They (blind. - L.V.) such features develop that we cannot notice in the sighted, and it must be assumed that in the case of exclusive communication between the blind and the blind, without any intercourse with the sighted, a special breed of people could arise.

K. Bürklen*

Leaving particulars aside and neglecting the details, one can imagine the development of scientific views on the psychology of the blind in the form of one line that goes from ancient times to the present day, now lost in the darkness of false ideas, then reappearing with each new conquest of science. As a magnetic needle points to the north, so this line points to the truth and allows us to evaluate any historical error by the degree of its deviation from this path by the angle of curvature of the main line.

______________________

* K. Burklen, 1924. S. 3.

In essence, the science of the blind man, in so far as it has been moving towards the truth, is all reduced to the unfolding of one central idea, which humanity has been trying to master for thousands of years, because it is not only an idea about the blind man, but also about the psychological nature of man in general. In the psychology of the blind, as in all knowledge, one can err in different ways, but there is only one way to go to the truth. This idea boils down to the fact that blindness is not only the absence of vision (a defect in a separate organ); it causes a profound restructuring of all the forces of the body and personality,

Blindness, creating a new, special personality, brings new forces to life, changes normal directions functions, creatively and organically recreates and shapes the human psyche. Consequently, blindness is not only a defect, a minus, a weakness, but also, in a sense, a source of the manifestation of abilities, a plus, a strength (however strange and similar to a paradox!).

This idea has gone through three main stages, from comparisons of which it becomes clear the direction, the trend of its development. The first era can be designated as mystical, the second - naive-biological and the third, modern - scientific or socio-psychological.

The first era covers antiquity, the Middle Ages and a significant part new history. Until now, the remnants of this era are visible in popular views on the blind, in legends, fairy tales, proverbs. Blindness was primarily seen as a great misfortune, which was treated with superstitious fear and respect. Along with the attitude towards the blind as a helpless, defenseless and abandoned being, there is a general belief that the blind develop the highest mystical powers of the soul, that spiritual knowledge and vision are available to them instead of the lost physical sight. Until now, many still talk about the striving of the blind for spiritual light: apparently, there is some truth in this, although it is distorted by the fear and misunderstanding of the religiously thinking mind. The keepers of folk wisdom, singers, soothsayers of the future, according to legend, were often blind. Homer was blind. It is said of Democritus that he himself blinded himself in order to devote himself fully to philosophy. If this is not true, then at least it is indicative: the very possibility of such a tradition, which no one seemed absurd, testifies to such a view of blindness, according to which the philosophical gift can be strengthened with loss of sight. Curiously, the Talmud, which equates the blind, the lepers, and the childless with the dead, when speaking of the blind, uses the euphemistic expression "a man with an abundance of light." German folk sayings and sayings of traditional wisdom bear traces of this same view: "The blind man wants to see everything" or "Solomon found wisdom in the blind, because they do not take a step without examining the ground on which they walk." O. Vanechek (O. Wanecek, 1919) in a study of a blind man in a saga, fairy tale and legend showed that folk art inherent in the view of the blind as a person with an awakened inner vision gifted with spiritual knowledge, alien to other people.

Christianity, which brought with it a reassessment of values, essentially changed only the moral content of this idea, but left the very essence unchanged. "The last ones here," which, of course, included the blind, were promised to be "the first ones there." In the Middle Ages, this was the most important dogma of the philosophy of blindness, in which, as in any deprivation, suffering, they saw a spiritual value; the church porch was given to the undivided possession of the blind. This signified both begging in earthly life and closeness to God. In a weak body, they said then, a lofty spirit lives. Again, in blindness, some mystical second side was revealed, some kind of spiritual value, some kind of positive meaning. This stage in the development of the psychology of the blind should be called mystical, not only because it was colored by religious ideas and beliefs, not only because the blind were brought closer to God in every possible way: visible, but not seeing - to the seer, but invisible, as they said Jewish sages.

In fact, the abilities that were attributed to the blind were considered supersensible powers of the soul, their connection with blindness seemed mysterious, wonderful, incomprehensible. These views arose not from experience, not from the testimony of the blind themselves about themselves, not from scientific research blind man and his social role, but from the doctrine of the spirit and body and faith in a disembodied spirit. And yet, although history has completely destroyed, and science has completely exposed the failure of this philosophy, a particle of truth was hidden in its deepest foundations.

Only the Age of Enlightenment (XVIII century) opened a new era in the understanding of blindness. In place of mysticism science was put, in place of prejudice - experience and study. The greatest historical significance of this era for the problem we are considering lies in the fact that a new understanding of psychology created (as its direct consequence) the upbringing and education of the blind, introducing them to social life and opening up access to culture.

In theoretical terms, a new understanding was expressed in the doctrine of the vicariate of the senses. According to this view, the loss of one of the functions of perception, the lack of one organ is compensated by the increased functioning and development of other organs. As in the case of the absence or illness of one of the paired organs - for example, the kidney or lung, another, healthy organ develops compensatory, increases and takes the place of the patient, taking on part of its functions, so the visual defect causes an increased development of hearing, touch and other remaining senses. . Entire legends were created about the supernormal acuity of touch in the blind; they spoke of the wisdom of good nature, which with one hand takes away, and with the other gives back what is taken away and cares for its creatures; believed that every blind man, thanks to this fact alone, is a blind musician, i.e. a person gifted with heightened and exceptional hearing; discovered a new, special, inaccessible sixth sense for the sighted in the blind. All these legends were based on true observations and facts from the life of the blind, but falsely interpreted and therefore distorted beyond recognition. K. Burklen collected the opinions of various authors (X.A. Fritsche, L. Bachko, Stuke, X.V. Rotermund, I.V. Klein, etc.), who developed this idea in various forms (K. Burklen, 1924) . However, research very soon revealed the inconsistency of such a theory. They pointed out, as an irrevocably established fact, that there is no supernormal development of the functions of touch and hearing in the blind; that, on the contrary, very often these functions are less developed in the blind than in the sighted; finally, where we meet with an increased function of touch in comparison with the normal one, this phenomenon turns out to be secondary, dependent, derivative, rather a consequence of development than its cause. This phenomenon arises not from direct physiological compensation for a visual defect (like an enlarged kidney), but by a very complex and indirect way of general socio-psychological compensation, without replacing the missing function and without taking the place of the missing organ.

Therefore, there can be no question of any vicariate of the sense organs. Luzardi rightly pointed out that the finger will never really teach the blind to see. E. Binder, following Appiah, showed that the functions of the sense organs are not transferred from one organ to another and that the expression "vicariate of the senses", i.e. substitution of sense organs is misused in physiology. Of decisive importance for the refutation of this dogma were the studies of Fisbach, published in the physiological archive of E. Pfluger and showing its inconsistency. The dispute was resolved by experimental psychology. She showed the way for a correct understanding of the facts that underlay this theory.

E. Meiman disputed Fisbach's position that with a defect in one sense, all senses suffer. He argued that in fact there is a kind of substitution of the functions of perception (E. Meumann, 1911). W. Wundt came to the conclusion that there is a replacement in the field of physiological functions special case exercises and equipment. Consequently, substitution should be understood not in the sense of direct acceptance by other organs of the physiological functions of the eye, but a complex restructuring of all mental activity caused by a violation of the most important function and directed through association, memory, attention to the creation and development of a new type of balance of the body to replace the disturbed one.

