The book shows which of the mentioned mental operations can be found in animals and what degree of complexity of these operations is inherent in them.

In order to select criteria for the precise definition of those acts of animal behavior that can really be considered the rudiments of thinking, it seems to us that special attention should be paid to the formulation of the neuropsychologist A.

R. Luria (1966). His definition of the concept of "thinking" (in relation to man) allows us to more accurately distinguish this process from other types of mental activity and provides reliable criteria for identifying the rudiments of thinking in animals.

According to A. R. Luria, “the act of thinking occurs only when the subject has an appropriate motive that makes the task relevant, and its solution is necessary, and when the subject finds himself in a situation regarding the way out of which he does not have a ready solution - the usual (t .e. acquired in the process of learning) or congenital.

In other words, we are talking about acts of behavior, the execution program of which must be created urgently, in accordance with the conditions of the task, and by its nature does not require the selection of “correct” actions by the “trial and error” method.

The criteria for the presence of the rudiments of thinking in animals can be the following signs:

* "an emergency appearance of an answer in the absence of a ready-made solution" (Luria, 1966);

* "cognitive highlighting objective conditions essential for action” (Rubinshtein, 1958);

* “generalized, mediated nature of the reflection of reality; finding and discovery of something essentially new” (Brushlinsky, 1983);

* "presence and fulfillment of intermediate goals" (Leontiev, 1979).

Studies of the elements of thinking in animals are carried out in two main directions, making it possible to establish whether they have:

* the ability in new situations to solve unfamiliar problems for which there is no ready-made solution, i.e., to urgently capture the structure of the problem (“insight”) (see Chapter 4);

* the ability to generalize and abstract in the form of the formation of preverbal concepts and operating with symbols (see ch. 5, 6).

At the same time, in all periods of studying this problem, researchers tried to answer two equally important and closely related questions:

1. What are the highest forms of thinking available to animals, and what degree of similarity with human thinking can they achieve? The answer to this question is related to the study of the psyche of great apes and their ability to master intermediary languages (Chapter 6).

2. At what stages of phylogenesis did the first, most simple rudiments of thinking arise, and how widely are they represented in modern animals? To resolve this issue, extensive comparative studies of vertebrates at different levels of phylogenetic development are needed. In this book, they are considered on the example of the works of L. V. Krushinsky (see ch. 4, 8).

As we have already mentioned, until recently, the problems of thinking were practically not the subject of separate consideration in manuals on animal behavior, higher nervous activity, and zoopsychology.

If the authors touched on this problem, they tried to convince readers of the weak development of their rational activity and the presence of a sharp (impassable) line between the human and animal psyches. C. E. Fabry, in particular, wrote in 1976:

“The intellectual abilities of monkeys, including anthropoids, are limited by the fact that all their mental activity is biologically determined, therefore they are incapable of establishing a mental connection between representations alone and their combination into images” (highlighted by us. - Auth.).

Meanwhile, over the past 15-20 years, a huge amount of new and diverse data has been accumulated, which make it possible to more accurately assess the capabilities of animal thinking, the degree of development of elementary thinking in representatives of different species, and the degree of its closeness to human thinking.

To date, the following ideas about the thinking of animals have been formulated.

* The rudiments of thinking are found in a fairly wide range of vertebrate species - reptiles, birds, mammals of various orders. In the most highly developed mammals - great apes - the ability to generalize makes it possible to assimilate and use intermediary languages at the level of 2-year-old children (see Chapters 6, 7).

* Elements of thinking are manifested in animals in different forms. They can be expressed in the performance of many operations, such as generalization, abstraction, comparison, logical conclusion, emergency decision-making by operating with empirical laws, etc. (see Chapters 4, 5).

* Reasonable acts in animals are associated with the processing of multiple sensory information (sound, olfactory, different types of visual - spatial, quantitative, geo-

metric) in various functional areas - food-producing, defensive, social, parental, etc. Animal thinking is not just the ability to solve a particular problem. This is a systemic property of the brain, and the higher the phylogenetic level of an animal and the corresponding structural and functional organization of its brain, the greater the range of intellectual capabilities it possesses.

