On the surface of the Earth, meteorology deals with long-term variations - climatology.

The thickness of the atmosphere is 1500 km from the Earth's surface. The total mass of air, that is, a mixture of gases that make up the atmosphere, is 5.1-5.3 * 10 ^ 15 tons. The molecular weight of clean dry air is 29. The pressure at 0 ° C at sea level is 101,325 Pa, or 760 mm. rt. Art.; critical temperature - 140.7 °C; critical pressure 3.7 MPa. The solubility of air in water at 0 ° C is 0.036%, at 25 ° C - 0.22%.

The physical state atmosphere is determined. The main parameters of the atmosphere: air density, pressure, temperature and composition. As altitude increases, air density decreases. The temperature also changes with the change in altitude. Vertical is characterized by different thermal and electrical properties, different state air. Depending on the temperature in the atmosphere, the following main layers are distinguished: troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere, exosphere (scattering sphere). The transitional regions of the atmosphere between adjacent shells are called the tropopause, stratopause, etc., respectively.

Troposphere- lower, main, most studied, with a height in the polar regions of 8-10 km, up to 10-12 km, at the equator - 16-18 km. Approximately 80-90% of the total mass of the atmosphere and almost all water vapor are concentrated in the troposphere. When rising every 100 m, the temperature in the troposphere decreases by an average of 0.65 ° C and reaches -53 ° C in the upper part. This upper layer of the troposphere is called the tropopause. In the troposphere, turbulence and convection are highly developed, the predominant part is concentrated, clouds arise, develop.

Stratosphere- layer of the atmosphere, located at an altitude of 11-50 km. A slight change in temperature in the 11-25 km layer (the lower layer of the stratosphere) and its increase in the 25-40 km layer from -56.5 to 0.8 °C (the upper layer of the stratosphere or the inversion region) are typical. Having reached a value of 273 K (0 °C) at an altitude of about 40 km, the temperature remains constant up to an altitude of 55 km. This region of constant temperature is called the stratopause and is the boundary between the stratosphere and the mesosphere.

It is in the stratosphere that the layer is located ozonosphere("ozone layer", at an altitude of 15-20 to 55-60 km), which determines the upper limit of life in. An important component of the stratosphere and mesosphere is ozone, which is formed as a result of photochemical reactions most intensively at an altitude of 30 km. The total mass of ozone at normal pressure would be a layer 1.7-4 mm thick, but even this is enough to absorb ultraviolet, which is harmful to life. The destruction of ozone occurs when it interacts with free radicals, nitric oxide, halogen-containing compounds (including "freons"). Ozone - an allotropy of oxygen, is formed as a result of the following chemical reaction, usually after rain, when the resulting compound rises to the upper layers of the troposphere; ozone has a specific smell.

Most of the short-wavelength part of ultraviolet radiation (180-200 nm) is retained in the stratosphere and the energy of short waves is transformed. Under the influence of these rays, magnetic fields, molecules break up, ionization occurs, new formation of gases and other chemical compounds. These processes can be observed in the form northern lights, lightning, and other glows. There is almost no water vapor in the stratosphere.

Mesosphere starts at an altitude of 50 km and extends up to 80-90 km. to a height of 75-85 km it drops to -88 °С. The upper boundary of the mesosphere is the mesopause.

Thermosphere(another name is the ionosphere) - the layer of the atmosphere following the mesosphere - begins at an altitude of 80-90 km and extends up to 800 km. The air temperature in the thermosphere rapidly and steadily increases and reaches several hundred and even thousands of degrees.

Exosphere- scattering zone, the outer part of the thermosphere, located above 800 km. The gas in the exosphere is highly rarefied, and hence its particles leak into interplanetary space (dissipation).

Up to a height of 100 km, the atmosphere is a homogeneous (single-phase), well-mixed mixture of gases. In higher layers, the distribution of gases in height depends on their molecular weights, the concentration of heavier gases decreases faster with distance from the Earth's surface. Due to the decrease in gas density, the temperature drops from 0 °C in the stratosphere to -110 °C in the mesosphere. but kinetic energy individual particles at altitudes of 200-250 km corresponds to a temperature of approximately 1500 °C. Above 200 km, significant fluctuations in temperature and gas density are observed in time and space.

At an altitude of about 2000-3000 km, the exosphere gradually passes into the so-called near space vacuum, which is filled with highly rarefied particles of interplanetary gas, mainly hydrogen atoms. But this gas is only part of the interplanetary matter. The other part is composed of dust-like particles of cometary and meteoric origin. In addition to these extremely rarefied particles, electromagnetic and corpuscular radiation of solar and galactic origin penetrates into this space.

The troposphere accounts for about 80% of the mass of the atmosphere, the stratosphere accounts for about 20%; the mass of the mesosphere is no more than 0.3%, the thermosphere is less than 0.05% of the total mass of the atmosphere. Based on the electrical properties in the atmosphere, the neutrosphere and ionosphere are distinguished. It is currently believed that the atmosphere extends to an altitude of 2000-3000 km.

Depending on the composition of the gas in the atmosphere, homosphere and heterosphere are distinguished. heterosphere- this is the area where gravity affects the separation of gases, because. their mixing at this height is negligible. Hence follows the variable composition of the heterosphere. Below it lies a well-mixed, homogeneous part of the atmosphere called the homosphere. The boundary between these layers is called the turbopause and lies at an altitude of about 120 km.

Atmospheric pressure is the pressure on the objects in it and the earth's surface. Normal is an indicator of 760 mm Hg. Art. (101 325 Pa). For each kilometer increase in altitude, the pressure drops by 100 mm.

Composition of the atmosphere

The air shell of the Earth, consisting mainly of gases and various impurities (dust, water drops, ice crystals, sea salts, combustion products), the amount of which is not constant. The main gases are nitrogen (78%), oxygen (21%) and argon (0.93%). The concentration of gases that make up the atmosphere is almost constant, except for carbon dioxide CO2 (0.03%).

The atmosphere also contains SO2, CH4, NH3, CO, hydrocarbons, HC1, HF, Hg vapor, I2, as well as NO and many other gases in small quantities. In the troposphere there is constantly a large amount of suspended solid and liquid particles (aerosol).

At 0 °C - 1.0048 10 3 J / (kg K), C v - 0.7159 10 3 J / (kg K) (at 0 °C). The solubility of air in water (by mass) at 0 ° C - 0.0036%, at 25 ° C - 0.0023%.

In addition to the gases indicated in the table, the atmosphere contains Cl 2, SO 2, NH 3, CO, O 3, NO 2, hydrocarbons, HCl,, HBr, vapors, I 2, Br 2, as well as many other gases in minor quantities. In the troposphere there is constantly a large amount of suspended solid and liquid particles (aerosol). Radon (Rn) is the rarest gas in the Earth's atmosphere.

The structure of the atmosphere

boundary layer of the atmosphere

The lower layer of the atmosphere adjacent to the Earth's surface (1-2 km thick) in which the influence of this surface directly affects its dynamics.

Troposphere

Its upper limit is at an altitude of 8-10 km in polar, 10-12 km in temperate and 16-18 km in tropical latitudes; lower in winter than in summer. The lower, main layer of the atmosphere contains more than 80% of the total mass of atmospheric air and about 90% of all water vapor present in the atmosphere. Turbulence and convection are strongly developed in the troposphere, clouds appear, cyclones and anticyclones develop. Temperature decreases with altitude with an average vertical gradient of 0.65°/100 m

tropopause

The transitional layer from the troposphere to the stratosphere, the layer of the atmosphere in which the decrease in temperature with height stops.

Stratosphere

The layer of the atmosphere located at an altitude of 11 to 50 km. A slight change in temperature in the 11-25 km layer (lower layer of the stratosphere) and its increase in the 25-40 km layer from −56.5 to 0.8 ° (upper stratosphere or inversion region) are typical. Having reached a value of about 273 K (almost 0 °C) at an altitude of about 40 km, the temperature remains constant up to an altitude of about 55 km. This region of constant temperature is called the stratopause and is the boundary between the stratosphere and the mesosphere.

Stratopause

The boundary layer of the atmosphere between the stratosphere and the mesosphere. There is a maximum in the vertical temperature distribution (about 0 °C).

Mesosphere

The mesosphere begins at an altitude of 50 km and extends up to 80-90 km. The temperature decreases with height with an average vertical gradient of (0.25-0.3)°/100 m. The main energy process is radiant heat transfer. Complex photochemical processes involving free radicals, vibrationally excited molecules, etc., cause atmospheric luminescence.

mesopause

Transitional layer between mesosphere and thermosphere. There is a minimum in the vertical temperature distribution (about -90 °C).