But if such a naive biological concept turned out to be wrong and was forced to give way to another theory, nevertheless it made a huge step forward towards the conquest of scientific truth about blindness. For the first time, with the yardstick of scientific observation and with the criterion of experience, she approached the fact that blindness is not only a defect, only insufficiency, but also calls into life and activity new forces, new functions and performs some kind of creative and creative organic work, although this theory could not specify what exactly such work consisted of. How big and big practical value such a step towards the truth, can be judged by the fact that this era created the education and education of the blind. One Braille dot has done more for the blind than thousands of benefactors; the ability to read and write was more important than the "sixth sense" and the sophistication of touch and hearing. On the monument to V. Hayuy, the founder of the education of the blind, the words addressed to a blind child are written: "You will find light in education and in work." Gajuy saw in knowledge and work the resolution of the tragedy of blindness and by this indicated the path we are now following. The age of Gaju gave education to the blind; our epoch must give them work.

The science of modern times has come closer to mastering the truth about the psychology of a blind person. The school of the Viennese psychiatrist A. Adler, which develops the method of individual psychology, i.e. social psychology personality, pointed out the significance and psychological role of an organic defect in the process of development and formation of personality. If any organ, due to morphological or functional inferiority, does not fully cope with its work, then the central nervous system and the mental apparatus take on the task of compensating for the hampered functioning of the organ. They create a psychic superstructure over an organ or function of little value, which seeks to provide the organism at a weak and threatened point.

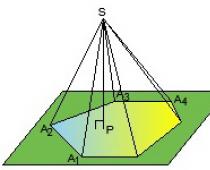

In contact with the external environment, a conflict arises, caused by a mismatch of an insufficient organ or function with their tasks, which leads to an increased possibility of disease and mortality. This conflict creates both increased opportunities and incentives for overcompensation. The defect thus becomes the starting point and the main driving force mental development of the individual. If the struggle ends in victory for the organism, then it not only copes with the difficulties created by the defect, but also rises in its development to a higher level, creating talent out of insufficiency, ability out of defect, strength out of weakness, supervalue out of low value. So, N. Saunderson, blind from birth, compiled a textbook on geometry (A. Adler, 1927). What an enormous strain his psychic powers and the tendency to overcompensate must have reached in him, brought to life by a defect in vision, so that he could not only cope with the spatial limitation that blindness entails, but also master space in higher forms, accessible to mankind only in the scientific world. thinking, in geometric constructions. Where we have much lower degrees of this process, the fundamental law remains the same. It is curious that Adler found 70% of students with visual anomalies in schools of painting and the same number of students with speech defects in schools of dramatic art (A. Adler. In the book: Heilen und Bilder, 1914, p. 21). The vocation for painting, the ability for it grew out of defects in the eye, artistic talent - from the defects of the speech apparatus that were overcome.

However, a happy outcome is by no means the only or even the most frequent result of the struggle to overcome a defect. It would be naive to think that every illness invariably ends happily, that every defect happily turns into a talent. Every fight has two outcomes. The second outcome is the failure of overcompensation, complete victory feelings of weakness, asocial behavior, the creation of defensive positions from one's weakness, turning it into a weapon, a fictitious goal of existence, in essence, madness, the impossibility of a normal mental life of a person - an escape into illness, neurosis. Between these two poles there is a huge and inexhaustible variety of different degrees of success and failure, giftedness and neurosis - from minimal to maximal. The existence of extreme points marks the limits of the phenomenon itself and gives an extreme expression of its essence and nature.

Blindness makes it difficult for a blind child to enter into life. Conflict flares up along this line. In fact, the defect is realized as a social dislocation. Blindness puts its wearer in a certain and difficult social position. Feelings of low value, insecurity and weakness arise as a result of the blind man's assessment of his position. As a reaction of the psychic apparatus, tendencies towards overcompensation develop.

They are aimed at the formation of a socially valuable personality, at gaining a position in public life. They are aimed at overcoming the conflict and, therefore, do not develop touch, hearing, etc., but capture the entire personality without a trace, starting from its innermost core; they seek not to replace vision, but to overcome and overcompensate for social conflict, psychological instability as a result of a physical defect. This is the essence of the new vision.

It used to be thought that a blind child's entire life and development would follow the line of his blindness. New law says they will go against that line. Anyone who wants to understand the psychology of the personality of a blind person directly from the fact of blindness, as directly determined by this fact, will understand it just as wrongly as one who sees only the disease in the inoculation of smallpox. It is true that the inoculation of smallpox is the inoculation of disease, but in essence it is the inoculation of superhealth. In the light of this law, all particular psychological observations of the blind are explained in their relation to the developmental lineage, to a single life plan, to the ultimate goal, to the "fifth act," as Adler puts it. Separate psychological phenomena and processes must be understood not in connection with the past, but with a focus on the future. To fully understand all the features of a blind person, we must reveal the tendencies inherent in his psychology, the germs of the future. In essence, these are the general requirements of dialectical thinking in science: in order to fully elucidate a phenomenon, it is necessary to consider it in connection with its past and future. This is the perspective of the future that Adler introduces into psychology.

Psychologists have long noted the fact that a blind man does not experience his blindness at all, contrary to the current opinion that he constantly feels himself immersed in darkness. According to the beautiful expression of A.V. Birilev, a highly educated blind man, a blind man does not see the light differently than a blindfolded sighted man. A blind man does not see the light just as a sighted person does not see it with his hand, i.e. he does not feel and does not feel directly that which is deprived of sight. “I could not directly feel my physical handicap,” testifies A.M. Shcherbina (1916, p. 10). The basis of the psyche of the blind is not an "instinctive organic attraction to the light", not the desire to "get rid of the gloomy veil", as V.G. Korolenko in the famous story "The Blind Musician". The ability to see the light for the blind has a practical and pragmatic significance, and not an instinctively organic one, i.e. the blind only indirectly, reflected, only in social consequences feels his defect. It would be a naive mistake of a sighted person to believe that we will find blindness in the psyche of a blind person or its psychic shadow, projection, reflection; in his psyche there is nothing but tendencies to overcome blindness (desires for overcompensation) of attempts to win a social position.

Almost all researchers agree, for example, that in the blind we generally find a higher development of memory than in the sighted. The last comparative study by E. Kretschmer (1928) showed that the blind have better verbal, mechanical and rational memory. A. Petzeld cites the same fact, established by a number of studies (A. Petzeld, 1925). Burklen collected the opinions of many authors who agree on one thing - in the assertion of a special power of development in the blind memory, which usually surpasses the memory of the sighted (K. Burklen, 1924). Adler would ask: why do the blind have a strong memory, that is, what is the reason for this overdevelopment, what functions in the behavior of the personality does it fulfill, what needs does it meet?

It would be more correct to say that the blind have a tendency to an increased development of memory; develop: whether it is actually very high - it depends on many complex circumstances. The trend, established with certainty in the mind of the blind, becomes perfectly explicable in the light of compensation. In order to win a position in public life, a blind person is forced to develop all his compensatory functions. The memory of the blind develops under the pressure of tendencies to compensate for the low value created by blindness. This can be seen from the fact that it develops in a completely specific way, determined by the ultimate goal of this process.

