forests on podzolic-gley and peat-podzolic-gley soils, forming a narrow forest-tundra zone, transitional to the forest (forest-bog) zone of the temperate zone, represented by subzones of the northern, middle and southern taiga. Swampiness is common to all subzones: over 50% of the area of the northern taiga, about 70% of the middle taiga, and about 50% of the southern taiga. The northern taiga is characterized by flat and large hillocky raised bogs, the middle taiga is characterized by ridge-hollow and ridge-lake bogs, the southern taiga is characterized by ridge-hollow, pine-shrub-sphagnum, transitional sedge-sphagnum and low-lying tree-sedge bogs. The largest swamp Vasyugan Plain. The forest complexes of different subzones, formed on slopes with different degrees of drainage, are peculiar.

Northern taiga forests on permafrost are represented by sparse low-growing, heavily waterlogged, pine, pine-spruce and spruce-fir forests on gley-podzolic and podzolic-gley soils. The indigenous landscapes of the northern taiga occupy 11% of the plain area. Indigenous landscapes in the middle taiga occupy 6% of the area of the West Siberian Plain, in the southern - 4%. Common to the forest landscapes of the middle and southern taiga is the wide distribution of lichen and shrub-sphagnum pine forests on sandy and sandy loamy illuvial-ferruginous and illuvial-humus podzols. On loams in the middle taiga, along with extensive swamps, spruce-cedar forests with larch and birch forests are developed on podzolic, podzolic-gley, peat-podzolic-gley and gley peat-podzols.

In the subzone of the southern taiga on loams - spruce-fir and fir-cedar (including urman - dense dark coniferous forests with a predominance of fir) small-grass forests and birch forests with aspen on sod-podzolic and sod-podzolic-gley (including with a second humus horizon) and peat-podzolic-gley soils.

The subtaiga zone is represented by park pine, birch and birch-aspen forests on gray, gray gley and soddy-podzolic soils (including those with a second humus horizon) in combination with steppe meadows on cryptogley chernozems, solonetsous in places. Indigenous forest and meadow landscapes are practically not preserved. Boggy forests turn into lowland sedge-hypnum (with ryams) and sedge-reed bogs (about 40% of the zone). Forest-steppe landscapes of sloping plains with loess-like and loess covers on salt-bearing tertiary clays are characterized by birch and aspen-birch groves on gray soils and solods in combination with forb-grass steppe meadows on leached and cryptogleyed chernozems, to the south - with meadow steppes on ordinary chernozems, in places solonetzic and saline. On the sands are pine forests. Up to 20% of the zone is occupied by eutrophic reed-sedge bogs. In the steppe zone, the primary landscapes have not been preserved; in the past, these were forb-feather grass steppe meadows on ordinary and southern chernozems, sometimes saline, and in drier southern regions - fescue-feather grass steppes on chestnut and cryptogley soils, gley solonetzes and solonchaks.

Environmental issues and protected natural areas

In areas of oil production due to pipeline breaks, water and soil are polluted with oil and oil products. In forestry areas - overcutting, waterlogging, the spread of silkworms, fires. In agrolandscapes, there is an acute problem of lack of fresh water, secondary salinization of soils, destruction of soil structure and loss of soil fertility during plowing, drought and dust storms. In the north, there is degradation of reindeer pastures, in particular due to overgrazing, which leads to a sharp reduction in their biodiversity. No less important is the problem of preserving hunting grounds and habitats of fauna.

To study and protect typical and rare natural landscapes Numerous reserves, national and natural parks have been created. Among the largest reserves: in the tundra - the Gydansky reserve, in the northern taiga - the Verkhnetazovsky reserve, in the middle taiga - the Yugansky reserve and Malaya Sosva, etc. The national park Pripyshminsky Bory was created in the subtaiga. Natural parks are also organized: in the tundra - Deer streams, in the north. taiga - Numto, Siberian Ridges, in the middle taiga - Kondinsky lakes, in the forest-steppe - Bird's harbor.

The first acquaintance of Russians with Western Siberia took place, probably, as early as the 11th century, when the Novgorodians visited the lower reaches of the Ob River. With the campaign of Yermak (1582–85), a period of discoveries began in Siberia and the development of its territory.