To designate higher forms cognitive (cognitive) activity of a person, there are terms - "mind", "thinking", "reason", "reasonable behavior". When using the same terms when describing the thinking of animals, it must be remembered that no matter how complex the manifestations of higher forms of behavior and the psyche of animals in the material discussed below, we can only talk about the elements and rudiments of the corresponding mental functions of a person. L. V. Krushinsky’s term “rational activity” makes it possible to avoid complete identification of the mental processes in animals and humans, which differ significantly in degree of complexity.

1. What areas of biology study animal behavior?

2. On what principles are the classifications of animal behavior based?

3. What are the questions facing scientists who study the thinking of animals?

4. What are the main directions in the study of animal thinking?

More on the topic of human thinking and the rational activity of animals:

- 4 ELEMENTARY THINKING, OR RUDENTAL ACTIVITY, OF ANIMALS:

- 4.4. Classification of tests used to study the rational activity (thinking) of animals

- 8.2. Comparative characteristics of the level of elementary rational activity (elementary thinking) in animals of different taxonomic groups

- 2.11.3. Significance of the works of ETOAOGOV for assessing the rational activity of animals

- 2.7. The doctrine of higher nervous activity and the problem of animal thinking

- 9 GENETIC STUDIES OF ELEMENTARY CONSCIOUS ACTIVITY AND OTHER COGNITIVE ABILITIES OF ANIMALS

Is there an insurmountable boundary between human thinking and elements of the rational activity of animals? Is our species truly unique in this respect? And to what extent are these differences qualitative, or maybe they are only quantitative? And can we say that all our abilities, such as reason, consciousness, memory, speech, the ability to generalize, to abstract, are so unique? Or, perhaps, all this is a direct continuation of those tendencies in the evolution of higher nervous activity that are observed in the animal world?

These questions are answered by the head of the laboratory of physiology and genetics of behavior of the Faculty of Biology, Moscow State University, Dr. biological sciences Zoya Alexandrovna Zorina: “The unique abilities of a person, his thinking really have biological prerequisites. And between the human psyche and the psyche of animals there is no that impassable abyss, which for a long time was somehow attributed and implied by default. And even in mid-nineteenth For centuries, Darwin said about this that the difference between the psyche of man and animals, no matter how great it may be, is a difference in degree, not in quality.

Consequently, at some point they stopped believing in Darwin.

Maybe they did not believe or left aside. Then this thought was too prescient. And this is not a question of faith, but of facts and evidence. Experimental study of the psyche of animals began in the 20th century, at the very beginning of the 20th century. And the entire 20th century is a history of discoveries, a history of approaching the recognition of the position that human thinking clearly has biological prerequisites, including its most complex forms, such as human speech. And the proof of the latter position was achieved only at the end of the 20th century, the last third. And now these studies continue to develop rapidly and brilliantly. The fact that primates are approaching humans, especially anthropoids, is somehow imaginable. But a more unexpected and not so conspicuous fact is that the rudiments of thinking, in general, appeared at earlier stages of phylogenetic development in more primitive animals. Human thinking has distant and deep roots.

Is there even a definition of thinking? How to formally draw the line between instinctive, meaningless behavior and thinking?

Let's start from the definition of thinking given by psychologists, that thinking is primarily a generalized mediated reflection of reality. Do animals have it? There is. To varying degrees, it is studied and shown to what extent it is generalized and in whom and to what extent it is mediated. Further: thinking is based on the arbitrary operation of images. And this side of the animal psyche has also been studied and shown to exist. A good key is the definition of Alexander Luria, who said that the act of thinking occurs only when the subject has a motive that makes the task urgent, and its solution is necessary, and when the subject does not have a ready solution. What does ready mean? When there is no instinctive, soldered program, algorithm, instinct.

The algorithm can be written down, but the solution to the problem is much more difficult to obtain.

