Presented in a concise and accessible form full course disciplines, highlights the most important modern concepts of the sciences of inanimate and living nature. It is an updated and revised version. study guide recommended by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation for studying the course "Concepts modern natural science". For undergraduate students, undergraduates, graduate students and teachers of the humanities, for teachers of secondary schools, lyceums and colleges, as well as for a wide range of readers interested in various aspects of natural science.

* * *

The following excerpt from the book Concepts of modern natural science (A. P. Sadokhin) provided by our book partner - the company LitRes.

Chapter 1. Science in the context of culture

1.1. Science as part of culture

Throughout their history, people have developed many ways of knowing and mastering the world around them. Among them, one of the most important places is occupied by science, the main purpose of which is the description, explanation and prediction of the processes of reality that constitute the subject of its study. In the modern sense, science is seen as:

Supreme form human knowledge;

Social institution, consisting of various organizations and institutions engaged in obtaining new knowledge about the world;

System of developing knowledge;

Way of knowing the world;

A system of principles, categories, laws, techniques and methods for obtaining adequate knowledge;

Element of spiritual culture;

The system of spiritual activity and production.

All the given meanings of the term "science" are legitimate. But this ambiguity also means that science is complex system designed to give a generalized holistic knowledge about the world. At the same time, this knowledge cannot be disclosed by any one separate science or a set of sciences.

To understand the specifics of science, it should be considered as part of a culture created by man, compared with other areas of culture.

A specific feature of human life is the fact that it proceeds simultaneously in two interrelated aspects - natural and cultural. Initially, a person is a living being, a product of nature, however, in order to exist comfortably and safely in it, he creates an artificial world of culture inside nature, a “second nature”. Thus, a person exists in nature, interacts with it like a living organism, but at the same time “doubles” the outside world, developing knowledge about it, creating images, models, assessments, household items, etc. It is this kind of material-cognitive activity of a person and constitutes the cultural aspect of human existence.

Culture finds its embodiment in the objective results of activity, ways and methods of human existence, in various norms of behavior and various knowledge about the world around. The whole set of practical manifestations of culture is divided into two main groups: material and spiritual values. Material values form material culture, and the world of spiritual values, including science, art, religion, forms the world of spiritual culture.

Spiritual culture covers the spiritual life of society, its social experience and results, which appear in the form of ideas, scientific theories, artistic images, moral and legal norms, political and religious views and other elements of the human spiritual world.

inalienable integral part culture is a science that determines many important aspects of the life of society and man. It, like other spheres of culture, has its own tasks that distinguish them from each other. Thus, the economy is the foundation that ensures all the activities of society; it arises on the basis of a person's ability to work. Morality regulates relations between people in society, which is very important for a person who cannot live outside society and must limit his own freedom in the name of the survival of the entire team. Religion arises from a person's need for consolation in situations that cannot be resolved rationally (for example, the death of loved ones, illness, unhappy love, etc.).

The task of science is to obtain objective knowledge about the world, the knowledge of the laws by which the world around us functions and develops. Possessing such knowledge, it is much easier for a person to transform this world, to make it more convenient and safe for himself. Thus, science is a sphere of culture, most closely associated with the task of directly transforming the world, increasing its convenience for man.

In accordance with the transformative role of science, its high authority was formed, which was expressed in the appearance scientism - a worldview based on faith in science as the only force to solve all human problems. Scientism declared science to be the pinnacle of human knowledge, while it absolutized methods and results natural sciences, denying scientific character social and humanitarian knowledge as having no cognitive value. From such ideas gradually arose the idea of two unrelated cultures - the natural sciences and the humanities.

In contrast to scientism in the second half of the twentieth century. formed an ideology antiscientism, considering science as a dangerous force leading to the death of mankind. Its supporters are convinced of the limited possibilities of science in solving fundamental human problems and deny science positive influence to culture. They believe that science improves the well-being of the population, but at the same time increases the danger of the death of mankind. Only by the end of the 20th century, having comprehended both the positive and negative aspects of science, did mankind develop a more balanced position in relation to the role of science in modern society.

Recognizing the important role of science in the life of society, one should not agree with its "claims" for a dominant position. Science in itself cannot be considered the highest value of human civilization, it is only a means in solving some problems of human existence. The same applies to other areas of culture. Only mutually complementing each other, all spheres of culture can fulfill their main function - to provide and facilitate human life. If, in this relationship, some part of culture is given more importance than others, this leads to the impoverishment of culture as a whole and disruption of its normal functioning.

Based on this assessment, science today is considered as a part of culture, which is a set of objective knowledge about being, the process of obtaining this knowledge and applying it in practice.

1.2. Natural science and humanitarian culture

Culture, being the result of human activity, cannot exist in isolation from the natural world, which is its material basis. It is inextricably linked with nature and exists within it, but, having a natural basis, retains its social content. This kind of duality of culture led to the formation of two types of culture: natural science and humanitarian (or two ways of relating to the world, its knowledge). At the initial stage human history both types existed as a whole, since human knowledge was equally directed both at nature and at itself. However, gradually, each type developed its own principles and approaches, defined goals; the natural-scientific culture sought to study nature and conquer it, while the humanitarian one set itself the goal of studying man and his world.

For the first time, the idea of the difference between natural science and humanitarian knowledge was put forward at the end of the 19th century. the German philosopher W. Dilthey and the philosophers of the Baden school of neo-Kantianism W. Windelband and G. Rickert. The terms “science of nature” and “science of the spirit” proposed by them quickly became generally accepted, while the idea itself was firmly established in philosophy. Finally, in 1960-1970. English historian and writer C. Snow formulated the idea of an alternative of two cultures: natural science and humanitarian. He declared that the spiritual world of the intelligentsia is more and more clearly splitting into two camps, in one of which there are artists, in the other - scientists. In his opinion, two cultures are in constant conflict with each other, and mutual understanding between representatives of these cultures is impossible due to their absolute alienation.

A detailed study of the question of the relationship between natural science and humanitarian cultures really allows us to find significant differences between them. Two extreme points vision. Proponents of the first claim that it is natural science, with its precise methods of research, that should become the model that should be imitated by the humanities. Radical representatives of this point of view are positivists, who consider mathematical physics to be the “ideal” of science, and the deductive method of mathematics to be the main method of constructing any scientific knowledge. Proponents of the opposite position argue that such a view does not take into account all the complexity and specifics of humanitarian knowledge and, therefore, is utopian and unproductive.

Focusing on the creative essence of culture, it can be argued that the fundamental feature of natural science culture is its ability to "discover" the world, nature, which are a self-sufficient system that functions according to its own laws, cause-and-effect relationships. Natural science culture focuses on the study and study of natural processes and laws, its specificity lies in high degree objectivity and reliability of knowledge about nature. She strives to read the infinite "book of nature" as accurately as possible, to master its forces, to know it as objective reality that exists independently of the individual.