The West Siberian Plain is one of the largest accumulative low-lying plains of the globe. It stretches from the shores of the Kara Sea to the steppes of Kazakhstan and from the Urals in the west to the Central Siberian Plateau in the east. The comparative uniformity of the relief (Fig. 3) determines the distinct zonality of the landscapes of Western Siberia, from tundra in the north to steppe in the south (Fig. 4). Due to the poor drainage of the territory within its boundaries, hydromorphic complexes play a very prominent role: swamps and swampy forests occupy a total of about 128 million hectares, and there are many solonetzes, solods and solonchaks in the steppe and forest-steppe zones. The plain has the shape of a trapezoid tapering to the north: the distance from its southern border to the northern reaches almost 2500 km, the width is from 800 to 1900 km, and the area is only slightly less than 3 million km2.

The geographical position of the West Siberian Plain determines the transitional nature of its climate between the temperate continental climate of the Russian Plain and the sharply continental climate of Central Siberia. Therefore, the landscapes of the country are distinguished by a number of peculiar features: the natural zones here are somewhat shifted to the north compared to the Russian Plain, there is no zone of broad-leaved forests, and landscape differences within the zones are less noticeable than on the Russian Plain. The West Siberian Plain is the most inhabited and developed (especially in the south) part of Siberia. Within its boundaries are located Tyumen, Kurgan, Omsk, Novosibirsk, Tomsk, a significant part of the Altai Territory, as well as some eastern regions of the Sverdlovsk and Chelyabinsk regions and the western regions of the Krasnoyarsk Territory.

Rice. 3

Rice. 4

Provinces: 1 - Yamail; 2 - Tazovskaya; 3 - Gydanskaya; 4 - Obsko-Tazovskaya; 5 - Yenisei-Tazovskaya; 6 - Severososvinskaya; 7 - Obsko-Purskaya; 8 - Yenisei: 9 - Poduralskaya; 10 - Sredneobskaya; 11 - Vasyugan; 12 - Chulym-Yenisei; 13 - Nezhneobskaya; 14 - Zauralskaya; 15 - Priishimskaya; 16 - Barabinskaya; 17 - Verkhneobskaya; 18 - Priturgayskaya; 19 - Priirtyshskaya; 20 - Kulundiskaya.

The acquaintance of Russians with Western Siberia took place for the first time, probably, as early as the 11th century, when the Novgorodians visited the lower reaches of the Ob. The campaign of Yermak (1581-1584) opens the brilliant period of the Great Russians geographical discoveries in Siberia and the development of its territory. However, the scientific study of the nature of the country began only in the 18th century, when detachments of the Great Northern expedition and then academic expeditions were sent here. In the 19th century Russian scientists and engineers are studying the conditions of navigation on the Ob, Yenisei and the Kara Sea, the geological and geographical features of the route of the Siberian railway that was being designed at that time, salt deposits in the steppe zone. A significant contribution to the knowledge of the West Siberian taiga and steppes was made by studies of soil-botanical expeditions of the Migration Administration, undertaken in 1908-1914. in order to study the conditions for the agricultural development of plots allocated for the resettlement of peasants from European Russia.

The study of the nature and natural resources of Western Siberia acquired a completely different scope after the Great October Revolution. In the research that was necessary for the development of the productive forces, no longer individual specialists or small detachments took part, but hundreds of large complex expeditions and many scientific institutes created in various cities of Western Siberia. Detailed and versatile studies were carried out here by the USSR Academy of Sciences (Kulunda, Baraba, Gydan and other expeditions) and its Siberian branch, the West Siberian Geological Administration, geological institutes, expeditions of the Ministry of Agriculture, Hydroproject and other organizations. As a result of these studies, ideas about the country's relief have changed significantly, detailed soil maps of many regions of Western Siberia have been compiled, and measures have been developed for the rational use of saline soils and the famous West Siberian chernozems. Of great practical importance were the forest typological studies of Siberian geobotanists, the study of peat bogs and tundra pastures. But especially significant results were brought by the work of geologists. Deep drilling and special geophysical studies have shown that the depths of many regions of Western Siberia contain the richest deposits of natural gas, large reserves of iron ore, brown coal and many other minerals, which already serve as a solid base for the development of industry in Western Siberia.

Eastern territories of Russian Asia open from Ural mountains view of the West Siberian Plain. Its settlement by Russians began in the 16th century, from the time of Yermak's campaign. The path of the expedition ran from the south of the plain.

These areas are still the most densely populated. However, it must be remembered that already in the 11th century the Novgorodians established trade relations with a population on the lower reaches of the Ob.