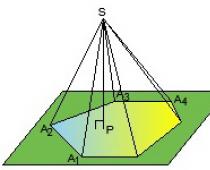

When an animal does not have this hereditary algorithm, when there is no opportunity to learn it, there is no time and conditions to make trial and error that underlie the acquired behavior, and when a solution needs to be created in an emergency way, right now, based on some express information. Thinking is problem solving, on the one hand, on the other hand, a parallel process is a constant processing of information, its generalization, abstraction. In humans, this is the formation of verbal concepts, but in animals, since there are no words, it means that there should not be generalizations. Modern research is one of the aspects of the development of the science of animal thinking, the study of their ability to generalize, that is, to mentally combine objects, phenomena, events according to their common essential properties. It turns out that animals are not only capable of such a primitive empirical generalization in terms of color and shape, but they are also capable of isolating rather abstract features, when information, as a result of generalization, acquires a highly abstract form, although it is not connected with the word. I will give an example from our research - this is a generalization of the sign of similarity. Here are the crows we work on, able to learn to sort the stimuli presented to them for the choice of a pair, to choose from them the stimulus that is similar to the sample offered to them. First, a black card is shown to the bird, in front of it are two feeders covered with a black lid and a white lid. She learns long and hard to choose black if the sample is black, to choose white if the sample is white. This requires a lot of time and work from both us and the bird. And then we show her the numbers. And now she sees the number two, chooses two, not three and not five. The number three - chooses three, not four or five. Chooses the same. When we ask her to choose, say, cards with different types hatching, she learns already faster. Then we offer her a lot: choose three points on the sample, then choose any stimulus, where there are three elements, let them be crosses, zeros, anything, but three, and on other cards four, two, one. And with successive steps each time she needs to learn less and less time, although decently. But there comes a moment, we call it a transfer test, when we offer completely new stimuli, for example, instead of numbers from 1 to 4 - numbers from 5 to 8. For the correct choice, each time she receives her reinforcement. We present a well-trained crow with stimuli of another category, new, unfamiliar to it. A new set of squiggles, from the very first time they clearly choose completely according to the principle - the same, similar. And then we offered them figures of different shapes and offered them to choose: on the sample there is a small figure, and two other geometric figures are offered for choice - one small, the other large, there is no more similarity, only size. And the crow, seeing a small square, chooses a small square if there is a small pyramid on the sample. And this is a sign of another category - this is a similarity in size, nothing similar, in common with the initial moment, choose black, if black, there is no more. It's high abstract feature: choose any stimulus that matches the pattern. In this case, similar in size, regardless of shape. Thus, our classicist Leonid Alexandrovich Firsov, a Leningrad primatologist, formulated ideas about preverbal concepts, when animals reach such a level of abstraction that they form concepts, preverbal concepts about similarity in general. And Firsov even had such a work "The pre-verbal language of monkeys." Because a lot of information, apparently, is stored in such an abstract form, but not verbalized. But the work of the late 20th century, mainly by our American colleagues, work on great apes, shows that under certain conditions, monkeys can associate preverbal representations, preverbal concepts with certain signs, not with spoken words, they just can't say anything, but they associate it with signs of the deaf and dumb language or with the icons of a certain artificial language.

Zoya Alexandrovna, say a few words about the evolutionary development of thinking. We can say whether there is any relationship between the complexity of the structure nervous system and complexity of behavior? How did it develop in evolution?

Speaking from the most general positions, the key here, probably, can be the long-standing work of Alexei Nikolaevich Severtsev, who said that the evolution of the psyche went not only in the direction of developing specific programs, such as instincts, but in the direction of increasing the potential ability to solve different problems. kind of tasks, increasing some general plasticity. He said that in animals, highly organized animals, due to this, a certain potential psyche or spare mind is created. The higher the animal is organized, we see, in fact, this is also in the experiment, it is precisely these potential abilities that manifest themselves, are revealed by the experiment and sometimes manifest themselves in real life. When they began to observe the behavior of gorillas in nature, then, reading Shaler's diaries, one could think that he was watching a herd of cows, because: they fed there, slept, ate, crossed, such trees, other trees. But at the same time, the same gorillas, the same chimpanzees and all anthropoids are capable of solving a bunch of problems, up to mastering the human language, which are completely absent, not to mention cows, I'm sorry, but simply not in demand in their real behavior. And the reserve of cognitive abilities in highly organized animals is huge. But the lower we go down, we move on to not so highly organized animals, this reserve, this potential psyche, becomes less and less. And one of the tasks of the biological prerequisites of human thinking is not only to understand where the upper bar is and how they approach a person, but also to find the simplest things, some universals, from where, from which everything originates.

| Comments: 0 |

Alexander Markov

A hypothesis is proposed, according to which the qualitative difference between the intellect of humans and monkeys is the lack of the latter's ability to think recursively, that is, to apply logical operations to the results of previous similar logical operations. The inability to recurse is due to the low capacity of " working memory”, which in monkeys cannot simultaneously accommodate more than two or three concepts (in humans - up to seven).