Karman Line

Altitude above sea level, which is conventionally accepted as the boundary between the Earth's atmosphere and space. According to the FAI definition, the Karman Line is at an altitude of 100 km above sea level.

Thermosphere

The upper limit is about 800 km. The temperature rises to altitudes of 200-300 km, where it reaches values of the order of 1226.85 C, after which it remains almost constant up to high altitudes. Under the influence of solar radiation and cosmic radiation, air is ionized (“ auroras”) - the main regions of the ionosphere lie inside the thermosphere. At altitudes above 300 km, atomic oxygen predominates. The upper limit of the thermosphere is largely determined by the current activity of the Sun. During periods of low activity - for example, in 2008-2009 - there is a noticeable decrease in the size of this layer.

Thermopause

The region of the atmosphere above the thermosphere. In this region, the absorption of solar radiation is insignificant and the temperature does not actually change with height.

Exosphere (scattering sphere)

Up to a height of 100 km, the atmosphere is a homogeneous, well-mixed mixture of gases. In higher layers, the distribution of gases in height depends on their molecular masses, the concentration of heavier gases decreases faster with distance from the Earth's surface. Due to the decrease in gas density, the temperature drops from 0 °C in the stratosphere to −110 °C in the mesosphere. However, the kinetic energy of individual particles at altitudes of 200–250 km corresponds to a temperature of ~150 °C. Above 200 km, significant fluctuations in temperature and gas density are observed in time and space.

At an altitude of about 2000-3500 km, the exosphere gradually passes into the so-called near space vacuum, which is filled with highly rarefied particles of interplanetary gas, mainly hydrogen atoms. But this gas is only part of the interplanetary matter. The other part is composed of dust-like particles of cometary and meteoric origin. In addition to extremely rarefied dust-like particles, electromagnetic and corpuscular radiation of solar and galactic origin penetrates into this space.

Overview

The troposphere accounts for about 80% of the mass of the atmosphere, the stratosphere accounts for about 20%; the mass of the mesosphere - no more than 0.3%, the thermosphere - less than 0.05% of total mass atmosphere.

Based on the electrical properties in the atmosphere, they emit the neutrosphere And ionosphere .

Depending on the composition of the gas in the atmosphere, they emit homosphere And heterosphere. heterosphere- this is an area where gravity affects the separation of gases, since their mixing at such a height is negligible. Hence follows the variable composition of the heterosphere. Below it lies a well-mixed, homogeneous part of the atmosphere, called the homosphere. The boundary between these layers is called turbopause, it lies at an altitude of about 120 km.

Other properties of the atmosphere and effects on the human body

Already at an altitude of 5 km above sea level, an untrained person develops oxygen starvation and, without adaptation, a person's performance is significantly reduced. This is where the physiological zone of the atmosphere ends. Human breathing becomes impossible at an altitude of 9 km, although up to about 115 km the atmosphere contains oxygen.

The atmosphere provides us with the oxygen we need to breathe. However, due to the drop in the total pressure of the atmosphere as you rise to a height, the partial pressure of oxygen also decreases accordingly.

In rarefied layers of air, the propagation of sound is impossible. Up to altitudes of 60-90 km, it is still possible to use air resistance and lift for controlled aerodynamic flight. But starting from altitudes of 100-130 km, the concepts of the M number and the sound barrier familiar to every pilot lose their meaning: there passes the conditional Karman line, beyond which the area of purely ballistic flight begins, which can only be controlled using reactive forces.

At altitudes above 100 km, the atmosphere is also deprived of another remarkable property - the ability to absorb, conduct and transfer thermal energy by convection (that is, by mixing air). This means that various elements of equipment, equipment of the orbital space station they will not be able to be cooled from the outside in the way it is usually done on an airplane - with the help of air jets and air radiators. At such a height, as in space in general, the only way to transfer heat is thermal radiation.

History of the formation of the atmosphere

According to the most common theory, the Earth's atmosphere has been in three different compositions throughout its history. Initially, it consisted of light gases (hydrogen and helium) captured from interplanetary space. This so-called primary atmosphere. At the next stage, active volcanic activity led to the saturation of the atmosphere with gases other than hydrogen (carbon dioxide, ammonia, water vapor). This is how secondary atmosphere. This atmosphere was restorative. Further, the process of formation of the atmosphere was determined by the following factors:

- leakage of light gases (hydrogen and helium) into interplanetary space;

- chemical reactions occurring in the atmosphere under the influence of ultraviolet radiation, lightning discharges and some other factors.

Gradually, these factors led to the formation tertiary atmosphere, characterized by a much lower content of hydrogen and a much higher content of nitrogen and carbon dioxide (formed as a result of chemical reactions from ammonia and hydrocarbons).

Nitrogen

The formation of a large amount of nitrogen N 2 is due to the oxidation of the ammonia-hydrogen atmosphere by molecular oxygen O 2, which began to come from the surface of the planet as a result of photosynthesis, starting from 3 billion years ago. Nitrogen N 2 is also released into the atmosphere as a result of the denitrification of nitrates and other nitrogen-containing compounds. Nitrogen is oxidized by ozone to NO upper layers atmosphere.

Nitrogen N 2 enters into reactions only under specific conditions (for example, during a lightning discharge). Oxidation of molecular nitrogen by ozone during electrical discharges is used in small quantities in the industrial production of nitrogen fertilizers. Oxidize it with low energy consumption and convert it into biologically active form can be cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) and nodule bacteria that form a rhizobial symbiosis with legumes, which can be effective green manure plants that do not deplete, but enrich the soil with natural fertilizers.

Oxygen

The composition of the atmosphere began to change radically with the advent of living organisms on Earth, as a result of photosynthesis, accompanied by the release of oxygen and the absorption of carbon dioxide. Initially, oxygen was spent on the oxidation of reduced compounds - ammonia, hydrocarbons, the ferrous form of iron contained in the oceans, etc. At the end of this stage, the oxygen content in the atmosphere began to grow. Gradually, a modern atmosphere with oxidizing properties formed. Since this caused serious and abrupt changes in many processes occurring in the atmosphere, lithosphere and biosphere, this event was called the Oxygen catastrophe.

noble gases

Air pollution

Recently, man has begun to influence the evolution of the atmosphere. The result of human activity has been a constant increase in the content of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere due to the combustion of hydrocarbon fuels accumulated in previous geological epochs. Huge amounts of CO 2 are consumed during photosynthesis and absorbed by the world's oceans. This gas enters the atmosphere through the decomposition of carbonate rocks and organic matter of plant and animal origin, as well as due to volcanism and human production activities. Over the past 100 years, the content of CO 2 in the atmosphere has increased by 10%, with the main part (360 billion tons) coming from fuel combustion. If the growth rate of fuel combustion continues, then in the next 200-300 years the amount of CO 2 in the atmosphere will double and may lead to global climate change.

Fuel combustion is the main source of polluting gases (СО,, SO 2). Sulfur dioxide is oxidized by atmospheric oxygen to SO 3, and nitric oxide to NO 2 in the upper atmosphere, which in turn interact with water vapor, and the resulting sulfuric acid H 2 SO 4 and nitric acid HNO 3 fall on the Earth's surface in the form so-called. acid rain. The use of internal combustion engines leads to significant air pollution with nitrogen oxides, hydrocarbons and lead compounds (tetraethyl lead Pb (CH 3 CH 2) 4).

Aerosol pollution of the atmosphere is caused both by natural causes (volcanic eruption, dust storms, entrainment of sea water droplets and plant pollen, etc.) and by human economic activity (mining of ores and building materials, fuel combustion, cement production, etc.). Intensive large-scale removal of particulate matter into the atmosphere is one of the possible causes planetary climate change.

see also

- Jacchia (atmosphere model)

Write a review on the article "Atmosphere of the Earth"

Notes

- M. I. Budyko , K. Ya. Kondratiev Atmosphere of the Earth // Great Soviet Encyclopedia. 3rd ed. / Ch. ed. A. M. Prokhorov. - M .: Soviet Encyclopedia, 1970. - T. 2. Angola - Barzas. - pp. 380-384.

- - article from the Geological Encyclopedia

- Gribbin, John. Science. A History (1543-2001). - L. : Penguin Books, 2003. - 648 p. - ISBN 978-0-140-29741-6.

- Tans, Pieter. Globally averaged marine surface annual mean data . NOAA/ESRL. Retrieved February 19, 2014.(English) (for 2013)

- IPCC (English) (for 1998).