At the same time, the history of human culture testifies that any spiritual activity of people takes place not only in the form of natural scientific knowledge, but also in the form of philosophy, religion, art, social sciences and the humanities. All these activities constitute the content of humanitarian culture. The main subject of humanitarian culture, therefore, are inner world person, his personal qualities, human relationships, etc., and its specificity is determined by the social position of a person and the spiritual values dominating in society.

The differences between natural science and humanitarian knowledge are caused not only by different goals, subjects and objects of these areas cognitive activity, but also by the two main ways of the thinking process, which are of a physiological nature. It is known that the human brain is functionally asymmetric: its right hemisphere is associated with a figurative intuitive type of thinking, the left - with a logical type. Accordingly, the predominance of one or another type of thinking determines a person's propensity for artistic or rational way perception of the world.

Rational knowledge serves as the basis of natural science culture, since it is focused on the division, comparison, measurement and distribution of knowledge and information about the surrounding world into categories. It is most adapted to the accumulation, formalization and translation of an ever-increasing amount of knowledge. In the aggregate of various facts, events and manifestations of the surrounding world, it reveals something common, stable, necessary and natural, gives them a systemic character through logical comprehension. Natural scientific knowledge is characterized by the desire for truth, the development of a special language for the most accurate and unambiguous expression of the knowledge gained.

Intuitive thinking, on the contrary, is the basis for humanitarian knowledge, since it is individual in nature and cannot be subject to strict classification or formalization. It is based on the inner experiences of a person and does not have strict objective criteria of truth. However, intuitive thinking has great cognitive power, as it is associative and metaphorical in nature. Using the method of analogy, it is able to go beyond logical constructions and give rise to new phenomena of material and spiritual culture.

Thus, the natural science and humanitarian cultures are separated not by chance. But this division does not exclude their initial interdependence, which does not have the character of incompatible opposites, but rather acts as complementarity. The relevance of the problem of interaction between two cultures lies in the fact that they turned out to be too "distant" from each other: one explores nature "in itself", the other - a person "in itself". Each of the cultures considers the interaction of man and nature either in a cognitive or in a “conquering” plan, while an appeal to the being of a person requires deepening the unity not only of natural science and humanitarian cultures, but also the unity of human culture as a whole. The solution to this problem rests on the paradox that the laws of nature are the same for all people and everywhere, but different and sometimes incompatible worldviews, norms and ideals of people.

The fact that there are differences between the natural sciences and the humanities does not negate the need for unity between them, which can only be achieved through their direct interaction. Today, both in the natural sciences and in the humanities, integration processes are intensifying due to common research methods; in this process, the technical equipment of humanitarian research is enriched. Thus, links are established between the humanities and the natural sciences, which are also interested in this. For example, the results of logical and linguistic research are used in the development of natural science information tools. The joint developments of natural scientists and humanities in the field of ethical and legal problems of science are becoming increasingly important.

IN last years under the influence of the achievements of technological progress and such a general scientific method of research as a systematic approach, the previous confrontation between natural scientists and the humanities has significantly weakened. The humanists understood the importance and necessity of using in their knowledge not only the technical and informational means of natural science and the exact sciences, but also effective scientific methods of research that originally arose within the framework of natural science. The experimental method of research from the natural sciences penetrates into the humanities (sociology, psychology); in turn, natural scientists are increasingly turning to the experience of humanitarian knowledge. Thus, we can talk about the humanization of natural science and the scientization of humanitarian knowledge, which are actively taking place today and gradually blurring the boundaries between the two cultures.

1.3. Criteria of scientific knowledge

Throughout its history, mankind has accumulated a huge amount of knowledge about the world, which is different in nature. Along with scientific knowledge, it contains religious, mythological, everyday, etc. The existence of various types of knowledge raises the question of the criteria that make it possible to distinguish scientific knowledge from non-scientific knowledge. In modern science of science, it is customary to single out four main criteria for scientific knowledge.

The first of them is consistency knowledge, according to which science has a certain structure, and is not an incoherent collection of separate parts. The system, unlike the sum, is characterized by internal unity, the impossibility of removing or adding any elements to its structure without good reason. Scientific knowledge always acts as certain systems; these systems have initial principles, fundamental concepts (axioms), as well as knowledge derived from these principles and concepts according to the laws of logic. Based on the accepted initial principles and concepts, new knowledge is substantiated, new facts, results of experiments, observations, and measurements are interpreted. A chaotic set of true statements that are not systematized relative to each other cannot be considered scientific knowledge in itself.

The second criterion of science is the presence of a mechanism for obtaining new knowledge. This provides not only a proven methodology for practical and theoretical research, but also the availability of people who specialize in this activity, relevant organizations, as well as the necessary materials, technologies and means of recording information. Science appears when objective conditions in society, there is a fairly high level of development of civilization.

The third criterion of scientificity is theoretical knowledge, defining goal of scientific knowledge. All scientific knowledge is ordered in theories and concepts that are consistent with each other and with the dominant ideas about the objective world. After all, the ultimate goal of science is to obtain truth for the sake of truth itself, and not for the sake of a practical result. If science is aimed only at solving practical problems, it ceases to be a science in full sense this word. At the heart of science are fundamental research, pure interest in the world around, and then on their basis applied research is carried out, if the state of the art allows it. Thus, the scientific knowledge that existed in the East was used only in religious magical rituals and ceremonies or in direct practical activities. Therefore, we cannot talk about the presence of science there for many centuries as an independent sphere of culture.

The fourth criterion of scientificity is rationality knowledge, i.e., obtaining knowledge only on the basis of rational procedures. Unlike other types of knowledge, scientific knowledge is not limited to stating facts, but seeks to explain them, to make them understandable to the human mind. The rational style of thinking is based on the recognition of the existence of universal causal relationships accessible to the mind, as well as formal proof as the main means of justifying knowledge. Today this position seems trivial, but the knowledge of the world mainly with the help of the mind appeared only in Ancient Greece. Eastern civilization never adopted this specific European path, giving priority to intuition and extrasensory perception.

For science, since the New Age, an additional, fifth criterion of scientificity has been introduced. It's presence experimental method of research, mathematization of science, which connected science with practice, created a modern civilization focused on the conscious transformation of the surrounding world in the interests of man.

Using the above criteria, one can always distinguish scientific knowledge from non-scientific knowledge (pseudo-sciences). This is especially important today, because in Lately pseudoscience, which has always existed side by side with science, attracts everything more supporters.

The structure of pseudoscientific knowledge is usually not systemic, but rather fragmentary. Pseudoscience is characterized by an uncritical analysis of initial data (myths, legends, stories of third parties), disregard for contradictory facts, and often even a direct juggling of facts.

Despite this, pseudoscience is a success. There are appropriate reasons for this. One of them is the fundamental incompleteness of the scientific worldview, leaving room for conjectures and fabrications. But if earlier these voids were mainly filled with religion, today pseudoscience has taken their place, whose arguments, if incorrect, are clear to everyone. Pseudo-scientific explanations are more accessible to an ordinary person than dry scientific reasoning, which is often impossible to understand without special education. Therefore, the roots of pseudoscience lie in the very nature of man.