Anna Smirnova

Anna Smirnova's report was held on January 24, 2018 at the Moscow Ethological Seminar at the Institute of Ecology and Evolution Problems. A.N. Severtsov with the technical support of the Cultural and Educational Center "Arkhe".

Konstantin Anokhin

What are the principles of modern fundamental scientific theory consciousness? When was the first experimental evidence for the existence of episodic memory in animals? Neuroscientist Konstantin Anokhin on the scientific principles of the theory of consciousness, the phenomenon of "time travel" and episodic memory in animals.

Zoya Zorina, Inga Poletaeva

The textbook is devoted to elementary thinking, or rational activity - the most complex form of animal behavior. For the first time, the reader is offered a synthesis of classical works and the latest data in this area obtained by zoopsychologists, physiologists of higher nervous activity and ethologists. The manual reflects the content of the lecture courses that the authors have been giving for many years at the Moscow State University them. M. V. Lomonosov and other universities. An extensive list of references is intended for those wishing to continue their acquaintance with the problem on their own. The manual is intended for students and teachers of biological and psychological faculties of universities and pedagogical universities

The textbook is devoted to elementary thinking, or rational activity - the most complex form of animal behavior. For the first time, the reader is offered a synthesis of classical works and the latest data in this area obtained by zoopsychologists, physiologists of higher nervous activity and ethologists. The manual reflects the content of the lecture courses that the authors have been giving for many years at the Moscow State University them. M. V. Lomonosov and other universities. An extensive list of references is intended for those wishing to continue their acquaintance with the problem on their own. The manual is intended for students and teachers of biological and psychological faculties of universities and pedagogical universities

The presence of elements of the mind in higher animals is currently beyond doubt by any of the scientists. Intellectual behavior represents the pinnacle of the mental development of animals. At the same time, as L.V. Krushinsky, it is not something out of the ordinary, but only one of the manifestations of complex forms of behavior with their innate and acquired aspects. Intellectual behavior is not only closely related to various forms of instinctive behavior and learning, but is itself made up of individually variable components of behavior. It gives the greatest adaptive effect and contributes to the survival of individuals and the continuation of the genus during abrupt, rapidly occurring changes in the environment. At the same time, the intellect of even the highest animals is undoubtedly at a lower stage of development than the human intellect, so it would be more correct to call it elementary thinking, or the rudiments of thinking. The biological study of this problem has come a long way, and all the leading scientists have invariably returned to it. The history of the study of elementary thinking in animals has already been discussed in the first sections of this manual, so in this chapter we will only try to systematize the results of its experimental study.

Definition of human thinking and intelligence

Before talking about the elementary thinking of animals, it is necessary to clarify how psychologists define human thinking and intelligence. At present, in psychology, there are several definitions of these most complex phenomena, however, since this problem is beyond the scope of our training course, we will limit ourselves to the most general information.

According to A.R. Luria, "the act of thinking arises only when the subject has an appropriate motive that makes the task relevant, and its solution is necessary, and when the subject finds himself in a situation regarding the way out of which he does not have a ready-made solution - familiar (i.e., acquired in learning process) or innate".

Thinking is the most complex form of human mental activity, the top of its evolutionary development. A very important apparatus of human thinking, which significantly complicates its structure, is speech, which allows you to encode information using abstract symbols.

The term "intelligence" is used both broadly and in narrow sense. In a broad sense, intelligence is the totality of all cognitive functions of an individual, from sensation and perception to thinking and imagination, in a narrower sense, intelligence is thinking itself.

In the process of human cognition of reality, psychologists note three main functions of the intellect:

● ability to learn;

● operating with symbols;

● ability to actively master patterns environment.

Psychologists distinguish the following forms of human thinking:

● visual-effective, based on the direct perception of objects in the process of actions with them;

● figurative, based on ideas and images;

● inductive, based on the logical conclusion "from the particular to the general" (construction of analogies);

● deductive, based on a logical conclusion "from the general to the particular" or "from the particular to the particular", made in accordance with the rules of logic;

● abstract-logical, or verbal, thinking, which is the most complex form.