- S. P. Khromov Air humidity // Great Soviet Encyclopedia. 3rd ed. / Ch. ed. A. M. Prokhorov. - M .: Soviet Encyclopedia, 1971. - T. 5. Veshin - Gazli. - S. 149.

- (English) , SpaceDaily, 07/16/2010

Literature

- V. V. Parin, F. P. Kosmolinsky, B. A. Dushkov"Space biology and medicine" (2nd edition, revised and supplemented), M .: "Prosveshchenie", 1975, 223 pages.

- N. V. Gusakova"Chemistry environment", Rostov-on-Don: Phoenix, 2004, 192 with ISBN 5-222-05386-5

- Sokolov V. A. Geochemistry of natural gases, M., 1971;

- McEwen M, Phillips L. Chemistry of the atmosphere, M., 1978;

- Wark K., Warner S. Air pollution. Sources and control, trans. from English, M.. 1980;

- Background pollution monitoring natural environments. in. 1, L., 1982.

Links

- // December 17, 2013, FOBOS Center

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

An excerpt characterizing the Earth's atmosphere

When Pierre approached them, he noticed that Vera was in the self-satisfied enthusiasm of the conversation, Prince Andrei (which rarely happened to him) seemed embarrassed.- What do you think? Vera said with a thin smile. - You, prince, are so insightful and understand the character of people at once. What do you think of Natalie, can she be constant in her affections, can she, like other women (Vera understood herself), love a person once and remain faithful to him forever? This is what I consider true love. What do you think, prince?

“I know your sister too little,” answered Prince Andrei with a mocking smile, under which he wanted to hide his embarrassment, “to solve such a delicate question; and then I noticed that the less a woman likes, the more constant she is, ”he added and looked at Pierre, who had approached them at that time.

- Yes, it's true, prince; in our time, Vera continued (referring to our time, as limited people generally like to mention, believing that they have found and appreciated the features of our time and that the properties of people change with time), in our time the girl has so much freedom that le plaisir d "etre courtisee [the pleasure of having fans] often drowns out the true feeling in her. Et Nathalie, il faut l" avouer, y est tres sensible. [And Natalya, it must be confessed, is very sensitive to this.] The return to Natalya again made Prince Andrei frown unpleasantly; he wanted to get up, but Vera continued with an even more refined smile.

“I don’t think anyone was as courtisee [object of courtship] as she was,” Vera said; - but never, until very recently, did she seriously like anyone. You know, count, - she turned to Pierre, - even our dear cousin Boris, who was, entre nous [between us], very, very dans le pays du tendre ... [in the land of tenderness ...]

Prince Andrei frowned silently.

Are you friends with Boris? Vera told him.

- Yes, I know him…

- Did he tell you right about his childhood love for Natasha?

Was there childhood love? - suddenly suddenly blushing, asked Prince Andrei.

- Yes. Vous savez entre cousin et cousine cette intimate mene quelquefois a l "amour: le cousinage est un dangereux voisinage, N" est ce pas? [You know, between cousin and sister, this closeness sometimes leads to love. Such kinship is a dangerous neighborhood. Is not it?]

“Oh, without a doubt,” said Prince Andrei, and suddenly, unnaturally animated, he began to joke with Pierre about how careful he should be in his treatment of his 50-year-old Moscow cousins, and in the middle of a joking conversation, he got up and, taking under the arm of Pierre, took him aside.

- Well? - said Pierre, looking with surprise at the strange animation of his friend and noticing the look that he threw at Natasha getting up.

“I need, I need to talk to you,” said Prince Andrei. - You know our women's gloves (he talked about those Masonic gloves that were given to the newly elected brother to present to his beloved woman). - I ... But no, I'll talk to you later ... - And with a strange gleam in his eyes and restlessness in his movements, Prince Andrei went up to Natasha and sat down beside her. Pierre saw how Prince Andrei asked her something, and she, flushing, answered him.

But at this time, Berg approached Pierre, urging him to take part in a dispute between the general and the colonel about Spanish affairs.

Berg was pleased and happy. The smile of joy never left his face. The evening was very good and exactly like the other evenings he had seen. Everything was similar. And ladies' subtle conversations, and cards, and behind the cards the general raising his voice, and the samovar, and cookies; but one thing was still missing, that which he always saw at parties, which he wished to imitate.

There was a lack of loud conversation between men and an argument about something important and clever. The general started this conversation and Berg brought Pierre to it.

The next day, Prince Andrei went to the Rostovs for dinner, as Count Ilya Andreich called him, and spent the whole day with them.

Everyone in the house felt for whom Prince Andrei went, and he, without hiding, tried all day to be with Natasha. Not only in the soul of Natasha, frightened, but happy and enthusiastic, but in the whole house, fear was felt before something important that had to happen. The Countess looked at Prince Andrei with sad and seriously stern eyes when he spoke with Natasha, and timidly and feignedly began some kind of insignificant conversation, as soon as he looked back at her. Sonya was afraid to leave Natasha and was afraid to be a hindrance when she was with them. Natasha turned pale with fear of anticipation when she remained face to face with him for minutes. Prince Andrei struck her with his timidity. She felt that he needed to tell her something, but that he could not bring himself to do so.

When Prince Andrei left in the evening, the countess went up to Natasha and said in a whisper:

- Well?

- Mom, for God's sake don't ask me anything now. You can’t say that,” Natasha said.

But despite the fact that that evening Natasha, now agitated, now frightened, with stopping eyes, lay for a long time in her mother's bed. Now she told her how he praised her, then how he said that he would go abroad, then how he asked where they would live this summer, then how he asked her about Boris.

“But this, this… has never happened to me!” she said. “Only I’m scared around him, I’m always scared around him, what does that mean?” So it's real, right? Mom, are you sleeping?

“No, my soul, I myself am afraid,” answered the mother. - Go.

“I won’t sleep anyway. What's wrong with sleeping? Mommy, mommy, this has never happened to me! she said with astonishment and fear before the feeling that she was aware of in herself. - And could we think! ...

It seemed to Natasha that even when she first saw Prince Andrei in Otradnoye, she fell in love with him. She seemed to be frightened by this strange, unexpected happiness that the one whom she had chosen back then (she was firmly convinced of this), that the same one had now met her again, and, as it seems, was not indifferent to her. “And it was necessary for him, now that we are here, to come to Petersburg on purpose. And we should have met at this ball. All this is fate. It is clear that this is fate, that all this was led to this. Even then, as soon as I saw him, I felt something special.

What else did he tell you? What verses are these? Read it ... - thoughtfully said the mother, asking about the poems that Prince Andrei wrote in Natasha's album.

- Mom, is it not a shame that he is a widower?

- That's it, Natasha. Pray to God. Les Marieiages se font dans les cieux. [Marriages are made in heaven.]

“Darling, mother, how I love you, how good it is for me!” Natasha shouted, crying tears of happiness and excitement and hugging her mother.

At the same time, Prince Andrei was sitting with Pierre and telling him about his love for Natasha and about his firm intention to marry her.

On that day, Countess Elena Vasilievna had a reception, there was a French envoy, there was a prince, who had recently become a frequent visitor to the countess's house, and many brilliant ladies and men. Pierre was downstairs, walked through the halls, and struck all the guests with his concentrated, absent-minded and gloomy look.

From the time of the ball, Pierre felt the approach of fits of hypochondria in himself and with a desperate effort tried to fight against them. From the time of the prince’s rapprochement with his wife, Pierre was unexpectedly granted a chamberlain, and from that time on he began to feel heaviness and shame in a large society, and more often the same gloomy thoughts about the futility of everything human began to come to him. At the same time, the feeling he noticed between Natasha, who was patronized by him, and Prince Andrei, his opposition between his position and the position of his friend, further strengthened this gloomy mood. He equally tried to avoid thoughts about his wife and about Natasha and Prince Andrei. Again everything seemed to him insignificant in comparison with eternity, again the question presented itself: “what for?”. And he forced himself day and night to work on the Masonic works, hoping to drive away the approach of the evil spirit. Pierre at 12 o'clock, leaving the countess's chambers, was sitting upstairs in a smoky, low room, in a worn dressing gown in front of the table and copying genuine Scottish acts, when someone entered his room. It was Prince Andrew.

“Ah, it’s you,” said Pierre with an absent-minded and displeased look. “But I’m working,” he said, pointing to a notebook with that kind of salvation from the hardships of life with which unhappy people look at their work.

Prince Andrei, with a beaming, enthusiastic face, renewed to life, stopped in front of Pierre and, not noticing his sad face, smiled at him with egoism of happiness.