There are various and conflicting data on the attention of the blind. Some authors (K. Stumpf and others) are inclined to see an increased activity of attention in a blind person; others (Schroeder, F. Zech), and mainly teachers of the blind, who observe the behavior of students during classes, assert that the attention of the blind is less developed than that of the sighted. However, it is wrong to raise the question of the comparative development of mental functions in the blind and the sighted as a quantitative problem. It is necessary to ask not about the quantitative, but about the qualitative, functional difference between the same activity in the blind and the sighted. In what direction does the attention of a blind person develop? Here's how to ask. And here, in establishing qualitative features, everyone agrees. Just as the blind have a tendency to develop their memory in a specific way, they have a tendency to specific development attention. Or rather: both one and the other process is taken over by a general tendency to compensate for blindness and gives them both one direction. The peculiarity of the attention of a blind person lies in the special power of concentration of stimuli of hearing and touch, which sequentially enter the field of consciousness, in contrast to simultaneously, i.e. immediately entering the field of view of visual sensations, causing a quick change and dispersion of attention due to the competition of many simultaneous stimuli. When we want to collect our attention, according to K. Stumpf, we close our eyes and artificially turn into blind people (1913). In connection with this, there is also an opposite, balancing and limiting feature of attention in a blind person: complete concentration on one object until complete forgetfulness of the environment, complete immersion in the object (which we find in the sighted) cannot be in the blind; the blind man is compelled under all circumstances to maintain a certain contact with outside world through the ear, and therefore, to a certain extent, must always distribute his auditory attention to the detriment of his concentration (Ibid.).

It would be possible to show in each chapter of the psychology of the blind the same thing that we have just outlined in the examples of memory and attention. Both emotions, and feelings, and fantasy, and thinking, and other processes of the psyche of a blind person are subject to one general tendency to compensate for blindness. Adler calls this unity of the entire goal-oriented life attitude the life line - a single life plan that is unconsciously carried out in outwardly fragmentary episodes and periods and permeates them as a common thread, serving as the basis for a personality biographer. “Insofar as over time all mental functions proceed in a chosen direction, all mental processes receive their typical expression, insofar as a sum is formed tactics, aspirations and abilities that cover a defined life plan. This is what we call character "(O. Ruhle, 1926. p. 12). Contrary to Kretschmer's theory, for which character development is only a passive deployment of that basic biological type that is innately inherent in man, Adler's teaching derives and explains the structure of character and personality not from a passive unfolding of the past, but from an active adaptation to the future. Hence the basic rule for the psychology of the blind: the whole cannot be explained and understood from the parts, but its parts can be comprehended from the whole. The psychology of the blind cannot be constructed from the sum of individual features, particular deviations, individual signs of a particular function, but these features and deviations themselves become understandable only when we start from a single and whole life plan, from the blind line of the blind and determine the place and significance of each feature and individual sign in this whole and in connection with it, that is, with all other signs.

Until now, science has had very few attempts to investigate the personality of a blind person as a whole, to unravel his leitline. Researchers approached the issue for the most part in summary and studied particulars. Among such synthetic experiments, the most successful, is the work of A. Petzeld mentioned above. Its main position: in the blind, in the first place is limited freedom of movement, helplessness in relation to space, which, unlike the deaf and dumb, allows you to immediately recognize the blind. On the other hand, the rest of the powers and abilities of the blind can fully function to the extent that we cannot notice this in the deaf and dumb. The most characteristic thing in the personality of a blind person is the contradiction between relative helplessness in terms of space and the possibility through speech of complete and completely adequate communication and mutual understanding with the sighted (A. Petzeld, 1925), which fits into the psychological scheme of defect and compensation. This example is a special case of the opposition that the basic dialectical law of psychology establishes between an organically given insufficiency and mental aspirations. The source of compensation for blindness is not the development of touch or the refinement of hearing, but speech - the use of social experience, communication with the sighted. Petzeld mockingly cites the opinion of the eye doctor M. Dufour, that the blind should be made helmsmen on ships, since, due to their refined hearing, they should catch any danger in the fog. For Petzeld (1925) it is impossible to seriously seek compensation for blindness in the development of hearing or other individual functions. Based on a psychological analysis of the spatial representations of the blind and the nature of our vision, he comes to the conclusion that the main driving force of blindness compensation - approaching the social experience of the sighted through speech - has no natural limits for its development, contained in the very nature of blindness. Is there something that a blind person cannot know because of blindness, he asks, and comes to a conclusion that is of great fundamental importance for the entire psychology and pedagogy of the blind: the ability to know in a blind person is the ability to know everything, his understanding is basically the ability to to the understanding of everything (Ibid.). This means that the blind have the opportunity to achieve social value to the fullest.

It is very instructive to compare the psychology and developmental possibilities of the blind and the deaf. From a purely organic point of view, deafness is a lesser defect than blindness. A blind animal is probably more helpless than a deaf one. The natural world enters us through the eye more than through the ear. Our world is organized more like a visual phenomenon than a sound one. There are almost no biologically important functions that are affected by deafness; with blindness, spatial orientation and freedom of movement decrease, i.e. essential animal function.

So, on the biological side, the blind have lost more than the deaf. But for a person whose artificial, social, technical functions come to the fore, deafness means a much greater disadvantage than blindness. Deafness causes dumbness, deprivation of speech, isolates a person, turns him off from social contact based on speech. Deafness as an organism, as a body, has greater potential for development than blindness, but the blind as a person, as a social being; the unit is in an immeasurably more favorable position: he has speech, and with it the possibility of social usefulness. Thus, the leitline in the psychology of a blind person is corrected for overcoming the defect through its social compensation, through familiarization with the experience of the sighted, through speech. Blindness is conquered by the word.

Now we can turn to the main question outlined in the epigraph: is the blind in the eyes of science a representative of a special breed of people? If not, what are the limits, sizes and meanings of all the features of his personality? How does a blind person take part in social and cultural life? In the main, we answered this question with everything said above. In essence, it is already given in the limiting condition of the epigraph itself: if the processes of compensation were not guided by communication with the sighted and the demand to adapt to social life, if the blind man lived only among the blind, only in this case could a special type of human being be developed from him.

Neither at the end point towards which the development of a blind child is directed, nor in the very mechanism that sets in motion the forces of development, is there a fundamental difference between a sighted and a blind child. This is the most important position of the psychology and pedagogy of the blind. Every child is endowed with a relative organic inferiority in the society of adults in which he grows up (A. Adler, 1927). This allows us to consider any childhood as an age of uncertainty, low value, and any development as aimed at overcoming this state through compensation. So, the end point of development - the conquest of a social position, and the whole process of development are the same for a blind and a sighted child.

Psychologists and physiologists alike recognize the dialectical character of psychological acts and reflexes. The need to overcome, to overcome an obstacle causes an increase in energy and strength. Let us imagine a being who is absolutely adapted, encountering absolutely no obstacles to life's functions. Such a being will necessarily be incapable of development, of raising its functions and moving forward, for what will impel it to such advancement? Therefore, it is precisely in the inability of childhood that the source of enormous developmental opportunities lies. These phenomena are among those so elementary, common to all forms of behavior from the lowest to the highest, that they can by no means be considered some kind of exceptional property of the mind of the blind, his peculiarity. The opposite is true: the increased development of these processes in the behavior of a blind person is a special case. common law. Already in the instinctive, i.e. In the simplest forms of behavior, we meet with both features that we described above as the main features of the psyche of a blind person: with the purposefulness of psychological acts and their growth in the presence of obstacles. So that the focus on the future is not an exclusive property of the psyche of the blind, but is general form behavior.