Verbal thinking of a person is inextricably linked with speech. It is thanks to speech, i.e. the second signal system, human thinking becomes generalized and mediated.

It is generally accepted that the process of thinking is carried out with the help of the following mental operations - analysis, synthesis, comparison, generalization and abstraction. The result of the process of thinking in humans are concepts, judgments and conclusions.

The problem of animal intelligence

Intellectual behavior is the pinnacle of the mental development of animals. However, speaking about the intellect, the "mind" of animals, they must first be noted that it is extremely difficult to specify exactly which animals can be talked about intellectual behavior, and which ones can not. Obviously, we can only talk about higher vertebrates, but obviously not only about primates, as was accepted until recently. At the same time, the intellectual behavior of animals is not something isolated, out of the ordinary, but only one of the manifestations of a single mental activity with its innate and acquired aspects. Intellectual behavior is not only closely connected with various forms of instinctive behavior and learning, but is itself composed (on an innate basis) of individually variable components of behavior. It is the highest result and manifestation of individual accumulation of experience, a special category of learning with its inherent qualitative features. Therefore, intellectual behavior gives the greatest adaptive effect, to which A.N. Severtsov paid special attention, showing the decisive importance of higher mental abilities for the survival of individuals and procreation in the face of abrupt, rapidly occurring changes in the environment.

The prerequisite and basis for the development of animal intelligence is manipulation, primarily with biologically "neutral" objects. This is especially true for monkeys, for whom manipulation serves as a source of the most complete information about the properties and structure of the objective components of the environment, because in the course of manipulation, the deepest and most comprehensive acquaintance with new objects or new properties of objects already familiar to the animal occurs. In the course of manipulation, especially when performing complex manipulations, the experience of the animal's activity is generalized, generalized knowledge about the subject components of the environment is formed, and it is this generalized motor-sensory experience that forms the main basis of the monkeys' intelligence.

Destructive actions are of particular cognitive value, as they allow one to obtain information about internal structure items. During manipulation, the animal receives information simultaneously through a number of sensory channels, but the combination of skin-muscular sensitivity of the hands with visual sensations is of predominant importance. As a result, animals receive complex information about the object as a whole and having properties of different qualities. This is precisely the meaning of manipulation as the basis of intellectual behavior.

An extremely important prerequisite for intellectual behavior is the ability to broadly transfer skills to new situations. This ability is fully developed in higher vertebrates, although it manifests itself in different animals to different degrees. The abilities of higher vertebrates for various manipulations, for broad sensory generalization, for solving complex problems and transferring complex skills to new situations, for full orientation and adequate response in a new environment based on previous experience, are the most important elements of animal intelligence. And yet, in themselves, these qualities are still insufficient to serve as criteria for the intellect, the thinking of animals.

A distinctive feature of the intelligence of animals is that in addition to the reflection of individual things, there is a reflection of their relationships and connections. This reflection occurs in the process of activity, which, according to Leontiev, is two-phase in its structure.

With the development of intellectual forms of behavior, the phases of solving the problem acquire a clear heterogeneity: previously merged into single process activity is differentiated into a preparation phase and an implementation phase. It is the preparation phase that feature intellectual behaviour. The second phase includes, in itself, a certain operation, fixed in the form of a skill.

Of great importance as one of the criteria of intellectual behavior is the fact that when solving a problem, the animal uses not one stereotypically performed method, but tries different methods that are the result of previously accumulated experience. Consequently, instead of trials of different movements, as is the case with non-intellectual actions, with intellectual behavior there are trials of various operations, which makes it possible to solve the same problem in different ways. The transference and trials of various operations in solving a complex problem find their expression among monkeys, in particular, in the fact that they practically never use tools in exactly the same way.

Along with all this, one must clearly understand the biological limitations of the intelligence of animals. Like all other forms of behavior, it is entirely determined by the way of life and purely biological laws, the limits of which even the most intelligent monkey cannot step over.

In conclusion, we have to admit that the problem of animal intelligence is still completely insufficiently studied. In essence, detailed experimental studies have so far been carried out only on monkeys, mainly higher ones, while there is still almost no evidence-based experimental data on the possibility of intellectual actions in other vertebrates. However, it is doubtful that intelligence is unique to primates.