“Well, my soul,” he said, “yesterday I wanted to tell you and today I came to you for this. Never experienced anything like it. I'm in love my friend.

Pierre suddenly sighed heavily and sank down with his heavy body on the sofa, next to Prince Andrei.

- To Natasha Rostov, right? - he said.

- Yes, yes, in whom? I would never believe it, but this feeling is stronger than me. Yesterday I suffered, suffered, but I will not give up this torment for anything in the world. I haven't lived before. Now only I live, but I can't live without her. But can she love me?... I'm old for her... What don't you say?...

- I? I? What did I tell you, - Pierre suddenly said, getting up and starting to walk around the room. - I always thought this ... This girl is such a treasure, such ... This is a rare girl ... Dear friend, I ask you, do not think, do not hesitate, marry, marry and marry ... And I am sure that no one will be happier than you.

- But she!

- She loves you.

“Don’t talk nonsense ...” said Prince Andrei, smiling and looking into Pierre’s eyes.

“He loves, I know,” Pierre shouted angrily.

“No, listen,” said Prince Andrei, stopping him by the hand. Do you know what position I'm in? I need to tell everything to someone.

“Well, well, say, I’m very glad,” Pierre said, and indeed his face changed, the wrinkle smoothed out, and he joyfully listened to Prince Andrei. Prince Andrei seemed and was a completely different, new person. Where was his anguish, his contempt for life, his disappointment? Pierre was the only person before whom he dared to speak out; but on the other hand, he told him everything that was in his soul. Either he easily and boldly made plans for a long future, talked about how he could not sacrifice his happiness for the whim of his father, how he would force his father to agree to this marriage and love her or do without his consent, then he was surprised how on something strange, alien, independent of him, against the feeling that possessed him.

“I would not believe someone who would tell me that I can love like that,” said Prince Andrei. “It's not the same feeling I had before. The whole world is divided for me into two halves: one is she and there is all the happiness of hope, light; the other half - everything where it is not there, there is all despondency and darkness ...

“Darkness and gloom,” Pierre repeated, “yes, yes, I understand that.

“I can't help but love the light, it's not my fault. And I am very happy. You understand me? I know that you are happy for me.

“Yes, yes,” Pierre confirmed, looking at his friend with touching and sad eyes. The brighter the fate of Prince Andrei seemed to him, the darker his own seemed.

For marriage, the consent of the father was needed, and for this, the next day, Prince Andrei went to his father.

The father, with outward calm, but inward malice, received his son's message. He could not understand that someone wanted to change life, to bring something new into it, when life was already ending for him. “They would only let me live the way I want, and then they would do what they wanted,” the old man said to himself. With his son, however, he used the diplomacy he used on important occasions. Assuming a calm tone, he discussed the whole matter.

Firstly, the marriage was not brilliant in relation to kinship, wealth and nobility. Secondly, Prince Andrei was not the first youth and was in poor health (the old man especially leaned on this), and she was very young. Thirdly, there was a son whom it was a pity to give to a girl. Fourthly, finally, - said the father, looking mockingly at his son, - I ask you, put the matter aside for a year, go abroad, take medical treatment, find, as you like, a German, for Prince Nikolai, and then, if it’s love, passion, stubbornness, whatever you want, so great, then get married.

“And this is my last word, you know, the last ...” the prince finished in such a tone that he showed that nothing would make him change his mind.

Prince Andrei clearly saw that the old man hoped that the feeling of his or his future bride would not stand the test of the year, or that he himself, old prince, will die by this time, and decided to fulfill the will of his father: to propose and postpone the wedding for a year.

Three weeks after his last evening at the Rostovs, Prince Andrei returned to Petersburg.

The next day after her explanation with her mother, Natasha waited all day for Bolkonsky, but he did not arrive. The next day, the third day, it was the same. Pierre also did not come, and Natasha, not knowing that Prince Andrei had gone to her father, could not explain his absence to herself.

So three weeks passed. Natasha did not want to go anywhere, and like a shadow, idle and despondent, she walked around the rooms, in the evening she secretly cried from everyone and did not appear in the evenings to her mother. She was constantly blushing and irritated. It seemed to her that everyone knew about her disappointment, laughed and regretted her. With all the strength of inner grief, this vainglorious grief increased her misfortune.

One day she came to the countess, wanted to say something to her, and suddenly burst into tears. Her tears were the tears of an offended child who himself does not know why he is being punished.

The Countess began to reassure Natasha. Natasha, who at first listened to her mother's words, suddenly interrupted her:

- Stop it, mom, I don’t think, and I don’t want to think! So, I traveled and stopped, and stopped ...

Her voice trembled, she almost burst into tears, but she recovered herself and calmly continued: “And I don’t want to get married at all. And I'm afraid of him; I am now completely, completely, calmed down ...

The next day after this conversation, Natasha put on that old dress, which she was especially aware of for the cheerfulness it delivered in the morning, and in the morning she began her former way of life, from which she lagged behind after the ball. After drinking tea, she went to the hall, which she especially loved for its strong resonance, and began to sing her solfeji (singing exercises). Having finished the first lesson, she stopped in the middle of the hall and repeated one musical phrase that she especially liked. She listened joyfully to that (as if unexpected for her) charm with which these sounds, shimmering, filled the entire emptiness of the hall and slowly died away, and she suddenly became cheerful. “Why think about it so much and so well,” she said to herself, and began to walk up and down the hall, stepping not with simple steps on the resonant parquet, but at every step stepping from heel (she was wearing new, favorite shoes) to toe, and just as joyfully as to the sounds of his voice, listening to this measured clatter of heels and the creaking of socks. Passing by a mirror, she looked into it. - "Here I am!" as if the expression on her face at the sight of herself spoke. “Well, that's good. And I don't need anyone."

The footman wanted to come in to clean up something in the hall, but she did not let him in, again shutting the door behind him, and continued her walk. She returned that morning again to her beloved state of self-love and admiration for herself. - “What a charm this Natasha is!” she said again to herself in the words of some third, collective, masculine face. - "Good, voice, young, and she does not interfere with anyone, just leave her alone." But no matter how much they left her alone, she could no longer be at peace, and immediately felt it.

In the front door the entrance door opened, someone asked: are you at home? and someone's footsteps were heard. Natasha looked in the mirror, but she did not see herself. She listened to the sounds in the hallway. When she saw herself, her face was pale. It was he. She knew this for sure, although she barely heard the sound of his voice from the closed doors.

Natasha, pale and frightened, ran into the living room.

- Mom, Bolkonsky has arrived! - she said. - Mom, this is terrible, this is unbearable! “I don’t want to… suffer!” What should I do?…

The countess had not yet had time to answer her, when Prince Andrei entered the drawing room with an anxious and serious face. As soon as he saw Natasha, his face lit up. He kissed the hand of the countess and Natasha and sat down beside the sofa.

“For a long time we have not had pleasure ...” the countess began, but Prince Andrei interrupted her, answering her question and obviously in a hurry to say what he needed.

- I have not been with you all this time, because I was with my father: I needed to talk to him about a very important matter. I just got back last night,” he said, looking at Natasha. “I need to talk to you, Countess,” he added after a moment's silence.

The Countess sighed heavily and lowered her eyes.

“I am at your service,” she said.

Natasha knew that she had to leave, but she could not do it: something was squeezing her throat, and she looked impolitely, directly, with open eyes at Prince Andrei.

"Now? This minute!… No, it can't be!” she thought.

He looked at her again, and this look convinced her that she had not been mistaken. - Yes, now, this very minute her fate was being decided.

“Come, Natasha, I will call you,” said the countess in a whisper.

Natasha looked with frightened, pleading eyes at Prince Andrei and at her mother, and went out.

“I have come, Countess, to ask for the hand of your daughter,” said Prince Andrei. The countess's face flushed, but she said nothing.

“Your suggestion…” the Countess began sedately. He remained silent, looking into her eyes. - Your offer ... (she was embarrassed) we are pleased, and ... I accept your offer, I'm glad. And my husband ... I hope ... but it will depend on her ...

- I will tell her when I have your consent ... do you give it to me? - said Prince Andrew.

“Yes,” said the Countess, and held out her hand to him, and with a mixture of aloofness and tenderness pressed her lips to his forehead as he leaned over her hand. She wanted to love him like a son; but she felt that he was a stranger and a terrible person for her. “I'm sure my husband will agree,” said the countess, “but your father ...

- My father, to whom I informed my plans, made it an indispensable condition for consent that the wedding should not be before a year. And this is what I wanted to tell you, - said Prince Andrei.