The first are relic pseudoscience, among which are well-known astrology and alchemy. Once upon a time they were a source of knowledge about the world, a breeding ground for the birth of genuine science. They became pseudosciences after the advent of chemistry and astronomy.

In modern times appeared occult pseudosciences - spiritualism, mesmerism, parapsychology. Common to them is the recognition of the existence of the other world (astral) world, not subject to physical laws. It is believed that this is the highest world in relation to us, in which any miracles are possible. You can contact this world through mediums, psychics, telepaths, and various paranormal activity which become the subject of pseudoscience.

In the 20th century there were modernist pseudoscience, in which the mystical basis of the old pseudosciences has been transformed by science fiction. Among such sciences, the leading place belongs to ufology, which studies UFOs.

How to separate genuine science from fakes for it? To do this, the methodologists of science, in addition to the criteria of scientificity already mentioned by us, have formulated several important principles.

The first one is verification principle(practical verifiability): if a concept or judgment is reducible to direct experience (i.e., empirically verifiable), then it makes sense. In other words, scientific knowledge can be tested against experience, while non-scientific knowledge cannot be tested.

A distinction is made between direct verification, when there is a direct verification of statements, and indirect, when logical relationships are established between indirectly verified statements. Since the concepts of a developed scientific theory, as a rule, are difficult to reduce to experimental data, indirect verification is used for them, which states: if it is impossible to experimentally confirm some concept or proposition of the theory, one can confine oneself to experimental confirmation of the conclusions from them. For example, the concept of "quark" was introduced in physics as early as the 1930s, but such a particle of matter could not be detected in experiments. At the same time, quark theory predicted a number of phenomena that allowed experimental verification, in the course of which the expected results were obtained. This indirectly confirmed the existence of quarks.

Immediately after its appearance, the principle of verification was sharply criticized by its opponents. The essence of the objections boiled down to the fact that science cannot develop only on the basis of experience, since it presupposes obtaining results that are not reducible to experience and cannot be directly derived from it. In science, there are formulations of laws that cannot be verified by the criterion of verification. In addition, the very principle of verifiability is “unverifiable”, i.e., it should be classified as meaningless, subject to exclusion from the system of scientific statements.

In response to this criticism, scientists have proposed another criterion for distinguishing between scientific and non-scientific knowledge - falsification principle, formulated by the largest philosopher and methodologist of science of the XX century. K. Popper. In accordance with this principle, only fundamentally refutable (falsifiable) knowledge can be considered scientific. It has long been known that no amount of experimental evidence is sufficient to prove a theory. So, we can observe as many examples as we like, every minute confirming the law gravity. But one example is enough (for example, a stone that did not fall to the ground, but flew away from the ground) to recognize this law as false. Therefore, a scientist should direct all his efforts not to search for another experimental proof of the hypothesis or theory formulated by him, but to an attempt to refute his statement; the critical striving to refute a scientific theory is the most effective way of confirming its scientificity and truth. Critical refutation of the conclusions and statements of science does not allow it to stagnate, is the most important source of its growth, although it makes any scientific knowledge hypothetical, depriving it of completeness and absoluteness.

The falsification criterion has also been criticized. It has been argued that the principle of falsifiability is insufficient, since it is inapplicable to those provisions of science that cannot be compared with experience. In addition, real scientific practice contradicts the immediate rejection of a theory if the only empirical fact that contradicts it is discovered.

In fact, true science is not afraid to make mistakes, to recognize its previous conclusions as false. If, however, some concept, for all its scientism, claims that it cannot be refuted, denies the very possibility of a different interpretation of any facts, this indicates that we are faced not with science, but with pseudoscience.

1.4. Structure of scientific knowledge

The term "science" is usually understood as a special field of human activity, the main purpose of which is the development and theoretical systematization of objective knowledge about all aspects and areas of reality. With this understanding of the essence of science, it is a system, the diverse elements of which are interconnected by common philosophical and methodological foundations. The elements of the system of science are various natural, social, humanitarian and technical scientific disciplines (individual sciences). Modern science includes more than 15,000 different disciplines, and the number of professional scientists in the world has exceeded 5 million people. Therefore, science today has a complex structure, which can be considered in several aspects.

In modern science of science, the main basis for classification scientific disciplines is the subject of research. Depending on the sphere of being, which acts as the subject of research of science, it is customary to distinguish between natural (a complex of sciences about nature), social (sciences about types and forms public life) and the humanities (studying man as a thinking being) sciences. This classification is based on the division of the world around us into three areas: nature, society and man. Each of these areas is studied by a corresponding group of sciences, and each group, in turn, is a complex set of many independent sciences interacting with each other.

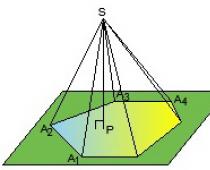

So, natural science, the subject of which is nature as a whole, includes physics, chemistry, biology, earth sciences, astronomy, cosmology, etc. Social science is economic sciences, law, sociology, political sciences. The complex of the humanities is formed by psychology, logic, cultural studies, linguistics, art history, etc. A special place is occupied by mathematics, which, contrary to a widespread misconception, is not part of natural science. It is an interdisciplinary science that is used by both natural and social sciences and the humanities. Mathematics is often referred to as the universal language of science; the special place of mathematics is determined by the subject of its research. This is the science of the quantitative relations of reality (all other sciences have as their subject some qualitative side of reality), it is more general, abstract than all other sciences, it “doesn’t care” what to count (see Table 1.1).

According to the orientation towards the practical application of the results, all sciences are combined into two large groups: fundamental and applied. Fundamental sciences - a system of knowledge about the deepest properties of objective reality that does not have a pronounced practical orientation. Such sciences create theories that explain the foundations of human existence; the fundamental knowledge of these theories determines the features of a person’s idea of the world and himself, i.e., they are the basis for scientific picture peace. As a rule, fundamental research is carried out not because of external (social) needs, but because of internal (immanent) incentives; fundamental sciences are characterized by axiological (value) neutrality. The discoveries and achievements of the fundamental sciences are decisive in the formation of the natural-scientific picture of the world, in changing the paradigm of scientific thinking. In the fundamental sciences, basic models of cognition are developed, concepts, principles and laws that form the basis of applied sciences are revealed. The fundamental sciences include mathematics, natural sciences (astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, anthropology), Social sciencies(history, economics, sociology, philosophy), humanities (philology, psychology, cultural studies).

Applied Science, on the contrary, they are considered as a system of knowledge with a clearly defined practical orientation. Based on the results of fundamental research, they are guided by the solution of specific problems related to the interests of people. Applied sciences are ambivalent, that is, depending on the scope of application, they can have both a positive and a negative impact on a person, they are value-oriented. Applied sciences include technical disciplines, agronomy, medicine, pedagogy, etc.