I.P. Pavlov, studying the most elementary conditional connections, stumbled upon this fact in his research and described it, calling it the goal reflex. With this seemingly paradoxical expression, he wants to point out two points: 1) that these processes proceed according to the type of a reflex act; 2) that they are directed to the future, in connection with which they can be understood.

It remains to add that not only the end point and the paths of development leading to it are common for the blind and the sighted, but also the main source from which this development draws its content is the same for both - language. We have already cited Petzeld's opinion above that it is precisely language, the use of speech, that is the instrument for overcoming the consequences of blindness. He also established that the process of using speech is fundamentally the same for the blind and for the sighted: at the same time, he explained the theory of surrogate representations of F. Gitschman: "Red for the blind," he says, black and white in his understanding are the same opposites as those of a sighted person, and their significance as relations of objects is also no less ... The language of the blind, if we admit the fiction, would be completely different only in the world of the blind. Dufour is right when he says that a language created by the blind would bear little resemblance to ours, But we cannot agree with him when he says: "I saw that in essence the blind think in one language, but speak friend"" (A. Petzeld, 1925).

So, the main source from which compensation draws its strength is again the same for the blind and the sighted. Considering the process of raising a blind child from the point of view of the doctrine of conditioned reflexes, we came to the following in due time: from the physiological point of view, there is no fundamental difference between the upbringing of a blind child and a sighted child. Such a coincidence should not surprise us, since we should have expected in advance that the physiological basis of behavior would reveal the same structure as the psychological superstructure. So from two different ends we come to the same thing.

The coincidence of physiological and psychological data should further convince us of the correctness of the main conclusion. We can formulate it this way: blindness as an organic inferiority gives impetus to compensation processes, leading to the formation of a number of features in the psychology of the blind and restructuring all separate, particular functions from the angle of the main life task. Each individual function of the mental apparatus of a blind person presents its own characteristics, often very significant in comparison with the sighted; left to itself, this biological process of formation and accumulation of features and deviations from the normal type aside, in the case of a blind man living in a world of the blind, would inevitably lead to the creation of a special breed of people. Under the pressure of the social demands of the sighted, the processes of overcompensation and the use of speech, which are the same for the blind and the sighted, the whole development of these features develops in such a way that the personality structure of the blind as a whole tends to achieve a certain normal social type. With partial deviations, we can have a normal personality type in general. The merit of establishing this fact belongs to Stern (W. Stern, 1921). He accepted the doctrine of compensation and explained how strength is born from weakness, dignity from shortcomings. In a blind person, the ability to distinguish by touch is refined compensatory - not through a real increase in nervous excitability, but through exercises in observing, evaluating and understanding differences. Similarly, in the field of the psyche, the low value of one of some properties can be partially or completely replaced by the enhanced development of another. Weak memory, for example, is balanced by the development of understanding, which is put at the service of observation and memorization; weakness of the will and lack of initiative can be compensated by suggestibility and a tendency to imitate, etc. A similar view is reinforced in medicine: the only criterion for health and disease is the expedient or inappropriate functioning of the whole organism, and partial deviations are evaluated only insofar as they are compensated or not compensated other bodily functions. Against the "microscopically refined analysis of abnormalities" Stern puts forward the position: particular functions can represent a significant deviation from the norm, and yet the person or the organism as a whole can be completely normal. A child with a defect is not necessarily a defective child. From the outcome of the compensation, i.e. the degree of his defectiveness and normality depends on the final formation of his personality as a whole.

K. Byurklen outlines two main types of the blind: one seeks to minimize and nullify the abyss that separates the blind from the sighted; the other, on the contrary, emphasizes differences and requires the recognition of a special form of personality that corresponds to the experiences of the blind. Stern believes that this opposition is also of a psychological nature; both blind people probably belong to two different types (K. Burklen, 1924). Both types in our understanding mean two extreme outcomes of compensation; the success and failure of this basic process. That in itself this process, regardless of the bad outcome, does not contain anything exceptional, inherent only in the psychology of the blind, we have already said. We will only add that such an elementary and basic function for all forms of activity and development as exercise is considered by modern psychotechnics as a special case of compensation. Therefore, it is equally wrong to classify a blind person as a special type of person on the basis of the presence and dominance of this process in his psyche, as it is to turn a blind eye to those profound features that characterize this general process in the blind. V. Steinberg rightly disputes the walking slogan of the blind: "We are not blind, we just cannot see" (K. Burklen, 1924, p. 8).

All functions, all properties are restructured under the special conditions of the development of the blind: it is impossible to reduce all differences to one point. But at the same time, the personality as a whole of a blind person and a sighted person can belong to the same type. It is rightly said that the blind understand the world of the sighted more than the sighted understand the world of the blind. Such an understanding would be impossible if the blind person did not approach the type of a normal person in development. Questions arise: what explains the existence of two types of the blind? Is it due to organic or psychological reasons? Doesn't this refute the above propositions or, according to at least, does it introduce significant restrictions and amendments to them? In some blind people, as Shcherbina beautifully described, a defect is organically compensated, “a kind of second nature is created” (1916, p. 10), and they find in life, with all the difficulties associated with blindness, a peculiar charm that they cannot refuse. would agree for any personal benefits. This means that in the blind the mental superstructure so harmoniously compensated for their low value that it became the basis of their personality; to give it up would mean for them to give up themselves. These cases fully confirm the doctrine of compensation. As for cases of failure of compensation, here the psychological problem turns into a social problem: do healthy children of the vast masses of humanity achieve everything that they could and should have achieved in terms of psychophysiological structure?

Our review is over; we are on the coast. It was not our task to shed any light on the psychology of the blind; we just wanted to point out center point problems, the knot in which all the threads of their psychology are tied. We found this knot in the scientific idea of compensation. What separates the scientific conception of this problem from the prescientific one? If the ancient world and Christianity saw the solution of the problem of blindness in the mystical powers of the spirit, if the naive biological theory saw it in automatic organic compensation, then the scientific expression of the same idea formulates the problem of the solution of blindness as social and psychological. To a superficial glance, it may easily seem that the idea of compensation brings us back to the Christian-medieval view of the positive role of suffering, the weakness of the flesh. In fact, two more opposing theories cannot be imagined. The new teaching positively evaluates not blindness in itself, not a defect, but the forces contained in it, the sources for overcoming it, and incentives for development. Not simply weakness, but weakness as a path to strength is marked here with a positive sign. Ideas, like people, are best known by their deeds. scientific theories should be judged by the practical results to which they lead.

What is the practical side of all the theories mentioned above? According to the correct remark of Petzeld, the reassessment of blindness in theory created in practice Homer, Tiresias, Oedipus as living evidence of the boundlessness and infinity of the development of a blind person. Ancient world created the idea and real type of the great blind man. In the Middle Ages, on the contrary, the idea of underestimating blindness was embodied in the practice of charity for the blind. According to the true German expression: "Verehrt - ernahrt" - antiquity revered the blind, the Middle Ages fed them. Both were expressions of the inability of pre-scientific thinking to rise above the one-sided concept of the education of blindness: it was recognized as either a strength or a weakness, but the fact that blindness is both, i.e. weakness leading to strength - this thought was alien to that era.