- It is true that Natasha is still young, but so long.

“It could not be otherwise,” Prince Andrei said with a sigh.

“I will send it to you,” said the countess, and left the room.

“Lord, have mercy on us,” she repeated, looking for her daughter. Sonya said that Natasha was in the bedroom. Natasha sat on her bed, pale, with dry eyes, looked at the icons and, quickly making the sign of the cross, whispered something. Seeing her mother, she jumped up and rushed to her.

- What? Mom?… What?

- Go, go to him. He asks for your hand, - said the countess coldly, as it seemed to Natasha ... - Go ... go, - the mother said with sadness and reproach after her daughter, who was running away, and sighed heavily.

Natasha did not remember how she entered the living room. When she entered the door and saw him, she stopped. “Is this stranger really become my everything now?” she asked herself and instantly answered: “Yes, everything: he alone is now dearer to me than everything in the world.” Prince Andrei went up to her, lowering his eyes.

“I fell in love with you from the moment I saw you. Can I hope?

He looked at her, and the earnest passion of her countenance struck him. Her face said: “Why ask? Why doubt that which is impossible not to know? Why talk when you can’t express what you feel in words.

She approached him and stopped. He took her hand and kissed it.

– Do you love me?

“Yes, yes,” Natasha said as if with annoyance, sighed loudly, another time, more and more often, and sobbed.

– About what? What's wrong with you?

“Oh, I’m so happy,” she answered, smiled through her tears, leaned closer to him, thought for a second, as if asking herself if it was possible, and kissed him.

Prince Andrei held her hands, looked into her eyes, and did not find in his soul the former love for her. Something suddenly turned in his soul: there was no former poetic and mysterious charm of desire, but there was pity for her feminine and childish weakness, there was fear of her devotion and gullibility, a heavy and at the same time joyful consciousness of the duty that forever connected him with her. The real feeling, although it was not as light and poetic as the former, was more serious and stronger.

The atmosphere is the air envelope of the Earth. Extending up to 3000 km from the earth's surface. Its traces can be traced to a height of up to 10,000 km. A. has an uneven density of 50 5; its masses are concentrated up to 5 km, 75% - up to 10 km, 90% - up to 16 km.

The atmosphere consists of air - a mechanical mixture of several gases.

Nitrogen(78%) in the atmosphere plays the role of an oxygen diluent, regulating the rate of oxidation, and, consequently, the rate and intensity biological processes. Nitrogen is the main element earth's atmosphere, which continuously exchanges with the living matter of the biosphere, and constituent parts the latter are nitrogen compounds (amino acids, purines, etc.). Extraction of nitrogen from the atmosphere occurs inorganic and biochemical ways, although they are closely interrelated. Inorganic extraction is associated with the formation of its compounds N 2 O, N 2 O 5 , NO 2 , NH 3 . They are found in precipitation and are formed in the atmosphere under the action of electrical discharges during thunderstorms or photochemical reactions under the influence of solar radiation.

Biological nitrogen fixation is carried out by some bacteria in symbiosis with higher plants in soils. Nitrogen is also fixed by some plankton microorganisms and algae in the marine environment. In quantitative terms, the biological binding of nitrogen exceeds its inorganic fixation. The exchange of all the nitrogen in the atmosphere takes approximately 10 million years. Nitrogen is found in gases of volcanic origin and in igneous rocks. When various samples of crystalline rocks and meteorites are heated, nitrogen is released in the form of N 2 and NH 3 molecules. However, the main form of nitrogen presence, both on Earth and on the terrestrial planets, is molecular. Ammonia, getting into the upper atmosphere, is rapidly oxidized, releasing nitrogen. In sedimentary rocks, it is buried together with organic matter and is found in an increased amount in bituminous deposits. In the process of regional metamorphism of these rocks, nitrogen in various forms is released into the Earth's atmosphere.

Geochemical nitrogen cycle (

Oxygen(21%) is used by living organisms for respiration, is part of organic matter (proteins, fats, carbohydrates). Ozone O 3 . blocking life-threatening ultraviolet radiation from the Sun.

Oxygen is the second most abundant atmospheric gas, playing exclusively important role in many processes of the biosphere. The dominant form of its existence is O 2 . In the upper layers of the atmosphere, under the influence of ultraviolet radiation, oxygen molecules dissociate, and at an altitude of about 200 km, the ratio of atomic oxygen to molecular (O: O 2) becomes equal to 10. When these forms of oxygen interact in the atmosphere (at an altitude of 20-30 km), ozone belt (ozone shield). Ozone (O 3) is necessary for living organisms, delaying most of the solar ultraviolet radiation that is harmful to them.

In the early stages of the Earth's development, free oxygen arose in very small quantities as a result of the photodissociation of carbon dioxide and water molecules in the upper atmosphere. However, these small amounts were quickly consumed in the oxidation of other gases. With the advent of autotrophic photosynthetic organisms in the ocean, the situation has changed significantly. The amount of free oxygen in the atmosphere began to progressively increase, actively oxidizing many components of the biosphere. Thus, the first portions of free oxygen contributed primarily to the transition of ferrous forms of iron into oxide, and sulfides into sulfates.

In the end, the amount of free oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere reached a certain mass and turned out to be balanced in such a way that the amount produced became equal to the amount absorbed. A relative constancy of the content of free oxygen was established in the atmosphere.

Geochemical oxygen cycle (V.A. Vronsky, G.V. Voitkevich)

Carbon dioxide, goes to the formation of living matter, and together with water vapor creates the so-called "greenhouse (greenhouse) effect."

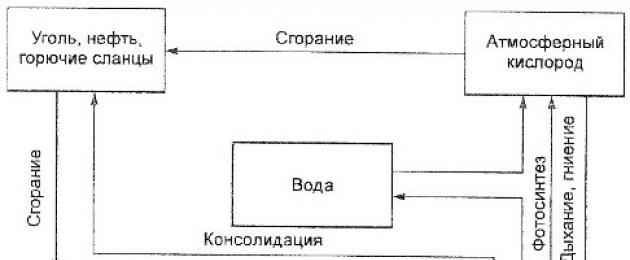

Carbon (carbon dioxide) - most of it in the atmosphere is in the form of CO 2 and much less in the form of CH 4. The significance of the geochemical history of carbon in the biosphere is exceptionally great, since it is a part of all living organisms. Within living organisms, reduced forms of carbon are predominant, and in the environment of the biosphere, oxidized ones. Thus, a chemical exchange is established life cycle: CO 2 ↔ living matter.

The primary source of carbon dioxide in the biosphere is volcanic activity associated with secular degassing of the mantle and lower horizons of the earth's crust. Part of this carbon dioxide arises from the thermal decomposition of ancient limestones in various metamorphic zones. Migration of CO 2 in the biosphere proceeds in two ways.

The first method is expressed in the absorption of CO 2 in the process of photosynthesis with the formation of organic substances and subsequent burial in favorable reducing conditions in the lithosphere in the form of peat, coal, oil, oil shale. According to the second method, carbon migration leads to the creation of a carbonate system in the hydrosphere, where CO 2 turns into H 2 CO 3, HCO 3 -1, CO 3 -2. Then, with the participation of calcium (less often magnesium and iron), the precipitation of carbonates occurs in a biogenic and abiogenic way. Thick strata of limestones and dolomites appear. According to A.B. Ronov, the ratio of organic carbon (Corg) to carbonate carbon (Ccarb) in the history of the biosphere was 1:4.

Along with the global cycle of carbon, there are a number of its small cycles. So, on land, green plants absorb CO 2 for the process of photosynthesis during the daytime, and at night they release it into the atmosphere. With the death of living organisms on the earth's surface, organic matter is oxidized (with the participation of microorganisms) with the release of CO 2 into the atmosphere. In recent decades, a special place in the carbon cycle has been occupied by the massive combustion of fossil fuels and the increase in its content in the modern atmosphere.

The carbon cycle in geographical envelope(according to F. Ramad, 1981)

Argon- the third most common atmospheric gas, which sharply distinguishes it from the extremely scarcely common other inert gases. However, argon in its geological history shares the fate of these gases, which are characterized by two features:

- the irreversibility of their accumulation in the atmosphere;

- close association with the radioactive decay of certain unstable isotopes.

Inert gases are outside the circulation of most cyclic elements in the Earth's biosphere.