Geographical position

The West Siberian Plain is washed by the harsh Kara Sea from the north. In the east, along the border of the Yenisei River basin, it is adjacent to the Central Siberian Plateau. The southeast is guarded by the snowy foothills of Altai. In the south, the Kazakh uplands became the boundary of the flat territories. The western border, as mentioned above, are the oldest mountains of Eurasia - the Urals.

Relief and landscape of the plain: features

The unique feature of the plain is that all the heights on it are very weakly expressed, both in absolute and in relative terms. The terrain of the West Siberian Plain is very low-lying, with many river channels, swampy over 70 percent of the territory.

The lowland stretches from the shores of the Arctic Ocean to southern steppes Kazakhstan and almost all of it is located within the territory of our country. The plain provides a unique opportunity to see five natural zones at once with their characteristic landscape and climate conditions.

The relief is typical for low-lying river basins. Small hills alternating with swamps occupy the interfluve areas. The area with saline groundwater dominates in the south.

Natural areas, cities and plain regions

Western Siberia is represented by five natural zones.

(Swampy area in the tundra of the Vasyugan swamps, Tomsk region)

The tundra occupies a narrow strip of the north of the Tyumen region and almost immediately passes into the forest tundra. In the extreme northern areas, one can find arrays of a combination of lichens, mosses of Western Siberia. The swampy terrain prevails, turning into light forest forest-tundra. The vegetation here is larch and thickets of shrubs.

The taiga of Western Siberia is characterized by dark coniferous zones with a variety of cedar, northern spruce and fir. Occasionally, pine forests can be found, occupying areas between swamps. Most of the lowland landscape is occupied by endless swamps. One way or another, the whole of Western Siberia is characterized by swampiness, but there is also a unique natural massif here - the largest swamp in the world, Vasyuganskoye. It occupied large territories in the southern taiga.

(forest-steppe)

Closer to the south, nature changes - the taiga brightens, turning into a forest-steppe. Aspen-birch forests and meadows with copses appear. The Ob basin is adorned with natural island pine forests.

The steppe zone occupies the south of the Omsk and South western part Novosibirsk regions. Also, the steppe distribution area reaches the western part of the Altai Territory, which includes the Kulundinskaya, Aleiskaya and Biyskaya steppes. The territory of ancient water drains is occupied by pine forests

(Fields in the taiga of the Tyumen region, Yugra)

The West Siberian Plain provides an opportunity for active land use. It is very rich in oil and almost all lined with mining towers. The developed economy of the region attracts new residents. Large cities of the northern and central parts of the West Siberian Plain are well known: Urengoy, Nefteyugansk, Nizhnevartovsk. In the south of the city of Tomsk, Tyumen, Kurgan, Omsk.

Rivers and lakes of the plains

(The Yenisei River in hilly-flat terrain)

Rivers flowing through the territory of the West Siberian Lowland flow into the Kara Sea. The Ob is not only the longest river of the plain, but together with the Irtysh tributary, it is the longest waterway in Russia. However, there are rivers on the plain that do not belong to the Ob basin - Nadym, Pur, Taz and Tobol.

The area is rich in lakes. They are divided into two groups according to the nature of their occurrence: part was formed in pits dug by a glacier that passed through the lowland, part - in places of ancient swamps. The area holds the world record for wetlands.

Plain climate

Western Siberia in its north is covered with permafrost. A continental climate is observed throughout the plain. Most of the territory of the plain is very susceptible to the influence of its formidable neighbor - the Arctic Ocean, whose air masses freely dominate the lowland region. Its cyclones dictate the regime of precipitation and temperatures. In the plains, where the arctic, subarctic and temperate zones converge, cyclones often occur, leading to rain. In winter, cyclones generated at the junctions of the temperate and arctic zones soften the frosts in the north of the plains.

More precipitation falls in the north of the plain - up to 600 ml per year. The temperature in the north in January, on average, does not rise above 22 ° C of frost, in the south at the same time frost reaches 16 ° C. In July, in the north and south of the plain, respectively, 4 ° C and 22 ° C.

GIOWest Siberian Plain- the plain is located in the north of Asia, occupies the entire western part of Siberia from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Central Siberian Plateau in the east. In the north it is bounded by the coast of the Kara Sea, in the south it extends to the Kazakh uplands, in the southeast the West Siberian Plain, gradually rising, is replaced by the foothills of Altai, Salair, Kuznetsk Altai and Mountain Shoria. The plain has the shape of a trapezoid narrowing to the north: the distance from its southern border to the northern reaches almost 2500 km, the width is from 800 to 1900 km, and the area is only slightly less than 3 million km².