Start scientific approach to the problem of blindness was marked in practice by an attempt to create a systematic education of every blind person. This was a great era in the history of the blind. But Petzeld said correctly: “The very fact that it was possible to quantify the question of the viability of the remaining senses in a blind person and to study them experimentally in this sense points in principle to the same nature of the state of the problem that was inherent in antiquity and the Middle Ages” (A. Petzeld, 1925, p. 30). In the same era, Dufour advised making helmsmen out of the blind. This era tried to rise above the one-sidedness of antiquity and the Middle Ages, for the first time to combine both ideas about blindness - hence the necessity (out of weakness) and the possibility (out of strength) of the education of the blind; but then they failed to connect them dialectically and represented the connection of strength and weakness purely mechanically.

Finally, our era understands the problem of blindness as a socio-psychological one and has in its practice three types of weapons to combat blindness and its consequences. True, in our time, thoughts about the possibility of a direct victory over blindness often emerge. People do not want to part with that ancient promise that the blind will see. Quite recently we have witnessed the resurrection of deceived hopes that science will restore sight to the blind. In such outbursts of unfulfilled hopes, in essence, dilapidated remnants of ancient times and a thirst for a miracle come to life. They do not contain the new word of our epoch, which, as has been said, has at its disposal three kinds of weapons: social prevention, social education, and social labor of the blind—these are the three practical pillars on which the modern science of the blind man stands. All these forms of struggle must be completed by science, bringing to the end what is healthy that was created in this direction by previous epochs. The idea of preventing blindness must be instilled in the vast masses of the people. It is also necessary to eliminate the isolated and disabled education of the blind and to erase the line between the special and normal schools: the education of a blind child must be organized as the education of a child capable of normal development; education should really create a normal, socially valuable person out of a blind person and eradicate the word and the concept of "defective" in application to the blind. And finally, modern science should give the blind the right to social labor not in its humiliating, philanthropic and invalid forms (as it has been cultivated until now), but in forms that correspond to the true essence of labor, the only one capable of creating the necessary social position for the individual. But is it not clear that all these three tasks set by blindness are by nature social tasks and that only a new society can finally solve them? The new society creates a new type of blind person. The first stones of a new society are now being laid in the USSR and, therefore, the first features of this new type are taking shape.

Lev Semenovich Vygotsky (1896-1934) Russian and Soviet psychologist, founder of the cultural-historical school in psychology.

L. S. Vygotsky

blind child

They (the blind. - L.V.) develop such features that we cannot notice in the sighted, and it must be assumed that in the case of exclusive communication between the blind and the blind, without any intercourse with the sighted, a special breed of people could arise,

K. Bürklen*

Article

On the topic:

« Views of Vygotsky L.S. on the deviating development of the child "

Prepared by the educator GBDOU No. 83

Danogueva R.A.

“Humanity will conquer sooner or later both blindness and deafness and dementia, but much sooner it will conquer them socially and pedagogically than medically and biologically.”

L. S. Vygotsky

The main provisions of the concept of L. S. Vygotsky

L.S. Vygotsky formulated the general patterns of mental development. Lev Semenovich argued that a normal and abnormal child develops according to the same laws. Along with the general laws of L.S. Vygotsky also noted the peculiarity of the development of an abnormal child, which consists in the divergence of the biological and cultural processes of development. The merit of L.S. Vygotsky in that he pointed out the fact that the development of a normal and abnormal child is subject to the same laws and goes through the same stages, but the stages are extended in time and the presence of a defect gives specificity to each variant of abnormal development. In addition to broken functions, there are always preserved functions. Corrective work should be based on preserved functions, bypassing affected functions. L.S. Vygotsky formulates the principle corrective work bypass principle.

For the practice of working with children, Vygotsky's concept "On the developmental nature of education" takes place. Education should lead to development, and this is possible if the teacher is able to determine the "zone of actual development" and the "zone of proximal development".

L.S. Vygotsky was one of the first to draw attention to the painful nature of these trainings. The scientist advocated such a principle of correctional and educational work, in which the correction of the shortcomings of the cognitive activity of abnormal children would be dissolved in the entire process of education and upbringing, carried out in the course of play, educational and labor activities. Developing in child psychology the problem of the relationship between learning and development, L.S. Vygotsky came to the conclusion that learning should precede, run ahead and pull up, lead the development of the child. Learning must lead to development. Such an understanding of the correlation of these processes instilled in him the need to take into account both the current level of development of the child and his potential. Vygotsky defined the current level of mental development as the stock of knowledge and skills that a child had formed by the time of the study on the basis of already mature mental functions.

A huge contribution to the development of correctional pedagogy was made by the scientist-psychologist L.S. Vygotsky. The establishment of the unity of the psychological patterns of the development of the child in normal and pathological conditions allowed L.S. Vygotsky to substantiate the general theory of the development of the personality of an abnormal child. In all the works of L.S. Vygotsky in the field of correctional pedagogy - the idea of social conditioning of specifically human higher mental functions was carried out.

The influence of the ideas of L. S. Vygotsky on the development of the domestic theory and practice of special education

The founder of modern domestic psychology and defectology L.S. Vygotsky made a great contribution to the study of the personality of an abnormal child, to substantiating the problem of compensation for a defect in the process of specially organized upbringing and education of abnormal children. He argued that the blind and deaf feel their inferiority not biologically, but socially. “It is not the defect in itself that decides the fate of the individual, but his social consequences, its socio-psychological organization”. That is why “the speaking deaf-mute, the working blind, the participants common life in its entirety, they themselves will not feel inferiority and will not give a reason for this to others. It is in our hands to make sure that a deaf, blind and feeble-minded child is not handicapped. Then the word itself disappears, a sure sign of our own defect.”

The position of L.S. Vygotsky that “a child with a defect is not yet a defective child”, “that in itself blindness, deafness, etc., particular defects do not yet make their carrier defective”, “that “substitution and compensation” as a law, arise in the form of aspirations where there is a defect ”played a big role in the development of the theory and practice of modern deaf pedagogy. It serves as the basis for the inexhaustible humanism and optimism of domestic defectologists. This is evidenced by the fact that in the conditions of modern reality, unlimited all-round development of deaf children is possible.

Aim high social education for deaf children, its achievement in the real process of education presupposes a high quality of education. More L.S. Vygotsky ardently defended the need for social special education of abnormal children, pointed out that the special education of abnormal children requires “special pedagogical techniques, special methods and techniques,” and also that “only the highest scientific knowledge of this technique can create a real teacher in this area". He emphasized that “we must not forget that it is necessary to educate not the blind, but the child first of all. To educate a blind and deaf person means to educate blindness and deafness, and from the pedagogy of childhood defects to turn it into a defective pedagogy. In these thoughts of the deepest meaning, L.S. Vygotsky contains the quintessence of specially organized education for deaf children.