All inert gases can be divided into primary and radiogenic. The primary ones are those that were captured by the Earth during its formation. They are extremely rare. The primary part of argon is represented mainly by 36 Ar and 38 Ar isotopes, while atmospheric argon consists entirely of the 40 Ar isotope (99.6%), which is undoubtedly radiogenic. In potassium-containing rocks, radiogenic argon accumulated due to the decay of potassium-40 by electron capture: 40 K + e → 40 Ar.

Therefore, the content of argon in rocks is determined by their age and the amount of potassium. To this extent, the concentration of helium in rocks is a function of their age and the content of thorium and uranium. Argon and helium are released into the atmosphere from the earth's interior during volcanic eruptions, through cracks in the earth's crust in the form of gas jets, and also during the weathering of rocks. According to the calculations performed by P. Dimon and J. Culp, helium and argon in modern era accumulate in the earth's crust and enter the atmosphere in relatively small quantities. The rate of entry of these radiogenic gases is so low that during the geological history of the Earth it could not provide the observed content of them in the modern atmosphere. Therefore, it remains to be assumed that most of the argon in the atmosphere came from the bowels of the Earth at the earliest stages of its development, and a much smaller part was added later in the process of volcanism and during the weathering of potassium-containing rocks.

Thus, during geological time, helium and argon had different migration processes. There is very little helium in the atmosphere (about 5 * 10 -4%), and the "helium breath" of the Earth was lighter, since it, as the lightest gas, escaped into outer space. And "argon breath" - heavy and argon remained within our planet. Most of of primary inert gases, like neon and xenon, was associated with primary neon captured by the Earth during its formation, as well as with the release into the atmosphere during degassing of the mantle. The totality of data on the geochemistry of noble gases indicates that the primary atmosphere of the Earth arose at the earliest stages of its development.

The atmosphere contains water vapor And water in liquid and solid state. Water in the atmosphere is an important heat accumulator.

The lower layers of the atmosphere contain a large amount of mineral and technogenic dust and aerosols, combustion products, salts, spores and plant pollen, etc.

Up to a height of 100-120 km, due to the complete mixing of air, the composition of the atmosphere is homogeneous. The ratio between nitrogen and oxygen is constant. Above, inert gases, hydrogen, etc. predominate. In the lower layers of the atmosphere there is water vapor. With distance from the earth, its content decreases. Above, the ratio of gases changes, for example, at an altitude of 200-800 km, oxygen prevails over nitrogen by 10-100 times.

Atmosphere (from other Greek ἀτμός - steam and σφαῖρα - ball) is a gaseous shell (geosphere) surrounding the planet Earth. Its inner surface covers the hydrosphere and partially the earth's crust, the outer one borders on the near-Earth part of outer space.

The totality of sections of physics and chemistry that study the atmosphere is commonly called atmospheric physics. The atmosphere determines the weather on the surface of the Earth, meteorology is the study of weather, and climatology is the study of long-term climate variations.

Physical properties

The thickness of the atmosphere is about 120 km from the Earth's surface. The total mass of air in the atmosphere is (5.1-5.3) 1018 kg. Of these, the mass of dry air is (5.1352 ± 0.0003) 1018 kg, the total mass of water vapor is on average 1.27 1016 kg.

The molar mass of clean dry air is 28.966 g/mol, the air density near the sea surface is approximately 1.2 kg/m3. The pressure at 0 °C at sea level is 101.325 kPa; critical temperature - -140.7 ° C (~ 132.4 K); critical pressure - 3.7 MPa; Cp at 0 °C - 1.0048 103 J/(kg K), Cv - 0.7159 103 J/(kg K) (at 0 °C). The solubility of air in water (by mass) at 0 ° C - 0.0036%, at 25 ° C - 0.0023%.

For "normal conditions" at the Earth's surface are taken: density 1.2 kg/m3, barometric pressure 101.35 kPa, temperature plus 20 °C and relative humidity 50%. These conditional indicators have a purely engineering value.

Chemical composition

The Earth's atmosphere arose as a result of the release of gases during volcanic eruptions. With the advent of the oceans and the biosphere, it was also formed due to gas exchange with water, plants, animals and their decomposition products in soils and swamps.

At present, the Earth's atmosphere consists mainly of gases and various impurities (dust, water drops, ice crystals, sea salts, combustion products).

The concentration of gases that make up the atmosphere is almost constant, with the exception of water (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2).

Composition of dry air

| Nitrogen | ||

| Oxygen | ||

| Argon | ||

| Water | ||

| Carbon dioxide | ||

| Neon | ||

| Helium | ||

| Methane | ||

| Krypton | ||

| Hydrogen | ||

| Xenon | ||

| Nitrous oxide |

In addition to the gases indicated in the table, the atmosphere contains SO2, NH3, CO, ozone, hydrocarbons, HCl, HF, Hg vapor, I2, as well as NO and many other gases in small quantities. In the troposphere there is constantly a large amount of suspended solid and liquid particles (aerosol).

The structure of the atmosphere

Troposphere

Its upper limit is at an altitude of 8-10 km in polar, 10-12 km in temperate and 16-18 km in tropical latitudes; lower in winter than in summer. The lower, main layer of the atmosphere contains more than 80% of the total mass of atmospheric air and about 90% of all water vapor present in the atmosphere. In the troposphere, turbulence and convection are highly developed, clouds appear, cyclones and anticyclones develop. Temperature decreases with altitude with an average vertical gradient of 0.65°/100 m

tropopause

The transitional layer from the troposphere to the stratosphere, the layer of the atmosphere in which the decrease in temperature with height stops.

Stratosphere

The layer of the atmosphere located at an altitude of 11 to 50 km. A slight change in temperature in the 11-25 km layer (the lower layer of the stratosphere) and its increase in the 25-40 km layer from −56.5 to 0.8 °C (upper stratosphere layer or inversion region) are typical. Having reached a value of about 273 K (almost 0 °C) at an altitude of about 40 km, the temperature remains constant up to an altitude of about 55 km. This region of constant temperature is called the stratopause and is the boundary between the stratosphere and the mesosphere.

Stratopause

The boundary layer of the atmosphere between the stratosphere and the mesosphere. There is a maximum in the vertical temperature distribution (about 0 °C).

Mesosphere

The mesosphere begins at an altitude of 50 km and extends up to 80-90 km. The temperature decreases with height with an average vertical gradient of (0.25-0.3)°/100 m. The main energy process is radiant heat transfer. Complex photochemical processes involving free radicals, vibrationally excited molecules, etc., cause atmospheric luminescence.

mesopause

Transitional layer between mesosphere and thermosphere. There is a minimum in the vertical temperature distribution (about -90 °C).

Karman Line

Altitude above sea level, which is conventionally accepted as the boundary between the Earth's atmosphere and space. According to the FAI definition, the Karman Line is at an altitude of 100 km above sea level.

Earth's atmosphere boundary

Thermosphere

The upper limit is about 800 km. The temperature rises to altitudes of 200-300 km, where it reaches values of the order of 1500 K, after which it remains almost constant up to high altitudes. Under the influence of ultraviolet and x-ray solar radiation and cosmic radiation, air is ionized (“polar lights”) - the main regions of the ionosphere lie inside the thermosphere. At altitudes above 300 km, atomic oxygen predominates. The upper limit of the thermosphere is largely determined by the current activity of the Sun. During periods of low activity - for example, in 2008-2009 - there is a noticeable decrease in the size of this layer.

Thermopause

The region of the atmosphere above the thermosphere. In this region, the absorption of solar radiation is insignificant and the temperature does not actually change with height.

Exosphere (scattering sphere)

Exosphere - scattering zone, the outer part of the thermosphere, located above 700 km. The gas in the exosphere is highly rarefied, and hence its particles leak into interplanetary space (dissipation).

Up to a height of 100 km, the atmosphere is a homogeneous, well-mixed mixture of gases. In higher layers, the distribution of gases in height depends on their molecular masses, the concentration of heavier gases decreases faster with distance from the Earth's surface. Due to the decrease in gas density, the temperature drops from 0 °C in the stratosphere to −110 °C in the mesosphere. However, the kinetic energy of individual particles at altitudes of 200–250 km corresponds to a temperature of ~150 °C. Above 200 km, significant fluctuations in temperature and gas density are observed in time and space.

At an altitude of about 2000-3500 km, the exosphere gradually passes into the so-called near space vacuum, which is filled with highly rarefied particles of interplanetary gas, mainly hydrogen atoms. But this gas is only part of the interplanetary matter. The other part is composed of dust-like particles of cometary and meteoric origin. In addition to extremely rarefied dust-like particles, electromagnetic and corpuscular radiation of solar and galactic origin penetrates into this space.