Human thinking and the rational activity of animals

According to leading Russian psychologists, the criteria for the presence of the rudiments of thinking in animals can be the following signs:

● "an emergency appearance of an answer in the absence of a ready-made solution" (Luria);

● "cognitive selection of objective conditions essential for action" (Rubinshtein);

● "generalized, mediated nature of the reflection of reality; the search for and discovery of an essentially new" (Brushlinsky);

● "presence and fulfillment of intermediate goals" (Leontiev).

Human thinking has a number of synonyms, such as: "reason", "intellect", "reason", etc. However, when using these terms to describe the thinking of animals, it must be borne in mind that, no matter how complex their behavior may be, we can only talk about the elements and rudiments of the corresponding mental functions of a person.

The most correct is the one proposed by L.V. Krushinsky termed rational activity. It avoids the identification of thought processes in animals and humans. The most characteristic property of the rational activity of animals is their ability to capture the simplest empirical laws that connect objects and phenomena of the environment, and the ability to operate with these laws when building programs of behavior in new situations.

Reasoning activity different from any form of education. This form of adaptive behavior can be carried out at the first meeting of the organism with unusual situation created in its habitat. The fact that an animal can immediately, without special training, decide to adequately perform a behavioral act, is the unique feature of rational activity as an adaptive mechanism in diverse, constantly changing environmental conditions. Reasoning activity allows us to consider the adaptive functions of the body not only as self-regulating, but also self-selecting systems. This implies the ability of an organism to make an adequate choice of the most biologically appropriate forms of behavior in new situations. By definition L.V. Krushinsky, rational activity is the performance by an animal of an adaptive behavioral act in an emergency situation. This unique way of adapting the organism in the environment is possible in animals with a well-developed nervous system.

Zorina Zoya Aleksandrovna, Poletaeva Inga Igorevna

The main experimental data on the thinking of animals, on the ability to urgently solve new problems for which they do not have a "ready" solution. Analysis of the main views on the nature of animal thinking. Determining the requirements that must be observed when planning, conducting and processing the results of experiments. Description of the methods of studying the rational activity of animals. Comparison of experiments on tool activity and characteristics of its manifestations during the life of animals in natural conditions. Brief comparative characteristics solving elementary logical problems by animals of different taxonomic groups. Substantiation of the need for complex versatile testing to obtain a full-fledged characteristic of the level of rational activity of the species.

The following sections are devoted to the experimental study of this form of cognitive activity, which differs in its adaptive functions and mechanisms from instincts and the ability to learn.

1. Definitions of the concept of "thinking animals".

Previously given short description structures of human thinking and the criteria that an act of behavior of an animal must meet in order to see the participation of the thinking process in it are named. Recall that A. R. Luria’s definition was chosen as the key one, according to which “the act of thinking occurs only when the subject has an appropriate motive that makes the task relevant, and its solution is necessary, and when the subject finds himself in a situation regarding the exit from which he does not have a ready-made solution (italics ours. - Auth.) - habitual (i.e. acquired in the learning process) or innate.

In other words, we are talking about acts of behavior, the program of which must be created urgently, in accordance with the conditions of the task, and by its nature does not require actions that are trial and error.

Human thinking is a multifaceted process, including the ability to generalize and abstract, developed to the level of symbolization, and anticipation of the new, and solving problems through an urgent analysis of their conditions and identifying underlying patterns. The definitions given to the thinking of animals by different authors reflect in a similar way all sorts of aspects of this process, depending on what forms of thinking are revealed by certain experiments.

Modern ideas about the thinking of animals have evolved throughout the 20th century and largely reflect the methodological approaches used by the authors of the research. The time interval between some works in this direction was more than half a century, so their comparison allows us to trace how views on this extremely complex form of higher nervous activity have changed.

In highly organized animals (primates, dolphins, corvids), thinking is not limited to the ability to solve individual problems, but is a systemic function of the brain, which manifests itself when solving various tests in the experiment and in the most different situations in natural environment habitat.

V. Koehler (1925), who first studied the problem of animal thinking in an experiment (see 2.6), came to the conclusion that great apes have an intellect that allows them to solve some problem situations not by trial and error, but due to a special mechanism - “ insight” (“penetration” or “insight”), i.e. by understanding the relationships between stimuli and events.