There is a dichotomy (contradiction) between fundamental and applied sciences, which has historical roots. In the course of fundamental research, applied problems can be set and solved, and applied research often requires extensive use of fundamental developments, especially in interdisciplinary areas. However, this dichotomy is not of a fundamental nature, as can be seen from an analysis of the relationship between the natural and technical sciences. It is the development of technical sciences that clearly demonstrates the conventionality of the boundaries between fundamental and applied research.

1.5. Scientific picture of the world

In the process of cognition of the surrounding world, the results of cognition are reflected and fixed in the human mind in the form of knowledge, skills, behaviors and communication. The totality of the results of human cognitive activity forms a certain model, a picture of the world. In the history of mankind, a fairly large number of the most diverse pictures of the world were created and existed, each of which was distinguished by its vision of the world and its explanation. However, the broadest and most complete picture of the world is given by the scientific picture of the world, which includes major achievements sciences that create a certain understanding of the world and man's place in it. The scientific picture of the world does not include private knowledge about the various properties of specific phenomena, about the details of the cognitive process itself; it is an integral system of ideas about the general properties, spheres, levels and patterns of reality. At its core, the scientific picture of the world is a special form of systematization of knowledge, a qualitative generalization and ideological synthesis of various scientific theories.

Being an integral system of ideas about the general properties and regularities of the objective world, the scientific picture of the world exists as a complex structure that includes the general scientific picture of the world and the picture of the world of a separate science (physical, biological, geological, etc.) as components. The picture of the world of a separate science, in turn, includes the corresponding numerous concepts - certain ways of understanding and interpreting any objects, phenomena and processes of the objective world.

The basis of the modern scientific picture of the world is the fundamental knowledge obtained primarily in the field of physics. However, in the last decades of the twentieth century the opinion is increasingly asserted that biology occupies a leading position in the modern scientific picture of the world. This is expressed in the strengthening of the influence that biological knowledge has on the content of the scientific picture of the world. The ideas of biology gradually acquire a universal character and become the fundamental principles of other sciences. In particular, this is the idea of development, the penetration of which into cosmology, physics, chemistry, anthropology, sociology, etc., has led to a significant change in man's views on the world.

The concept of a scientific picture of the world is one of the fundamental ones in natural science. Throughout its history, it has gone through several stages of development and, accordingly, the formation of scientific pictures of the world as a separate science or branch of science dominates, based on a new theoretical, methodological and axiological system of views adopted as the basis for the decision. scientific tasks. Similar system scientific views and attitudes, shared by the overwhelming majority of scientists, is called a scientific paradigm.

In relation to science, the term "paradigm" in the general sense means a set of ideas, theories, methods, concepts and models for solving various scientific problems. At the level of the paradigm, the basic norms for distinguishing between scientific and non-scientific knowledge are formed. As a result of the paradigm shift, there is a change in the standards of scientificity. Theories formulated in different paradigms cannot be compared because they rely on different standards of scientificity and rationality.

In the science of science, it is customary to consider paradigms in two aspects: epistemic (epistemological) and social. Epistemically, a paradigm is a collection of fundamental knowledge, values, beliefs, and techniques serving as a sample scientific activity. IN social relations the paradigm determines the integrity and boundaries of the scientific community that shares its main provisions.

During the period of domination of any paradigm in science, a relatively calm development of science takes place, but over time it is replaced by the formation of a new paradigm, which is affirmed through a scientific revolution, i.e., a transition to a new system of scientific values and worldview. The philosophical concept of a paradigm is productive in describing the basic theoretical and methodological foundations of the scientific study of the world and is often used in the practice of modern science.

Table 1.1. Duration of some physical processes (sec)

A.P. Sadokhin

Concepts of modern natural science

Tutorial

Introduction

Modern science unites more than a thousand different scientific disciplines, each of which contains special theories, concepts, methods of cognition and methods of conducting experiments. Achievements of science lay the foundations of a person's worldview. In this process, one of the main places belongs to natural scientific knowledge, which is formed by a whole group of natural sciences that create a holistic and adequate idea of the objective world.

At the same time, the modern level of development of society imposes increased requirements on the level vocational training specialists, in which a significant place belongs to natural science knowledge. Today, society needs specialists who are focused not only on solving utilitarian problems within the limits of knowledge gained during training. Modern requirements to a specialist are based on his ability to constantly improve his skills, the desire to keep abreast of the latest achievements in the profession, the ability to creatively adapt them to his work. The education system is faced with the task of training highly qualified specialists with fundamental, versatile knowledge about various processes and phenomena of the surrounding world. To this end, in educational plans higher educational institutions such disciplines and lecture courses are included, which should form the student's broad worldview orientations and attitudes, help him to better master the scientific picture of the world and his chosen profession. The course "Concepts of modern natural science" is called upon to realize these goals.

This discipline does not involve a deep and detailed study of all natural laws and processes, phenomena and facts, methods and experiments. The purpose of the course is to familiarize with the main provisions and the current state of development of the natural sciences, helping to form an idea of the complete picture of the world around us, the place of a person in it, and to understand the problems of the development of society.

The key word of the course is the concept of "concept" (from lat. conception- understanding, explanation), which means a relatively systematic explanation or understanding of some phenomena or events. For this training course it presupposes a popular meaningful description of natural scientific knowledge that forms a general picture of the world in the human mind. Various natural-scientific ideas about the structure of the world represent the basic knowledge necessary to understand the world in accordance with the level of knowledge of each era. In addition, without natural science knowledge it is difficult to understand not only the development of technology and technology, but also the development of society and culture.

The course "Concepts of modern natural science" covers the main problems, ideas and theories of natural sciences, scientific principles of cognition, methodology, models and results of modern natural science, which together constitute the scientific picture of the world. In this regard, the objective of the course is to form knowledge about interdisciplinary, general scientific approaches and methods, develop systemic thinking in the course of analyzing the problems of modern natural science, and expand the cognitive horizons of students by going beyond the boundaries of their narrow professional interests.

As a result of studying the discipline, students should gain knowledge that allows them to take into account the fundamental laws of nature and the main methods of research, as well as information about the most important historical stages and ways of developing natural science in their future professional activities.

The training manual has been prepared in accordance with the State educational standard higher vocational education, which is introduced into the curricula for students of all humanitarian specialties. It is based on textbooks previously published by the author and courses of lectures given by the author in various universities.

The experience of teaching this discipline to students of various humanitarian specialties shows that one should not present the material of the natural sciences, delving into “technical details”, if this is not justified by the general idea and methodological approach to the presentation of the subject. The author saw his main task in making the form of presentation of the material accessible for assimilation by future specialists, for whom natural science is not a professional discipline.

The range of humanitarian specialties in the system higher education is quite wide and varied, so the author tried to give his work a universal character so that it would be useful for students of various humanitarian specialties - economists, psychologists, philosophers, historians, sociologists, managers, lawyers, etc. Such an orientation of the textbook implies a conscious refusal to master physical And chemical formulas, remembering numerous rules and laws and focusing on the most important concepts of modern natural science, which are the foundation of the scientific picture of the world. The textbook is both a scientific and popular publication, providing a quick and accessible introduction to the problems of the natural sciences for a wide range of readers.