The educator must be a defectologist-deaf teacher with a higher education in surodopedagogics. Based on deep knowledge of general and special pedagogy and psychology, he must, focusing on the real possibilities of the deaf, in accordance with the goal of social education, plan work. The deaf educator must act competently, applying the correct, effective methods educational work. He must see in a deaf pupil, first of all, a personality. The personality of a deaf educatee should become a kind of geometric locus of points of specially organized upbringing and education. The educator as the subject of education in his work is constantly faced with a complex of feelings, moods, experiences of pupils and his own. Deafness naturally evokes feelings of pity and compassion.

The great humanist, L.S. Vygotsky, saw the highest manifestation of humanism not in the fact that the educator, the teacher showed indulgence and concessions, focusing on a defect in their work, but, on the contrary, that they created difficulties within reasonable limits for deaf children in the process of their upbringing and education, taught to overcome these difficulties, and thus developed the personality, its healthy forces. Speaking about special education, he emphasized: “Tempering and courageous ideas are needed here. Our ideal is not to cover the sore spot with cotton wool and protect it by all means from bruises, but to open the widest path to overcome the defect, its overcompensation. To do this, we need to assimilate the social orientation of these processes.”

Ideas L.S. Vygotsky about the ways of developing special education and training of deaf children were further developed in the theory and practice of domestic deaf pedagogy. The question of choosing the right paths, appropriate content effective forms and methods of educational work in the school for the deaf is one of the central problems of an integrated approach to education. Ideas L.S. Vygotsky about the features of the mental development of the child, about the zones of actual and immediate development, the leading role of training and education, the need for a dynamic and systematic approach to the implementation of corrective action, taking into account the integrity of personality development, are reflected and developed in theoretical and experimental studies of domestic scientists, as well as in practice different types schools for abnormal children. Much attention in his works L.S. Vygotsky paid attention to the problem of studying abnormal children and their correct selection in special institutions. Modern principles of selecting children are rooted in the concept of L.S. Vygotsky.

Ideas L.S. Vygotsky about the features of the child's mental development, about the zones of actual and immediate development, the leading role of training and education, the need for a dynamic and systematic approach to the implementation of corrective action, taking into account the integrity of personality development, and a number of others were reflected and developed in theoretical and experimental studies of domestic scientists, and also in the practice of different types of schools for abnormal children.

In the early 30s. L.S. Vygotsky worked fruitfully in the field of pathopsychology. One of the leading provisions of this science, contributing to the correct understanding of the abnormal development of mental activity, according to well-known experts, is the position on the unity of intellect and affect. L.S. Vygotsky calls it the cornerstone in the development of a child with a intact intellect and a mentally retarded child. The significance of this idea goes far beyond the problems in connection with which it was expressed. Lev Semenovich believed that "the unity of intellect and affect ensures the process of regulation and mediation of our behavior."

L.S. Vygotsky took a new approach to the experimental study of the basic processes of thinking and to the study of how higher mental functions are formed and how they disintegrate in pathological states of the brain. Thanks to the work carried out by Vygotsky and his collaborators, the decay processes received their new scientific explanation. The theoretical and methodological concept developed by L.S. Vygotsky, ensured the transition of defectology from empirical, descriptive positions to truly scientific foundations, contributing to the formation of defectology as a science.

Such well-known defectologists as E.S. Bein, T.A. Vlasova, R.E. Levina, N.G. Morozova, Zh.I. Shif, who was lucky enough to work with Lev Semenovich, assessed his contribution to the development of theory and practice in the following way: "His works served scientific basis construction of special schools and theoretical substantiation of the principles and methods for studying the diagnosis of difficult children. Vygotsky left a legacy of enduring scientific significance, which entered the treasury of Soviet and world psychology, defectology, psychoneurology and other related sciences. Vygotsky research in all areas of defectology are still fundamental in the development of problems of development, education and upbringing of abnormal children. The outstanding Soviet psychologist A.R. Luria in scientific biography, paying tribute to his mentor and friend, wrote: "It would not be an exaggeration to call L. S. Vygotsky a genius."

L.S. Vygotsky is a Russian psychologist, the creator of the cultural-historical concept of the development of higher mental functions. He dealt with the problems of defectology in the laboratory of psychology of abnormal childhood he created, formed new theory development of the abnormal child. In the last stage of his work, he studied the relationship between thinking and speech, the development of meanings in ontogenesis, and egocentric speech. Introduced the concept of the zone of proximal development. He had a significant impact on both domestic and world thought. To this day, the ideas of Vygotsky and his school form the basis of the scientific worldview of thousands of real professionals, in his scientific papers new generations of psychologists draw inspiration not only in Russia, but all over the world.

State and current problems of education and upbringing of children with developmental problems in Russia

Democratic transformations in society and evolutionary development systems of special education contributed to the emergence and implementation of the ideas of integrated education and training of children with developmental disabilities together with normally developing peers. At present, the integrated upbringing and education of children has expanded significantly in the Russian Federation. However, it is necessary to give this process an organized character, providing each child with developmental disabilities with early age an accessible and useful form of integration for its development. The introduction of integrated education and training into the practice of preschool educational institutions allows expanding the coverage of children with the necessary correctional and pedagogical and medical and social assistance, bringing it as close as possible to the place of residence of the child, providing parents (legal representatives) with advisory support, and preparing society for the acceptance of a person with disabilities. opportunities.

The development of integrated education and training creates the basis for building a qualitatively new interaction between the mass and. special education, overcoming barriers and making the boundaries between them transparent. At the same time, each child with developmental disabilities receives the specialized psychological and pedagogical assistance and support he needs. It is important to pay special attention to the integration of young children, which contributes to the achievement of a child with disabilities equal or close in age to the level of general and speech development and allows him to join the environment of normally developing peers at an earlier stage of his development.

In system preschool education In Russia, this form of education and upbringing of children with developmental disabilities should take into account modern Russian socio-economic conditions, the peculiarities of the domestic education system and completely exclude the "mechanical copying" of foreign models. In addition, integration should not be carried out spontaneously, it is possible only if preschool educational institutions have the appropriate material, technical, software, methodological and staffing. Only the combination of these conditions provides a full-fledged, well-organized system of integrated education and training of children with developmental disabilities. In this regard, the most adequate conditions for carrying out purposeful work on the integrated upbringing and education of preschoolers have been created in a preschool educational institution of a combined type.

A preschool educational institution of a combined type can organize integrated education and training for a certain category of pupils, for example, joint education and education of normally hearing children and children with hearing impairments, children with normal and impaired vision, normally developing and children with mental retardation, etc. In each preschool of a combined type, it is advisable to provide conditions for the provision of corrective assistance to children with complex spill disorders. Thus, even in a small locality(especially in rural areas), which has only three to five preschool educational institutions, the upbringing and education of almost all categories of preschoolers can be organized, which leads to an increase in the coverage of needy children with specialized correctional and pedagogical assistance and makes preschool education more accessible.

In a preschool educational institution of a combined type, general developmental, compensatory, health-improving groups and various combinations can be organized. However, at present, in the transitional period of the development of the system of special education, due to socio-economic changes in society, as well as the constantly increasing number of children with developmental disabilities, the problem of finding new, effective forms of providing corrective psychological and pedagogical assistance to needy children becomes particularly relevant. One of these forms is the organization in the preschool educational institution of a combined type of mixed groups, where normally developing children and children with certain developmental disabilities are brought up and trained at the same time. Mixed groups are financed according to the standards corresponding to the standards for financing groups of a compensating type.