The troposphere accounts for about 80% of the mass of the atmosphere, the stratosphere accounts for about 20%; the mass of the mesosphere is no more than 0.3%, the thermosphere is less than 0.05% of the total mass of the atmosphere. Based on the electrical properties in the atmosphere, the neutrosphere and ionosphere are distinguished. It is currently believed that the atmosphere extends to an altitude of 2000-3000 km.

Depending on the composition of the gas in the atmosphere, homosphere and heterosphere are distinguished. The heterosphere is an area where gravity has an effect on the separation of gases, since their mixing at such a height is negligible. Hence follows the variable composition of the heterosphere. Below it lies a well-mixed, homogeneous part of the atmosphere, called the homosphere. The boundary between these layers is called the turbopause and lies at an altitude of about 120 km.

Other properties of the atmosphere and effects on the human body

Already at an altitude of 5 km above sea level, an untrained person develops oxygen starvation and, without adaptation, a person's performance is significantly reduced. This is where the physiological zone of the atmosphere ends. Human breathing becomes impossible at an altitude of 9 km, although up to about 115 km the atmosphere contains oxygen.

The atmosphere provides us with the oxygen we need to breathe. However, due to the drop in the total pressure of the atmosphere as you rise to a height, the partial pressure of oxygen also decreases accordingly.

The human lungs constantly contain about 3 liters of alveolar air. The partial pressure of oxygen in the alveolar air at normal atmospheric pressure is 110 mm Hg. Art., pressure of carbon dioxide - 40 mm Hg. Art., and water vapor - 47 mm Hg. Art. With increasing altitude, the oxygen pressure drops, and the total pressure of water vapor and carbon dioxide in the lungs remains almost constant - about 87 mm Hg. Art. The flow of oxygen into the lungs will completely stop when the pressure of the surrounding air becomes equal to this value.

At an altitude of about 19-20 km, the atmospheric pressure drops to 47 mm Hg. Art. Therefore, at this height, water and interstitial fluid begin to boil in the human body. Outside the pressurized cabin at these altitudes, death occurs almost instantly. Thus, from the point of view of human physiology, "space" begins already at an altitude of 15-19 km.

Dense layers of air - the troposphere and stratosphere - protect us from the damaging effects of radiation. With sufficient rarefaction of air, at altitudes of more than 36 km, ionizing radiation has an intense effect on the body - primary cosmic rays; at altitudes of more than 40 km, the ultraviolet part of the solar spectrum, which is dangerous for humans, operates.

As we rise to an ever greater height above the Earth's surface, such phenomena that are familiar to us observed in the lower layers of the atmosphere, such as the propagation of sound, the occurrence of aerodynamic lift and drag, heat transfer by convection, etc., gradually weaken, and then completely disappear.

In rarefied layers of air, the propagation of sound is impossible. Up to altitudes of 60-90 km, it is still possible to use air resistance and lift for controlled aerodynamic flight. But starting from altitudes of 100-130 km, the concepts of the M number and the sound barrier familiar to every pilot lose their meaning: there is a conditional Karman line, beyond which begins the area of purely ballistic flight, which can only be controlled using reactive forces.

At altitudes above 100 km, the atmosphere is also deprived of another remarkable property - the ability to absorb, conduct and transfer thermal energy by convection (i.e., by means of air mixing). This means that various elements of equipment, equipment of the orbital space station will not be able to be cooled from the outside in the way it is usually done on an airplane - with the help of air jets and air radiators. At this altitude, as well as in space in general, the only way to transfer heat is thermal radiation.

History of the formation of the atmosphere

According to the most common theory, the Earth's atmosphere has been in three different compositions over time. Initially, it consisted of light gases (hydrogen and helium) captured from interplanetary space. This is the so-called primary atmosphere (about four billion years ago). At the next stage, active volcanic activity led to the saturation of the atmosphere with gases other than hydrogen (carbon dioxide, ammonia, water vapor). This is how the secondary atmosphere was formed (about three billion years to the present day). This atmosphere was restorative. Further, the process of formation of the atmosphere was determined by the following factors:

- leakage of light gases (hydrogen and helium) into interplanetary space;

- chemical reactions occurring in the atmosphere under the influence of ultraviolet radiation, lightning discharges and some other factors.

Gradually, these factors led to the formation of a tertiary atmosphere, characterized by a much lower content of hydrogen and a much higher content of nitrogen and carbon dioxide (formed as a result of chemical reactions from ammonia and hydrocarbons).

Nitrogen

The formation of a large amount of nitrogen N2 is due to the oxidation of the ammonia-hydrogen atmosphere by molecular oxygen O2, which began to come from the surface of the planet as a result of photosynthesis, starting from 3 billion years ago. Nitrogen N2 is also released into the atmosphere as a result of the denitrification of nitrates and other nitrogen-containing compounds. Nitrogen is oxidized by ozone to NO in the upper atmosphere.

Nitrogen N2 enters into reactions only under specific conditions (for example, during a lightning discharge). Oxidation of molecular nitrogen by ozone during electrical discharges is used in small quantities in the industrial production of nitrogen fertilizers. It can be oxidized with low energy consumption and converted into a biologically active form by cyanobacteria ( blue-green algae) and nodule bacteria that form a rhizobial symbiosis with leguminous plants, the so-called. green manure.

Oxygen

The composition of the atmosphere began to change radically with the advent of living organisms on Earth, as a result of photosynthesis, accompanied by the release of oxygen and the absorption of carbon dioxide. Initially, oxygen was spent on the oxidation of reduced compounds - ammonia, hydrocarbons, the ferrous form of iron contained in the oceans, etc. At the end of this stage, the oxygen content in the atmosphere began to grow. Gradually, a modern atmosphere with oxidizing properties formed. Since this caused serious and abrupt changes in many processes occurring in the atmosphere, lithosphere and biosphere, this event was called the Oxygen Catastrophe.

During the Phanerozoic, the composition of the atmosphere and the oxygen content underwent changes. They correlated primarily with the rate of deposition of organic sedimentary rocks. So, during the periods of coal accumulation, the oxygen content in the atmosphere, apparently, noticeably exceeded the modern level.

Carbon dioxide

The content of CO2 in the atmosphere depends on volcanic activity and chemical processes in the earth's shells, but most of all - on the intensity of biosynthesis and decomposition of organic matter in the Earth's biosphere. Almost the entire current biomass of the planet (about 2.4 1012 tons) is formed due to carbon dioxide, nitrogen and water vapor contained in the atmospheric air. Buried in the ocean, in swamps and in forests, organic matter turns into coal, oil and natural gas.

noble gases

The source of inert gases - argon, helium and krypton - is volcanic eruptions and the decay of radioactive elements. The earth as a whole and the atmosphere in particular are depleted in inert gases compared to space. It is believed that the reason for this lies in the continuous leakage of gases into interplanetary space.

Air pollution

Recently, man has begun to influence the evolution of the atmosphere. The result of his activities was a constant increase in the content of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere due to the combustion of hydrocarbon fuels accumulated in previous geological epochs. Huge amounts of CO2 are consumed during photosynthesis and absorbed by the world's oceans. This gas enters the atmosphere due to the decomposition of carbonate rocks and organic substances of plant and animal origin, as well as due to volcanism and human production activities. Over the past 100 years, the content of CO2 in the atmosphere has increased by 10%, with the main part (360 billion tons) coming from fuel combustion. If the growth rate of fuel combustion continues, then in the next 200-300 years the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere will double and may lead to global climate change.

Fuel combustion is the main source of polluting gases (CO, NO, SO2). Sulfur dioxide is oxidized by atmospheric oxygen to SO3, and nitric oxide to NO2 in the upper atmosphere, which in turn interact with water vapor, and the resulting sulfuric acid H2SO4 and nitric acid HNO3 fall to the Earth's surface in the form of the so-called. acid rain. The use of internal combustion engines leads to significant air pollution with nitrogen oxides, hydrocarbons and lead compounds (tetraethyl lead) Pb(CH3CH2)4.

Aerosol pollution of the atmosphere is caused both by natural causes (volcanic eruption, dust storms, entrainment of sea water droplets and plant pollen, etc.) and by human economic activity (mining of ores and building materials, fuel combustion, cement production, etc.). Intense large-scale removal of solid particles into the atmosphere is one of the possible causes of climate change on the planet.