The author expresses his gratitude to the reviewers and fellow teachers for their valuable comments and recommendations made during the creation of the textbook, as well as to all interested readers for their possible comments and suggestions.

Chapter 1. Science in the context of culture

1.1. Science as part of culture

Throughout their history, people have developed many ways of knowing and mastering the world around them. Among them, one of the most important places is occupied by science, the main purpose of which is the description, explanation and prediction of the processes of reality that constitute the subject of its study. In the modern sense, science is seen as:

The highest form of human knowledge;

Social institution, consisting of various organizations and institutions engaged in obtaining new knowledge about the world;

System of developing knowledge;

Way of knowing the world;

A system of principles, categories, laws, techniques and methods for obtaining adequate knowledge;

Element of spiritual culture;

The system of spiritual activity and production.

All the given meanings of the term "science" are legitimate. But this ambiguity also means that science is a complex system designed to provide generalized holistic knowledge about the world. At the same time, this knowledge cannot be disclosed by any one separate science or a set of sciences.

To understand the specifics of science, it should be considered as part of a culture created by man, compared with other areas of culture.

A specific feature of human life is the fact that it proceeds simultaneously in two interrelated aspects - natural and cultural. Initially, a person is a living being, a product of nature, however, in order to exist comfortably and safely in it, he creates an artificial world of culture inside nature, a “second nature”. Thus, a person exists in nature, interacts with it like a living organism, but at the same time “doubles” the outside world, developing knowledge about it, creating images, models, assessments, household items, etc. It is this kind of material-cognitive activity of a person and constitutes the cultural aspect of human existence.

Culture finds its embodiment in the objective results of activity, ways and methods of human existence, in various norms of behavior and various knowledge about the world around. The whole set of practical manifestations of culture is divided into two main groups: material and spiritual values. Material values form material culture, and the world of spiritual values, which includes science, art, religion, forms the world of spiritual culture.

Spiritual culture covers the spiritual life of society, its social experience and results, which appear in the form of ideas, scientific theories, artistic images, moral and legal norms, political and religious views and other elements of the human spiritual world.

An integral part of culture is science, which determines many important aspects of the life of society and man. It, like other spheres of culture, has its own tasks that distinguish them from each other. Thus, the economy is the foundation that ensures all the activities of society; it arises on the basis of a person's ability to work. Morality regulates relations between people in society, which is very important for a person who cannot live outside society and must limit his own freedom in the name of the survival of the entire team. Religion arises from a person's need for consolation in situations that cannot be resolved rationally (for example, the death of loved ones, illness, unhappy love, etc.).

n1.doc

A.P. SADOKHINCONCEPTS

MODERN

NATURAL SCIENCE

Second edition, revised and enlarged

Russian Federation as textbook

For university students,

students in the humanities

"Professional textbook" as textbook

for university students studying

in the specialties of economics and management

and humanitarian and social specialties

UDC 50(075.8)

Reviewers:

Dr. Philosophy Sciences, Prof., Academician of the Russian Academy of Natural Sciences A.V. Soldiers;

Cand. biol. Sciences, Associate Professor L.B. Angler;

Cand. chem. Sciences, Associate Professor N.N. Ivanova

Editor-in-chief of the publishing house

PhD in Law,

Doctor of Economic Sciences N.D. Eriashvili

Sadokhin, Alexander Petrovich.

C14 Concepts of modern natural science: a textbook for university students studying in the humanities and specialties of economics and management / A.P. Sadokhin. - 2nd ed., revised. and additional - M.: UNITI-DANA, 2006. - 447 p.

ISBN 5-238-00974-7

Agency CIP RSL

The textbook has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the State Educational Standard for Higher Professional Education in the discipline "Concepts of Modern Natural Science", which is included in the curricula of all humanitarian specialties of universities. The paper presents a wide panorama of concepts that illuminate various processes and phenomena in animate and inanimate nature, describes modern scientific methods of understanding the world. The main attention is paid to the consideration of the concepts of modern natural science, which have an important philosophical and methodological significance.

For students, graduate students and teachers of humanitarian faculties and universities, as well as all those interested in the philosophical issues of natural science.

ISBN 5-238-00974-7

© A.P. Sadokhin, 2006

© UNITY-DANA PUBLISHING HOUSE, 2003, 2006 Reproduction of the entire book or any part of it by any means or in any form, including on the Internet, is prohibited without the written permission of the publisher

The proposed textbook has been prepared in accordance with the State Educational Standard of Higher Professional Education and is intended for students of humanitarian specialties at universities.

It is well known that modern system education should solve the problem of training highly qualified specialists with versatile and fundamental knowledge about a wide variety of processes and phenomena of the surrounding world. Today, society does not need specialists focused only on solving narrow utilitarian tasks. A highly qualified professional in demand on the labor market must have a broad outlook, the skills of independently acquiring new knowledge and their critical reflection. In addition, he must have an idea of the basic scientific concepts that explain the spatio-temporal relations of the objective world, the processes of self-organization in complex systems, such as animate and inanimate nature, the relationship of man with the environment. natural environment and man's place in the universe.

To this end, the curriculum of all higher educational institutions includes the discipline "Concepts of modern natural science", designed to form students' broad worldview orientations and attitudes, to help them master the scientific picture of the world.

The purpose of the course "Concepts of modern natural science" is to familiarize students of humanitarian specialties of universities with an integral component of human culture - natural science. At the same time, the main attention is paid to the consideration of those concepts of modern natural science that have the most important philosophical and methodological significance for understanding and analyzing social phenomena.

The training course "Concepts of modern natural science" in its content is an interdisciplinary complex based on the historical-philosophical, cultural and evolutionary-synergetic approaches to modern natural science. The current trend towards a harmonious synthesis of humanitarian and natural science knowledge is due to the needs of society in a holistic worldview and emphasizes the relevance of this discipline.

The need to study this course is also due to the fact that over the past two decades in our society, various types of

The types of irrational knowledge are mysticism, astrology, occultism, magic, spiritualism, etc. Gradually and consistently they try to force out public consciousness a scientific picture of the world based on rational ways of explaining it. Under these conditions, the following are of particular importance: the assertion of a scientific and rational attitude to reality, a holistic view of animate and inanimate nature, an understanding of the content and capabilities of modern methods of scientific knowledge, as well as the ability to apply them in professional activities.

The experience of teaching this discipline in humanitarian universities shows that when presenting the material of the natural sciences, if possible, excessive detail should be avoided, if this is not justified by the general idea and methodological approach to the presentation of this subject. It is advisable to focus on those most important concepts of modern natural science, which form the foundation of the modern scientific picture of the world and are most important in the worldview aspect. Thus, the author saw his main task in making the form of presentation of the material as accessible as possible for assimilation by those future specialists for whom natural science is not the main professional discipline. However, since the range of humanitarian specialties is quite wide and varied, the author sought to give his work a universal character, so that it would thus be equally useful for students of all humanitarian specialties - future economists, psychologists, historians, sociologists, managers, etc.