The West Siberian Plain is the most inhabited and developed (especially in the south) part of Siberia. Within its boundaries are located Tyumen, Kurgan, Omsk, Novosibirsk and Tomsk regions, Yamalo-Nenets and Khanty-Mansiysk autonomous regions, the eastern regions of the Sverdlovsk and Chelyabinsk regions, a significant part of the Altai Territory, the western regions of the Krasnoyarsk Territory (about 1/7 of the area of Russia). In the Kazakh part, within its boundaries, there are areas of North Kazakhstan, Akmola, [[Pavlodar region | Pavlodar], Kustanai and East Kazakhstan regions of Kazakhstan.

Relief and geological structure

The surface of the West Siberian Lowland is flat with a rather insignificant elevation difference. However, the relief of the plain is quite diverse. The lowest parts of the plain (50-100 m) are located mainly in the central (Kondinskaya and Sredneobskaya lowlands) and northern (Nizhneobskaya, Nadymskaya and Purskaya lowlands) parts of it. Low (up to 200-250 m) elevations stretch along the western, southern and eastern outskirts: North Sosvinskaya and Turinskaya, Ishimskaya plain, Priobskoye and Chulym-Yenisei plateau, Ketsko-Tymskaya, Upper Taz and Lower Yenisei uplands. A distinctly pronounced strip of hills is formed in the inner part of the plain by the Siberian Uvaly (average height - 140-150 m), extending from the west from the Ob to the east to the Yenisei, and the Vasyugan plain parallel to them.

The relief of the plain is largely due to its geological structure. At the base of the West Siberian Plain lies the epihercynian West Siberian plate, the foundation of which is composed of intensely dislocated Paleozoic deposits. The formation of the West Siberian Plate began in the Upper Jurassic, when, as a result of breaking, destruction and regeneration, a huge territory between the Urals and the Siberian platform sank, and a huge sedimentary basin arose. In the course of its development, the West Siberian Plate was captured more than once by marine transgressions. At the end of the Lower Oligocene, the sea left the West Siberian plate, and it turned into a huge lacustrine-alluvial plain. In the middle and late Oligocene and Neogene, the northern part of the plate experienced uplift, which was replaced by subsidence in the Quaternary. The general course of the development of the plate with the subsidence of colossal spaces resembles the process of oceanization that has not reached its end. This feature of the plate is emphasized by the phenomenal development of waterlogging.

Separate geological structures, despite a thick layer of sediments, are reflected in the relief of the plain: for example, the Verkhnetazovsky and Lyulimvor uplands correspond to gentle anticlines, for example, and the Baraba and Kondinsky lowlands are confined to the syneclises of the basement of the plate. However, discordant (inversion) morphostructures are also not uncommon in Western Siberia. These include, for example, the Vasyugan Plain, which formed on the site of a gentle syneclise, and the Chulym-Yenisei Plateau, located in the basement trough zone.

The cuff of loose deposits contains groundwater horizons - fresh and mineralized (including brine), hot (up to 100-150 ° C) waters are also found. There are industrial deposits of oil and natural gas (West Siberian oil and gas basin). In the area of the Khanty-Mansiysk syneclise, Krasnoselsky, Salymsky and Surgutsky regions, in the layers of the Bazhenov formation at a depth of 2 km, there are the largest shale oil reserves in Russia.

Climate

West Siberian Plain. Spill of the rivers Taz and Ob. July, 2002

The West Siberian Plain is characterized by a harsh, fairly continental climate. Its great length from north to south determines the distinct zoning of the climate and significant differences in climatic conditions in the northern and southern parts of Western Siberia. The proximity of the Arctic Ocean also significantly influences the continental climate of Western Siberia. The flat relief contributes to the exchange of air masses between its northern and southern regions.

During the cold period, within the plain, there is an interaction between the area of relatively high atmospheric pressure, located above the southern part of the plain, and the area of low pressure, which in the first half of winter extends in the form of a hollow of the Icelandic baric minimum over the Kara Sea and the northern peninsulas. In winter, masses of continental air of temperate latitudes predominate, which come from Eastern Siberia or are formed on the spot as a result of air cooling over the territory of the plain.