The recruitment of a mixed group is carried out at the request of the parents and on the basis of the conclusion of the psychological-pedagogical and medical-pedagogical commission. At the same time, the total occupancy of the group is reduced, two thirds of the group are pupils with a level of psychophysical development in accordance with the age norm, and one third of the pupils are children with one or another deviation or young children who do not have pronounced primary deviations in development, but lag behind the age limit. norms.

It is not recommended to create mixed groups for children with speech disorders. This is due to the fact that this category of children is already practically in conditions of integration. In addition, the system of special speech therapy assistance provides for classes with a speech therapist in a children's clinic, in a speech center of an educational institution, as well as short-term training of children with phonetic and phonemic speech disorders in speech therapy groups of preschool educational institutions for 0.5-1 year.

The occupancy of the mixed group depends on the nature of the primary deviation in development and the age of the child. The overall occupancy of the mixed group is decreasing.

Content educational process in a mixed group, it is determined by the program of preschool education and special programs, taking into account the individual characteristics of the pupils. The teaching staff is independent in choosing programs from a set of variable general developmental and correctional programs. An individual development program is drawn up for each pupil of the group.

To organize the work of a mixed group, the position of a defectologist teacher is introduced into the staff of the preschool educational institution. At the end of each year of study, the psychological-pedagogical and medical-pedagogical commissions, based on the results of a survey of the pupils of the group, make recommendations on further forms of education for each child with developmental disabilities.

Carrying out targeted work on the integration of children with developmental disabilities in a team of healthy peers and, in connection with this, the possible expansion of the network of combined preschool does not mean the abolition of previously created preschool educational institutions compensatory type. Moreover, such preschool educational institutions can take an active part in the integrated upbringing and education of that part of children with developmental disabilities, which is also in conditions of full integration. These children can receive qualified correctional assistance through short stay groups.

Vygotsky was able to identify the leading trends in the prevention and overcoming of abnormal childhood, to identify, systematize and link them with the general patterns of development of the individual and society. He formulated the new tasks of special pedagogy and the special school, the main theoretical prerequisites for the restructuring of work in the field of abnormal childhood. Their essence boiled down to linking the pedagogy of defective childhood (surdo-, typhlo-, oligo-, etc. pedagogy) with general principles and methods of social education, to find a system in which it would be possible to organically link special pedagogy with the pedagogy of normal childhood.

The idea of integration, the relationship of general and special psychological and pedagogical issues runs through all the work of the scientist. He identified and formulated the basic laws of the mental development of the child: the law of the development of higher mental functions, the law of uneven child development, the law of metamorphosis in child development and others. He put forward the idea of the uniqueness of the development of the personality of an abnormal child, which is formed, like in an ordinary child, in the process of interaction of biological, social and pedagogical factors.

L.S. Vygotsky developed and scientifically substantiated the foundations of the social rehabilitation of an abnormal child. In contrast to curative pedagogy, which then relied on psychological orthopedics and sensory education, he developed social pedagogy that removes negative social layers in the process of forming a child's personality in play, learning, work and other activities.

They proposed a dynamic approach to the defect. He believed that the symptom is not a sign, not the root cause of the abnormal development of the child, but the result, a consequence of the peculiarity of its development, as a rule, complex pathological processes of an etiological and anatomical-clinical nature are hidden behind it.

Vygotsky developed the doctrine of the primacy and secondary nature of a defect, the social nature of a secondary defect, substantiated the idea of the unity of intellect and affect; thinking, like action, has a motivational basis and cannot develop in abstract conditions. He formulated the concept of the zone of proximal and actual development of the child, revealing the relationship between mental development and learning, where learning is the driving force of development.

He actively developed the idea of the compensatory capabilities of the organism of an abnormal child. He considered the starting point in correctional and pedagogical work with abnormal children to be the state of the child's body that was the least affected or not affected by it. Based on the healthy, positive, and you should work with the child, - L.S. Vygotsky.

Family education in the system of rehabilitation work with children with disabilities and developmental disabilities

Family upbringing is the upbringing of children carried out by parents or persons replacing them (relatives, guardians).

Family education of children with hearing impairment. The most severe consequence of complete or partial hearing loss is the absence or underdevelopment of speech. Therefore, if a deaf or hard of hearing child is brought up in a family, special attention should be paid to the formation of his verbal speech - to teach him to understand the speech addressed to him, to express his desires, requests, etc. Work on the formation of verbal speech should begin immediately after it is established that speech does not develop independently. In order to understand to the child that all objects have their own name, they write from the name on the plate in large block letters and attach them to the corresponding objects. To understand the speech of others, the child is taught to look into the face of the speaker "read from the lips." The child imitates the movements of the speaker's lips - reflectively repeats the speech addressed to him. With the help of special techniques, parents themselves can teach children to pronounce sounds, words, phrases. To obtain the necessary instructions, you should contact specialists - deaf teachers and speech therapists. To develop the remnants of hearing, it is necessary to use sounding and musical toys, and when addressing the child, speak loudly in his ear. It is useful to conduct classes with the child on the development of speech, counting, on the development and use of hearing remnants several times a day for 10-15 minutes. Children should be engaged in modeling, drawing, designing, etc. it is necessary to teach children to climb, jump, run, walk along the drawn lines, since children with hearing impairment often have impaired motor skills. One of the features of raising a deaf child is teaching him to silent actions: the ability to close the door without knocking, put chairs, quietly leave the table, walk without shuffling his feet, etc. It is very important that such a child is not isolated from his hearing peers. To do this, you need to help the child enter the team of normally hearing children, tell them how to talk with the deaf, and prevent possible conflicts due to an incorrect attitude towards a child with a hearing impairment.

Family education of children with visual impairment. As soon as a blind child learns to walk, one should not protect him from independent movements. You need to teach him to walk and run around the room, focus on the voice of a person and the sound of a rattle. Furniture must be removed to avoid injury. Then the child gets acquainted with the layout of the rooms in the house, with the organization of the yard and learns to move independently around the room, in the yard and on the nearest street. First, he walks holding the hand of an adult, then next to or in front of an adult. A blind child, like a sighted child, constantly strives to move, to perform some kind of activity, but the lack of vision does not allow him to see the movements of other people, and the natural need to move begins to manifest itself in rocking the torso, waving his arms, bouncing in one place, etc. the slowness of the movements of the blind instills in him the skills of orientation and self-service, to develop the senses, and expands his ideas about others. Cognition of the surrounding world is carried out with the proper education of the senses. You can teach a blind man to understand with the help of hearing to determine the sound of various types of transport, to distinguish between the voices of birds and animals, the murmur of a stream, etc. sounds. Hands replace eyes for the blind. Therefore, for the development of touch, it is necessary to teach the blind to feel objects by naming their parts. The speech of a blind person develops in the process of normal communication with others, a blind child must be told fairy tales, he must listen to children's programs on the radio; it is necessary to teach the child to answer questions correctly, to retell what was read aloud. New words encountered in the text should be explained to the child, while at the same time he can feel the corresponding object. The child is taught to talk about objects familiar to him, about his games, completed tasks. With such a concrete basis, his speech will become richer, more consistent and more accurate. The outlook and knowledge of a blind child expands with a purposeful acquaintance with seasonal changes in nature. Of particular importance for his development and his knowledge of reality are toys, when choosing which you need to pay attention to the fact that they do not contain details that distort the shape of the object, typical features of the object stand out. It is useful to use voiced toys, and for children with residual vision - colored toys. Representation, memory, attention of the child develops in comparative games. Sculpting, designing, applique,they serve as a means of developing the hand, touch and clarifying ideas about form and proportions.