Offering his work to a wide audience, the author expresses his gratitude to the reviewers and fellow teachers for valuable comments and recommendations, which provided invaluable assistance in the creation of this textbook. In addition, the author expresses his sincere gratitude in advance to all interested readers for their well-meaning wishes and comments.

Chapter 1

Science as part of culture

1.1. Science among other spheres of culture

Throughout the history of its existence, people have developed many ways of knowing and mastering the world around them. Among them, one of the most important places is occupied by science. To understand its specificity, it is necessary to consider science as part of a culture created by man, and also to compare it with other areas of culture.

A specific feature of human life is the fact that it proceeds simultaneously in two interrelated aspects: natural and cultural. Initially, a person is a living being, a product of nature, but in order to exist comfortably and safely in it, a person creates an artificial world of culture inside nature, a “second nature”. Thus, a person exists in nature, interacts with it like a living organism, but at the same time, he, as it were, doubles the outside world, developing knowledge about it, creating images, models, assessments, household items, etc. It is this material-cognitive activity of man that constitutes the cultural aspect of human existence.

Culture finds its embodiment in the objective results of activity, ways and methods of human existence, in various norms of behavior and various knowledge about the world around. The whole set of practical manifestations of culture is divided into two main groups: material and spiritual values. Material values form material culture, and the world of spiritual values, which includes science, art, religion, forms the world of spiritual culture.

Spiritual culture covers the spiritual life of society, its social experience and results, which appear before us in the form of ideas, ideas, scientific theories, artistic images, moral and legal norms, political and religious views and many other elements of the human spiritual world.

Culture is the most important essential characteristic of a person, which distinguishes him from the rest of the organic world of our planet. With its help, a person does not adapt to

The environment, such as plants and animals, but rather changes it, transforms the world, making it comfortable for itself. This manifests the most important function of culture - protective, aimed at directly or indirectly facilitating people's lives. All spheres of culture in one way or another participate in solving this most important task, while reflecting certain personal characteristics of a person, as well as his needs and interests.

In this context, an integral part of culture is science, which determines many important aspects of the life of society and man. Science has its own tasks that distinguish it from other spheres of culture. Thus, the economy is the foundation that ensures all the activities of society; it arises on the basis of a person's ability to work. Morality regulates relations between people in society, which is very important for a person who cannot live outside society and must limit his own freedom in the name of the survival of the entire team, creating moral standards. Religion is born out of a person's need for consolation in those situations that cannot be resolved rationally (for example, the death of loved ones, illness, unhappy love, etc.).

The task of science is to obtain objective knowledge about the surrounding world, the knowledge of the laws by which it functions and develops. With this knowledge, it is much easier for a person to transform the world. Thus, science is a sphere of culture most closely associated with the task of directly transforming the world, increasing its comfort and convenience for humans. It was the rapid growth of science, which began in modern times, that created the modern technical civilization - the world in which we live today.

It is not surprising that the many positive aspects of science formed its high authority, led to the emergence of scenetizma- a worldview based on faith in science as the only saving force designed to solve all human problems. Ideology antiscientism, which considers science a harmful and dangerous force leading to the death of mankind, could not compete with it until recently, although it referred to the negative consequences of scientific and technological progress, including the creation of weapons of mass destruction and the ecological crisis.

Only by the end of the 20th century, having comprehended both the positive and negative aspects of science, did mankind develop a more balanced position. While recognizing the important role of science in our life, one should not agree with its claims to a dominant place in the life of society. Science in itself cannot be considered the highest value of human civilization, it is only a means in solving some problems of human existence.

Nia. The same applies to other areas of culture. Only mutually complementing each other, all spheres of culture can fulfill their main function - to provide for the needs and make life easier for a person, being a link between a person and nature. If in this relationship any one part is given more importance than others, then this leads to the impoverishment of culture as a whole and disruption of its normal functioning.

In this way, the science- this is a part of culture, which is a set of objective knowledge about being, the process of obtaining this knowledge and applying it in practice.

1.2. Natural science and humanitarian culture

Culture, being the result of human activity, cannot exist in isolation from the natural world, which is its material basis. It is inextricably linked with nature and exists within it, but, having a natural basis, culture at the same time retains its social content. This kind of duality led to the formation of two types of culture: natural science and humanitarian. It would be more correct to call them two ways of relating to the world, as well as to its knowledge.

At the initial stage of human history, natural-beginning and humanitarian cultures existed as a whole, since human knowledge was equally directed both at the study of nature and at the knowledge of oneself. However, gradually they developed their own principles and approaches, defined goals: the natural science culture sought to study nature and conquer it, and the humanitarian culture set as its goal the study of man and his world.

The separation of natural science and humanitarian cultures began in antiquity, when astronomy, mathematics, geography, on the one hand, and theater, painting, music, architecture and sculpture, on the other hand, appeared. In the Renaissance, art became an important part of society, and therefore the humanitarian culture developed especially intensively. Modern times, on the contrary, are characterized by exceptionally rapid development of natural science. This was facilitated by the emerging capitalist mode of production and new production relations. The successes of the natural sciences at that time were so impressive that the idea of their omnipotence arose in society. Need

Increasingly deeper knowledge of the surrounding world and the outstanding successes of natural science in this process led to the differentiation of the natural sciences themselves, i.e. to the emergence of physics, chemistry, geology, biology and cosmology.

For the first time, the idea of the difference between natural science and humanitarian knowledge was put forward at the end of the 19th century. the German philosopher W. Dilthey and the philosophers of the Baden school of neo-Kantianism W. Windelband and G. Rickert. The terms “sciences of nature” and “sciences of the spirit” proposed by them quickly became generally accepted, and the idea itself was firmly established in philosophy. Finally, in the 60s and 70s. 20th century English historian and writer C. Snow formulated the idea of alternative two cultures: natural science and humanitarian. He stated that the spiritual world of the intelligentsia is more and more clearly splitting into two camps, in one of them - the artistic intelligentsia, in the other - scientists. In his opinion, it can be concluded that there are two cultures that are in constant conflict with each other, and mutual understanding between representatives of these cultures is impossible due to their absolute alienation.

A thorough and in-depth study of the relationship between natural science and humanitarian cultures allows us to conclude that there really are considerable differences between them. There are two extreme points of view here. Proponents of the first of these claim that it is natural science, with its precise methods of research, that is the model that the humanities should imitate. The most radical representatives of this point of view are the positivists, who consider mathematical physics to be the ideal of science, and the deductive method of mathematics to be the main method of constructing any scientific knowledge. Defenders of the opposite position rightly argue that such a view does not take into account all the complexity and specifics of humanitarian knowledge and, therefore, is utopian and unproductive.

Focusing on the active, creative essence of culture, it can be argued that the fundamental feature of natural science culture is that it "discovers" the natural world, nature, which is a self-sufficient system that functions in accordance with its own laws. This is precisely why natural science culture focuses on the study and study of natural processes and the laws that govern them. She strives to read the infinite "book of nature" as accurately as possible, to master its forces, to know it as an objective reality that exists independently of man.