(Visited 730 times, 1 visits today)

Its upper limit is at an altitude of 8-10 km in polar, 10-12 km in temperate and 16-18 km in tropical latitudes; lower in winter than in summer. The lower, main layer of the atmosphere. It contains more than 80% of the total mass of atmospheric air and about 90% of all water vapor present in the atmosphere. Turbulence and convection are strongly developed in the troposphere, clouds appear, cyclones and anticyclones develop. Temperature decreases with altitude with an average vertical gradient of 0.65°/100 m

For "normal conditions" at the Earth's surface are taken: density 1.2 kg/m3, barometric pressure 101.35 kPa, temperature plus 20 °C and relative humidity 50%. These conditional indicators have a purely engineering value.

Stratosphere

The layer of the atmosphere located at an altitude of 11 to 50 km. A slight change in temperature in the 11-25 km layer (lower layer of the stratosphere) and its increase in the 25-40 km layer from −56.5 to 0.8 ° (upper stratosphere or inversion region) are typical. Having reached a value of about 273 K (almost 0 ° C) at an altitude of about 40 km, the temperature remains constant up to an altitude of about 55 km. This region of constant temperature is called the stratopause and is the boundary between the stratosphere and the mesosphere.

Stratopause

The boundary layer of the atmosphere between the stratosphere and the mesosphere. There is a maximum in the vertical temperature distribution (about 0 °C).

Mesosphere

mesopause

Transitional layer between mesosphere and thermosphere. There is a minimum in the vertical temperature distribution (about -90°C).

Karman Line

Altitude above sea level, which is conventionally accepted as the boundary between the Earth's atmosphere and space.

Thermosphere

The upper limit is about 800 km. The temperature rises to altitudes of 200-300 km, where it reaches values of the order of 1500 K, after which it remains almost constant up to high altitudes. Under the influence of ultraviolet and x-ray solar radiation and cosmic radiation, air is ionized ("polar lights") - the main regions of the ionosphere lie inside the thermosphere. At altitudes above 300 km, atomic oxygen predominates.

Exosphere (scattering sphere)

Up to a height of 100 km, the atmosphere is a homogeneous, well-mixed mixture of gases. In higher layers, the distribution of gases in height depends on their molecular masses, the concentration of heavier gases decreases faster with distance from the Earth's surface. Due to the decrease in gas density, the temperature drops from 0 °C in the stratosphere to -110 °C in the mesosphere. However, the kinetic energy of individual particles at altitudes of 200–250 km corresponds to a temperature of ~1500°C. Above 200 km, significant fluctuations in temperature and gas density are observed in time and space.

At an altitude of about 2000-3000 km, the exosphere gradually passes into the so-called near space vacuum, which is filled with highly rarefied particles of interplanetary gas, mainly hydrogen atoms. But this gas is only part of the interplanetary matter. The other part is composed of dust-like particles of cometary and meteoric origin. In addition to extremely rarefied dust-like particles, electromagnetic and corpuscular radiation of solar and galactic origin penetrates into this space.

The troposphere accounts for about 80% of the mass of the atmosphere, the stratosphere accounts for about 20%; the mass of the mesosphere is no more than 0.3%, the thermosphere is less than 0.05% of the total mass of the atmosphere. Based on the electrical properties in the atmosphere, the neutrosphere and ionosphere are distinguished. It is currently believed that the atmosphere extends to an altitude of 2000-3000 km.

Depending on the composition of the gas in the atmosphere, they emit homosphere And heterosphere. heterosphere- this is an area where gravity affects the separation of gases, since their mixing at such a height is negligible. Hence follows the variable composition of the heterosphere. Below it lies a well-mixed, homogeneous part of the atmosphere, called the homosphere. The boundary between these layers is called turbopause, it lies at an altitude of about 120 km.

Physical properties

The thickness of the atmosphere is approximately 2000 - 3000 km from the Earth's surface. The total mass of air - (5.1-5.3)? 10 18 kg. The molar mass of clean dry air is 28.966. Pressure at 0 °C at sea level 101.325 kPa; critical temperature ?140.7 °C; critical pressure 3.7 MPa; C p 1.0048?10? J / (kg K) (at 0 °C), C v 0.7159 10? J/(kg K) (at 0 °C). Solubility of air in water at 0°С - 0.036%, at 25°С - 0.22%.

Physiological and other properties of the atmosphere

Already at an altitude of 5 km above sea level, an untrained person develops oxygen starvation and, without adaptation, a person's performance is significantly reduced. This is where the physiological zone of the atmosphere ends. Human breathing becomes impossible at an altitude of 15 km, although up to about 115 km the atmosphere contains oxygen.

The atmosphere provides us with the oxygen we need to breathe. However, due to the drop in the total pressure of the atmosphere as you rise to a height, the partial pressure of oxygen also decreases accordingly.

The human lungs constantly contain about 3 liters of alveolar air. The partial pressure of oxygen in the alveolar air at normal atmospheric pressure is 110 mm Hg. Art., pressure of carbon dioxide - 40 mm Hg. Art., and water vapor - 47 mm Hg. Art. With increasing altitude, the oxygen pressure drops, and the total pressure of water vapor and carbon dioxide in the lungs remains almost constant - about 87 mm Hg. Art. The flow of oxygen into the lungs will completely stop when the pressure of the surrounding air becomes equal to this value.

At an altitude of about 19-20 km, the atmospheric pressure drops to 47 mm Hg. Art. Therefore, at this height, water and interstitial fluid begin to boil in the human body. Outside the pressurized cabin at these altitudes, death occurs almost instantly. Thus, from the point of view of human physiology, "space" begins already at an altitude of 15-19 km.

Dense layers of air - the troposphere and stratosphere - protect us from the damaging effects of radiation. With sufficient rarefaction of air, at altitudes of more than 36 km, ionizing radiation, primary cosmic rays, has an intense effect on the body; at altitudes of more than 40 km, the ultraviolet part of the solar spectrum, which is dangerous for humans, operates.

As we rise to an ever greater height above the Earth's surface, gradually weaken, and then completely disappear, such phenomena that are familiar to us observed in the lower layers of the atmosphere, such as the propagation of sound, the occurrence of aerodynamic lift and resistance, heat transfer by convection, etc.

In rarefied layers of air, the propagation of sound is impossible. Up to altitudes of 60-90 km, it is still possible to use air resistance and lift for controlled aerodynamic flight. But starting from altitudes of 100-130 km, the concepts of the M number and the sound barrier familiar to every pilot lose their meaning, there passes the conditional Karman Line, beyond which the sphere of purely ballistic flight begins, which can only be controlled using reactive forces.

At altitudes above 100 km, the atmosphere is also deprived of another remarkable property - the ability to absorb, conduct and transfer thermal energy by convection (i.e., by means of air mixing). This means that various elements of equipment, equipment of the orbital space station will not be able to be cooled from the outside in the way it is usually done on an airplane - with the help of air jets and air radiators. At such a height, as in space in general, the only way to transfer heat is thermal radiation.

Composition of the atmosphere

The Earth's atmosphere consists mainly of gases and various impurities (dust, water drops, ice crystals, sea salts, combustion products).

The concentration of gases that make up the atmosphere is almost constant, with the exception of water (H 2 O) and carbon dioxide (CO 2).

| Gas | Content by volume, % |

Content by weight, % |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen | 78,084 | 75,50 |

| Oxygen | 20,946 | 23,10 |

| Argon | 0,932 | 1,286 |

| Water | 0,5-4 | - |

| Carbon dioxide | 0,032 | 0,046 |

| Neon | 1.818×10 −3 | 1.3×10 −3 |

| Helium | 4.6×10 −4 | 7.2×10 −5 |

| Methane | 1.7×10 −4 | - |

| Krypton | 1.14×10 −4 | 2.9×10 −4 |

| Hydrogen | 5×10 −5 | 7.6×10 −5 |

| Xenon | 8.7×10 −6 | - |

| Nitrous oxide | 5×10 −5 | 7.7×10 −5 |

In addition to the gases indicated in the table, the atmosphere contains SO 2, NH 3, CO, ozone, hydrocarbons, HCl, vapors, I 2, as well as many other gases in small quantities. In the troposphere there is constantly a large amount of suspended solid and liquid particles (aerosol).

History of the formation of the atmosphere

According to the most common theory, the Earth's atmosphere has been in four different compositions over time. Initially, it consisted of light gases (hydrogen and helium) captured from interplanetary space. This so-called primary atmosphere(about four billion years ago). At the next stage, active volcanic activity led to the saturation of the atmosphere with gases other than hydrogen (carbon dioxide, ammonia, water vapor). This is how secondary atmosphere(about three billion years before our days). This atmosphere was restorative. Further, the process of formation of the atmosphere was determined by the following factors:

- leakage of light gases (hydrogen and helium) into interplanetary space;