According to W. Koehler, insight is based on the tendency to perceive the whole situation as a whole and, thanks to this, make an adequate decision, and not just automatically respond with individual reactions to individual stimuli.

The term "insight" proposed by V. Koehler entered the literature to refer to cases of reasonable comprehension inner nature tasks. This term is also actively used at the present time in the study of animal behavior to designate their sudden solutions to new problems, for example, in describing the behavior of monkeys mastering Amslen (Chapter 6).

A contemporary and like-minded person of V. Koehler, the American researcher R. Yerkes, based on various experiments with great apes, came to the conclusion that their cognitive activity is based on “processes other than reinforcement and inhibition. It can be assumed that in the near future these processes will be considered as the forerunners of human symbolic thinking ... ”(our italics. - Auth.).

The presence of thinking in animals was admitted by IP Pavlov (see 2.7). He assessed this process as "the beginnings of concrete thinking, which we also use" and emphasized that it cannot be identified with conditioned reflexes. According to I.P. Pavlov, one can speak about thinking when two phenomena are connected, which in reality are constantly connected: “This will already be a different kind of the same association, which has a value, perhaps not less, but rather more, than conditioned reflexes - a signal connection.

The American psychologist N. Mayer (Maier, 1929) showed that one of the varieties of animal thinking is the ability to respond adequately in a new situation due to an emergency reorganization of previously acquired skills, i.e. due to the ability to "spontaneously integrate isolated elements of past experience, creating a new behavioral response adequate to the situation" (see also 2.8). L. G. Voronin (1984) came to a similar idea in a completely independent way, although in his early works he was skeptical about the hypothesis that animals have rational activity. According to L. G. Voronin, the most complex level of analytical and synthetic activity of the brain of animals is the ability to combine and recombine conditional connections stored in memory and systems of them. He called this ability combinational SD and considered it as the basis for the formation of figurative, concrete thinking (below, modern methods for studying this form of thinking are considered - 8).

N. N. Ladygina-Kots (1963) wrote that “monkeys have an elementary concrete creative thinking(intelligence), capable of elementary abstraction (in concrete) and generalization. And these features bring their psyche closer to the human. At the same time, she emphasized that “... their intellect is qualitatively, fundamentally different from the conceptual thinking of a person who has a language, operating words as signals of signals, a system of codes, while the sounds of monkeys, although extremely diverse, express only their emotional state and have no directional character. Monkeys, like all other animals, have only the first signal system of reality.

Ability to urgently solve new problems. The ability to establish "new connections in new situations" is an important property of animal thinking (Dembovsky, 1963; 1997; Ladygina-Kots, 1963; 1997; Roginsky, 1948).

L. V. Krushinsky (1986) investigated this ability as the basis of the elementary thinking of animals.

Thinking, or rational activity (according to Krushinsky), is “the ability of an animal to capture empirical laws that connect objects and phenomena outside world, and operate with these laws in a new situation for him to build a program of an adaptive behavioral act.

At the same time, L. V. Krushinsky had in mind situations where the animal does not have a ready-made solution program, formed as a result of training or due to instinct.

Recall that these are precisely the features that are noted in the definition of human thinking given by A. R. Luria (1966). At the same time, as L. V. Krushinsky emphasizes, these are situations, the way out of which can be found not by trial and error, but by a logical way, based on a mental analysis of the conditions of the problem. According to his terminology, the solution is carried out on the basis of "capturing the empirical laws that connect objects and phenomena of the external world" (see 6).

The American researcher D. Rambo, who analyzes the process of symbolization in anthropoids, emphasizes the cognitive nature of this phenomenon and considers the thinking of animals as "adequate behavior based on the perception of connections between objects, on the idea of missing objects, on the hidden operation of symbols" (Rumbaugh, Pate, 1984 ) (our italics. - Auth.).

Another American researcher, D. Primek (Premack, 1986) also comes to the conclusion that the "linguistic" abilities of chimpanzees (a complex form of communicative behavior) are associated with "mental processes of a higher order."

Among such processes, Primek refers to the ability to preserve "a network of perceptual image-representations, to use symbols, as well as to mentally reorganize the idea of a sequence of events."