At the same time, the history of human culture also shows that any spiritual activity of people takes place not only in the form of natural scientific knowledge, but also in the form of philosophy, religion, art, social sciences and the humanities. All these activities constitute the content of humanitarian culture. Thus, the main subject of humanitarian culture is the inner world of a person, his personal qualities, human relationships, etc. In other words, its most important feature is that the main problem for a person is his own being, the meaning, norms and purpose of this being.

All of the above gives reason to assert that there are considerable differences between natural science and the humanities. These differences are due not only to different goals, subjects and objects of these areas of cognitive activity, but also to two main ways of the thinking process that have a physiological nature. Today it is reliably known that the human brain is functionally asymmetric: its right hemisphere is associated with a figurative intuitive type of thinking, and the left - with a logical one. The predominance of one or another type of thinking determines a person's inclination to a rational or artistic type of perception of the world.

Rational knowledge serves as the basis of natural science culture, since it is focused on the division, comparison, measurement and distribution of knowledge and information about the surrounding world into categories. It is most adapted to the formalization, accumulation and transmission of an ever-increasing amount of knowledge. In the aggregate of various facts, events and manifestations of the surrounding world, it reveals the general, stable, necessary and natural, gives them a systemic character through logical comprehension. Due to the above features, natural scientific knowledge is characterized by the desire for truth, the development of a special language for the most accurate and unambiguous expression of the knowledge gained.

Intuitive thinking, on the contrary, is the basis for humanitarian knowledge, since it has an individual character and therefore cannot be subject to strict classification or formalization. It is based on the inner experiences of a person and does not have strict objective criteria of truth. However, it has great cognitive power, as it is associative and metaphorical in nature. Using the method of analogy, it is able to go beyond logical constructions and give rise to new phenomena of material and spiritual culture.

Thus, the natural science and humanitarian cultures are not isolated by chance, their differences are great. However, this

The separation does not exclude their initial interdependence, which does not have the character of incompatible opposites, but rather acts as complementarity. The acuteness and relevance of the problem of interaction between two cultures lies in the fact that they turned out to be too distant from each other. One of them explores nature "in itself", and the other - a person and society "in itself". At the same time, each of the cultures considers the interaction of man and nature either only in a cognitive or only in a “conquering” plan, while an appeal to the being of a person requires deepening the unity not only of natural science and humanitarian cultures, but also the unity of all human culture in in general. However, the solution to this problem rests on a paradox, which consists in the fact that the laws of nature are the same for all people and everywhere, but different and hostilely incompatible worldviews, norms and ideals of attitude towards oneself, towards other people and the world around.

The statement of the fact of the existence of certain differences between the natural-science and humanitarian cultures does not negate the possibility of unity between them, which can be achieved only through their direct interaction. Today it is obvious that both in the natural sciences and in the humanities, integration processes are intensifying due to direct links between the natural and human sciences and due to general research methods. In this process, the technical equipment of humanitarian research is enriched. Thus, connections are established between the humanities and the natural sciences, which are also interested in this. For example, the results of logical and linguistic research are used in the development of natural science information tools. The joint developments of natural scientists and humanities in the field of ethical and legal problems of science are also becoming increasingly important.

In recent years, under the influence of the achievements of scientific and technological progress and such a new general scientific method of research as a systematic approach, the previous confrontation between natural scientists and the humanities has significantly weakened. The humanists understood the importance and necessity of using in their knowledge not only the technical and informational means of natural science and the exact sciences, but also effective scientific methods of research that originally arose within the framework of natural science. For example, the experimental method of research from the natural sciences penetrates into the humanities (sociology, psychology). In turn, natural scientists are increasingly turning to the experience of humanitarian knowledge. Thus, we can talk about the humanization of natural science and the scientization of humanitarian knowledge, which are actively taking place today and blurring the boundaries between the two cultures.

1.3. Criteria of scientific knowledge

Throughout its history, mankind has accumulated a huge amount of knowledge about the world, which is different in nature. Along with scientific knowledge, there are religious, mythological, everyday knowledge, etc. The existence of different types of knowledge raises the question of the criteria for distinguishing scientific knowledge from non-scientific.

We single out four criteria of scientific knowledge: 1) systematic knowledge; 2) the presence of a proven mechanism for obtaining new knowledge; 3) theoretical knowledge; 4) rationality of knowledge.

Consistency of knowledge

The first of the scientific criteria is consistency knowledge. The system, unlike the sum of certain elements, is characterized by internal unity, the impossibility of removing or adding any elements to its structure without good reason. Scientific knowledge always acts as certain systems: in these systems there are initial principles, fundamental concepts (axioms), as well as knowledge derived from these principles and concepts according to the laws of logic. In addition, the system includes interpreted experimental facts, experiments, which are important for the given science. mathematical apparatus, practical conclusions and recommendations. A chaotic set of true statements cannot be considered science in itself.

The presence of a proven mechanism for obtaining new knowledge

The second criterion of science is the presence of waste furnism to gain new knowledge. In other words, science is not just a system of knowledge, but also an activity to obtain it, which provides not only a proven methodology for practical and theoretical research, but also the presence of people specializing in this activity, relevant organizations coordinating research, as well as the necessary materials, technologies and means of fixing information. This means that science appears only when objective conditions are created for this in society, i.e. there is a fairly high level of development of civilization.

Theoretical knowledge

The third criterion of scientificity is theoretical knowledge, defining the goals of scientific knowledge. Theoretical knowledge

It involves obtaining truth for the sake of truth itself, and not for the sake of a practical result. If science is aimed only at solving practical problems, it ceases to be science in the full sense of the word. Science is based on fundamental research, a pure interest in the surrounding world, and then applied research is carried out on their basis, if they are allowed by the existing level of technological development. Yes, on Ancient East scientific knowledge was used only in religious magical rituals and ceremonies or in direct practical activities, therefore, in this case, we cannot speak of the existence of science as an independent sphere of culture.

The rationality of knowledge. Availability of an experimental research method

The fourth criterion of scientificity is rationality of knowledge. The rational style of thinking is based on the recognition of the existence of universal causal relationships accessible to the mind, as well as formal proof as the main means of justifying knowledge. Today this provision seems trivial, but the knowledge of the world mainly with the help of the mind appeared only in Ancient Greece. Eastern civilization never adopted this specifically European path, giving priority to intuition and extrasensory perception.

For science, starting from the New Age, an additional, fifth criterion of scientificity is introduced - this is the presence of an experimentalresearch method, as well as the mathematization of science. This criterion linked modern science with practice, created a modern civilization focused on the conscious transformation of the surrounding world in the interests of man.

How to distinguish genuine science from pseudoscience

Using the introduced criteria, one can always distinguish scientific knowledge from non-scientific. This is especially important today, since in recent times pseudoscience, which has always existed alongside science, is becoming increasingly popular and attracting an increasing number of supporters and adherents.

to scientific knowledge. The mass consciousness, which does not see the difference between science and pseudoscience, often sympathizes with pseudoscientists, who, unlike real scientists, tend to be in the public eye. Therefore, one should clearly understand what pseudoscience is, know how it differs from genuine science.