Family education W.O. children, should mainly be based on labor education, which begins with solving the simplest tasks of self-service, helping other family members. No less important is the systematic development of basic hygiene skills, as well as polite, cultural behavior in the family, on the street, in in public places. Of great importance is the regular exercise with the child, developing it cognitive activity: observation of objects and phenomena surrounding nature, drawing, modeling, reading available books, exercises for the development of speech. Parents U.O. children, it is necessary to constantly maintain contact with doctors (psychoneurologist) regarding the implementation of recreational activities. From the moment W.O. child to school, it is necessary to carry out work in the family to consolidate the knowledge and skills acquired at school.

The upbringing of an abnormal young child is carried out mainly in the process of caring for him. Parents teach him to be independent, guide the development of his movements and speech. Raising a child to school age- this is physical, mental, moral, aesthetic education. It is very important to prepare a preschooler for school, it is necessary that he have certain self-service skills, be able to behave in a team, fulfill the requirements of elders, and acquire a certain range of ideas. If the child attends special ds must comply with uniform requirements in the family and in the preschool educational institution. Family education of school age is carried out in close contact with the school.

defect structure. Primarily due to developmental disorders, secondary deviation in development

A defect is a physical or mental deficiency that entails deviations from normal development.

According to their origin, defects are divided into congenital and acquired. The causes of defects that cause abnormal development are very diverse.

The concept of primary and secondary defects was introduced by L.S. Vygotsky.

Primary defects arise as a result of organic damage or underdevelopment of any biological system(analyzers, higher departments brain, etc.) due to the influence of pathogenic factors.

Secondary - have the character of mental underdevelopment and violations of social behavior, not directly arising from the primary defect, but caused by it (speech impairment in the deaf, impaired perception and spatial orientation in the blind, etc.). The further the existing violation is separated from the biological basis, the more successfully it lends itself to psychological and pedagogical correction.

In the process of development, the hierarchy between primary and secondary, biological and socially determined disorders changes. If on early stages the main obstacle to training and education is an organic defect, i.e. the direction of secondary underdevelopment "from the bottom up", then in the case of untimely started correctional and pedagogical work or in its absence, secondary phenomena of mental underdevelopment, as well as inadequate personal attitudes caused by failures in various types of activity, often begin to take a leading place in the formation of negative attitudes towards oneself, the social environment and the main activities. Extending to an ever wider range of psychological problems, secondary underdevelopment begins to have a negative impact on more elementary mental functions, i.e. the direction of pathogenic influence begins to go "from top to bottom".

middle group

Ball toss game

"Whose house? »

or “Who lives where? » Who is in the den, who is in the hole? Call me soon! "

Purpose: to consolidate children's knowledge about the dwellings of animals, insects. Consolidation of the use in the speech of children of the grammatical form of the prepositional case with the preposition "in".

Game progress. Throwing the ball to each child in turn, the speech therapist asks a question, and the child, returning the ball to the speech therapist, answers.

Option 1. Speech therapist: Children: Who lives in a hollow? Squirrel. Who lives in the birdhouse? Starlings. Who lives in the nest? Birds: swallows, cuckoos, jays, etc. Who lives in the booth? Dog Who lives in the beehive? Bees Who lives in a hole? A fox. Who lives in the lair? Wolf Who lives in a lair? Bear

Option 2. Speech therapist: Where does the bear live? Where does the wolf live? Children: In the den. In the lair.

Option 3. Work on the correct construction of the proposal. Children are invited to give a full answer: "The bear lives in a den."

ball game

"Say kindly"

Catch a small ball, and caress it with a word.

Purpose: to consolidate the ability to form nouns with the help of diminutive - affectionate suffixes, the development of dexterity, speed of reaction.

Game progress. The speech therapist, throwing the ball to the child, calls the first word (for example, a ball, and the child, returning the ball, the speech therapist; calls the second word (ball). Words can be grouped according to the similarity of endings. Table - table, key - key. Hat - slipper, squirrel - squirrel A book is a little book, a spoon is a spoon. A head is a head, a picture is a picture. Soap is a soap, a mirror is a mirror. A doll is a doll, a beet is a beetroot. A braid is a pigtail, water is water. A beetle is a bug, an oak is an oak. Cherry - cherry, tower - turret. Dress - dress, armchair - armchair. Feather - feather, glass - glass. Clock - watch.

ball game

"Animals and their babies"

Human children Know all the animals in the world.

Purpose: fixing the name of baby animals in the speech of children, consolidating word-formation skills, developing dexterity, attention, memory.

Game progress. Throwing the ball to the child, the adult names an animal, and the child, returning the ball to the speech therapist, names the cub of this animal. Basic movements: throwing the ball with a hit on the floor, throwing the ball; rolling the ball while sitting on the carpet. Words are grouped into three groups according to the way they are formed. The third group requires remembering the names of the cubs.

Group 1. tiger - lion - elephant - deer - elk - fox -

Group 2. in a bear - a teddy bear in a camel - a camel in a wolf - a wolf cub in a hare - a hare in a rabbit - a rabbit in a squirrel - a squirrel in a cow - a calf in a horse a foal in a pig - a pig in a sheep - a lamb in a chicken - a chicken in a dog - a puppy

Group 3. - tiger cub - lion cub - elephant cub - deer elk - fox cub

Senior group

"Cheerful tongue"

Target: to develop the mobility of the organs of articulation, to form the necessary articulatory pattern for the pronunciation of hissing sounds.

Stroke: the child is invited to play with a cheerful tongue and perform articulation exercises necessary to prepare for staging hissing sounds

"How Pinocchio went for mushrooms"

Target: prepare the articulatory apparatus for staging hissing sounds.

Stroke: the teacher explains to the child that Pinocchio went to the forest for hornbeams. To get to the forest, the child needs to help him overcome various obstacles (for example, build a "bridge" across the river, ride a "horse", collect "mushrooms", etc.). the child performs precise articulatory movements.

3. "Football"

Target:

Stroke: children sit at the table opposite each other. On the table, the teacher puts "collars". The task of the children is to drive the tennis ball into the opponent's goal with an air stream, to ensure that the children do not puff out their cheeks.

4. "The biggest soap bubble"

Target: develop a smooth, long, directed exhalation necessary for the pronunciation of hissing sounds.

Stroke: Soap bubbles are handed out to children. The task of each child is to inflate the biggest soap bubble. Follow the long, smooth exhalation.

5. "Traffic light"

Target: distinguish a sound from a number of other sounds, against the background of a word.

Stroke: children are given green and red signal cards. If in the series of sounds pronounced by the teacher, the children hear a given hissing sound, then they raise a green signal, if other sounds, then a red signal. The word game is played in the same way.

preparatory group

Game "Count to 5"

Task: agreement of a noun with a numeral and an adjective:

Example: 1 small snowdrop, 2 small snowdrops, 5 small snowdrops, etc.