Not limited to teaching chimpanzees the intermediary language he created (see 2.9.2), Primek has developed and largely implemented a comprehensive program of studying the mind of animals. He singled out the following situations that need to be investigated in order to prove the existence of thinking in animals:

solving problems simulating natural situations for an animal (“natural reasoning”);

construction of analogies (“analogical reasoning”, see Chapter 5);

implementation of logical inference operations (“inferential reasoning”);

ability for self-awareness.

An American researcher Richard Byrne (Byrne, 1998) gave a comprehensive description of the intelligence of animals in his book "Thinking Anthropoids". In his opinion, the concept of "intelligence" includes the ability of an individual:

extract knowledge from interactions with the environment and relatives;

use this knowledge to organize effective behavior in both familiar and new circumstances;

resort to thinking (“thinking”), reasoning (“reasoning”) or planning (“planning”) when a task arises;

According to leading Russian psychologists, The criteria for the presence in animals of the rudiments of thinking can be the following signs:

"emergency appearance of the answer in the absence of a ready-made solution"(Luria) the act of thinking arises only when the subject has an appropriate motive that makes the task relevant, and its solution necessary, and when the subject finds himself in a situation regarding the way out of which he does not have a ready-made solution - familiar (i.e., acquired in learning process) or innate”;

"cognitive identification of objective conditions essential for action"(Rubinstein);

"generalized, mediated nature of the reflection of reality; the search and discovery of an essentially new"(Brushlinsky);

"presence and fulfillment of intermediate goals"(Leontiev).

Human thinking has a number of synonyms, such as: "reason", "intellect", "reason", etc. However, when using these terms to describe the thinking of animals, it must be borne in mind that, no matter how complex their behavior may be, we can only talk about the elements and rudiments of the corresponding mental functions of a person.

The most correct one is the one proposed. L.V. Krushinsky term rationalactivities b. It avoids the identification of thought processes in animals and humans. Reasoning activity is different from any form of learning. This form of adaptive behavior can be when an organism first encounters an unusual situation created in its habitat. The fact that the animal immediately, without special training, can decide to adequate performance of a behavioral act, and this is the unique feature of rational activity as an adaptive mechanism in diverse, constantly changing environmental conditions. Reasoning activity allows us to consider the adaptive functions of the body not only as self-regulating, but also self-selecting systems. This implies the ability of an organism to make an adequate choice of the most biologically appropriate forms of behavior in new situations. By definition L.V. Krushinsky, rational activity is the performance by an animal of an adaptive behavioral act in an emergency situation.. This unique way of adapting the organism in the environment is possible in animals with a well-developed nervous system.

To date, the following ideas about the thinking of animals have been formulated.

The rudiments of thinking are present in a fairly wide range of vertebrate species - reptiles, birds, mammals of various orders. In the most highly developed mammals - great apes - the ability to generalize makes it possible to assimilate and use intermediary languages at the level of 2-year-old children.

The elements of thought appear in animals in various forms. They can be expressed in the performance of many operations, such as generalization, abstraction, comparison, inference.

Reasonable acts in animals are associated with the processing of multiple sensory information (sound, olfactory, various types of visual-spatial, quantitative, geometric) in various functional areas - food-procuring, defensive, social, parental, etc.

Animal thinking is not just the ability to solve a particular problem. This is a systemic property of the brain, and the higher the phylogenetic level of an animal and the corresponding structural and functional organization of its brain, the greater the range of intellectual capabilities it possesses.

In highly organized animals (primates, dolphins, corvids), thinking is not limited to the ability to solve individual problems, but is a systemic brain function that manifests itself when solving various tests in the experiment and in a variety of situations in the natural habitat.

W. Koehler(1925), who first studied the problem of animal thinking in an experiment, came to the conclusion that great apes have an intellect that allows them to solve some problem situations not by trial and error, but due to a special mechanism - “insight” (“penetration” or “ insights”), i.e. by understanding the relationships between stimuli and events.

According to W. Koehler, insight is based on the tendency to perceive the whole situation as a whole and, thanks to this, make an adequate decision, and not just automatically respond with individual reactions to individual stimuli. ( insight"- conscious "planned" use of tools in accordance with their mental plan)

- In contact with 0

- Google Plus 0

- OK 0

- Facebook 0