The most important difference between science and pseudoscience is containingknowledge: statements of pseudoscience usually do not agree with the established facts, do not withstand objective experimental verification. So, many times scientists have already tried to check the accuracy of astrological forecasts by comparing the occupation of people and their personality type with horoscopes compiled for them, which take into account the sign of the Zodiac, the location of the planets at the time of birth, and so on, but no significant correspondences were found.

The structure of pseudoscientific knowledge is usually not systemic, but differs fragmentation. As a result, they usually cannot fit logically into any detailed picture of the world.

It is also characteristic of pseudoscience non-critical analysis of source data, which allows us to accept as such myths, legends, third-hand stories, neglect of contradictory facts, ignoring those data that contradict the concept being proved. Often it comes to direct forgery, juggling of facts.

Despite this, pseudoscience is a great success. And there are reasons for this. One of them is the fundamental incompleteness of the scientific worldview, leaving room for conjectures and fabrications. But if earlier these voids were mainly filled with religion, today they are occupied by pseudoscience, whose arguments, perhaps, are incorrect, but are understandable to everyone. Psychologically, an ordinary person is more understandable and more pleasant pseudo-scientific explanations that leave room for miracles that a person needs than dry scientific reasoning, which, moreover, is often impossible to understand without special education. Therefore, the roots of pseudoscience lie in the very nature of man.

In terms of its content, pseudoscience is not homogeneous; several categories of pseudosciences can be distinguished in it.

The first category is relic pseudo-sciences, among which are well-known astrology and alchemy. Once upon a time they were a source of knowledge about the world, a breeding ground for the birth of genuine science. They became pseudosciences after the advent of chemistry and astronomy.

In modern times, occult pseudosciences appeared - spiritualism, mesmerism, parapsychology. Common to them is the recognition of the existence of the other world (astral) world, not subject to physical laws. It is believed that this is the highest world in relation to us, in which any miracles are possible. Holy

You can call with this world through mediums, psychics, telepaths, and various paranormal phenomena arise, which become the subject of study of pseudoscience.

In the XX century. modernist pseudosciences emerged, in which the mystical basis of the old pseudosciences was transformed under the influence of science fiction. Among such sciences, the leading place belongs to ufology, which studies UFOs.

How to distinguish genuine science from fakes for it? To this end, the methodologists of science, in addition to the criteria of scientificity already mentioned by us, have formulated several important principles.

The first one is verification principle, asserting that if any concept or judgment is reducible to direct experience, i.e. empirically verifiable, then it makes sense. A distinction is made between direct verification, when there is a direct verification of statements, and indirect verification, when logical relationships are established between indirectly verified statements. Since the concepts of a developed scientific theory, as a rule, are difficult to reduce to experimental data, indirect verification is used for them, which states that if it is impossible to experimentally confirm some concept or proposition of the theory, then one can restrict oneself to experimental confirmation of their conclusions. So, although the concept of "quark" was introduced in physics back in the 30s. XX century, however, it was not possible to detect such a particle in experiments. At the same time, quark theory predicted a number of phenomena that allowed experimental verification. In the course of it, the expected results were obtained. This indirectly confirmed the existence of quarks.

However, the principle of verification only in the first approximation separates scientific knowledge from non-scientific. Works more accurately falsification principle, formulated by the largest philosopher and methodologist of science of the XX century. K. Popper. In accordance with this principle, only fundamentally refutable (falsifiable) knowledge can be considered scientific. It has long been known that no amount of experimental evidence is sufficient to prove a theory. So, we can observe as many examples as we like, every minute confirming the law of universal gravitation. But only one example (for example, a stone that fell not on the ground, but flew away from the ground) is enough to recognize this law as false. Therefore, the scientist should direct all his efforts not to search for another experimental proof of the hypothesis or theory formulated by him, but to an attempt to refute his statement. Therefore, the critical desire to refute a scientific theory is the most effective way to confirm its scientificity and truth. A critical refutation of the conclusions and statements of science is not

It allows it to stagnate, is the most important source of its development, although it makes any scientific knowledge hypothetical, depriving it of completeness and absoluteness.

Only true science not afraid to make mistakes and admit their ownprevious conclusions are false. This is the strength of science, its difference from pseudoscience, which is devoid of this most important property. Therefore, if any concept, for all its scientific appearance, claims that it cannot be refuted, denies the very possibility of a different interpretation of any facts, then this indicates that we are faced not with science, but with pseudoscience.

1.4. Structure of scientific knowledge

The term "science" is usually understood as a special field of human activity, the main purpose of which is the development and theoretical systematization of objective knowledge about all aspects and areas of reality. With this understanding of the essence of science, it is a system, the diverse elements of which are interconnected by common philosophical and methodological foundations. The elements of the "science" system are various natural, social, humanitarian and technical scientific disciplines (individual sciences). Modern science covers more than 15 thousand disciplines, the number of professional scientists in the world has exceeded 5 million people. Therefore, science today has a very complex structure and organization, which can be considered in several aspects.

The structure of scientific knowledge in terms of orientation towards practical application

According to the orientation towards practical application, sciences are combined into two large groups: fundamental and applied.

Basic sciences- this is a system of knowledge about the most profound properties of objective reality, which does not have a pronounced practical orientation.

These sciences create theories that explain the foundations of human existence; the fundamental knowledge of these theories determines the peculiarities of a person's idea of the world and himself, i.e. are the basis for the scientific picture of the world. As a rule, fundamental research is carried out not because of external (social) needs, but because of internal (immanent) incentives. Therefore, for fun-

Damental sciences are characterized by axiological (value) neutrality. The discoveries and achievements of the fundamental sciences are decisive in the formation of the natural-scientific picture of the world, changing the paradigm of scientific thinking. In the fundamental sciences, basic models of cognition are developed, concepts, principles and laws that form the basis of applied sciences are revealed. The fundamental sciences include mathematics, natural sciences (astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, anthropology, etc.), social sciences (history, economics, sociology, philosophy, etc.), humanities (philology, psychology, cultural studies, etc.). .).

Applied Science are considered as a system of knowledge with a pronounced practical orientation.

Based on the results of fundamental research, they are guided by the solution of specific problems related to the interests of people. Applied sciences are ambivalent; depending on the scope of application, they can have both positive and negative effects on a person, so they are value-oriented. Applied sciences include technical disciplines, agronomy, medicine, pedagogy, etc.

The structure of scientific knowledge in terms of subject unity

Also, science should be considered in a meaningful aspect, from the point of view of subject unity. Since the world around us can be divided into three spheres - nature, society and man, the sciences are also divided into three groups: 1) natural science (the science of nature), 2) social science (the science of the types and forms of social life) and 3) humanitarian knowledge that studies man as a thinking being. Each of them, in turn, is a complex set of many independent sciences interacting with each other.